The greatly changed curriculum which Dartmouth has announced for next year shows that the New Hampshire institution has not been oblivious to the lessions of the war period. The great emergency demonstrated the value of the man who has made himself a specialist in any field of human knowledge. It proved that the man who knew one thing well was far more useful than the man who merely knew a little of everything. And it especially proved the usefulness of those who had obtained a thorough training in the sciences.

In the light of these . lessons the Dartmouth faculty has recast the requirements for graduation in a way which will command the approval of all progressive educators. It has agreed upon a program of study which will require every Dartmouth student to take during his first two years in college, a minimum of work in each of the great fields of knowledge, ancient and modern literature, philosophy, the natural sciences, mathematics, and the social sciences. Then, when the undergraduate has obtained this general and preliminary grounding, he will devote his main attention to some "major course" or field of specialization chosen by himself and this will occupy his last two years in college.

At the request of the war department all the colleges and universities of the country established last autumn a special course dealing with the problems and issues of the great conflict. At Dartmouth, owing to the admirable way in which this course was planned, it proved to be a decided success. In the new curriculum, accordingly, it has been decided to establish, on the same general model a course in "Problems of Citizenship" which will be given by the co-operative efforts of various professors drawn from the departments of history, economics and political science.

Taking the Dartmouth plan as a whole it involves no radical departure from sound theories of higher education. It gives new emphasis to that part of the instructional program which deals with matters of present day interest, but there is on relaxation of allegiance to the classics. The opportunity to study the humanities remains as broad as before.

The following appeared in the Lowell Courier-Citizen:

A course of evolution which appears in the revised curriculum of Dartmouth college, being henceforth obligatory upon candidates for both A.B. and B.S. degrees, will go far, in the case of at least one college, toward making every educated man familiar with the terms and conceptions of evolutionary science. The ignorance of many college graduates, even those of the past 25 years, to say nothing of the older ones whose courses were planned before the days of the elective system and of laboratory methods, of the great romance of scientific discovery, of the very names and achievements of the discoverers, is as abysmal as if the 19th century had never been. Men and women who teach, preach or write for publications make the most egregrious errors through never having grasped what natural selection means. Many of the "intellectuals" who persistently over-stress the possibilities of social reform do so because they never heard of Weissmann and de Vries and Gregor Mandel and cling to the scientifically exploded notion that characters acquired in the lifetime of an individual may be inherited. Even those who have had engineering training, and have done quaternions and worked out the most elaborate formulas of organic chemistry, have often had no general cultural course in science: they were not taught in the plastic years to relate their scientific method to all their thinking about human problems. Yet the history of the universe to youthful minds is quite understandable and fuller of fascination than most annals of monarchies and republics. It is evidently the Dartmouth purpose to expect that every freshman or sophomore will take an interest in the cosmos. He is to learn the essential truths, so far as these have been established, of the formation of the solar system and of the planet on which we live; of the conditions under which protoplasmic life first began to develop in the tepid seas and of the evolution of the species under universal laws the purpose of which we may not know but the workings of which have within a century become clear. Of the several changes lately made in the course at Hanover this seems to be the most significant and to be most absolutely justified by the progress of thought and investigation in the present century.

The following is quoted from the Harvard Alumni Bulletin:

During the last couple of months both Yale and Princeton have announced radical changes in their programs of undergraduate instruction. Now Dartmouth joins the list with the promulgation of a greatly changed curriculum, the essential features of which are printed in this issue of the Bulletin so that Harvard graduates may be kept informed concerning the general drift of educational policy at institutions other than their own. The Dartmouth plan has not been adopted hastily or without careful consideration of all the possibilities involved. It has been under discussion for more than a year and its detailed provisions bear the earmarks of prolonged scrutiny.

In its general outlines the program which Dartmouth has now adopted does not differ substantially from what which Harvard put into force seven or eight years ago. It is fundamentally a scheme of compulsory concentration and distribution, leaving to the student a relatively small number of free electives. But there is this important difference: the Dartmouth undergraduate will be held to a narrower range of subjects during the first two years of his college course, and is not expected to begin his concentration or specialization until the beginning of his junior year. As at Harvard, each student will be entirely free to select any subject (Latin, mathematics, history, philosophy, etc.) as his field of specialization; but the courses which make up each field will be definitely prescribed by the departments concerned.

A noteworthy feature of the Dartmouth scheme is the provision that every undergraduate must take a half course in Problems of Citizenship," which will be given jointly by the departments of history, economics, and political science, although one member of the faculty will be placed in general charge of it. Likewise, a course on "Evolution" will be given by a group of professors selected from the various scientific departments, and every undergraduate will be required to include it in his program of study. The idea is that every student, at an early stage in his college career, should be brought into contact with two great fields of human interest; namely, social relations and the natural sciences.

Perhaps the most significant thing about Dartmouth's new plan is its unconcealed reaction against the elective system. It indicates that the current is running strongly against the old practice of letting the undergraduate plan his own education by hit-or-miss methods. College faculties are every where trying to make up their minds as to the "minimum essentials" of a liberal education. And where they are able to reach a concensus on this matter, the tendency is to put the essentials in a prescribed list. It is not yet easy to say how far this drift is likely to carry us before it comes to an end; but there is no mistaking its strength at the present time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRESIDENT TO THE ALUMNI

May 1919 -

Article

ArticleBASEBALL

May 1919 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF TRUSTEES MEETING

May 1919 -

Article

ArticleTHE NEW CURRICULUM

May 1919 -

Article

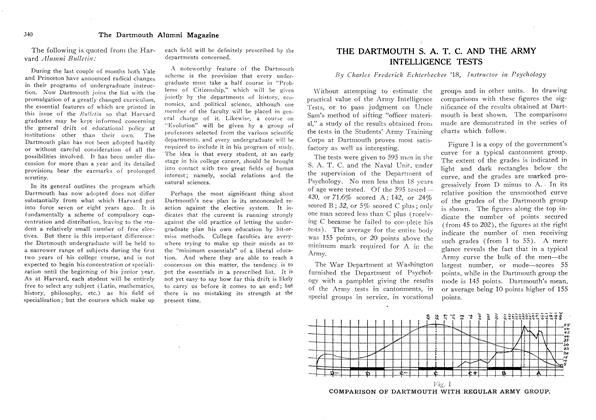

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH S. A. T. C. AND THE ARMY INTELLIGENCE TESTS

May 1919 By Charles Frederick Echterbecker '18 -

Article

ArticleCommencement is again upon us. It is always

May 1919