(This article is to some extent a composite of the speeches made by the President before the Alumni Associations during the winter and spring. The speeches were made, of course, without notes and the requirements of hardly any two occasions called for the same sort of an address, and yet in general, the theme was the same,—the discussion of relations between the alumni and the resident College in Hanover. These paragraphs are really the digest of the material from the contents of which the President took his subjects at the different meetings.)

A recent writer in the London Chronicle has said that we are at the present time in a situation analogous to that of travelers on a railroad train who find themselves unexpectedly approaching their distination, and who are under the immediate necessity of transferring their interest from the kaleidoscopic changes of the landscape, which has been flashing by, in order that they may focus their attention upon conditions of the platform, upon which they are to disembark.

I have somewhat such thought about the College in these times. The war period has been in education, as elsewhere, a period of never ceasing interest, and of constant changes, which we at Dartmouth believe on the whole have not been to any long time disadvantage of the College. The flexibility and the open-mindedness which have been essential to meet constantly varying circumstances will, we feel confident, be of permanent advantage in our consideration of educational problems with which the College has to do.

We have had the wonderfully complete revelation of the worth of the college undergraduate of the present day. We have seen that under the stress of a sufficient motive he arises to a seriousness of purpose and a self-forgetfulness of devotion to a degree that has not always been ascribed to him in times of lesser need.

The glories incidental to this fact attach themselves to the American college man as a type. We have no desire to differentiate the contribution made to the needs of the war by Dartmouth men from the contributions made by men of other colleges nor to make claims of special distinction for our men as compared with other men. The record of the American college as an institution in this period of crisis has been one in which we all alike can take pride. There is sufficient distinction in the assurance which we have that Dartmouth has proved worthy of the best in this great fellowship. We know of none whose accomplishment has been more wholehearted.

We pay special tribute to Dartmouth men tonight, not that they were braver than others, nor more enduring, nor even that they forswore all that they held dear more willingly than others, but because they did all of these things sufficiently and because they are our men, fresh in our memories and permanently established in our affections. To many of these, who have gone forth and will not return we pay the tribute of affectionate memory and high respect, while upon the strength of others we lean, as men certain to become the embodiment of supporting strength to the College in years to come.

Dartmouth in training for citizenship has met adequately her responsibility in war. Our solicitude must be to carry over a like sense of obligation and a like effectiveness of accomplishment to times of peace, so that among the routines and monotonies of daily life the influence of those qualities shall not be lost which have appeared so conspicuously under the stimulus of war. Our unceasing effort must be to capitalize our strength as effectively for the long pull as we did for the brief emergency. The function of education becomes again a general responsibilitiy instead of a specialized task. Again the College resumes its major motive of preparing for complete living, which Herbert Spencer said was the end of education.

It is an interesting coincidence, just at the moment when it had been foretold that all interest in liberal education would have disappeared and that the mind of the world would have turned exclusively to specialization and technical training, that the most conspicuous gift for education in recent years, if ever should have been announced, in the statement of the generous terms of Mrs. Sage's will, disposing of millions to colleges of liberal arts.

It is especially needful at such a time or us to examine anew the circumstances of our establishment and the obligations of our traditions and our opportunities, that we may have clearly defined the boundaries of the province Wit in which our activities can be of best avail.

In defining Dartmouth's purpose I always try to make it clear that we are not lacking in appreciation either of the large advantage or the great demand for such work as is being done by institutions of higher learning of other types. The world is a world of great necessities, and it requires many different forms of development of the mind. All that is being done in technical, industrial and vocational training is not only advantageous but necessary. But to only limited degree is this Dartmouth's work!

There is an interesting distinction that is suggested by dictionary definitions of the words "training" and "education." To educate is to develop mentally and morally; to train is to form by instruction. The differentiation between the two is one that must be kept clear in our thinking; for each has its vital place in the needs of the civilization of the day, but it is not at all the same place! The responsibility of the College is to educate, to develop mentally and morally, laying foundations deep and broad upon which the structure of life may be built. Changing the figure, the responsibility of the College is to develop intellectual self-command in the individual student, which in natural evolution may develop into intellectual mastery, through which he shall be enabled to dominate into external conditions of life with which he comes into contact, and thus to qualify for leadership.

There can be no question as to the insistence with which the worlds is going to call for men intellectually strong, in numbers never demanded before. The area of the world has become greatly restricted through the developments of science, because distance is not a matter of miles but a matter of transportation and inter-communication. The ends of the earth are no farther away than it takes to get to them or to talk with them. The problems of the next generation will be largely world problems.

All of the questions involved in these tremendous changes are in addition to the normal fact that the last few years have so changed the conditions of life, and the conceptions of thinking that, with all circumstances as they were, the contribution in accomplishment of anything to the world would have been incalculably more difficult in years to come, even, than it has been in years recently past.

An American writer and thinker has said that a large part of life for all of us consists in walking up the stairs which our forefathers have built for us. Many contribute nothing to building new. stairs; the greatest build only a few. Were this statement to be written today I feel sure that the author would say that, through one group of artisans or another, the stairs of life have been measurably heightened by the events of the great war; and the climbing the stairs already built for us must require ambition and intelligent effort as never before, among those who wish to work on the higher levels.

The leadership of the future ought to be contributed to in ever increasing proportions by the College; and it seems inevitable that it will be largely on the basis of the contribution of the individual colleges that these respectively will be judged worthy of varying degrees of public confidence and of public support.

The understanding of this function of the College is particularly essential on the part of the alumni body. Among the interests which make for college strength, a college can safely consider its alumni body in but one of two ways: either to cut entirely loose from it, and to disregard its opinions and ignore the possibilities inherent in its support; or else to insist that the interest of the alumni be constantly in the changing status of the college as a going concern. It is the latter alternative to which we hold at Dartmouth, in our relations to the alumni; and it is the attitude which we must insistently urge from year to year that the alumni adopt in regard to the operating college.

The cooperation of all the factors making for the present day Dartmouth is the essential reason that we are enabled to look with such satisfaction at Dartmouth's contribution to the needs of the time. Any attention which should be called to this would be incomplete without strongly emphasizing the team-play which has made it possible for the College to exert its strength as a unit. On the part of the alumni, there was the re-assuring demonstration of interest and endorsement which came from assuming the whole burden of the financial deficit of the last year. Moreover, the generous amount contributed was not more important than the considerable increase in the proportion of individual subscribers. On the part of the faculty, there was the desire and the determination to render effective service and to make individual accomplishments available for maximum advantage to the College work as a whole, the value and significance of which cannot be overstated. From friends of the College, even outside its formal alumni group, constantly there have come evidences of support that have added to the confidence with which those of us in Hanover could undertake our own special responsibilities. It is against such a substantial background that the view was set of the undergraduate seriousness and worth.

For the perpetuation of all this we must recognize the import of these ties, more closely knit than usual, and we must maintain the intimacies of contact and the interchange of points of view.

Alumni ask, again and again, whether there are ways, aside from financial aid, in which they can help the College. There are ways! Specifically, I wish to appeal for the bringing to bear of the great mass sentiment of the alumni at two points: first, they shall understand, appreciate and support the overwhelming importance to the College of a faculty of the first rank; second, that they shall exert their influence and show their solicitude for the intellectual ideals of the College to a degree that every undergraduate may feel the force of this influence, even as he feels the interest and concern of the alumni body in certain extra-curriculum activities.

I doubt very greatly if any proportion of the Dartmouth graduates understand the high place relatively which the departments of instruction at Dartmouth hold among educational institutions of the first rank throughout the country. I query if there is reasonably complete knowledge in any alumni group either in regard to the men of individual distinction or of the potentiality of the faculty collectively, as it is judged in scholastic circles.

Of course, to the extent to which such doubts are justified, things are not as they should be, for if the alumni are to have the voice in Dartmouth's affairs — which we are all agreed they ought to have—there is no one thing more vital than that they should understand the value and should show appreciation of the self-forgetful devotion and worth, individually and collectively, of that group on which the College must wholly depend for giving the inspiration for intellectual accomplishment, which is the main purpose of the College.

The trustees have taken vital action in determining that the main attention of the College during succeeding years shall be intensive development; that any available undesignated funds now in the treasury, and additional ones which may come to it for a time, shall be applied to upward revision of the salary scale until this is more commensurate with the value of the service which is being rendered by the instruction corps. Supplementing this, however, and not incommensurate in importance, there ought to be that added value of alumni apprepciation of the services of men who largely regardless of financial advantage or of gardless of financial advantage or of competing interests commit themselves to a life of service within the College. There is no one thing, I believe, which would be so likely to add to the enthusiasm and zest with which the College instructor would continue his work as the knowledge on his part that the alumni both knew his value and appreciated his service. And there are few of us in any walks of life who derive complete satisfaction from work which is neither understood nor appreciated.

The other point at which I wish particularly to urge the alumni cooperation is in bringing the effect of its great moral influence to bear upon the student body in support of the real standards of the College, which primarily must be standards of the intellect. It is difficult to overestimate what would be the benefit to the undergraduates, if groups of alumni with whom they came in contact allowed themselves to show the genuine interest in the intellectual standards of the undergraduate body which without question many of them feel. If they bespoke an anxiety that undergraduate interests should be of the widest possible sort, if they showed a desire that undergraduate thinking on any subject should be accurate, the influence of such an attitude as this would inevitably result in a toning up of all the standards of undergraduate life. It would further result in setting at work new influences which would bring to the College additional numbers of men of superior mental capacity, on whom the effect of the College education would be to train for the world's needs as these cannot be trained for now.

I wish further to emphasize a fact that I have been reiterating before all the alumni groups, and that is the danger that lies in the insufficiency in number and in size of scholarships at Dartmouth. We take great pride in the expansion of our geographical area, by which the undergraduate body represents in its proportions a national constituency unsurpassed at any other college. There is danger, however, that unless the scholarship conditions are revised,* our social area will become restricted, to the elimination of men of lesser financial means, with corresponding loss of that sturdy type from the farms of the hills and valleys of New England which formerly made up the strength of the College; while in the inaccessibility of the College to the sons of artisans and other workers we shall fail to represent sufficiently a cross section of the social state, which in my estimation, the undergraduate body ought to represent as completely as possible, if we are to preserve the spirit of Dartmouth traditions of democracy in the undergraduate body.

We have great pride in the completness of the College plant. None of us would willingly forgo the advantages that inhere in fireproof buildings and the painstaking type of housekeeping which makes Dartmouth so attractive as it is. But it is a fact that there is an expense involved in all of this such as did not exist with the inconveniences and the frugal comforts of the old-time college plant. Moreover, the cost of board and the general expense of living has so increased that there are no comparisons between the College expenses of the present day and those of even twenty-five years ago.

It is a conservative statement to say that a man requires fifty per cent, more than he required for his college course a quarter of a century ago. And to live in relationship with his fellows as men lived in the older days a man ought to have at least a hundred per cent more for his college course. Meanwhile, scholarship funds, which were at that time insufficient, have nowhere near proportionately increased in number for the college of 1500 over what were available for a college of 350; and the income of scholarship funds, due to shrinking interest rates, is, of course, less than in those days.

I think that there can be no question but that the first necessity for the College is to establish additional scholarships of three or four times the size of what we now have, placing thereon requirements for scholarship achievement which shall insure that these go only to those men who are willing to qualify on the basis of the standards of the College most to be desired. My conviction is that such an enlargement of individual scholarships, and such an increase in the number of scholarships, would counteract immediately the tendency to any restriction of the social area represented by the undergraduate body; and at the same time would make possible attendance at Dartmouth by an increased number of men of high scholastic achievement, who wish to attend Dartmouth, but who of necessity go to colleges where greater recognition is given in the way of self-help for men of mental potentiality.

It seems to me more clear the more the situation is studied, that Dartmouth's problem is in a large measure an individual one, and that she must blaze her own trails to a considerable extent. The question of what is or what is not done elsewhere may have little bearing upon what should be done in Hanover. The College is at once under particular obligations, and at the same time is singularly free, to be independent, because of its freedom from the hazards of insufficient numbers or of restricted spheres of influence. There is, for illustration, no single preparatory school which specializes in fitting men for Dartmouth, in contrast with the situation at many of the colleges, where classes in considerable proportions come from a group of a very few such schools. Moreover, at a time when men of the widest possible outlook upon life are being especially sought, it is interesting to reflect how little the spirit of provincialism is likely to obtain in a college whose area of undergraduate constituency is so large that fifty percent of it represents territory outside of New England boundaries.

Among educational institutions in such numbers, principally intent on being something besides colleges, Dartmouth with her widely distributed numerical strength, her wealth of honorable traditions and her strength of instruction corps is bound to be distinctive, specializing as she does on being a college. We must, therefore, accept nothing less than certainty that this distinction shall be safe-guarded as a distinction of excellence. Her separateness from responsibility to bulwark the strength of something else than the college, leaves her free to solve her own problems, as the college within the university can never be free to devote itself to its own interests. In large degree these latter aspire to strength as agents of the graduate schools, rather than as principals themselves, to the corresponding disadvantage of men to whom the college course is the final step in the educational process.

Lest this be thought an argument over emphasized by the college, I wish to quote direct from a spokesman for the university point of view. Professor Thorstein Veblen, in his recently published book on "The Higher Learning in America" in discussing this matter says: "The attempt to hold the college and the university together in bonds of ostensible solidarity is by no means an advisedly concerted adjustment to the needs of scholarship as they run today. By historical accident the older American universities have grown into being on the ground of an underlying college, and the external connection so inherited has not usually been severed; and by illadvised, or perhaps unadvised, imitation the younger universities have blundered into encumbering themselves with an undergraduate department to simulate this presumptively honourable pedigree, to the detriment both of the university and of the college so bound up with it. By this arrangement the college—undergraduate department—falls into the position of an appendage, a side issue, to be taken care of by afterthought on the part of a body of men whose chief legitimate interest runs—should run - on other things than the efficient management of such an undergraduate training-school,—provided always that they are a bona fide university faculty, and not a body of secondary-school teachers masquerading under the assumed name of a university."

Likewise, Professor Edwin R. A. Seligman, in an address at the opening of Columbia University in 1916, speaking upon the subject of "The Real University" said: "The internal perils I should characterize as the college and the professional school. The college is indeed a part of the university, but only in the sense of being a threshold to the university. * * * * The college which forms a part of the university must be radically different from the independent or small college. It can not remain alone and apart. It must not limit its horizon to the purely parochial view. If it is primarily the approach to the university, it must fit into the university structure and not be permitted to dominate that structure."

Recently a line from the Oedipus Rex was read to me, which might well serve as a text for most talks upon the College, "Good for naught is ship or state, empty, without strong men within". The strength which is demanded of men today is essentially the strength of intellect, and it is to the production of men of such strength, backed by strength of soul and health of body, that Dartmouth is pledging itself. To this pledge we urge the commitment of every individual alumnus, that the strong forces already at work shall receive that increment of added force which may thus become available, further insuring that Dartmouth's product shall be the man qualified to add to the fullness of life for others and to accept fullness of life for himself.

We do not want to produce one-sided men, for the cost in effectiveness is too great among such men, whatever the virtues of the attributes they have. It was Kant, I think, who gave a definition that it were well for us to accept today, that "idealism without practice is empty, while practice without idealism is blind.

Among the immediate functions of the colleges of liberal arts such as Dartmouth, it seems to me that four stand out particularly in these times: —

First, that they shall give as in the past, capacity for appreciation, but shall increasingly give, more than ever before, ideals of services; that is to say, altruism rather than a spirit of acquisitiveness should result from the influence of the college.

Second, that they shall recognize responsibility for character development as one of the first obligations. It has been demonstrated in the war that pure learning is unmoral, and is applicable alike for benefit or injury, except as learning is tempered by character.

Third, that education shall be safeguarded, to the end that it be absolutely untrammeled. Education in Germany, for illustration, became subservient to the state and was thereby polluted. For education to become the agent of any economic group or of any social class would be as dangerous.

Fourth, that the influence of education shall be made compensatory, offsetting on the one hand the inertia of conservatism and on the other hand restraining the excesses of radicalism, recognising meanwhile that of necessity this influence will tend toward what seems radical in any given age, if the college is to dwell with the leaders in the world of continuing evolution.

Phillips Brooks in his great sermon in Westminster Abbey declared "The challenge of nation to nation in all ages has been, show us your man". As truly that is the challenge of civilization to education and to the colleges; and their worth will be estimated upon the basis of the quality of the men they can show. The sum of all other obligations of the College seems to me to be Dartmouth's obligation to make sure of the heartiness with which she can welcome such a challenge either now or under the increasing demands of the future.

*The trustees have already made this revision. The details are given in the report of the trustees' meeting and elsewhere in this number.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

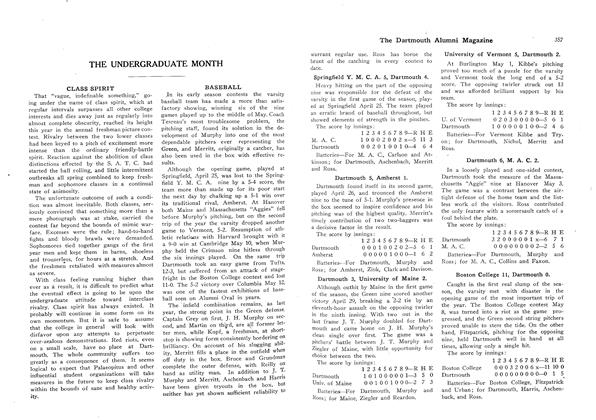

ArticleBASEBALL

May 1919 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH LEADS

May 1919 -

Article

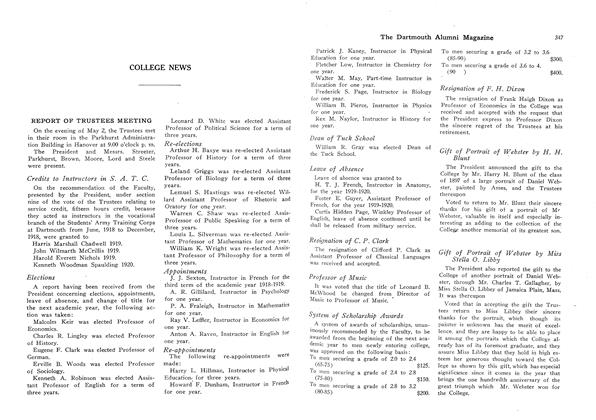

ArticleREPORT OF TRUSTEES MEETING

May 1919 -

Article

ArticleTHE NEW CURRICULUM

May 1919 -

Article

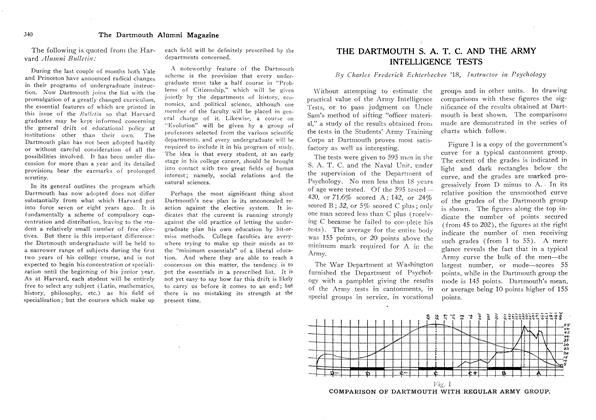

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH S. A. T. C. AND THE ARMY INTELLIGENCE TESTS

May 1919 By Charles Frederick Echterbecker '18 -

Article

ArticleCommencement is again upon us. It is always

May 1919