ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE, Shakespeare concluded after plotting the twists, turns, and intrigues of human life. But that was four centuries before game theory took center stage as a way of understanding the ins and outs of decision-making. Were the Bard alive today, he might well be penning: All the world's a game. For chances are good that as a modern chronicler of human interactions, Shakespeare would be a game theorist.

As such he would be keeping company with some of this century's most brilliant minds. John Von Neumannthe mathematician who fathered the computer and helped pioneer quantum physics coined the term game theory in the 1920s to describe the probability-based models of decision outcomes he was devising. In 1944 he and economist Osker Morgenstern published Theory ofGames and Economic Behavior, the book that gave the world its understanding of zero-sum games (in a limited pie, one person's loss is another's gain), and other strategic insights that had applications far beyond the world of theoretical math and even well beyond economics. From political science to biology, computer science to ethics, diplomacy to management, game theory has provided theoreticians and practitioners alike with models for interpreting complicated situations in which outcomes do not depend solely on one's own decisions. When the 1994 Nobel Prize for economics went to game theorists John Nash, John Harsanyi, and Reinhard Selten, the real surprise was not that game theory was being recognized but that the recognition had been so long in coming.

We asked economics professor and game theorist Sang-Seung Yi to explain how game theory is played.

First, some basics. A "game" is a decision-making situation in which one person's optimal decision depends on the decisions of other people and vice versa. "The most important assumption in game theory is that the decision-makers are rational that each player will try to make the best possible decision given the person's skills and the information each has about the situation," Yi explains. "The goal of game theory is to predict the strategic decisions rational players will make."

One of the examples Yi uses in class is the classic prisoner's dilemma:

Two prisoners, A and B, falsely accused of being co-conspirators, are locked up in separate cells. Each is told that the other is talking. Each prisoner knows the options: if each claims innocence, each will get three years of prison. If A confesses and implicates B (who is claiming innocence), A will get a one year sentence and B will get 25 years; the tables could also be turned, with B implicating A. If each prisoner confesses, each gets ten years.What to do?

As Yi explains, each prisoner knows that the other is either confessing or pleading innocent. If A confesses, B gets 25 years by pleading innocent and ten years by confessing, so it is better for B to confess. If A pleads inno cent, B gets three years by pleading innocent and only one by confessing; again it is better for him to confess. Prisoner A, meanwhile, is reaching the same conclusion for himself. Each prisoner confesses. Each gets ten years.

"A remarkable feature of this game is that each side tries to minimize his own prison time, and yet the outcome is jointly worse than if each had followed the strategy of maximizing his prison sentence," says Yi. "In general, pursuit of self interest can result in a jointly worse outcome because of the interdependence of decis ions."

Real life examples of the prisoner's dilemma can be seen in competition between firms, says Yi. "An industry has two firms, A and B. Each of them can charge a high price or a low price. If both choose high prices, each makes $3 million. With low prices, each makes only $2 million. But if one sets a high price and the other a low one, then the low-price firm makes $4 million and the high-price firm gets a mere $1 million. No matter what firm B does, firm A does better by charging a low price than a high price. The same holds for firm B. Thus, both firms choose low prices and earn only $2 million, although they would do better if both set high prices. The pursuit of selfinterest again results in a collectively undesirable outcome for the firms."

Another prediction in game theory, says Yi, is that even completely selfish decision-makers can cooperate with each other in a long term relationship. "Suppose that instead of playing the prisoner's dilemma game just once, A and B have to play it over and over again. By rewarding 'good behavior' (no confession by the other player) with no confession and by punishing 'bad behavior' (confession) with confession, the two players could eventually reach the jointly preferred outcome of no confession." Clearly, knowing game theory could save them a lot of trouble.

Still another insight from game theory centers on rationality, Yi says. "Not all decision makers are rational, and a rational decision-maker can turn this fact into an advantage by building up a reputation for making irrational decisions,' Yi explains. "Suppose that your firm is a market leader. You, the CEO of the company, are a rational decision maker, which in the business context means you want to maximize profit. Suppose that an upstart firm develops a substitute product. For short-term profits, it is best to accommodate the new competitor. But suppose that your firm is going to face a series of new entrants in the future. You may be able to build a reputation for being a tough competitor by aggressively fighting the new entrant through cutting your price significantly. You forego shortterm profits by doing so. But you may be able to persuade other potential entrants not to tangle with you, resulting in future profits that outweigh the short term losses from the price war."

Yi himself is using game theory to sort out the implications of trade agreements like NAFTA. Despite common wisdom that removing trade barriers increases trade, Yi outlines another scenario: If trading blocs turn protectionist against other countries, the size of the global pie may shrink. To assess such outcomesand the international institutions which lead to them—Yi is modeling countries as trading bloc decision makers, then letting them play out various global trade strategies.

So swat up on game theory. In the games of life, how you play really does count.

In the games of life,how you play ideallydoes count.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

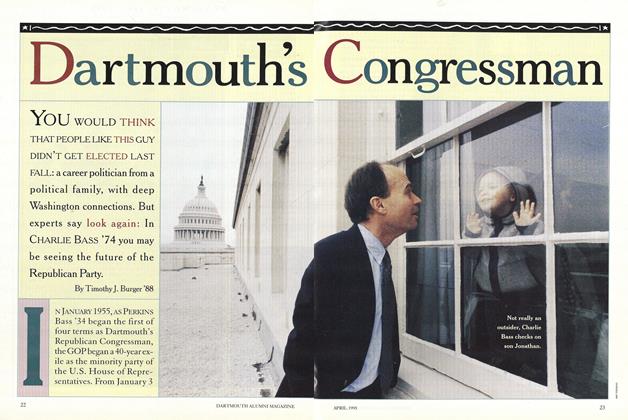

Cover StoryDartmouth's Congressman

April 1995 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Pull

April 1995 By Jay Paris -

Feature

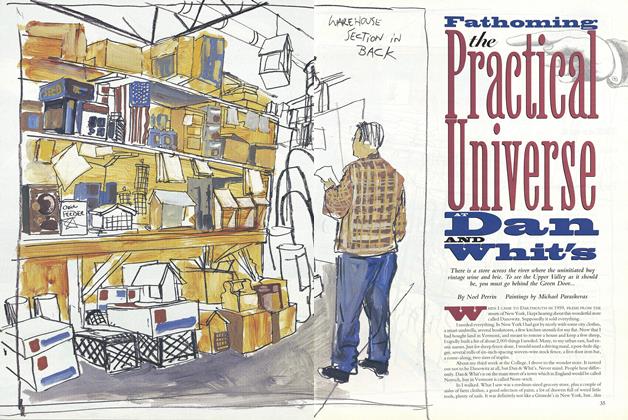

FeatureFathoming the Practical Universe Dan and Whit's

April 1995 By Noel Perrin -

Article

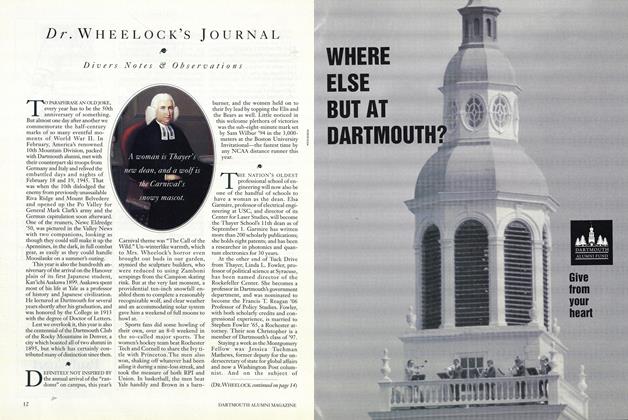

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

April 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1992

April 1995 By Jessie W. Levine -

Class Notes

Class Notes1991

April 1995 By Sue Shankman

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleA Professor's Delights

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSound Words

FEBRUARY 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

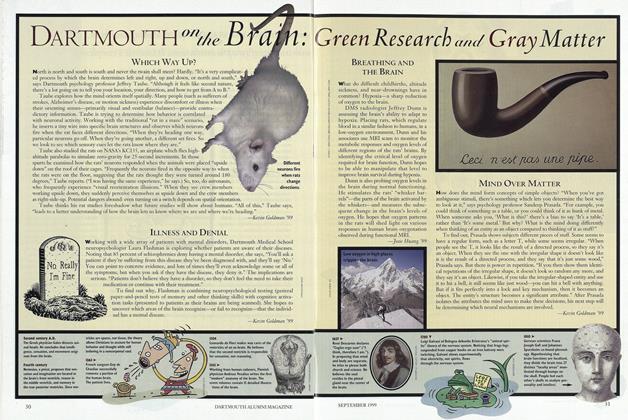

InterviewDartmouth on the Brain: Green Research and Gray Matter

SEPTEMBER 1999 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMPreparing for a Life in the Pits

Nov/Dec 2000 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleSEVERAL FRATERNITY HOUSES UNDER CONSTRUCTION

August, 1925 -

Article

ArticleVladin and '52 Friends

NOVEMBER • 1987 -

Article

ArticleGREEN JOTTINGS

MAY 1968 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

Nov/Dec 2005 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

ArticleMedical School

DECEMBER 1964 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M'27 -

Article

ArticleTribal Law

MARCH 1999 By SHIRLEY LIN '02