If one were to select from the alumni of Dartmouth the typical Dartmouth man, the one of us all who has manifested most fully all that the college has stood for and has stamped upon its men, one would pause long at the name of Thaddeus Stevens, 1814. If ever there was a son of the granite, as individual as the Vermont that bore him, uncompromisingly democratic, as free and freedomj-loving as the hill winds that rooted the Dartmouth pine, intolerant of oppression, a born leader of men, it was the great Dartmouth Commoner who in the most critical period the republic has ever known assumed the complete leadership of Congress and for a decade was a power in war and reconstruction second only to Lincoln himself. When he died in 1868 the caustic Godkin of the Nation, usually parsimonious of praise, could write what might have been used as the typical epitaph for a son of Dartmouth College: "His greatest value lay in his character as a man, and his eminence in that character nobody can deny. A manlier man never sat in the House. He had a conscience of his own, opinions of his own, and a will of his own, and he never flinched from the duty of asserting them."

It has been the glory of Dartmouth that she has molded her men very often from unpromising materials, and surely nothing could seem more unpromising than the crude northern Vermont boy who came to work his way through the college in 1811. His father, dissipated and worthless, had disappeared early, leaving the burden of a family of four boys upon the mother with no resources save a few ragged acres farmed against the protest of Nature herself. One of her boys, Thaddeus, because he was large and frail in body, unfit to wrestle for a living with Vermont rocks and polypod, she determined to send to college. No one but a Yankee woman would have thought of such a thing; no one but a Yankee woman would ever have accomplished it. Her years of self denial and terrible labor that he might have an education Thaddeus Stevens never forgot. Through all his speeches and letters and writings runs a thread of praise for this heroic mother, ending only in that paragraph in his final will in which he endowed a fund to be used by the sexton to plant roses and other cheerful flowers at each of the four corners of said grave every spring" and furthermore in which he added another endowment to the Baptist church of which she had been a faithful member, explaining it with the words: "I do this out of respect to the memory of my mother, to whom I owe whatever little prosperity I have had on earth, which, small as it is; I desire emphatically to acknowledge."

His fitting school and college career may be called typically a Dartmouth one, at least typical in the earlier years of Dartmouth. He taught school to supplement the funds earned by his mother, he lived with the strictest economy, and he made the most of his opportunities. James Parton, the biographer, has said that in his school days he was "a dreamer and a sentimentalist", and Congressman Kelley, in his eulogy of him, declared that though he was always the most practical of men, his "whole life was colored and influenced by a vision." That vision came to him in college: the richest gift that Dartmouth 'gives her sons she gave to him in full measure. He entered her halls a boy, he went out a man with a vision of what a man's work must be if he is to be worthy of his alma mater.

A year of school teaching in Vermont followed his graduation. Law was to be his profession: he read it every moment he could get free from the school duties that supplied the funds that he must have, and then—on what slender pivots our lives swing—he received a letter from his college friend, Samuel Mierrill, telling of a vacancy in a Pennsylvania school. The result was that at 23 Thaddeus Stevens left forever his native New England to become a leader in that Keystone state which now is proud of him as one of her most illustrious adopted sons. The school position which Merrill had secured for him was the assistant principalship of the York County Academy, York, Pennsylvania, under the direction of the Rev. Dr. Perkins. His year at York is still remembered, and the testimonies concerning him may be summed up in two words used by one who characterized him: "remarkably studious". In addition to his school duties he made such progress with his law readings that he made application to be admitted to the bar, but "not having read law, according to requirements, under the instructions of a person learned in the law," he was rejected. The State of Maryland, however, had no such restrictions, and as a result at the age of twenty-four, he opened a law office of his own at Gettysburg, the county seat of the recently organized Adams County, Pennsylvania, ten miles above the famous line separating the North from the South.

The life of Stevens from this point divides itself into four periods. For sixteen years, or until 1833, he was a country lawyer, struggling into prominence. Then at the age of forty-one he entered the state legislature and for seven years was one of the dominant forces in the government of the commonwealth. After leading the '"buckshot war," famous in local annals, he returned home to find himself through the inefficiency of his partner in the iron furnace investment which he had made in Adams County, financially involved to the extent of nearly a quarter of a million of dollars. Now opened the third period of his life. In 1842 at the age of fifty, he set about deliberately to free himself from this enormous indebtedness. Realizing that it could not be done by a country law practice, he removed to the city of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and soon was in charge of some of the most important cases of his time. In seven years he freed himself almost completely of his burden and in seven years more he was not only free, but again on the way to affluence. In 1848 and again in 1850 he allowed himself to be elected to Congress, but his heart was in his law practice, and when at the close of his second term he bade his associates in Washington farewell it was with finality. He was nearing sixty years of age, and there was nothing in a further congressional career to tempt him from his large and distinctive law practice. Then came the miracle of his last decade. In 1853, when he was but four years from the dead-line of seventy—an inspiration it is to all men who have reached the chloroform era—he was elected again to Congress, stepped quickly into a position of leadership, was made the chairman of the Committee of Ways and Means, and during the years of the war, and the reconstruction period that followed, was the dominating power in Congress, the man whose counsel ruled in every crisis and shaped more than did any other the movements of the war and the plans for reconstruction which followed. It is this last decade of his life that places him upon the roll of American statesmen. A recent biography devotes 124 pages to a record of his life until he was sixty-six and 486 to this last decade. Had he died at the age when most men consider that they have found their lifework and are rounding it rapidly to a close, he would be known today only in Pennsylvania, and there only because of a single deed in the Pennsylvania legislature and a brilliant career at the bar.

To study these four periods in Stevens' life is quickly to discover a remarkable fact: in whatever circle he entered quickly he became the leader and the dominating power. After his first law case as a callow practitioner, a case-that brought him a $1500 fee, he was the acknowledged leader of the Adams Countv bar; in the Pennsylvania legislature he became quickly not only the leader of the House but the power that with a single speech could compel both House and Senate to pass a bill that would have failed to pass without him and would have been defeated had it been submitted to the votes of the people of the State. As a law practitioner in Lancaster he arose at a bound to the leadership of the Pennsylvania bar, though at that time it contained some of the most brilliant barristers America has produced. During one session of the State Supreme Court Stevens handled not less than six of the cases that came before it. Of his dominating leadership in Congress during his last period it is needless to say more.

But it was not in Washington: it was in Harrisburg during his second period that Stevens made the effort that he styled "the crowning utility of his life." His adopted state honors him today fully as much for his part in her struggle for a free school system as for his brilliant later career in Congress. In 1834 "the rich" paid tuition for their children in the schools of the State, and those who could not afford the price were classed as "the poor" and schooled free. When it was proposed to extend to the whole State "the great democratic principle of free schools for all on equal terms", the thrifty Pennsylvania Germans arid others opposed it with vigor. They were willing to help educate the children of the poor, but why should they be taxed for the education of the children of the rich? The rural sections were unitedly against the proposal. Stevens had been elected by a constituency that to a man opposed it. The Senate voted decisively against the free school principle, and the majority of the House would have done the same, but before the vote was taken Thaddeus Stevens, the Vermonter, the son of Dartmouth College, the democrat, the product of free institutions, was allowed to speak. All the senators, knowing the calibre of the man, crowded into the legislative hall to hear him, and they heard one of the greatest speeches ever made on Pennsylvania soil. Says his biographer, McCall, it was a speech that ''produced an effect second to no speech ever uttered in an American legislative assembly." In defiance of the constituency that had elected him,, he pleaded for free schools of that New England type which had made his own career possible. With a sarcasm that was withering he termed the opposing bill "An act for branding and marking the poor, so that they may be known from the rich and the proud." He declared that the colleges of Pennsylvania were "languishing and sickly" with "scarce one-third as many collegiate students as cold, barren New England", and that the cause lay in her lack of free schools. That was the reason she was forced to import her leaders from other states, for "not to mention any of the living, it is well known that that architect of an immortal name, who 'plucked the lightning from heaven and the scepter from tyrants' was the child of free schools." Says Colonel John W. Forney, who heard it, "Never will the writer of these lines forget the effect of that surpassing effort. All the barriers of prejudice broke down before it. It reached men's hearts like the voice of inspiration. Those who were almost ready to take the life of Thaddeus Stevens a few weeks before were instantly converted into his admirers and friends. During its delivery in the hall of the House at Hiarrisburg the scene was one of dramatic interest and intensity. Thaddeus Stevens was then forty-three years of age and in the prime of life, and his classic countenance, noble voice, and cultivated style, added to the fact that he was speaking the holiest truths, and for the noblest of all human causes, created such a feeling among his fellowmembers that for once, at least, our State Legislature rose above all selfish feelings and responded to the instincts of a higher nature." The House passed the bill at once, and what is more remarkable, the senators, as soon' as they reached their chamber reversed almost unanimously their previous action. The governor thereupon signed the bill,, and since that day Pennsylvania has had free schools.

From 1860 to 1865 Thaddeus Stevens was the Clemenceau of America, the fiery voice of the Civil War, though he did his work not as premier but as leader of the people's branch of the legislature. As with the great Frenchman, from first to last his only cry was, "I wage war." "The only way to end this rebellion is to conquer the rebels" was the Scipio-like burden of his speeches. He was for no compromise, no half-way measures, no leniency, no quarter. Just as long as citizens were in arms against the government they must be fought with every force that the government could devise. From the first he was for emancipating the slaves and arming them against their masters: it would do justice to the negro and it would cripple the enemy. Day after day his scorching invective, running like fire over the House, burned out cowardice and wavering and self-seeking from a body not always to be relied upon as inflexible and incorruptible. Never for an instant did he hesitate or compromise, or lessen one jot the intensity of his convictions. Every man North and South knew precisely what he stood for, knew where to find him at every moment of the crisis, and knew to the full the strength of his inflexible soul. No man ever had more virulent enemies, and yet among all his enemies there was not one who did not in reality respect him. In America backbone is respected even by enemies and it was a saying of Chief Justice Chase that when Thaddeus Stevens left the House he took with him more backbone than he left.

Of the policies of Stevens, of the leadership that he gave to the vital Committee of Ways and Means, of his leading part in the impeachment proceedings against President Johnson, of his work during the reconstruction period, I may not treat: a volume could not do it justice. One phase of his work, however, stands out so prominently that to omit it would be to leave incomplete the picture of the man: his attitude toward the negro. Born in the freedom of a New England mountain village, educated in the democratic atmosphere of a New Hampshire college, molded by a social regime that was fundamentally and gen- uinely religious, he hated slavery with a hatred that was in reality a religion. With Whittier he could say, Mine is "A hate of tyranny intense And hearty in its vehemence, As if my brother's pain and sorrow were my own."

In everything that concerned the rights of the negro, that treated him as a man, that gave him the equality among men that he possessed before his God, Stevens went to the extreme. How deep were his convictions appears in his will in which he ordered that his body be buried in a small, obscure cemetery in Lancaster explaining his choice with a sentence which was to be placed upon his tombstone:

I repose in this quiet and secluded spot, Not from any natural preference for solitude, But finding other cemeteries limited by charter rules as to race, I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death The principles which I advocated through a long life, Equality of man before his creator."

No man; was ever more individual than Thaddeus Stevens. He imitated no one; he followed no one; he was from first to last completely himself, a unique and picturesque figure hard to parallel in American history, that repository of picturesque characters. He was never married : he lived his life surrounded by men in an atmosphere austerely and almost exclusively masculine. His memory was remarkable: he could go through a whole legal action for days without making a note and have at his tongue's end all that he needed in the final summary of the case. His quickness of mind .also was extraordinary. His caustic wit, his quaint turns of expression, his instant repartee were so fully appreciated that the galleries were always full when it was known that he was to make a speech. The journals of Congress when they contain his speeches are freely interlarded with "Laughter" and "Great Laughter". In his powers of invective and epigrammatic wit and scathing denunciation again he resembled Clemenceau. Few dared to interrupt him or to heckle him, but his interruptions of others were constant and always effective. For instance when an opponent, a nervous member of the House, paced constantly up and down the aisle as he spoke, Stevens interrupted the debate with, "Mr. Speaker: Does the gentleman expect to collect mileage for his speech?"

In the court room, in his treatment of witnesses and of opponents, his constant wit, and it was not always refined, enlivened the trial and often won the jury. Stories of his retorts and of his impaling thrusts at the opposition are still told in Pennsylvania court rooms. For instance, a judge who had been nettled by Stevens' running expressions of disgust at his rulings, finally ordered him to be careful or he would arraign him for manifesting contempt of court. "Manifesting contempt, your Honor!" retorted Stevens. "Sir, lam doing my very best to conceal it."

He was the constant and implacable opponent of Cameron, the political boss of the state, and when Lincoln was about to add him to his cabinet he protested with bitterness, calling him "the most consummate scoundrel in Pennsylvania." "You don't mean to say, Mr. Stevens," Lincoln broke in good naturedly, "that the man would steal, do you?" "Well," Stevens answered, "I do not think he would steal a red hot stove." This pleased Lincoln so much that he told it to Cameron who failed to see the joke and approached Stevens in a rage demanding that he retract his words before the President himself. "I'll do so," he said. Meeting Lincoln a few days later, Stevens retracted. "Mr. Lincoln," he said, "why did you tell Mr. Cameron what I said? He is very mad and made me promise to retract. I will now do so. I believe I told you that I didn't think he would steal a red hot stove. I now take that back." Such stories in great abundance enlivened Washington and the country for a decade. Says his biographer Woodburn: "The Stevens stories are innumerable, —perhaps about no other man in American history have more good stories been gathered." Most of them have been lost. There was no Boswell to gather them as they came spontaneously from him at the club or in the cloak room or in other gatherings of men, and they now live for a great part only in tradition.

A dramatic figure he was in a dramatic period, a Vermont-Pennsylvanian with a Dartmouth education, a fervent advocate of the common man, an apostle of democracy and individual liberty, a statesman unique among American statesmen inasmuch as he never held an office save as the people's representative in the popular body, state or national. Not only is Pennsylvania proud of him, but Vermont and the nation and the old college that sent him out with her stamp upon him. It is well that the rising generation in these days of shifting and self-seeking and hesitation study this sturdy commoner, this man of the granite, this product of Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

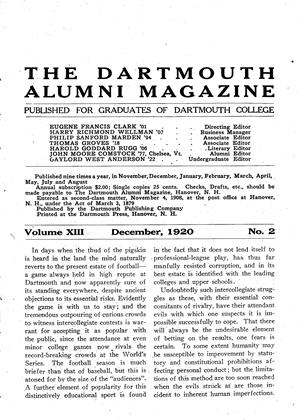

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

December 1920 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1920 -

Article

ArticleIn days when the thud of the pigskin

December 1920 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

December 1920 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

December 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleFALL MEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1920 By HOMER EATON KEYES