PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

December 1920 EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 December 1920

I

In January, 1904, two illustrated lectures were given by five of Hanover's long time citizens upon "Hanover Forty Years Ago". The room was crowded and the interest great. The lectures were afterwards printed in pamphlet form from shorthand notes and are a mine or perhaps better a potato patch of homely items from which every citizen might dig nourishment. But the pamphlet is out of print; college matters were not the primary object of the lectures; different people remember different things; some gleanings remain. And if excuse is needed for trying to take advantage of these facts, the sad knowledge of the passing of many of multiple memories and picturesque vocabularies without leaving any record is an incentive to lesser ones to do what they can or to try to do what they can't.

Mr. Charles P. Chase at the beginning of his dissertation upon the Migratory Houses of Hanover gives the experiences of a freshman entering college in 1865. In 1868 the experiences were much the same; but this freshman came from Chicago byway of Montreal and was aroused by the nuckles of a Pullman porter to crawl out upon the platform of the worst railroad junction at 3 A.M., about the same as now. The chill night air of September 3d struck into his unresisting form, but his principal reaction was the awe of the dweller in a flat country at the surrounding mountains. After five well-known hours of discomfort, an 8 o'clock train as now bore him to Hanover. The train facilities —if that is a proper term for them— differed little from those of the present time. A train sauntered southward about 11 A.M., and a mail train wandered in at any time after 2 P.M. It is also within memory that a train arrived from the south an hour or so after midnight. Unless he can prove an alibi on that particular morning, I shall assert that Ira B. Allen himself met me with a Concord-coach and drove me up that most discouraging hill and set me down hungry and homesick near the old Dartmouth Hotel. Later I may make remarks upon this institution, as I think my wife and I are the only survivors now of two years of its hospitality for room and board.

Ira Allen and his wife I knew better later when he had a baked apple face and was rather poddy. Mrs. Allen's voice I often heard regulating affairs at the stable, but she was a good woman and many are the times, in the days of much use of the extraordinarily cheap stable, when, as I paid my little livery bill, she would slip me back 50c or so with the statement that the remainder of the cash was plenty. Ira was inclined to somnolence in his later days, but was capable of peppery language on occasion. One of the utterances upon which rested his reputation as a local humorist was when good Dr. Leeds sought to bring him, into the fold and make him a regular attendant at the meeting-house; "Well, Doctor", he said, "if I'm not there don't you wait, but go right ahead with the services". And speaking of Dr. Leeds and the former blank white rear wall of the church, Mrs. Susan Brown, who was not one to speak lightly of the minister, said that when he was in the pulpit he looked like a fly in a pan of milk.

After refreshment a cousin who had one year's advantage of me took me in charge and I did those things which were becoming to a freshman, visiting those kindly Profs, in their studies, and passing all my examinations, some of them by answering inquiries concerning my father's health and if I hadn't come a good way to go to college. However, I was prepared to enter, so what difference did it make?

This was fifty-two years ago. Compare the College now and1 then by means of cold facts, the reader furnishing the other side of the parallel column. The total enrollment of the College that fall was 370. Fifty-three were from without New England, and of the remainder more than half were from New Hampshire. The list of all the faculty including non-resident medical lecturers was 28, of whom one, the Dean Emeritus, now survives. The "Academic" faculty numbered 14, with the addition of one non-resident lecturer. There were 261 "Academics". The catalog of the time gives Departments,—Medical, Academic, Chandler Scientific, Agricultural. These were all distinct and separate in instruction and administration. The Agricultural Department was the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts with a separate Board of Trustees. It had just started up with a Junior class of 10 but no faculty of its own. The Thayer School had been founded but not yet put in operation.

The buildings were the old row, Wentworth, Dartmouth, Thornton and Reed, the Observatory and the Chandler Building, with the gymnasium (now the home of the Thayer School) which had been in use something over a year.

Under the name of South Hall the College offered the Old Hotel (where is now the Currier Block) to "indigent" Freshmen, at $7.50 a year for each one of two in a room. Although the accommodations were as indigent as their occupants, life in the old barrack had many joys.

There were no "snap" electives because there were no electives of any kind. Every one in the Academic Department studied the same things if he studied at all. And if sitting beside the same men for four years and unitedly learning how each professor manipulated his cards and applied the marking scale had its disadvantages it also had advantages which will never come again. That scale was a wonder: 1 was perfect; 5 was absolute zero; and as it was worked the average marks of the first third of the class seldom got any nearer 5 than 1.30. Greek appeared as mental pabulum in nine of the 12 terms, and Latin in 8, and what was the matter with the other 3 or 4 terms I can not tell. The Calculus, differential and integral, was required, and imagination supplies the sequel. A year or two later a faculty who evidently could not live up to their stern responsibilities made a course in French "optional" with the Calculus.

The college modernist will be surprised, perhaps incredulous, when I tell him that among the early exhibits to the freshmen were the "class leaders" (in scholarship) . There would be little appreciation today of the joke much enjoyed around the College, that when old Spuds was asked by Professor Parker what "ambrosia" meant, he replied "the hair oil of the gods"; nor that Percy was called "Spondee" because he had long feet. The constant use of a word with so definite a technical meaning as "alibi" for "excuse" would have jarred many of us, and even now some of us object to the recurrent journalistic use of "aphasia" as loss of memory.

The United Fraternity, known as Fraters, and the Social Friends were still active organizations, and all freshmen were assigned to one or the other by alphabetical alternation. Thus they kicked football upon the Campus to avoid the excessive tension of the Old Division (often called Whole Division) game, which was Seniors and Sophomores vs. Juniors and Freshmen. These societies possessed libraries of nearly 9000 volumes each and gave occasion for lively politics since the librarians were elected, drew salaries and appointed assistants. They united in an "Exhibition" just before Thanksgiving at which our most talented seniors showed the world what real poems and orations were.

There was also an official "Junior Exhibition" in April at which the smart lads of the clasp spoke pieces. This festival was made the occasion of the distribution of mock programs supposed to be the work of Sophomores, who were, however, aided and abetted by the Seniors. These were usually of an indelicate, coarse, smutty, foetid, pornographic nature, if you know what I mean. And as detection of the author meant immediate extinction so far as college was concerned, they were printed and circulated in deepest secrecy. The most decent, I remember, announced that the procession would be headed by President Smith riding on a cow, and that he could be distinguished from the cow by his spectacles. That so kindly a gentleman as President Smith should be thus derided merely illustrates the extent to which an alleged joke sometimes befogs the youthful mind. I confess that I have a number of these programs carefully put away. Some remain from the distributions of half a century ago and some have been sent me by friends who doubtless feared to be caught with the goods upon them. As peculiar historical docivments I have hated to destroy them; but having confessed so much I will further affirm that I never saw any of them until they had been printed and circulated.

The College library then numbered about 17,000 volumes and was as carefully guarded as the United States Mint.

Perhaps I can avoid the usual class egotism by mentioning only a few items of college life and those either obsolete now or unusual at the time.

In the early days of the term we Freshmen were' notified1 to be on hand at a "Shirt-tail" to be held some time after the witching hour of midnight. The custom has survived in a form as attenuated as is the length of pajama jackets to that of the ancient garment. A distinguished New York doctor and I, with Freshman simplicity, prepared our lessons together for the following day (Lectures in those days were few, and we recited) with full intention of being among those present, but the sandman overpowered our youthful eyes and we went off to our beds. The affair was highly obnoxious to the faculty since it developed into a tin-horn serenade of a professor who had been married during the summer—the only case of the kind I have known in the College. Missiles were flung and bad language used, as the mob spirit prevailed. It happened that a member of our class beating a drum in the front of the array was recognized and promptly "rusticated", that is exiled to a selected place and tutor. The tutor in these cases was usually a country minister, and the exile was not so forlorn. For the remainder of his course his name was "Rusty". Fortunately neither his character nor his reputation were damaged by this misadventure. I think .he was the only victim of justice, which was considered a huge joke around college; but I suppose a great deal of college discipline has to go this way.

The fraternity question was quickly and easily settled. They held "menageries" in those days, which were more like the after-meetings of a revival season than anything else. The fraternities were Psi Upsilon, Kappa Kappa Kappa, Alpha Delta Phi, and Delta Kappa Epsilon. A little group who were in some way overlooked established Theta Delta Chi, so that all the class were gathered in, except two or three who stayed out for religious or economic reasons. Another fraternity was established a little later and the Aegis wisely remarked that the College now had all that it could support.

These were the days when flourished the Freshman societies, Kappa Sigma Epsilon and Delta Kappa. With our eyes tightly bandaged and in lock-step we marched into the hall of torture. The attendant demons who had been in college a year longer greeted us with dreadful moans and howls in sepulcral—l suppose sepulcral—voices and occasional articulate warnings like "Freshman bewaaaare." I had been bidden by friendly Sophomores to be of good heart as my body would not be mutilated beyond recognition. As a matter of fact most of us were not mussed up at all, though we had to place our hands on an iron mitt, which might have been red-hot but was not, to take the dreadful Path. A few lewd fellows of the baser sort having their victims blindfold and helpless took the opportunity to imbed pins deeply in the well-cushioned parts of certain freshmen who had been blacklisted as too blatant, and to administer sly pinches, and upon one they poured water through a dirty stove-pipe, but there was little ingenuity of torture in the proceedings. These societies maintained debates and other literary exercises for a part of the year, and initiation into the fraternities took place a short time before Commencement.

In the fall too we had a bad: example set us by a rebellion in '69, the senior class. Two of that class were suspended for an affair that does not seem at the present time a capital offense; and at the 11 o'clock recitation hour the class assembled in front of the Old Chapel with carriage and music and escorted the exiles to the station. According to my recollection,, Harry Smith son of the President, who was in a difficult relation, and another of marked and independent disposition attended the recitation, noble but lonesome. Then followed suspension of all the truants, great excitement, mass meetings in which eloquence was unsuccessfully used to persuade the whole college to join in a sympathetic strike, the resolution of the whole senior class to shake off the dust, letters from parents, sober second thoughts, then gradual, later rapid return of the whole class in apologetic mood to their duties. This might open a discussion of college discipline, but will not. It may be observed that some disciplinary actions are inevitable and indisputable, while others, from the point of view of twenty-one, are open to argument and must not be executed summarily.

I forbear to tell how Worthen, later called Tute, carried a cane to chapel and on demand properly surrendered it to President Smith, or of the gigantic struggles with '71, because such matters are in some form a precious remembrance of all classes and a bore to all the others.

In this sketch which is static rather than progressive, a cross section rather than a panorama, I can give an exact view of our athletics at the time.

There were legends of rowing, rumors of rowing to come, but the second advent of rowing really occurred about five years later. Paddling on the river there was, for canoes had been invented some years earlier.

Intercollegiate baseball was a feeble plant and the games were few and casual. A little rudimentary Egis for 25 cents announces editorially in what was thought to be a tone of discouragement and bitterness. "For sale, nine gray uniforms. The owners are sold already". But it was a grand era for the intramural game; five and even six games often raged at once upon the campus and that same Egis and others enrolled ten or twelve organized "nines" of one kind and another besides those that merely played and howled.

At that time the pitcher was restricted to a straight arm underhand pitch, but he was only 45 feet from the batter and was allowed nine balls. Runners were not allowed to over run Ist base; fouls counted for nothing unless they were caught in the air or on the first bound. Only babies wore gloves: that is, they were not worn. Catchers had neither mask nor chest protector. The catcher played up to the bat after the second strike or, if he was pretty nervy, when there was a runner on the bases. Every catcher received one or more foul tips on his features during the season. I have a photograph now of my class nine in which the catcher exposes; his profile in order to conceal a scrambled eye. As the ball was hard and lively and hit with all the violence of strong men, baseball was somewhat more an heroic adventure than at present.

Football was simplicity itself. You ran all over the campus, and when, as, and if you got a chance you kicked a round rubber ball to the east or to the west. .You might run all the afternoon and not get your toe upon the ball, but you could not deny that you had had a fair chance, and the exercise wasi yours and could be valued by the number of hot rolls consumed at the evening meal. The game was played by two or by two hundred. You always knew in which direction to kick because you were bound to know whether you were a Frater or a Social. The game could be played for half an hour or all the afternoon; some dropped out, others dropped in. It was especially adapted to the half hour between 12 when recitations closed and 12.30 when the dinner bell rang. It was glorious for exercise and had enough excitement to make it highly interesting. It gave ample opportunity for competitions in speed, finesse, dodging, endurance, and occasional personal collisions. For a year the faculty in its inscrutable wisdom debarred this highly useful game because of abuses, as they thought, in the manner of playing it. In my junior year I. was one of a committee sent by the College to ask the President please couldn't we play the game again if we would be good; and he, after taking counsel, said yes.

Croquet affected by seniors in their last term was regarded as effeminate, but from the language occasionally overheard it may have been a virile game after all.

There was always walking, and plenty of it.

For most the winter was a rather close season. Instead of the toboggan the snowshoe and the ski, the "double runner" dashed down the hilly roads which lead outward from the village in each direction. I suspect that coasting on the roads was unlawful, but it was done ; and there was nothing tame about it in going down nor easy about it in going up. The writer has done all the hills including Balch's, though part of that was rolling.

Hockey was played when there was good ice upon the river, but under the name of "shinney". There was no pond where is now "Faculty pond" or "Occom pond". Many years ago a pond must have been there, but it had become undamned. The present pond was recovered by a dam thrown across in 1899.

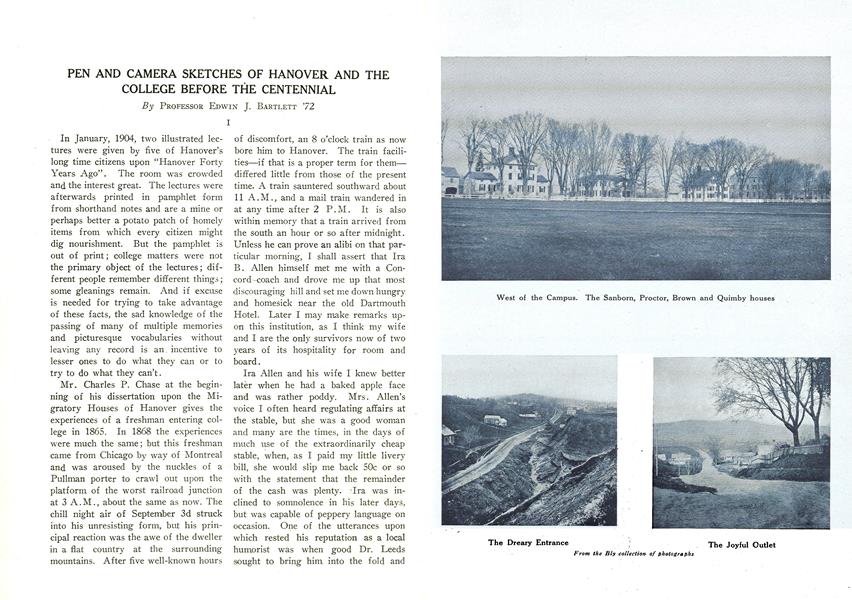

West of the Campus. The Sanborn, Proctor, Brown and Quimby houses

The Dreary Entrance

The Joyful Outlet

The Old Pine from the Church Steeple

South Hall, the home of eleven '72 Freshmen

The Crew

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHADDEUS STEVENS

December 1920 By FRED LEWIS PATTEE '88 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1920 -

Article

ArticleIn days when the thud of the pigskin

December 1920 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

December 1920 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

December 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleFALL MEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1920 By HOMER EATON KEYES

EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72

-

Article

ArticleATHLETIC SPORTS AT DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1905 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

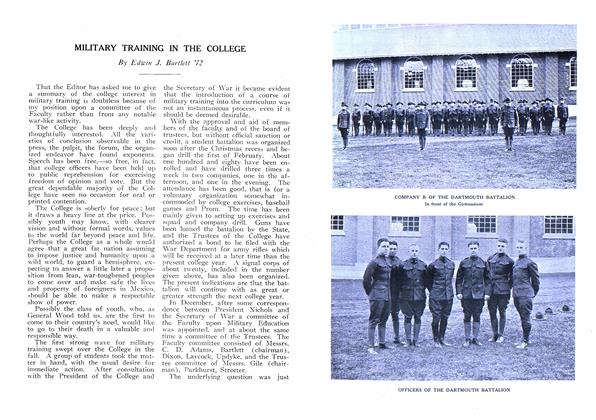

ArticleMILITARY TRAINING IN THE COLLEGE

June 1916 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

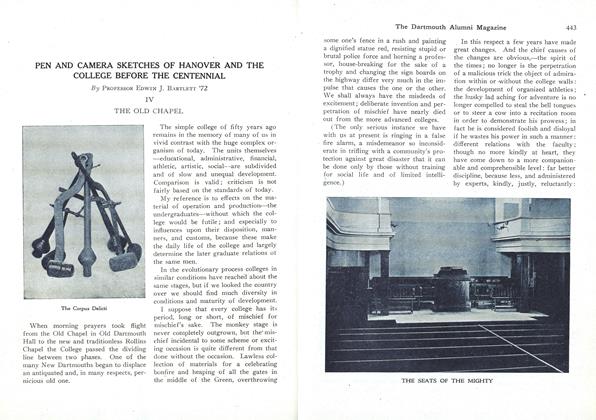

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

May 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August, 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72