is heard in the land the mind naturally reverts to the present estate of football- a game always held in high repute at Dartmouth and now apparently sure of its standing everywhere, despite ancient objections to its essential risks. Evidently the game is with us to stay; and the tremendous outpouring of curious crowds to witness intercollegiate contests is warrant for accepting it as popular with the public, since the attendance at even minor college games now rivals the record-breaking crowds at the World's Series. The football season is much briefer than that of baseball, but this is atoned for by the size of the "audiences". A further element of popularity for this distinctively educational sport is found in the fact that it does not lend itself to professional-league play, has thus far manfully resisted corruption, arid in its best estate is identified with the leading colleges and upper schools.

Undoubtedly such intercollegiate struggles as these, with their essential concomitants of rivalry, have their attendant evils with which one suspects it is impossible successfully to cope; That there will always be the undesirable element of betting on the results, one fears is certain. To some extent humanity may be susceptible to improvement by statutory and constitutional prohibitions affecting personal conduct; but the limitations of this method are too soon reached when the evils struck at are those incident to inherent human imperfections. From the beginning of time—and so far as appears the same will be true to time's last recorded syllable—mankind manifests the wagering propensity. That propensity's obvious unworthiness appears to make no difference whatsoever in any stratum of society. Deplore it as one may, the practical difficulty of eliminating it may as well be recognized at once and the situation envisaged as it actually is. So long as men are men they will continue to bet, whether it be on the results of games, races, elections, the fall of cards, or the trend of shares. Offensive publicity in the processt may be prevented; but beyond that one fears it is humanly impossible to go.

That constantly swinging pendulum, the chinning system, seems once more to be at one end of its arc by reason of the agreement to make the pledging of fraternity candidates a matter of postponement until the second semester of the freshman year. It seems unlikely that the college will ever go the full length of making membership in a fraternity coterminous with the last three years i.e., postponing the pledging of candidates until freshman year is virtually over- although this postponement would have much of good sense behind it. Surely a man would be better estimated after a year's acquaintance, and so would a fraternity. But the hardship of depriving the freshman of a whole year of fraternity life—one of the really joyous and worth-while concomitants of a college course—is apparent; and it is further to be remembered that even without length of acquaintance the fraternities have always managed to do themselves fairly well in the matter of eligible members. Putting off the "chinning" until the second semester is a plausible splitting of the difference between pledging men on the train down around Lebanon or Windsor, as used to be done by astute scouts, and pledging them only at Commencement. Whether it will be more nearly permanent and satisfactory than previous inter fraternity agreements remains to be determined by that inexorable arbiter, Time.

Fraternities of the present number, and of course the number has greatly augmented since the college first began to grow, probably do not take care of all the eligible material. In other words, the number of "oudens", once almost negligible, must now be very large. If there was any invidious feeling as to "oudens" it has probably disappeared; but as a matter of fact those of us who are as Bostonians would say, "between 35 years of age" cannot recall that there ever was anything invidious in it. Nevertheless the fraternity life is one of the dearest delights in a collegiate memory; and while easily susceptible of being overdone, it is, in its appropriate degree, an experience as valuable as any to be had in the classroom.

To an alumnus not on the ground, present chinning customs and the awesome ceremony of initiation remain unfamiliar. One recalls the elder days when a new man on the campus spent his first two weeks in the all but continuous consumption of grapes at evening gatherings, held in the various fraternity rooms—houses in those days were only a pious aspiration—and in listening to the merits of rival claimants for one's hand and heart. A popular man, or one known by his antecedents, would be dated up like a debutante for five nights ahead with parties to attend. The repetition of an invitation to come and eat more grapes was tantamount to a declaration of love—capable of almost infinite renewals if the prospective pledgee held coyly aloof; although toward the end one was usually bidden to speak up if one desired to retain this evanescent favor. The net result was that one in those days was prone to marry in haste and it was a frank lottery on both sides. The fraternities got a dozen to fifteen freshmen, almost sight-unseen; and the freshmen were tied up for the rest of their natural lives to associates whom they had no advance opportunities of knowing. Yet it worked reasonably well. It probably would work as reasonably well today, if the college were what it was then—a small college, in which the total membership (including the raucous and notoriously jovial medics) was less than 400.

As it is now, no doubt much is gained by allowing the proselyte to live undisturbed through at least one term, observed himself and himself observing. Putting off the ultimate decision until sophomore year would no doubt have the dire effect of producing a crop of purely freshman societies—a sort of trial-marriage system not lightly to be entered into. On the whole, one suspects that the second-semester agreement will serve best of all—yet one imagines that it, like so many previous agreement will be tired of in time. The obvious danger may well lie in the possibilities of technical evasion —surely a thing to be guarded against as unworthy of the traditions of the college itself, and of the fraternities now represented on the ground. Dartmouth custom has managed, we believe, to avoid the undue segregations and classifications to which life in overdeveloped fraternity establishments is prone. The just balance between fraternity pride and fraternity snobbishness is sometimes a difficult one to strike; and yet in the interests of democracy it is necessary to be struck. Thus far there has been no indication that at Dartmouth the college feeling is subordinated to fraternity spirit—but that, .of course, is hardly probable anywhere. The greater danger lies in the substitution of clubdom for college life—a narrowing of the daily social intercourse to one's housemates!—which may be, and is, partially guarded against by the prohibition of fraternity-house boarding. Like every other good thing,- fraternities are made to be used and not abused. A few in every college will abuse them—and will by so doing miss the best of fraternity life.

Alumni may be pardoned for a reminiscent amusement at the long forgotten feeling of fraternal bondsmen—for it will probably be found, by generations yet to be, that things change in proportion as one grows older. Note the awkward efforts of stiff-fingered old gentlemen of 40 to twist their hands to the requirements of the grip! Hear the quaint pronunciation of mystic words in Greek a language not so commonly spoken with ease and fluency by sophomores and juniors now as it was a generation back. But it remains an undying truth that, once a fraternity man, always a fraternity man. There is always the glow of pride upon discovering that the old society is still managing to secure a 'delegation creditable to its best traditions. And that supreme test—the readiness of the 30-year-alumnus to give of his substance toward purchasing a new tall clock or a new billiard table—is, no doubt, satisfactorily met by those to whom it is applied.

In the hands of Dartmouth's fra- ternities rests a large share of responsibility for the continued excellence and prosperity of the College, and above all for the preservation of that cherished thing which we call so vaguely, yet so definitely, the Dartmouth spirit. The manner of pledging new members is a mere detail, varying with the taste and exigency of the times. The life of a fraternity man varies not so far as concerns its duty to be a life of service of the college and its spirit, first, foremost and forever.

A wise precaution has no doubt been taken by the trustees of the college in requiring that before fraternities may erect houses for fraternity use in Hanover both the site and the plans for such houses must be submitted to the board of trustees for their approval. The reasons are obvious, and beyond doubt will command fraternity cooperation. It is an attempt to prevent unwise extravagance in the erection of club houses and thus restrain what might easily become a spirit of emulation, or of rivalry not altogether consistent with the democratic tradition of the college. Dormitories erected by the College itself, while certainly more pretentious than they were in the older days, have most successfully avoided the undesirable extremes of luxury and costliness which would easily conduce to the creation of invidious distinctions —and it is altogether fitting that fraternities be held to the same general principles of simplicity in the provision of their quarters.

Those of us who recall the day when Hanover boasted but one fraternity house that claimed to have a bathroom (and that a decidedly uninviting bathroom) were wont at the time to read extraordinary virtues into the rude conditions of the northern frontier. Sometimes it is feared we did protest almost too much as to the virile qualities promoted by primitive housing; and presumably very few surviviors of that Spartan period would deplore the growth in comfort manifested by the modern college dormitory. Nevertheless there was some fruit of sense beneath, and the safeguarding of whatever was virtuous in the lack of sybaritic environment is worthy to be undertaken. There seems to be no danger that Dartmouth will be wrecked on the "Gold Coast"; but it is well that the channel be plainly marked between the Scylla of luxury and the Charybdis of primitive discomfort.

It appears that one of the required courses in freshman year is one in applied gastronomies, as conducted in the college Commons. Under the rules every freshman not specifically excused by the Dean for good and sufficient reasons, must board, as Oxford would put it, "in hall". That it is an excellent and salutary provision can hardly be doubted. The board, overseen by the college, may be depended upon to be sufficient and wholesome—and is apparently as economically administered as board can well be in these days of inflated prices.

One dislikes to be forever shifting into the lean and slipper'd pantaloon, but the mind goes back to the day not so remote when there was not that convenient place of assemblage and sustenance which is denominated the Commons, with its abundant cheer, its semblance of clubdom and its officially certified provender. Freshman and all other classes made shift for themselves as best they could in a score of more or less rapacious private boarding clubs scattered over the town. The prices varied with the lack of excellence of the table and it was possible for one who valued his pocket more than his digestion to obtain what passed as daily bread for comparatively little money. Generally a man who served through his four years sampled at least half a dozen of these village resorts —and in all human probability many do so still, although it is safe to guess that the standard is higher than it was a quarter-century ago.

Announcements incident to this requirement of freshman year include one that a selected orchestra of five pieces will play during luncheon (otherwise in the circulars referred to as "dinner") and that its repertoire will include a sufficiency of classical works as well as the jazz so dear to the rising generations. Considering the din of 550 freshmen at dinner, jazz seems on the whole more likely to make itself felt by the assembled multitude than would the soft breathings of.Schubert; and yet one cannot but feel that if music is to be played at all in such circumstances it should be moderately heedful of what is best. Whether or not one does well to eat to a musical accompaniment is a moot question both in college and out. There appears to be a tradition in most eligible hotels and cafes that it is impossible to enjoy a public meal without an attendant orchestra, which in most such resorts drowns conversation. In the Commons, however, one inclines to lay one's sesterces on the diners for superior powers of assault on the auditory nerve.

The national and state elections, so recently in the thoughts of every one, had a distinctly Dartmouth tinge in this locality, Dartmouth men being chosen to be governors in New Hampshire and Massachusetts and Hon. Sherman E. Burroughs ('94) being handsomely reelected by his constituency in the Granite State.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHADDEUS STEVENS

December 1920 By FRED LEWIS PATTEE '88 -

Article

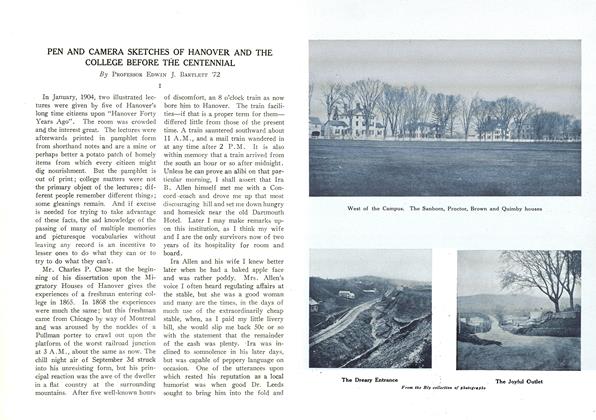

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

December 1920 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

December 1920 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1912

December 1920 By Conrad E. Snow -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

December 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleFALL MEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

December 1920 By HOMER EATON KEYES