Professor of English, Pennsylvania State College

One whose studies, as mine so often do, lead into old magazines and newspapers and century-old volumes, happens often upon unusual bits of Dartmouth history, amusing sometimes and sometimes startling. I have jotted down many of them from time to time, and reviewing them the other day, there came strongly upon me the conviction that not only has Dartmouth had the most picturesque history of all the colleges but that she has produced more picturesquely individualized alumni than has any other college. And peculiarly picturesque was that colorful fin de siecle era of the eighteenth century that lasted well into the first decade of the nineteenth, which may be called the golden era of the second Wheelock, the calm before the storm began to gather which so nearly swept away the old original Dartmouth. Only sketchily has its history been outlined. Sometime it will be written up realistically from its human side, dwelling upon its unique personalities, and the book will read like a romance.

Strahge personalities indeed came from this primitive Dartmouth. For a single instance consider the Reverend Solomon Spaulding. How many of the alumni associate Dartmouth with the founding of the Mormon church? I got a real thrill one day while turning the pages of a book remote indeed from the old college,—Alfred Criegh's "History of Washington County, Pennsylvania." The subject was that most romantic of old Pennsylvania towns. Amity (read its history sometime) and right in the midst of this history stood Solomon Spaulding, "a Connecticut Yankee, who had been graduated from Dartmouth College in 1785 and who wrote the first draught of the celebrated Book of Mormon." I got out my pencil and this was my jotting:

"He wrote a romance which purported to be translated from curious inscriptions on certain tablets found in one of the Indian mounds in this vicinity. A Mr. Patterson of Pittsburgh undertook to publish the romance under the title The Manuscript Found, but failed to fulfill his contract. For two or three years the manuscript remained in the hands of the would-be publisher, and one of his printers, Sidney Rigdon by name, copied it. Hearing of Joseph Smith's digging operations for money through the instrumentality ofi necromancy, Rigdon resolved that he would turn this wonderful manuscript to good account and make it profitable to himself. An interview took place between Rigdon and Smith, terms were agreed upon, the whole manuscript underwent a partial revision, and in process of time, instead of finding money, they found curious plates, which, when translated, turned out to be 'The Golden Bible, or Book of Mormon' which was found under the prediction of Mormon in these words: 'Go to the land Antun, unto a hill, which shall be called Shin, and there have I deposited unto the Lord all the sacred engravings concerning this people !' After reading all the contemporary evidence given by persons who knew Spaulding and had heard him read parts of his manuscript, and who have compared it with TheBook of Mormon, one can hardly doubt that the wandering evangelist and antiquary, Solomon Spaulding, wrote the first draught of The Book of Mormon at the little village of Amity."

The College at this era was in the spot-light of fame chiefly because of the glories of the first temple, (not the first building, however,) Dartmouth Hall, a metropolitan pile in the wilderness. Its fame penetrated even to the Philadelphians to whom it seemed as far away and as in deserto as do even the Solomon Islands today. In October, 1787, Matthew Carey filled a column of the American Museum with his wonder: "In October, 1786, a new edifice was erected— said to exceed for magnitude any building in New England, being 150 feet in length and 50 in breadth, three stories high, constructed in the most elegant manner perfectly agreeable to the most refined taste of modern architecture." The conclusion of the article would seem to qualify Carey as the original charter member of the Dartmouth Outing Club: "It is worthy to remark, that the climate is so favorable, and the air so salubrious, that there has not happened an instance of mortality among the students since its first settlement. It is situated in about 43 d. 30 m. N. L." This opinion, however, was not shared by Timothy Dwight of Yale, author of the resonant ode, once supposed to be immortal, "Columbia, Columbia, to Glory arise The Queen of the world and the child of the skies."

The venerable bard, touring the White Mountain region with horse and "shay" during the autumn of 1797, ten years after Carey's clean bill of health for the College, made this observation upon the then town of Dartmouth: "The village contains, perhaps 40 houses; several of which, to our surprise, were ragged and ruinous,"—a certain condescension observable even yet, perhaps—and then he records this: "When we arrived at Dartmouth we found the inhabitants just recovered from a severe dysentery. Of 520 persons, the whole number in the village, 220 had been sick, and 22 had died." Can it be that the campus pump was even at that primitive era doing its deadly work, and is it possible that the freshman class contained at that early date as many as 220? But I speak as one who remembers the "roaring" 1880s. Prexie Dwight visited the College again in 1803 and of all he saw, and he saw it all, he commended only one thing: Dartmouth was mighty in the singing of pious hymns. "I attended divine service in the church at this place, and never, unless in a few instances at Wetherfield, many years since, heard sacred music which exhibited so much taste and skill as were displayed here."

It is the literary side, however, of this early Dartmouth that has occasioned the most of my jottings. In 1790 the students played "The French Revolution" a most ambitious piece, of native authority, perhaps. It was produced a year later at Windsor, Vermont, perhaps with Dartmouth actors and then it drops from dramatic history. The early College seems to have been rich in dramatics. In the class of 1795 was a professional dramatist, David Everett, whose first play Daransel was a popular success at the Federal Street Theatre, Boston, during the whole season of 1799-00. Other plays followed, but it is not these that have added his name to the roll of the makers of classics, it is his lines, once household words,

"You'd scarce expect one of my age, To speak in public on the stage. . . . Large streams from little fountains flow, Tall oaks from little acorns grow."

Thus early did Dartmouth begin to enrich American literature.

In the next class was Thomas Green Fessenden, "the American Butler," certainly the first real American humorist. A whole paper could be written on this delightful Yankee poet. The quality of his humor, however, I will illustrate by a single episode that came under my eyes" only a few days ago.

In the Philadelphia Port Folio, March, 1801, Joseph Dennie, the editor, a generation ahead of his time, deplored the tendency, then all but universal, of American poets to copy servilely images and expressions from the English writers "which are most ridiculous when associated with descriptions of our own homebred nature" and he exhorted American poets "to clothe their ideas in coarse homespun rather than in the frippery of foreign garniture." He would recommend "a sort of non-importation agreement," and rule out all nightingales, Philomels, skylarks, and eglantines, and the like. There is something refreshingly modern in the way the Dartmouth Yankee Fessenden came back at him. Taking the editor at his word he sent in this, which Dennie printed:

A MOST DELICATE LOVE STORY My Tabitha Towser is fair, No guinea pig ever was neater, Like a hackmatak slender and fair, And sweet as a muskrat or sweeter.

My Tabitha Towser is sleek When dressed in her pretty new tucker, Like an otter that paddles the creek In quest of a pout or a sucker.

and so on through fifteen home-spun stanzas.

Dennie, himself by the way, in many respects the most significant American literary figure before Irving, comes into the Dartmouth story. In July, 1793, was founded the Eagle: or DartmouthCentinel, edited by Josiah Dunham, class of 1789, Preceptor of Moor's Charity School. It was the Eagle that started Dennie on a literary career; to its columns he contributed some fourteen of his Farrago Essays. Certainly this Eagle should have flown down nearer to our own day, for about it gathered a remarkable school of poets and essayists,— "Florio," "Amintor," "Monitor," "Tim Pandect," "Pastorella," "Laura" and many more who came nearer to making Hanover an American literary centre than it has even been since. Its poetical department, its chief glory, was "The Aonian Rill," a stream the flow of which has been intermittent at Dartmouth even to our own day. A decade or so after the Eagle, it burst forth again in the Dartmouth Gazette. Only one sample of its waters is at my hand at present, a limpid drop, quoted in high glee by Dennie in 1804:

Vermont, less wise than sister France And more than fifty times as odd, In spite of Federalists and chance, Has voted that she'll have a God; And gravely fix'd her choice upon "The mild, the modest Jefferson"! !

Even the president of the College had literary ambitions in those early Aonian Rill days. In February, 1801, this news item appeared in a journal as far south as Pennsylvania:

"At Boston, proposals have been issued for printing in the usual Americanway, a learned and profound work from the pen of Dr. Wheelock, president of Dartmouth College, in New Hampshire, entitled 'A Philosophical History of the Advancement of Nations, with an Inquiry into their Rise and Decline.' The author of this book has the reputation of being one of the- most studious men in America. Nor has he read in vain, or filled his shelves without enlarging his mind. Endowed with a memory faithful to retain and a judgment subtle to discriminate, Dr. Wheelock certainly will supply the learned world with a volume which the historic muse will not disdain to arrange among the more valuable of her records and rolls."

The italics are in the original: "the usual American" way was by subscription. The historic muse may not have disdained the book but it is evident that the lesser gods of the subscribing world did. Certainly they did not appear in sufficient numbers to warrant its publication. I wonder if any fragment of the manuscript has been retained by the College.

What the Prex couldn't do his professors evidently could. In the Boston Monthly Anthology of March, 1806, appears the notice of a highly successful volume, "The New Hampshire Latin Grammar by John Smith, Professor of Learned Languages at Dartmouth College." Already it was in its second edition.

But if President Wheelock could not produce books that subscribers would buy he himself could buy the subscription book of another author when he found it of value. I have discovered recently that Alexander Wilson the ornithologist and poet is a more substantial literary figure than I had supposed. In 1808, on his tour through New England to solicit subscriptions for his proposed work on ornithology, he visited Hanover and sold a copy to President Wheelock, no small feat when it is remembered that the price was $120 a copy. I wonder if the volume is still in the college library. Wilson sold only seven copies in the whole state and, after three months of most diligent canvassing, he sold only forty-one in all New England. His visit to the land of the highbrows evidently did not leave with him pleasant memories: "My journey through almost the whole of New England," he writes to a friend, "has rather lowered the Yankee in my esteem." Even Harvard College he found crude and rough. "Cambridge," he wrote, "has a fine library, but the most tumultuous set of students I ever saw." But in Hanover, after once he had reached it, he found real refinement and hospitality. This is what he wrote October 26, 1808, in a letter home to Pennsylvania:

"From Portland I directed my course across the country, among dreary savage glens, and mountains covered with pines and hemlocks, amid whose black and half-burnt trunks the everlasting rocks and stones, that cover this country, 'grinned horribly.' One hundred and fifty-seven miles brought me to Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, on the Vermont line. Here I paid my addresses to the reverend fathers of literature, and met with a kind and obliging reception. Dr. Wheelock, the president, made me eat at his table, and the professors vied with each other to oblige me."

Potent, however, as was this early Aonian Rill in the northern wilds, it was not strong enough to satisfy the literary cravings of all its. students. Joel Barlow, later to be the tremendous poet of The Columbiad, that Pliosaurus of American poetry, lingered for a time and then sought the stronger poetic waters of Yale, and George Ticknor after having made a unique drawing of old Dartmouth Hall ran away to Harvard. Daniel Webster, however, to the joy of all the later sons of Eleazar, remained supporting himself by canvassing for Weems' new Life of George Wiashington, the biography it will be remembered that gave currency to the cherry tree and hatchet fable. And again, by the way, a fascinating paper might be written on the methods used by early sons of Dartmouth to remain in college despite resangusta domi. Fessenden, for instance, taught singing school, it may be in Aetna.

I cannot omit mention of Samuel Lorenzo Knapp of the class of 1804: I take huge pride in him. In 1829 he published the first regular History of American Literature; in 1886 C. F. Richardson published the second (Tyler's earlier volume was the study of a period.) And it is worthy of note that the first regular college course in American literature in New England and the second ever given in the United States was the one that "Clothespin" started in 1883. The first was given by Moses Coit Tyler in 1875 at the University of Michigan. In this field truly the history of Dartmouth has been unique.

I have often wished someone would write of the Phi Beta Kappa orators and poets who for more than a century brought grace and culture and wisdom into Hanover. And to it should be added a list of other noteworthy visitants, like Matthew Arnold. Dartmouth has often displayed fine daring in her invitations. She called that superlatively dangerous heretic Ralph Waldo Emerson to lecture six days after his devastating Divinity School Address and she was the first college to recognize even remotely the tabooed Walt Whitman. He had been judged to be too foul even for Washington politicians and had been kicked out of office by their chaste toes because he had written a naughty book, and right in the midst of the rumpus Dartmouth invited him to her sacred platform. And he read her his strongest poem: "Like a Strong Bird with Pinions Free." What a day that was for Dartmouth; how little she realized it then and how proud she is of it today! but thereby hangs a delicious tale which every man of the early seventies knows and which I would tell were not my space long ago more than filled.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhatever be the time selected

February 1924 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN THE SEVENTIES

February 1924 By Samuel L. Powers '74 -

Class Notes

Class Notes$1000 REWARD PEARL NECKLACE

February 1924 -

Article

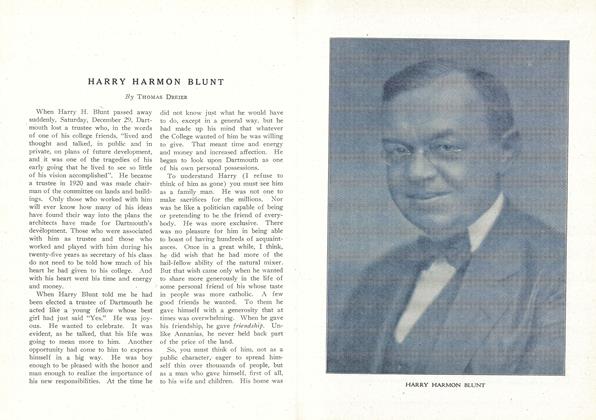

ArticleHARRY HARMON BLUNT

February 1924 By Thomas Dreier -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

February 1924 By H. Clifford Bean