That breeziness of the boreal climate which is supposed somehow—by the poetic license of our famous bards—to invade the circulatory systems of all Dartmouth men, prompts especially in the winter season a reflection on the scope and purposes of the Outing Club. This organization is now something like ten years of age and is much more than a lusty infant. It has become part and parcel of the distinctive Dartmouth life, sufficing in an unusual way to differentiate our college from others similar in size and situation. We recall no other, at all events, which has made so successful an institution out of its student organization for the enjoyment of the great out-of-doors.

Doubtless the winter carnival is the feature whereby this phase of college life is best known by the casual outer world —but it would be a serious mistake to emphasize that as if it were all. The notable work which has been done in mountaineering, in providing shelters near and far for the comfort and use of long-distance hikers, and the manifold efforts to promote healthful sport by both field and stream, mountain trail and highroad, ought certainly not to pass unnoticed. In a general way most of us have heard of the "chain" of shelter cabins; but the latest formal report of the Club mentions them by name as Tucker, Moose, Cube, Armington, Great Bear and Agassiz Basin—names usually suggestive of locality with sufficient clearness to identify them. The work of committees engaged with map-making, trail-blazing and the provision of accommodations have it in their power to do, and as a matter of fact actually do, much that is of benefit far beyond the college itself.

The functions of the Club are dual— perhaps even more, but surely dual. It is an organization which contributes directly and positively to promote a healthy undergraduate interest in out-door life and sports; and incidentally it advertises the college in the most desirable of ways. So important is the organization in the polity of the college that its president has been made an ex officio member of Palaeopitus. So popular have its activities come to be that a new ski-jump has been found necessary for the uses of winter sportsmen in order to relieve congestion at the old take-off just above the Vale of Tempe.

The latest available figures show an enrolled membership of almost half the college—45.5 per cent, to be exact. It seems not too much to say that as a real incentive to general exercise of a health-bringing sort, the Outing Club infinitely surpasses our other familiar sports, organized or unorganized.

In connection with the Outing Club it should be mentioned that to the other notable benefactions of Rev. J. E. Johnson (1866) is now added the gift of a beautiful silver cup for the especial custody of the Ledyard Canoe Club, on which will be inscribed the names of men who make the "Ledyard Journey" from Hanover to the sea by canoe, on the Connecticut river. John Ledyard, for whom the club is named and whose name also lives in the venerable bridge to Norwich, made this canoe journey in 1773 his craft being a dug-out formed from a pine which he himself had felled on the banks of the stream and which he fashioned into the rude semblance of a canoe. Its dimensions were 50. feet in length and three feet in width. This venturesome voyager floated down the entire length of the river, tying up at night, until he reached Hartford, Conn. This trip, measuring 140 miles, is certainly somewhat short of "the sea"; but it reaches at least the head of navigation and is fairly to be designated in modern speech as "some trip."

Whether or not modern contestants for the Ledyard Journey cup will emulate the originator of the jaunt in every particular may be doubted. Ledyard took with him for food some dried venison. His stateroom was a structure of willow boughs at one end of his canoe, over which was spread a bearskin. His library consisted of two books—Ovid and a Greek Testament. Presumably one who covers the distance in our day without much Latin, or with even less Greek, will qualify as a fit and proper person to have his name engraved on the trophy-

Several of the 50-odd members of the Ledyard. Club will make the journey in the spring, according to current plans. That Ledyard himself ever canoed northward toward the Canada line is not so clear—but the Club has established shelters in that direction also; and possibly some other generous alumnus will parallel Mr. Johnson's gift by providing another cup for prowess in northward venturing, allurements toward which did not exist in 1773.

Still another activity, incidental to the main purpose of the Outing organization but in its way useful and important, is ordinary walking over the common highways. In this direction there has been some little competition for distance records, and within a short time a student of the college. Warren F. Daniell, has established a new mark for distance covered in twenty-four hours by walking 85 miles, which is the distance between Hanover and the town of Winchester, N. H., near the Massachusetts line. This is two miles better than the best previous record for this period of continuous walking. Some discount possibly should be made, since the 85-mile record was made over a reasonably level route with the assistance of some very excellent roads, where the former record of 83 miles was made over very hilly country, between Littleton, N. H., and Lyme. But in such a problem it is naturally difficult to estimate what allowance, if any, ought to be made, since those who go up a hill naturally enjoy a compensating advantage in coming down again, whereas the level country walker merely averages this effect.

One hesitates to bestow too much reclame upon continuous performance like this, however interesting the records may be, because they evidently miss the real point in a walking tour and do not at all represent the usual intent and purpose of the Outing Club. In an ideal walking tour, such as the successive mountain trail trips involve, the distance covered in a day's jaunt would not be over 20 miles, and often less. One who for five or six days walks from 10 to a dozen miles along a purposeful trail, without haste and with due appreciation for what he sees, gets much more out of the exercise than one who pumps through 85 strenuous miles between midnight and midnight. Let us distinguish, then, between the general scheme of our outing events and the occasional establishment of a long-distance record- which latter is, after all, a "stunt" and is not likely to be frequently emulated by the generality of student members.

The selection some weeks ago of a new football coach to take the post vacated by Mr. Spears laid emphasis on the custom now in favor at Hanover of choosing for this difficult and responsible position a younger man, rather than an older—one more recently from the actual playing of the game with the Dartmouth team. The comparative worth of the two possible alternatives—an older or a younger player—must be judged by the results; but evidently those in authority over such things have been impressed by the showing made under the leadership of younger men. Mr. Canned, upon whom the choice fell, is a recent captain—more recent than Mr. Bankhart, who was also prominently mentioned for the position.

Naturally this course differs markedly from that of many other colleges, some of them extremely successful in the realm of football, which have arrayed numerous veteran players as the season progressed for the instruction and assistance of the undergraduate members of their teams—such veterans often going back for a decade or so to their own active participation in the sport.

On the face of the matter it would seem that the odds favored the course taken at Dartmouth in preferring as coaches those most lately engaged as players. "An older soldier—not a better," somehow- recurs to the mind. Men most lately in full career as college players ought to be in closest touch with the game and with its constantly varying requirements. But the working out of a theory may prove that it has defects discoverable only in practice—and one suspends judgment in consequence, merely remarking that abstract probabilities augur success for the Dartmouth idea. No comparison is possible between such a sport as football and such a sport as rowing—in which latter men have remained as successful coaches down to a surprisingly mature age. Rowing changes its essentials hardly at all. Football, as played today, is hardly understood by those who played it a dozen years ago; certainly not by those who have been two decades out of college.

A touch that would have delighted Mr. Chesterton was given to a remark by Dean Laycock at the recent dinner of the Boston alumni, when he said of the democracy of Dartmouth that it "insured to the rich man just as good a chance as to the poor." This was no slip of the tongue. It was a deliberate utterance—and a wise. The point it emphasized is one too little heeded in the modern day of proletariat worship—a day in which one readily conceives great possessions to be criminal and in which one half-consciously writes down the rich man as necessarily unworthy just because he is rich.

People naturally do rush to extremes. Having revolted from the absurd notion that because a man is rich he must therefore be better than any one else, we go incontinently to the opposite pole and assume that because a man is rich he must necessarily be worse than any one else. The fact that, independently of his pocketbook, a man may be either good or bad is commonly overlooked; and it is the righteous wish of the Dean that in Dartmouth men be given the chance to show what is in them, unembarrassed by extraneous facts as to poverty or riches.

For the poor man the road is usually made plain. The sentiment of our day endues a poor man plenteously with heavenly gifts. They are gratuitously ascribed to him as compensation for the fact that he has no plethora of worldly goods. Conversely, it is fashionable to assume that if a man is wealthy he must be spoiled. Right there comes the Dean's salutary principle, enunciated above, with its demand that no man be approved or condemned on the immaterial ground of his estate, but that a free channel be afforded for the demonstration of what each man is. Not what he has, but what he does, is undoubtedly the safe guide.

No one who has rubbed much against the world can have overlooked the fact that there is a snobbery of the poor quite as surely as there is a snobbery of wealth and fashion. It is equally unjust with the latter. It is harder to rebuke. It is actually no easy matter to "give the rich man as good a chance as the poor." It may be, of course, that the rich student is a degenerate fool—but it won't do to assume that off-hand, as the snobbery of poverty generally insists upon doing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCHARLES DOE, 1849

March 1921 By JUDGE JOHN ELIOT ALLEN '94 -

Article

ArticleA REPORT TO THE ALUMNI

March 1921 By JAMES P. RICHARDSON -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

March 1921 -

Article

ArticleWEBSTER LETTER PROPHESIED TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH

March 1921 -

Books

BooksPUBLICATIONS

March 1921 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH LIFE IN 1820

March 1921 By JOHN GROSVENOR DANA '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleOBSERVANCE OF DARTMOUTH NIGHT CANCELLED

November 1918 -

Article

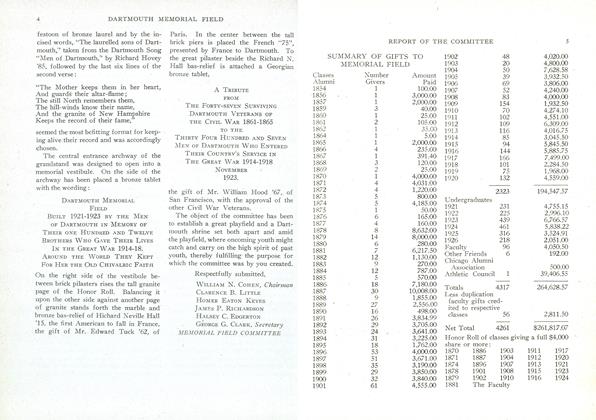

ArticleSUMMARY OF GIFTS TO MEMORIAL FIELD

August, 1926 -

Article

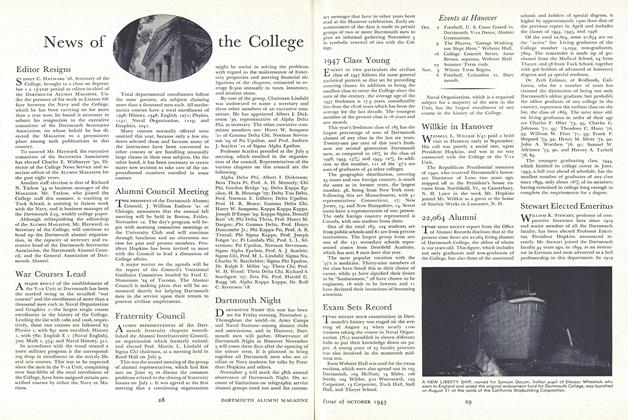

ArticleWillkie in Hanover

October 1943 -

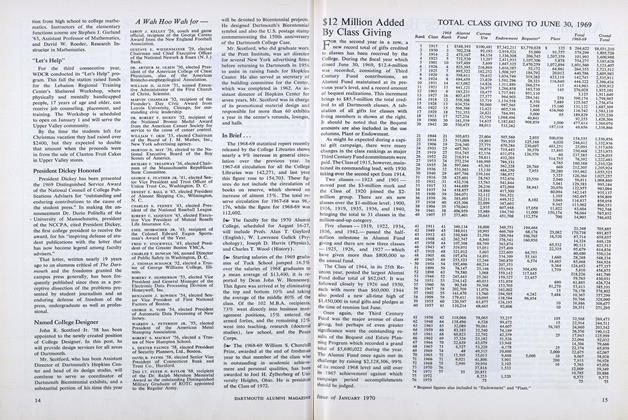

Article

ArticleNamed College Designer

JANUARY 1970 -

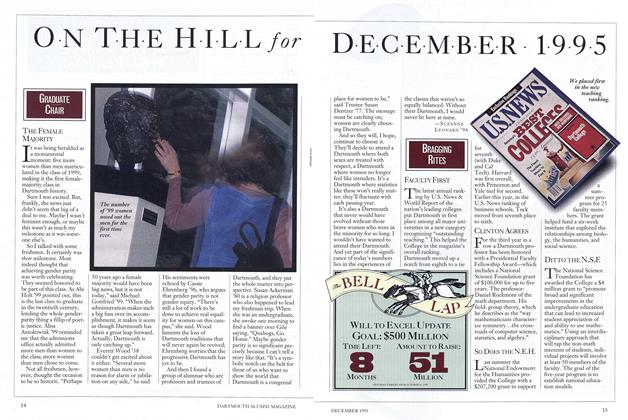

Article

ArticleSo Does the N.E.H.

December 1995 -

Article

ArticleHanover's Most Illustrious Woman

November 1937 By GABRIEL FARRELL '11