the interest of older students and alumni is likely to center—once the question of the number of new students is settled—in the changes in the physical plant. These are usually indicative of material progress and also awaken the interest of such as relish changes in a familiar scene.

It may be stated that the summer has worked considerable alterations at Hanover, most notably in College Hall. That useful building has undergone some radical improvements inwardly, including a complete renovation of the kitchens, the construction of a serving room, the provision of a new refrigerating plant and the installation of an up-to-date cafeteria in the former billiard room. It is possibly too much to expect the student body to vary the American custom of mispronouncing that blessed word "cafeteria"— which an untravelled populace persists in accenting on the "te"—but beyond doubt the institution by any other name will smell as sweet and will eke out the college facilities for catering to its steadily increasing student population. The cafeteria is planned to accommodate a hundred persons and will be operated in connection with the grill.

Changes calculated to improve the ventilating system of the building and augment the manifold uses of the large assembly room have likewise been made.

Culver Hall, that mansarded relic of the piping mid-Victorian epoch, which in an elder day was sacred to the reek of chemical experimentation and to the fervent pursuit of geology under the genial Hitchcock, is also announced to have undergone at least a minor operation whereby its first floor has been made to give shelter to the department of fine arts. There is a certain grim humor in this allocation of quarters, because there is small probability that an artistic sense would ever acclaim Culver as an architectural ideal. Social science, which is also to be housed there on the second floor, might be conceived to quarrel less vigorously with its environment; It may be ungracious to criticise this grim old building, which has borne no mean part in Dartmouth history—but there is little prospect that Culver Hall will ever achieve a prize for possessing the fatal gift of beauty. It might be altered; but the fine old substantial flavor of the Rutherford B. Hayes period in American architecture would hang round it still.

The useful science of chemistry, so long associated with Culver, now moves to its new temple named in honor of the late Judge Steele—finishing touches having been put to this important building in the closing clays of the vacation so that it might be ready for use when the term began. This marks a substantial advance in the equipment of the college in what our British cousins usually call the "'modern side," and it brings the department well to the fore among American colleges of our class.

It remains the crying need of Dartmouth to provide similarly well in the matter of its library. Wilson hall, the pride of a generation ago, is absurdly inadequate for its purposes now; and the provision of a library building properly supplied with books may without risk be nominated as the next outstanding task. Wealthy alumni and intending benefactors not actually of our fellowship may well ponder this potential avenue of selfexpression. For the care of the body, Dartmouth has done more than admirably in the provision of her huge gymnasium, the swimming hath, and the newly remodelled Memorial Athletic Field. For the shrine of books she has thus far made no adequate provision. It cannot be much longer delayed. When all is said and done it is books that we come to college to find—books to read, as well as books to study for improvement.

Since we wait long for this, let the thing he done worthily when it is done—something built not for an age but for all time, if possible. Indeed it is well that we have not rushed upon this problem precipitately. Library architecture has not yet struck its unquestioned twelve. Admirable within, the Widener Library at Cambridge is uninspiring without. Possibly it is not amiss that we bide a wee.

Another novelty not of an architectural nature will be found in the creation of the office of Dean of Freshmen—a task of peculiar responsibilities—which is to be filled by Mr. E. Gordon Bill, lately professor of mathematics. Quarters for this official have been planned in the basement of the administration building and may well become historic with the coming years.

Minor changes affecting more familiar structures include the provision of a new and adequate organ in the college church and certain alterations in the gallery of Rollins chapel to improve the conditions there with reference to the splendid Streeter organ and (he choir.

Hallgarten, better known to an elder generation as Conant and by such associated with the time when agriculture flourished as a neighboring adjunct of the academic college, has been sufficiently renovated to make it habitable by students. In point of outward show it seems to. fall into the general class with Culver—a survival of the dark hour which traditionally ,comes just before dawn. Hallgarten may not 'be with us many years more. Wherefore let us cherish it tenderly! It isn't pretty despite its idyllic name, and to make it so would over-tax the fallible human hand; but it has been long with us and has sheltered many a worthy soul.

In the same general district one may mention the new fraternity house of the Alpha Delta Phi, now ready for occupancy, on the site occupied by the severely plain, but by no means undignified, brick structure so long sacred to the mysteries of that Greek letter society.

Mention having been made of the new organ in the college church—which is being installed to take the place of the one given so many years ago by the late Hiram Hitchcock,—it is interesting to recall that the present donor is Mr. Walter Clark Runyon, a lineal descendant of Eleazar Wheelock, and now a resident of Scarsdale, N. Y. In view of the great value of music in religious services it is welcome to find that in this respect the venerable church at Hanover is to be provided with so adequate an instrument. It is odd that this, the noblest of musical contrivances applied to the praise of God, should have had to make its way to popular favor against what was originally an adamantine prejudice in the minds of such as derided pipe-or-gans as "kists o' whustles." There was a day, however, which readers of professor Bartlett's delightful reminiscences will recall, when some of the older musical instruments of this nature at Hanover merited the description, owing to the irreverent manipulations of mischievous sophomores.

Renovation in respect to the church is not confined to the provision of the new organ. The building has undergone a general overhauling within and without to fit it worthily for the observance of its 150 years of life. As the old building emerged from its previous renovation at the hands of McKim, Mead & White, it was a noble example of New England ecclesiastical architecture—but it is destined to be even more so henceforth. In age almost coeval with the college, it deserves and will receive full measure of Dartmouth's love and veneration.

One is tempted to incidental discussion of the proper relation between religion and the college as an institution. It must be admitted that original ideas have greatly changed from the days when most colleges were denominational affairs, founded with the principal aim of recruiting the ministry. The number of men now passing from the colleges to the church is deplorably small by contrast with the numbers graduated; and the reasons for this have furnished the material for interminable debate. Religion might seem to have modified itself greatly since the first College church was built and dedicated on this site—unless we are very careful to distinguish between religion and theology. It is safer to say that though much is taken, much abides —and that the things which abide are real religion.

The task of any church, especially a college church, in squaring itself and its functions to the needs of its day is no easy one. It often seems to involve surrenders which ought not to be made and yet what alternative is there, save destruction, to a cheerful acceptance of revealed truth as it appears under the growing illuminations of time? To deplore the decay of ecclesiastical authority is possible only where that which is lost finds no adequate replacement. Meantime what of the relation between religion and scholarship, in a time when scholarship tends toward the secular ?

There is much to be said both for and against compulsory worship in the colleges, whether represented by church or chapel services. Increasing numbers much more than decreasing faith have operated to destroy the requirement (which Dartmouth thus far retains) of attendance upon religious exercises. Yet the MAGAZINE feels, in spite of all contrary argument, that retention is desirable, as long as it be physically possible, in some part because even indifferent young men are subconsciously bettered by the regular contact with spiritual things.

It would be rash to say that in the study of God's handiwork implied by the pursuance of scientific lore there was no spiritual content. "The undevout astronomer is mad"—and an undevout chemist may well be in the same category. Nevertheless one thinks of the "modern side" as less obviously spiritual than the "classical" was; and if the college churches can manage to link up the advances of science to the undying, unchanging realities of actual religion, they will perhaps be doing their most useful work.

A word, then, for the college church and its vital relationship to the modern scheme of things. One concludes that it is rather more necessary now than ever before—more so, surely, than when most students were embryo clergymen with well formed beliefs operating as a levamen probationis for the cause which the church represents. To a materialistic age the church must interpret God in the light of what men know of his universe ; and it must do this in terms which the modern intellect does not reject.

No doubt every day should in its proper sense, be Dartmouth day with alumni of the college—but in practice it is well to continue and intensify the custom which has grown up in the observance each autumn of a single date as "Dartmouth Night." To gather the sons of the college from afar on this occasion so close to the opening of the college year and to hear afresh from eloquent lips the message of the Dartmouth spirit is not amiss. It is not an occasion for the inculcation of old lessons to veterans of the fellowship, but rather a time when veterans of the fellowship should vie in making real to those newest come to our circle the reality and meaning of the impalpable, but potent, thing which we regard as our moral trademark. "The Dartmouth spirit" might so easily become a cant phrase—sound and fury, signifying nothing. It is important that hopeful neophytes at the shrine become early imbued with the wholesome notion of what our spirit is—hear it described first by authoritative lips and then observe its manifestation in deeds.

That the Dartmouth spirit is no mere formula, but is a living, vitalizing thing, needs to be learned at the threshold of the freshman year. It is well to guard against undue formula-worship, especially in an era much given thereto. 'Dartmouth Night stands for very much more than the reiteration of a phrase. It is a sort of birthday, commemorating not an event but a principle. To be given an idea of that principle (which those of us who best know it can least clearly define) is the need of every entering class; and Dartmouth Night stands as the symbol thereof. It is only the symbol, however. The task of discovering for oneself the very essence of that spirit is not greatly different from what our forefathers called "conversion." One works it out in fear and trembling for oneself, in the light of what one sees in others. Two important publications will soon be available for distribution—one the Register of Living Alumni, more commonly known as the Quinquennial Catalogue, and the other the Sesqui-Centennial book. The former requires no comment. It is the roster of our fellowship and any alumnus may procure it on application by paying one dollar.

The Sesqui-Centennial book, which is handsomely printed and illustrated, may be had for the price of $5 a copy; and it is quite safe to say that no alumnus can afford to be without one. In addition to a full report of the ceremonies which marked the observance of the 150th anniversary of the college, there will be found a succinct summary of the college history by Professor John King Lord and a detailed description of the college plant, its trustees and officers, with abundant photographic detail to make real to every reader the Dartmouth of the present day.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE'S RELATIONSHIP TO THE COLLEGE

November 1921 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Sports

SportsFOOTBALL

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleTWO DISTINGUISHED VERMONT ALUMNI

November 1921 By JAMES FAIRBANKS COLBY '72 -

Article

ArticleMEMORIAL FIELD FAST BECOMING A REALITY

November 1921 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

November 1921 By Fletcher Hale -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1921 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh

Article

-

Article

ArticleNew Hockey Rink

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleCivilian Positions

February 1943 -

Article

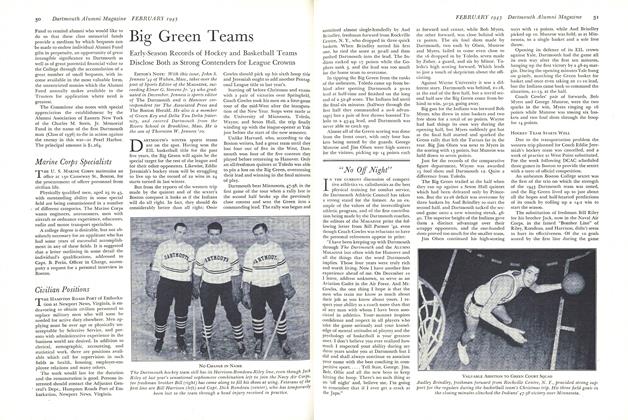

ArticleFunds Given for Medical School Dormitory

October 1961 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

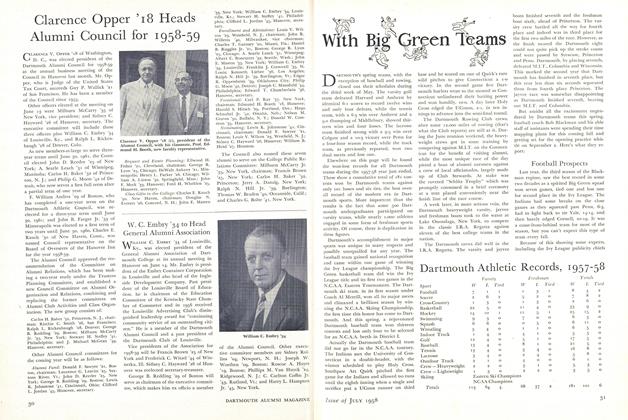

ArticleFootball Prospects

July 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Stephanie Edwards '00