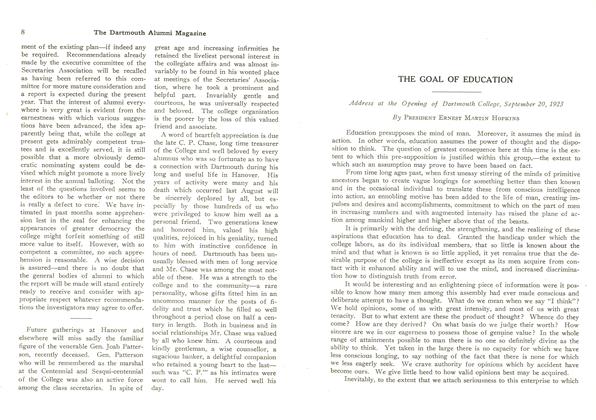

It is the office of the President of the College, from time to time, to act as spokesman of the Faculty and of the Trustees, to whom the direction of the College is entrusted, and to formulate and to enunciate those principles which govern its conduct.

Common understanding is the first requisite for that common loyalty, possession of which gives effectiveness to the efforts of any group working together. It does not do for those of us who remain associated with the life of the College to disregard the fact that the undergraduate life is constantly changing and that iteration and re-iteration must be made periodically of those vital axioms of college life which are accepted as fundamental to college policy and college procedure.

I am taking the occasion this morning, therefore, at the beginning of our work together to speak briefly, and only in the way of suggestion, concerning some points of view which at other times and in various places we will discuss more in detail.

Each year brings some measure of sorrow in its chorus of disappointment and hurt protest from men who have not chosen to show the individual promise which would justify the College in continuing its mutual relationship with them, to the exclusion of other men, and the plea is made,—"We did not understand".

Each year, too, the expressed regret is frequent by out-going senior or young alumnus that earlier knowledge was not had of the relative values of the college opportunity and that more discriminating distinction was not made between essentials and non-essentials of college life or in regard to the use of time.

In regard to such matters the College can do little more than to offer the opportunity. The individual student makes the decision and upon him rests the responsibility, of which none can relieve him, of determining the real advantage which he shall claim from membership in the College. To those men, meanwhile, to whom an altruistic motive is more appealing than one of even intelligent self-interest, it is to be said that in the last analysis the worth of the College to society at large is dependent largely upon the spirit of receptivity among the undergraduates to those purposes and ideals of the College which throughout its history have chiefly made its work vital.

Long years ago Jonathan Edwards, at about the average age of the mass of men here gathered, recorded in his diary these words: "I frequently hear persons in old age say how they would live if they were to live their lives over again: Resolved that I will live just so as I can think I shall wish I had done, supposing I live to old age".

If the years spent here are to be of major advantage, it would be a not unprofitable bit of speculation now for each man beginning the new year in Dartmouth to-day to query what are the satisfactions in life of which he will later wish to have made himself the possessor and what are the conditions in life of which he will subsequently wish to be the understanding master rather than the bewildered subject.

That method of more quickly and easily securing a higher education than otherwise would be possible, which we designate as "college", is not the inherent right of every man. It is a privilege which has been made available in our colleges by persevering effort and continuing self-sacrifice and generous benefactions, sometimes to the point of self-impoverishment, on the part of numberless men, through long periods, as at Dartmouth for more than a century and a half. It is an invaluable privilege, rightfully to be claimed only by men who will cherish it and who have or will cultivate the ambition to realize the ideal for which it stands, namely that they may know the truth and do it.

If it seems a harsh saying or even inappropriate at this time to emphasize the point that not all men are entitled to the advantages of the higher education, still the importance of the fact requires the statement of it; and if any man here claims the privilege without intention of utilizing its benefits for his own intellectual advancement and for the benefit of society at large, he not only sells the patrimony, which might be his, for a mess of pottage, but he as truly denies to Dartmouth the opportunity of rendering to society the full service the college desires to render to it.

It is to be assumed, of course, and is assumed today that all gathered here are deserving of the opportunity extended, but experience denies to our reason the confidence our hopes would crave. Unless Dartmouth's selective processes, which have granted access to its benefits to a small minority of those who have sought admission, have worked with unwonted accuracy, there will fall by the way-side from the freshman class alone within the next four years three hundred men because of untoward circumstances, among which lack of mental and moral stamina will not be half infrequent enough.

It is, as I have said before, rarely the case, however, that a man of this group, separated from the College, does not look back in tragic disappointment and regret and say how he would do were the privilege his again which he has failed to claim. It is, therefore, alike out of great concern for the individual man and out of deep solicitude for the College that we would ask each man this morning to think as seriously as he. will what it is that he will wish at some future time that he had got from this college.

The beginning of the year is a desirable time, likewise, to emphasize anew the fact that the goal of the College must be something else than mediocrity, and that in some respects the man who simply strives "to get by" instead of to realize his best possibilities harms himself and handicaps the College more, perhaps, than the man who eliminates himself from the necessity of further consideration.' The college opportunity is one that ought to be extended to the widest extent practicable to men of possible attainment who will strive, for out of a common spirit of striving will most naturally develop those qualities of sturdy and virile superexcellence in the exceptional man which cofttributes to the world's leadership or adds to civilization's store of knowledge. In a united effort to achieve the end of supreme excellence we will still have 'much that can not be classified as above the mediocre. But, if it were conceivable that we should accept mediocrity as a goal, we would have futility to a degree that would render profitless all else that we did. Let us, then, at least aspire to the heights and let us climb as high as in us lies!

In this connection, I might add in answer to those who have questioned the avowed desire of the College to raise the intellectual level of the mass rather than to confine itself exclusively to effort to develop men of the quintessence of intellectual capacity, that were the latter the method by which to secure the result, still it is not unessential to have many men intellectually qualified to recognize and to accept wise leadership as well as to produce the few men highly qualified for leadership.

In regard to the relationship of the official college with the individual student I am not entirely clear whether those responsible for the direction of the College ought to pay far more attention to the wishes of the individual man among the undergraduates or whether they ought to pay far less than they do. It is true to some extent that the College has an obligation to meet the thoughtful desires of the individual student, but on the whole I believe this obligation to be more to the desires which will be those of the graduates of two or three decades hence than it is to ephemeral wishes of the undergraduate of the specific time.

The age is one in which outstanding accomplishment is needed and demanded. Our colleges can be no more quickly nor disastrously damned than by simply meriting a faint praise. They must be positive in their influence and not negative. They must teach and reiterate the allegory of the garden of Eden, that man degenerates when relieved of all necessity for toil and struggle, and that this principle has (through the ages been proved as true of individuals as of nations. They must teach the respect due authority rightly held, for only by the recognition and by the exercise of authority can chaos be avoided and the orderly progress of mankind be insured. And at the same time they must teach that no authority is all-admirable nor allpowerful nor unchangeable that does not spring from the essential principles of goodness and of truth.

Looking ahead to the problems of the life of changed conditions, for the meeting of which we must seek preparation in our years here together, the outstanding fact is that the future is to be a period in which human relations of men. one with another, are to he of supreme importance. It requires no involved argument nor lengthy exposition to prove that distance as a prohibitive factor in life has been largely eliminated. This is as adequately demonstrated by the motor cars parked at the beginning of the trail to the fishing hole in the north country which was formerly all but inaccessible, or by the manufacturing statistics of the Ford Manufacturing Company, as by volumes of descriptive writing. This all means closer living together and that our everyday thinking and our everyday conclusions must be in terms of the group rather than in terms of the individual, and it all implies likewise modifications in the conceptions of individual freedom and liberty, markedly limiting the individual's, right to independent action as compared with times past.

The peculiarity of civilization is worthy of note that the mass of individual characters does not necessarily define group character nor signify national character. The American stock, for instance, has individually been kind and sympathetic, probably beyond compare. "But collectively it has been too oftenself-absorbed and potentially cruel. It is the responsibility of the College and of college men to work toward a correction of this condition for the new era so that while the incentives for individual selfdevelopment are preserved, solicitude for the welfare of the group shall replace a solicitude which has been too largely for self and self's possessions.

In this transfer of emphasis at will require maximum intelligence and constructive ability to think straight and courageously if we are to avoid creating new evils that will largely neutralize the benefits of ridding ourselves of the old ones. The tendency is evident all too frequently, among men who are giving anxious thought and interest to the affairs of those to whom social justice has been long delayed, to condone abuses and the results of new bigotries among those for whom this new concern is felt which will be as detrimental to society in the long run as are those faults which are being corrected. The educated man cannot legitimately allow himself thus to be emotionally influenced in as delicate an assignment to the realm of the intellect as the defining of a new social formula for the enrichment of the advancing civilization of the new era.

Particularly, in the transfer of solicitude from Personal interest to group interest we should avoid the evils of standardization, for social standardization necessarily is the enshrinement of mediocrity, and precludes those outposts and salients of ability established by individual effort and individual achievement by which leadership is exercised and the possibilities of advance for the group are designated. In the process of supplanting the objectionable phases of individualism, we must carefully safeguard the respect due personalism. The old proverb that "It takes all kinds to make a world" has the element of truth that, without variations of type among human beings, progress would never have been possible.

As an aside, I would revert again to the undergraduate life of the College and present for the consideration of men of the student body the conviction that here among us the influences are too much towards hammering out on the anvil of conventional sentiment a standardized type. Not that this tendency may not be too much present in American colleges in general, but our present concern is with Dartmouth life! Given common convictions against the cheap, the low, the unintelligent and the evil, the greater the variety of types and of attributes among Dartmouth men, the stronger the College will be. The evidence of the fault may be taken from less consequential things as well as from more. The presence of an additional button on the coat beyond that pictured in current tailors' advertisements, a variation in the height of the belted waist-line, a slight inaccuracy in sighting the line of the part of the hair,—any of these may as possibly be a mark of independent thinking and presumable distinction as they may be an indication of moral turpitude or social outlawry. I submit this argument for the consideration of those undergraduate individuals and groups who for one reason or another are called upon to appraise their fellows.

Finally, among these scattered points upon which I have been touching, I would name one other, that it is worthy of note that the possibility of individual satisfactions in life for the college student may be more largely affected by the way in which the undergraduate utilizes his time and chooses his courses than can be affected perhaps in the rest of his natural life. There is no more pathetic figure in the world than the man without capacity for pleasure outside the narrow range of the details of his professional or business life, and this becomes tragedy when for one reason or another this man becomes detached from intimate contact with what has been his whole life and is left without background or acquaintanceship with the enrichments of life from which enjoyment and. happiness might be derived, were he qualified to know and to utilize these.

I would not underestimate the value of, nor willingly be without, the so-called practical courses. They have their vital place in the college curriculum in association with the other courses. But grave mistake is made by him who foregoes, in these years of easy access to them, the resources for life-long enjoyment made available through the influences of the cultural courses. In our preparation for life's work it is proper and even indispensable that we bend our thoughts and direct our study to some extent to mastery of some of the material of practical affairs. In conjunction with this, however, no opportunity should be lost for securing those contacts that, come what may, give access to the great and eternal values of life.

Perhaps this point can best be made by illustration. Lord Dunsany in his mythical story of "The Wonderful Window" describes the longing of a young London tradesman for the spirit of romance by which he could relieve and supplement the tedium of the day's work, and. how, at the cost of all he had, this man bought the magical window from the itinerant Oriental pedlar who had brought the treasure from Baghdad. The window, fastened to the wall of a dingy, poorly furnished bedroom, showed its owner, when he looked through its panes, a sky of blazing blue, and far down beneath him, so that no sound came up from it or smoke of chimneys, a mediaeval city set with towers. Brown roofs and cobbled streets, and white walls and buttresses, and then beyond them bright green fields and tiny streams, while on the towers, archers lolled and beneath troubadours seemed to sing. In short, all that the routines of his daily life and all the dreary hurrying life of the city denied him, here were found, and here he sat, in early morning and late at night, and dreamed with new richness and new color in his drab life, while under his other window the motorbusses roared and newsboys screamed.

In some such way each man among us needs in his daily life knowledge of thai which has been in the world and acquaintanceship with the colorful realms outside these which are the environs of his so-called practical life, if he is to realize within himself the possibilities of fulness of life. All men need their wonderful windows! and civilization needs populations in which such men are far more frequently found!

By all means let us be practical and prepare for the responsibilities of practical life, but let us not deliberately prepare to live incomplete lives in which dreams and inspired fancies and blue skies and cobbled streets, and ancient cities, and the songs of troubadours, and green fields and rippling streams have no part.

Let us rather be so exactingly practical as to insist upon securing from life the great richness which it offers to him who seeks it.

President Hopkins is always one of the most interested spectators at Memorial Field contests

Address of President ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS at the Opening ofDartmouth College, September 22, 1921.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAt the opening of a college year the

November 1921 -

Sports

SportsFOOTBALL

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleTWO DISTINGUISHED VERMONT ALUMNI

November 1921 By JAMES FAIRBANKS COLBY '72 -

Article

ArticleMEMORIAL FIELD FAST BECOMING A REALITY

November 1921 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

November 1921 By Fletcher Hale -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1921 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh

ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE IN KHAKI—WHAT THE S. A. T. C. IS AND HOW IT WORKS

November 1918 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE: RETROSPECT AND OUTLOOK

July 1919 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE UNPROVABILITY OF MAN

August 1921 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleAN ARISTOCRACY OF BRAINS

November, 1922 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

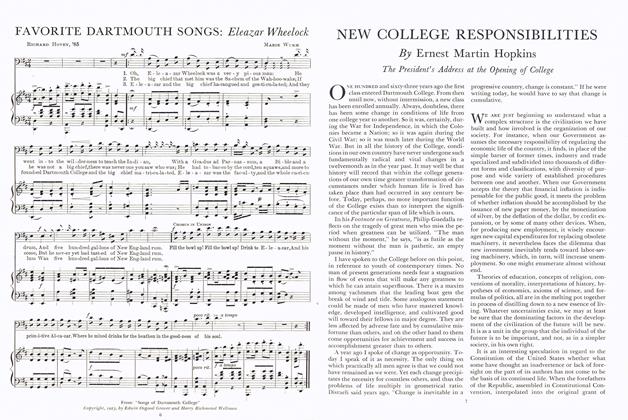

ArticleTHE GOAL OF EDUCATION

November 1923 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleNEW COLLEGE RESPONSIBILITIES

October 1933 By Ernest Martin Hopkins