PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

February 1921 EDWIN J. BARTLETT, '72PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL EDWIN J. BARTLETT, '72 February 1921

II

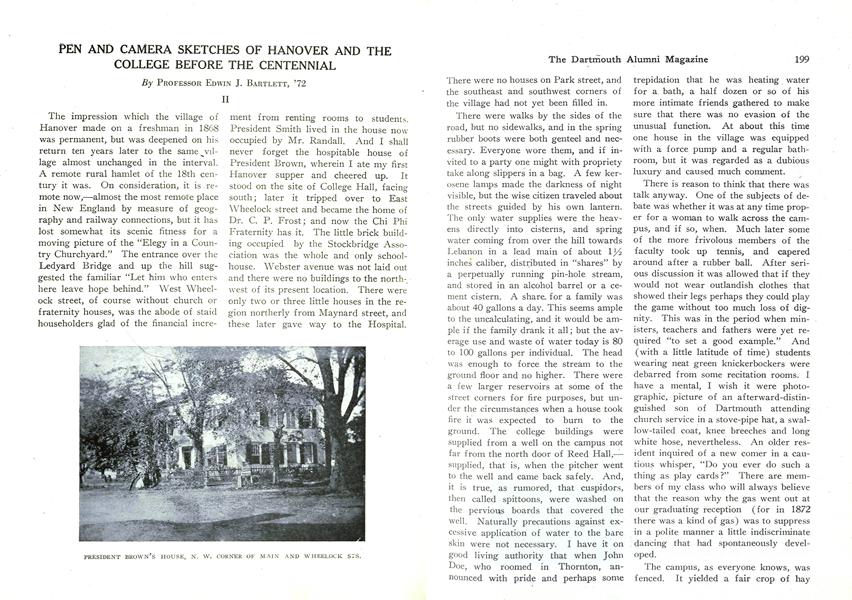

The impression which the village of Hanover made on a freshman in 1868 was permanent, but was deepened on his return ten years later to the same lage almost unchanged in the interval. A remote rural hamlet of the 18th century it was. On consideration, it is. remote now, — almost the most remote place in New England by measure of geography and railway connections, but it has lost somewhat its scenic fitness for a moving picture of the "Elegy in a Country Churchyard." The entrance over the Ledyard Bridge and up the hill suggested the familiar "Let him who enters here leave hope behind." West Wheelock street, of course without church or fraternity houses, was the abode of staid householders glad of the financial increase ment from renting rooms to students. President Smith lived in the house now occupied by Mr. Randall. And I shall never forget the hospitable house of President Brown, wherein I ate my first Hanover supper and cheered up. It stood on the site of College Hall, facing south; later it tripped over to East Wheelock street and became the home of Dr. C. P. Frost; and now the Chi Phi Fraternity has it. The little brick building occupied by the Stockbridge Association was the whole and only schoolhouse. Webster avenue was not laid out and there were no buildings to the northwest of its present location. There were only two or three little houses in the region northerly from Maynard street, and these later gave way to the Hospital. There were no houses on Park street, and the southeast and southwest corners of the village had not yet been filled in.

There were walks by the sides of the road, but no sidewalks, and in the spring rubber boots were both genteel and necessary. Everyone wore them, and if invited to a party one might with propriety take along slippers in a bag. A few kerosene lamps made the darkness of night visible, but the wise citizen traveled about the streets guided by his own lantern. The only water supplies were the heavens directly into cisterns, and spring water coming from over the hill towards Lebanon in a lead main of about 1½ inches caliber, distributed in "shares" by a perpetually running pin-hole stream, and stored in an alcohol barrel or a cement cistern. A share, for a family was about 40 gallons a day. This seems ample to the uncalculating, and it would be ample if the family drank it all; but the average use and waste of water today is 80 to 100 gallons per individual. The head was enough to force the stream to the ground floor and no higher. There were a few larger reservoirs at some of the street corners for fire purposes, but under the circumstances when a house took fire it was expected to burn to the ground. The college buildings were supplied from a well on the campus not far from the north door of Reed Hall, — supplied, that is, when the pitcher went to the well and came back safely. And, it is true, as rumored, that cuspidors, then called spittoons, were washed on the pervious boards that covered the well. Naturally precautions against excessive application of water to the bare skin were not necessary. I have it on good living authority that when John Doe, who roomed in Thornton, announced with pride and perhaps some trepidation that he was heating water for a bath, a half dozen or so of his more intimate friends gathered to make sure that there was no evasion of the unusual function. At about this time one house in the village was equipped with a force pump and a regular bathroom, but it was regarded as a dubious luxury and caused much comment.

There is reason to think that there was talk anyway. One of the subjects of debate was whether it was at any time proper for a woman to walk across the campus, and if so, when. Much later some of the more frivolous members of the faculty took up tennis, and capered around after a rubber ball. After serious discussion it was allowed that if they would not wear outlandish clothes that showed their legs perhaps they could play the game without too much loss of dignity. This was in the period when ministers, teachers and fathers were yet required "to set a good example." And (with a little latitude of time) students wearing neat green knickerbockers were debarred from some recitation rooms. I have a mental, I wish it were photographic, picture of an afterward-distinguished son of Dartmouth attending church service in a stove-pipe hat, a swallow-tailed coat, knee breeches and long white hose, nevertheless. An older resident inquired of a new comer in a cautious whisper, "Do you ever do such a thing as play cards?" There are members of my class who will always believe that the reason why the gas went out at our graduating reception (for in 1872 there was a kind of gas) was to suppress in a polite manner a little indiscriminate dancing that had spontaneously developed.

The campus, as everyone knows, was fenced. It yielded a fair crop of hay just before Commencement and a scant rowan before the opening of the fall term. This was a period, too, when the surrounding rural population as well as peripatetic fakers, mountebanks and hucksters continued to take great interest in Commencement, maintaining a lusty midway plaisance, on a small scale, at the south end of the campus, outside the fence. And the custom early noted here of the lads and lasses wandering about hand-in-hand was not yet obsolete.

There were no sewers in the place, and drainage was into cesspools or upon the surface of the ground. Why mention a gruesome matter so remote from culture? But culture cannot be separated from material conditions. The drainage and the drinking water and the culture were continually getting mixed, especially in the fall of the year; and the Bacillus Typhosis flourished like the green bay tree. One hundred cases of typhoid was, I believe, the record in one season.

Fever suggests doctors. The medical lectures began early in August and continued till about the first of November bringing a number of distinguished specialists to the village for the period of their lectures; but resident physicians were few. Before we had finished our course Dr. Carlton P. Frost had come here to live; but from the beginning I can only remember Dr. "Ben" Crosby, who, I think, did not spend all his time here, and Dr. Dixi Crosby, an old man then, who lived in the Crosby House. I had occasion to consult him twice, — once for an obstinate case of ivy poisoning, for which I remember he prescribed "Goulard's extract," purchasable at Deacon Downing's pharmacy, and once for a very painful felon in the palm of the hand, starting from a baseball bruise. After exhausting the "soft answer," that is "mush" (poultices), he resorted to the steel; upon which silence, for rhetorical effect.

Eating clubs had much more of the club-like nature than at present. A "commissary" secured members and supervised accounts; a working housekeeper, for a fixed sum per mouth filled — about 50c a week—provided room, furnishings, and cooking; waiters served for their board; and the cost of the food was assessed. It was possible to eat with a fair chance of sustaining life for $2.50 a week without tea or coffee; and the maximum of nutritive and gustatory luxury could be enjoyed for $4.25 to $4.50. It was, however, as it is now, largely a matter of hasty stoking-up regardless of the refining and esthetic influence of feeding under gentle and social conditions; and it produced a class of hasty gobblers with whom it is impossible for civilized eaters to keep pace. The breakfast menu, to conquer which has always been a race against time, was, to the best of my memory, one slab of alleged beefsteak, one piping hot baked potato, as many hot rolls as time permitted, and as a staple the pale anemic raised doughnut shrewdly constructed without the sugar which in the hot fat develops the rich caramel color of the true or mother's variety, but which was soaked in or washed down by huge draughts of sugar-saturated coffee. The bills of fare for the rest of the day are less vivid now, a little more varied it is true, but based on the theory of substance before art, and' favoring the adolescent hankering for milk and then some more milk, and pie.

My memory about ardent spirits, — the demon rum, or good red liquor, as you prefer — is vague. I know a decent-appearing, white-haired grandpa, rightly called "Judge" by many, who tells how, when a thirsty soul from the suburbs came inquiring around where he could get it, they directed him with care and secrecy to the house of Dr. Leeds; and he, the teller, chuckles over it yet.

I suppose that at the glacial period under consideration some coal came into Hanover, but if that was the case I never knew it. All the furnaces I knew burned wood and were bad actors. They smoked, as did none of the faculty. The stove was the fire king. And there were two kinds of stoves, — the "airtight," with side entrance, used in homes, one in each inhabited room, and the box or rectangular stove appropriate to recitation rooms and railway stations, stoked by lifting a hinged top that often slipped with great clatter, especially during recitations. The good old air-tight delivered the goods. It was adapted to slow over-night carbonization or to immediate incandescence which would raise the temperature of an ordinary room to 90° while you were breaking the ice in the water pitcher. And the anti-tuberculous distillate of creosote, far more wholesome than the sulfur-bearing coal gas, is reminiscent in many Hanover houses to the present day. Good rock maple wood was abundant, and after sawing and splitting was carefully stored away before nightfall; for it was one of those commodities which from time to time inherit a fashion of vanishing away, like umbrellas, house numbers, garments from the clothes-line, turkeys, text-books, and so forth, each in turn. Often on the winter afternoons four or five ox teams, the sleds loaded with "four-foot" wood, stood in the street near the hotel, and as darkness approached and sales were slow, the price for a cord came down to $3.75 or even $3.50 so that the driver might get home in time to do the chores.

The houses were migratory as has been told; and in further illustration of the slight union of buildings and their sites, — from the Inn to the Bank only two lots are occupied by the buildings of 1868, that of the express office, &c., and of the dwelling beyond; while on the other side of the street, from and including the Administration building to the little chapel of St. Thomas' Church, only two others, "uncle Jo" Emerson's occupied by the Casque and Gauntlet and the Walker house across the lane from the post office now remain. And every where the material progress of the College has been attended by houses on wheels playing "Puss-in-the-Corner", or houses in wagons traveling to the salvage heap.

The "Tontine", besides serving as a business center, was the home of several fraternities,— six at the time of its destruction by fire in 1887. I can speak only for my own, quartered in a high and dignified room extending from front to rear of the building and provided with ante-room and "guard-room". Here we gathered to supplement the meager curriculum with debates, "conversations", book reviews, essays and the reading of plays. The old ways are neither possible nor necessary now. Fellowship and hospitality have taken the place of earnestness in self-improvement; but no alumni can look back on their fraternity life with warmer affection than those of that period. How we fed on the wisdom of the great minds a year or so ahead of us ! And how we sung,—with devilish glee even so wanton a song as "Then when our little ones come on, We'll brand them all Psi Upsilon", evidently to the encouragement of legacies. And once a year, at the initiation feast, came forth the unwonted cigar to be cautiously burned perhaps near an open window. And those enjoying the usufruct of scholarship funds at the expense of the "iron clad" pledge agreed with Rip Van Winkle that "this time does not count."

No one can' speak with accuracy of Hanover's business men from the impressions of a freshman; but "the street" in 1868 had little of its present complexity. Dean today of all the merchants, George W. Rand had arrived in December, 1865, which is close after the Civil War; and long may he continue. Deacon Downing came soon after and was genially presiding over a little pharmacy in a wooden building about where Storrs' bookstore is now. Fruit was one of the scarcest articles in Hanover, and upon the Deacon's counter stood a wire basket of attractive apples a penny each, or, if you did not pick the largest, six for five cents. Newton S. Huntington was carrying, on a savings bank which had been started by Elder Richardson and was doing some general banking business. The Frarys and their ever to be remembered tavern held important place in the community. In Cobb's general store you could buy anything, if Mr. Cobb, who did not like to be bothered, or his clerk, could find it. Clough & Storrs ran another general store. Later E. P. Storrs, long one of Hanover's most respected citizens, took over the Dartmouth Bookstore from N. A. McClary and carried it on for many years. E. D. Carpenter made good clothes, and Ballou, a dashing young blade, helped him. "Bill" Gibbs also tailored. I cannot recall that metropolitan houses had yet discovered that Dartmouth students had money to spend. How could they when two-thirds or more of them were teaching school 12 weeks in the winter at from $40. to $60. a month paying board, and at $25. and upwards "boarding around." ? Parker had the bookstore, and Major Wainwright the tin shop, for' there wasn't much plumbing. M. M. Amaral came about this time, though the invention of Para Caspa was yet to come. P. H. Whitcomb ran the printing office, and it was believed around college that the correction of an error in proof resulted in two errors in the revise. On press days Whitcomb used man power and it was also reputed that the long and lank John Suse was the only man in Hanver strong enough to furnish it. Smith's bakery had been in Hanover many years, and Smith, it is said, first brought anthracite coal into Hanover. It was H. O. Bly who took the pictures, and as business was not always pressing he was closely associated with a pipe and a bench outside his door. Dr. James Newton, in the Phi Gamma Delta House, pulled and replaced teeth; and his parlor was a center of amateur music, although in that respect there was no connection between vocation and avocation. Of course Ira Allen supplied the equine transportation. Once, summoned from the street to witness a legal paper, I visited the chaotic lair of Squire Duncan, over Cobb's store. He was then ancient beyond my youthful comprehension. I knew him much better ten years later.

I must give a special paragraph to Jason Dudley, whose era was from 1812 to 1893.

In his early days he was chief engineer of a stage coach and once drove my father into Hanover. At a later time my father recalled it and complimented Jason on the safe completion of the journey, to which Jason responded "You never said a truer thing in any of your sermons than that".

His real joy he found in his chosen profession, — driver of the Hanover hearse — of which he took the broadest view. One of Hanover's brilliant daughters, Mildred Crosby Lindsay, has given me some of her recollections. Mrs. Lindsay writes, "I think all names but the Crosbys should be suppressed. No Crosby was ever sensitive about a good story." And reluctantly I accept her judgment, — for the most part. Mrs. Edwards, in the cemetery arranging ing for the interment of her aged aunt, Mrs. Johns, said "I think, Mr. Dudley, that by placing auntie's head this way by uncle's feet you could make room for her and for a small headstone." "Well, Miss Edwards, this aint no sardine packin' factory, and while I am the head of this cem'tery heads will match heads or the old woman wont be planted", replied Jason, and the matter was settled.

And Mrs. Edwards in eulogy of the uncle, the elegant Professor Johns declared "It was a great loss to the college and the village when he paid the debt to nature." "Well, I swan" roared Jason, "if he paid the debt to nature it was the fust debt he ever paid; old Duncan never could see how he kept out of jail."

Meeting one day the healthy collector of these sayings, who has survived him many years, he said cheerfully, "I done some measuring down to your lot today and if we bury you in the north corner of the lot in the curve where we calculated to, your legs will be part in the highway. We was lottin' on your bein' short like your mother, but you got one of those figgers that nothin' stops your waist but your heels."

He said deacon Jacobs was considerable of a jellyfish with the ladies. He added that he understood there was something on his tombstone about his thinking more about God than he did about his food. "By gorry, the man that wrote that never see the deacon eat good victuals", was his emphatic comment.

When elder Charles, a paralytic, died Jason said "We all ought to jine in singing 'Thou art gone to the grave, but we will not deplore thee !' "

Reflecting upon the effect of a great granite stone placed over the grave of Dr. Asa Crosby, he said to Mrs. Lindsay's father, Dr. Ben Crosby, "Asa will be some late for the Resurrection, and it is a pity for he is the one Crosby you can count on gittin' in."

Dr. Ben Crosby, a noted after-dinner speaker, much younger than Jason, once introduced him at the Century Club in New York as a prince of story tellers and his own greatly feared rival. When Jason rose to respond he relieved the doctor's fears thus, — "Don't be a mite scared, Ben; dog don't eat puppy in the class I've travelled with."

There must be a limit to the space that can be given to this quaint person. Said he, "I never seed your grandmother consarned mad but jest twice; once when they was rowin' about the bridge and arrested the old doctor and put him in jail over at Woodstock; and he sent a man clear over from Woodstock to break it gently to his grass-widder. And the man said, 'Don't be askin' for your husband, Mum, for they have jailed the old fool in Woodstock, and as far as I am concerned I hope the old New Hampshire idiot will stay there'; and the other time was when she got all ready for a big family funeral, cakes, mince pies, ham, calves' head soups, &c., and I myself had fetched the coffin stands up and she met me at the door, mad clear through; 'Mr. Dudley', says she, 'there will be no funeral; the corpse has rallied.' "

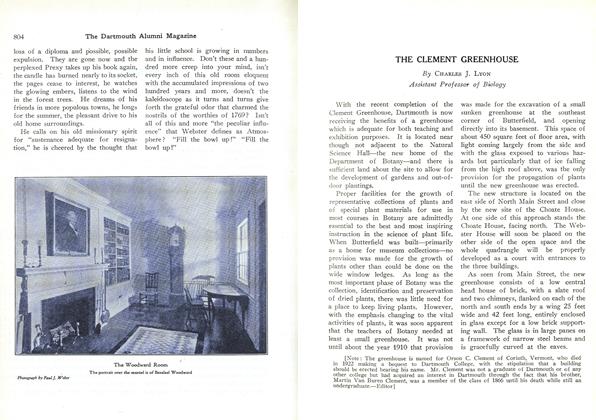

PRESIDENT BROWN'S HOUSE, N. W. CORNER OF MAIN AND WHEELOCK SIS.

MAIN ST., EAST SIDE, LOOKING NORTH

MAIN ST., WEST SIDE, LOOKING NORTH

SOUTH HALL

JANUARY 4, 1887. DARTMOUTH HOTEL IN RUINS. THE TONTINE IN FLAMES

MAIN ST., LOOKING SOUTH. COBB'S STORE ON THE RIGH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhat does a man lose by going to college ?

February 1921 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleTHE LOG OF THE DARTMOUTH OUTING CLUB

February 1921 By LELAND GRIGGS '02 -

Sports

SportsHOCKEY

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH PIONEER

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleSANFORD HENRY STEELE

February 1921 By LEMUEL SPENCER HASTINGS '70