The question has often been raised, chiefly by those who spoke without the advantage of personal college experiences, in years gone by. That the answer has been that one lost nothing by contrast with what was gained must be evident, since the increase in the numbers of young people of both sexes seeking collegiate training has been so monumental. The manifest conclusion of man- kind in general, so far a.s this country goes, is that the benefit far outweighs the various costs and forfeitures involved.

Nevertheless one finds now and then a dissentient voice; and not many weeks ago one was raised in the columns of the popular weekly magazine, the SaturdayEvening Post. The writer,"looking back on his own college course, was inclined to believe that he had wasted four years, spent much money, learned nothing to the purpose, and might much better have remained away.

Now it is impossible for any one to claim that this is never a just estimate in an individual case, for the instances in which men do go through college with no greater result than that outlined must be fairly numerous. All one may say is that the general verdict of the times is quite the other way and that very probably men cannot always trust their own judgments, even as to the effects of college on themselves, when it comes to striking the final balance. So many conflicting imponderables enter in. The man who has learned least in his four years has at all events enjoyed four years of constant contact with what it is no exaggeration to regard as the pick of his fellows, in an atmosphere which is in some degree sure to be intellectually stimulating. What one carries away includes much that is intangible and much that very probably one does not consciously recognize.

It is easy to see that one has certainly spent four years in unremunerative study, when one might have been at work for gain. It is also easy to figure the actual expenditure which those years have entailed, and measure it with reference to what one might have earned. It is not difficult to regard this as a positive loss. When one turns to estimate the offsets - such as the actual learning one obtained in exchange for the outlay of time and money — it is not hard to minimize the latter and conclude that the balance falls on quite the wrong side. "What did I really learn in college? Nothing!"

Fortunately, that is most probably a gross injustice done by a man to himself. It is undoubted that if a college graduate were to sit down after even five years to a literal examination of his academic recollections he could not pass with credit it - if he passed at all. One suspects that it is the sudden realization of the fact which prompts pessimistic conclusions like those reached by the writer in the Saturday Evening Post. Mr. Arthur Train in a book which had vogue some years ago ("The Goldfish") depicted a successful New York lawyer who discovered that he was hopelessly lacking in certain detailed information as to the history of ,the workl — did not know the date of the Battle of Tours, for example, or of Shakespeare's death, or of the Norman Conquest, or of Magna Charta. All those things he had known at some time, having studied in and graduated from college. But retain the facts he did not; and therefore he presumed himself to be ignorant. Yet it is safe to say that not one educated person in five hundred could have done any better than he. In fact it was a pleasant parlor pastime, for a space, to take Mr. Train's random questions and see which and how many of them could be answered in an intelligent company. It is a very unusual thing for any one to be sure of more than two or three such matters as those cited — save such, of course, as specialize in, or are teachers of, those very subjects. But is it fair ground for saying that one's study of history has been vain because one is not a walking encyclopaedia of dates ? Has one thrown away four years because at the age of 40 one has only the dimmest idea of what is meant by the binomial theorem ?

The benefits of college training are simply too diffuse and indeterminate to be measured satisfactorily by finite means. One mistakes the scaffolding of education for the finished structure. For every man who loses more than he gains by going to college, it is safe to say that a thousand gain more than they lose. The unsafe thing is to say how many of the thousand recognize the fact.

The alumnus now in middle life has no difficulty in recalling the time when a college president was traditionally a cleric, occupying his position in the educational world solely because of his superior erudition in classical lines. The first sensational break with that tradition was probably the choice of a trained manufacturing chemist, then only 35 years of age, to become president of Harvard. Harvard herself had probably no realizing sense that this step was one which in due season would be all but universally emulated; and no doubt to a very great number of her own alumni the selection of a youthful scientist instead of some ripe scholastic from the parsonage came as a shock.

In 1869, when Dr. Eliot entered upon his long career as an authoritative educator, there was comparatively little indication in the various colleges of the fact that the president's post was primarily administrative, and none at all of the fact that within the next half century the tasks of university management were to become as complex as those of any other great business. A college in those days was still a sort of exaggerated school, resorted to by a few men who contemplated chiefly the professions of teaching and the ministry, when not destined for the bar. Half a dozen professors of ancient learning sufficed to compose the faculty. Deficits had not become the fashion. Growth and expansion were not attained, even if regarded as desirable. The president of the college was likely to be an active member of the teaching force. As for endowments, they were meagre in proportion to the physical plants concerned. Custom led one to look to the head of every college for spiritual, as well as merely educational, leadership.

This has so completely changed that it is no longer possible of misconception. Yet the paradoxical fact remains that the choice of a president for any one of the 30 colleges just now seeking new heads is the more difficult in proportion as the field from which selection may be made has broadened. When one sought among the eminent few of a denominational clergy, the choice was usually simple and was frequently obvious. Now that the presidency of a large college demands faculties combining those of an astute business manager with those of a tactful diplomat, instances of the obvious choice are almost unknown.

It is in part due to the natural consequence of the enlarged recognition of sciences as appropriate topics for the college curriculum. In the early and middle periods of Dartmouth's own history, science as we now use the term commanded probably less of enthusiasm on the part of the learned men in the faculty than of dread and apprehension. One must remember that the gentle clergymen of that day had a wholesome fear of the scientific sceptics and their possible ill effects on the religious tendency of the day. The college portals, so far as the recognition of scientists was concerned, were more likely to be marked "V aderetro Sathanas" than "Salve." In short, the academic field was the church's domain — not the world's; and the world was keenly understood to be hostile with its new ideas about evolution and such like gear. All of which sufficed to make more interestingly distinct the difference between the presidencies of the late Dr. Bartlett and of Dr. Tucker at Dartmouth — the one a theologian of the old school, the other a progressive exponent of the new, though a clergyman still.

Nothing more illuminating on this point has been written than Dr. Tucker's own book, "My Generation," in which the task of the times following 1859 has been so cogently set forth. The reconciliation between old and new—welcoming science as the friend of God's truth instead of repelling it as a foe — formed the work to which the new president set his hand. The conspicuous efficiency with which it has been accomplished and the nobility of the result need no encomium before a Dartmouth gathering. It is probable, however, that with this extraordinarly smooth and successful transition there passed away forever the idea of a clerical presidency in Dartmouth. Science had come to the throne. And while her assaults on what were once regarded as the very foundations of religion had produced no more than superficial changes, the broadening of the educational field simply destroyed the original inevitability of the pulpit as the training-school of the professor. Faculty and president were formerly clergymen because it was natural they should be ; they are seldom or never so today because it is natural they should not be.

Just how free and open should be the hospitality of the mind ? One is forever being cautioned against intellectual snobbery of the sort which denies acquaintanceship with new ideas until the same have been properly introduced by recognized respectability — and one admits a certain fitness in the caution, since snobbery is never a pleasant thing. Is there, however, no compensating danger in the opposite course — that of rushing to embrace each new hatch'd unfledged comrade ? One detects in certain of our ultramodern educators what may well seem an unseemly readiness to break bread with unpromising strangers—chiefly of an immigrant appearance and with odd Russian names, which latter one suspects of forming part of the lure.

That one should always consider with respect a new idea which has at least a prima facie recommendation about it is no doubt a sound doctrine. That one should approach every new notion, whether social, economic, educational, or industrial, with a predisposition to find it truth because it is new, is hardly to be approved. Mere novelty and strangeness are not in themselves proper evidence of truth, any more than they are the necessary earmarks of a lie. The fact that a new postulate shocks us does not inevitably prove it to be a sound postulate. And yet one finds growing into menacing proportions a cult of educators who would fain have us believe that any novel doctrine which shocks by its novelty is probably right — the more so because established custom reacts so vigorously against it. The more shocking the innovation, the greater the probability of its verity!

What masquerades as the open mind is usually not open at all, but tight-shut. It is just as possible to be a bigoted devotee of radicalism as it is ,to be a blind devotee of reaction. The genuinely open mind is the blind devotee of neither. What chiefly irritates is the smug assumption of virtue, whether by those who want all things kept as they are, or by those who want everything altered. A new theory is possibly right—not probably right because it is new. An old theory is possibly wrong—not probably wrong because it is old. And the truly open mind is that which calmly weighs the matter without prejudice, for or against. Academic freedom, as Dr. Tucker somewhere remarks, cannot be divorced from academic responsibility. In Mr. Hamilton Gibson's very admirable and useful summary of the college history in pamphlet form one will discover on the closing page an interesting table showing (the increases made from time to time in the tuition fee charged at Dartmouth, from 68 shillings in 1770 to $200 in 1919—which latter figure has now been increased to $250. If one may estimate the original shillings as figuring 20 to the pound and may rate the pound at its usual figure of $5, there was but little change during the first 30 years of the college's existence. In 1795 the rate was, however, expressed at "$16 and contingent fee $0.80," which may not have been far from the 100 shillings previously charged as a practical matter, although it might at first sight appear to be an actual reduction. If reduction it was, it was the only instance in the annals. The trend from 1795 to the present day has been steadily upward, as was natural considering the constant growth in the scope of education and the widening realm to be covered by courses leading to baccalaureate degrees. Not to specify too minutely, the successive steps have been to $20, $28, $30, $.36, $42, $51, $80, $90, $100, $125, $140, $200 and finally $250.

It is manifest at once that the last two increases have been the most marked, being respectively an advance of $60 over the previous figure in 1919, and of $50 over the previous amount in the present year. The $250 rate is exactly double the tuition fee charged in 1909 et seq. In the middle years no such arresting change was made, the advances being only a few dollars at a time, with the sole exception of the notable advance of nearly $30 which was decreed in 1867 (just following the Civil War). The record somehow suggests the auctioneer's bids — save for the fact that instead of tapering down in size as the limit is reached, the tuition fee has taken that occasion to make its longest jumps.

Speaking of the new figure positively, it is admittedly high by contrast with what many others charge—yet is by no means yet equal to the actual expense of tuition which falls upon the college. In other words., even at $250 a year a man does not pay what the tuition costs those who provide it. The increase is therefore entirely justified from that view and indeed could have been further increased without wiping out the argument. The objections, so far as any exist, relate to its effect upon the student rather than to its abstract justice from the viewpoint of sheer business.

It may be argued, and it may be the fact, that to set so high a figure for college bills, no matter if it still falls short of meeting the cost, discourages a worthy class of students and directly encourages a less desirable one. This, however, may be met in part by the creation of genuinely remunerative scholarships which will either cover the tuition item entirely, or come so near to doing this that no hardship will be involved. Moreover in current circumstances, with the college forced annually to turn away applicants by the hundreds, it is practically imperative to do some such thing as this. Nevertheless one feels a certain inward reluctance, despite the fact that college deficits fall in the end upon the alumni and constitute a problem which it is desirable to make less pressing.

Tuition fees may some day recede — but it is noteworthy that our history holds no example of this and that current conditions give no sign of an impending probability. The cost of living may fall very appreciably without thereby making the tuition charge even as it now stands an excessive one. It is to be expected, then, that this figure will remain undiminished; and it is to be hoped that it need not be further increased.

The College not being engaged in a business for profit it is somewheat easier for it to reflect the decline in the cost of living than it would be for a mercantile establishment. Meagre as the declinations in the prices of necessaries have been, they have at least sufficed to warrant a curtailment in the cost of board in the College Commons as charged to the freshman class; and as a result the College may be said to be taking the lead in practical deflation.

Alumni readers of the MAGAZINE are invited to be free with expressions of opinion concerning topics touched upon in the successive issues, by correspondence with the editorial management. Only by the maintenance of a fresh and vivid interest in the current affairs of the college can the alumni body retain its appropriate place in that triune entity which we call Dartmouth—an entity made up of the students, the faculty and trustees, and the alumni.

It it our belief that of these three components the alumni body, besides being the most numerous one and the constant source of reliance for financial support, can be most vitally important to the upkeep and advancement of the institution. It is most desirable, therefore, that the alumni body keep itself duly informed of what goes on in Hanover, exercise to the full its prerogative of discussing matters which cannot fail of being interesting to real lovers of Dartmouth, and thus make the "Fellowship of Dartmouth Men" something more than a mere occasional abstraction. Perhaps there is in this something akin to the plea for making religion a matter of everyday exercise rather than the incident of a Sunday alone.

From the day when a man matriculates as a freshman until the day when he dies, he is a Dartmouth man — an integral part of what we call so elastically the College," whether his residence be near or far. As such, each has his clear right to opinions touching the affairs of the corporation—and his most effective way of making such opinions known may well be through communications to the magazine which is conducted in the Alumni interest.

This privilege of communication has been, and is being, largely availed of, to the pleasure and profit of the editors and beyond doubt also to the profit of the college. It argues a realizing sense of the intimate kinship between the oldest in our graduate body and the college that now is. The college of today is different in many ways from the college which we knew, say 25 or 50 years ago. But it remains our college, with its soul and spirit essentially unaltered — and the aim of the great body of its alumni should be to keep that soul and spirit essentially inalterable. We are in it, and of it. Those who must set a watch lest the old traditions fail are by no means confined to the students in college at a given moment, nor even to the faculty and trustees presently engaged in actual conduct of the college affairs. The alumni body must bear its part. An army of coldly indifferent graduates, concerned for the college only once in five years on the occasion of a class reunion, would be fatal; but very fortunately no such inertness, or decay of family feeling, is in prospect.

The point we are laboring is that the alumni may be of direct and positive assistance by the frank expression of counsel when anything comes up which prompts discussion. Of course in the last analysis the conduct of the college business must vest absolutely in the president and trustees, who form the directorate. But this conduct is bound to be the wiser, and those who control it will be the more heartened, if they can be favored with expressions of intelligent alumni opinion and assured by visible signs of the constant and growing interest throughout the Fellowship. The crowning mistake is that of assuming one's active college affiliations to have terminated with the acquisition of a sheepskin. If they have altered by that process it is only in the line of amplification. One is at last a member in good and regular standing—and from this allegiance there is no escape. "When I was in college," qUotha! Say rather, "When I was in college I was not really in college; I was preparing myself for a lifelong fellowship—and whether or not I should be found worthy of that fellowship was determined only at my Commencement day." Possibly this is is why it is called Commencement!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

February 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT, '72 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleTHE LOG OF THE DARTMOUTH OUTING CLUB

February 1921 By LELAND GRIGGS '02 -

Sports

SportsHOCKEY

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH PIONEER

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleSANFORD HENRY STEELE

February 1921 By LEMUEL SPENCER HASTINGS '70

Article

-

Article

Article$568,000 Alumni Fund

July 1951 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards

June • 1988 -

Article

ArticleWe Asked 100 Students: Who Would Make a Good Montgomery Fellow?

MAY 1996 -

Article

ArticleGREEN JOTTINGS

JANUARY 1964 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

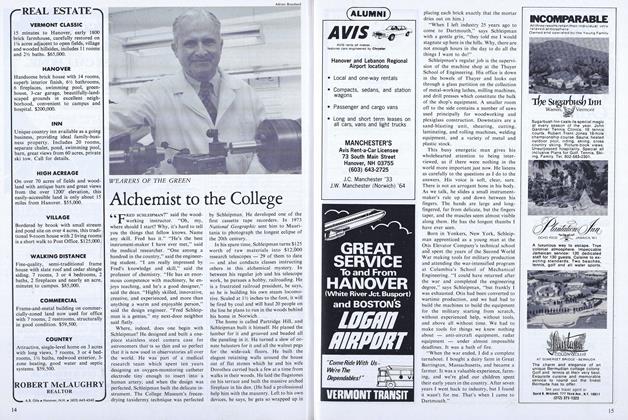

ArticleAlchemist to the College

APRIL 1978 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

May 1955 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29