(From "John Ball the Seer" by D. W. Tower in THE MICHIGAN TRADESMAN, December, 1920.)

From its earliest days Dartmouth has sent out into the world great pioneers, men with vision and purpose who have pushed forward frontiers of Geography and thought. One of the most interesting of the Dartmouth pioneers who went West in advance of civilization was John Ball of the class of 1820, who took a prominent part in the opening up of what was then known as "Missouri Territory," and now comprises the states of Washington and Oregon. The story of his trip is told by Daniel Webster Tower in the December, 1920 issue of The Michigan Tradesman.

The famous Lewis and Clark expedition sent out by Thomas Jefferson returned to the East in 1807. Among the men who had made the journey through the vast western wilderness was a sergeant John Ordway, of New Hampshire, whose stories of the expedition fired Ball with a determination to see the new territory for himself. The opportunity to gratify this desire came in 1832 when Nathaniel J. Wyeth induced twenty-three young and vigorous New England men to join the Pacific Trading Company and place themselves under his leadership with the avowed intention of being the first party of white men to follow in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark. After several months of preparation Wyeth sailed from Boston, March 11, 1832, for Baltimore, where John Ball joined the party.

Mr. Tower, in writing his article was able to follow closely Mr. Ball's original diary, and his portfolio maps, these, with several of Mr. Ball's letters written on the trip having come into his possession. In part his story is as follows:

Captain Wyeth had invented a combined boat and wagon box for use in crossing the rivers and plains of the West.

On arrival at' St. Louis, to their great consternation, they found that these expensive wagon boats were pronounced by experienced frontiersmen as impractical, so they were sold for half their cost. This setback somewhat impaired their confidence in Captain Wyeth's judgment.

Putting their goods on a small steamboat they proceeded up the Missouri River as far as Independence, Mo., the last white settlement on the route to Oregon.

At Independence they fell in with a parly of sixty-two experienced hunters and trappers under the command of William Sublette, who, seeing their ignorance and lack of proper equipment for the journey, kindly consented to take Wyeth's party "under his wing.'

Before leaving, two of their companions quit and returned East, having lost their enthusiasm by their first encounter with the wild life of the plains.

After many hardships, when only 400 miles from the Pacific, and after traveling nearly 4,000 miles from their starting point, the party was further reduced in numbers by the desertion of several of the original Wyeth expedition. Capt. Nathaniel Wyeth with eleven men, among them John Ball, placed themselves under Milton Sublette, brother of William Sublette, who, having received the furs secured by his trappers, returned to St. Louis, taking with him the remainder of the party from New England.

Milton Sublette accompanied the Wyeth party of eleven men only 100 miles, when they were left to find their way as best they could to the Columbia River and thence to the Pacific.

The ending of their journey is told as follows an Ball's diary:

"Oct. 29: Temp. 55. S. E. wind. Rain. Arrive Ft. Vancouver. Located on right side of river, 100 miles from ocean. Well received by gentlemen of company (Hudson Bay Co. factors), notwithstanding the awkward and somewhat suspicious circumstances in which we appeared."

Captain Wyeth soon saw that all their hardship availed them nothing and that it would be impossible for their little band to establish a trading post in competition with the highly organized Hudson Bay Co.

This fact was forcibly impressed upon him when he learned that the ship from Boston with their supplies had been wrecked in the Society Islands. He therefore returned East and later on brought back another party to Oregon.

Mr. Ball was restless and anxious to see the Pacific Ocean, so only tarrying five days at Ft. Vancouver, he started with four others in a canoe to descend the great Columbia River. His notes continue:

"Nov. 3. Tem. 55. Wind N. W. Clear. Five of us go down river in Indian canoe. Country continuing low on both sides. Pass the mouth of the Willamette, three miles below Vancouver. Mount Hood in rear. St. Helen to right, appearing a hexagonal cone, truncated, white and beautiful.

"Nov. 5: Tem. 55. Wind East.. Cloudy. Company sloop continue down River, which is white with swan and geese. Encamp on Tongue Point in sight of Fort George." (Astoria).

"Nov. 9: Tem. 55. Cloudy. Went across to Clatsop Point through rough sea. Encamped on East Side. Went three miles at low water round to the Point. Had full view of the rolling billows which I may some day pass with prosperous sails. Cape Disappointment bore N. W. the coast South St. Helens, East."

It would be well for present Oregon citizens, particularly of Portland, to pause a moment and try to enter into the spirit of John Ball's thoughts as he stood on that beach at sunset and watched the sun slowly sink into the Pacific Ocean, that washed the shores of distant Japan, which he had so longed to see. It is difficult for those who now find peaceful happy homes in Oregon to realize the emotions that must have filled the heart of that pioneer, eighty-eight years ago, when he first glimpsed the final goal of his ambition.

Leaving Boston, March 11, 1832, he, "with others, had endured over seven months of hardship and danger to bring into reality this supreme moment."

It was really a braver undertaking than that of Lewis and Clark, who were backed by all the military and material resources of our Government.

John Ball was born November 12, 1794, at Hebron, N. H. He died in Grand Rapids, February 5,. 1884, aged 89 years.

Practically all his years from 1836 were passed in Grand Rapids, where he was universally loved and esteemed. For thirty years he. was school director or moderator, as it was then called.

Of a very generous disposition he showed his love for the Valley City by leaving forty acres of natural wooded hills to the city for the public park which bears his name.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhat does a man lose by going to college ?

February 1921 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

February 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT, '72 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleTHE LOG OF THE DARTMOUTH OUTING CLUB

February 1921 By LELAND GRIGGS '02 -

Sports

SportsHOCKEY

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleSANFORD HENRY STEELE

February 1921 By LEMUEL SPENCER HASTINGS '70

Article

-

Article

ArticleIncomes of Ten Year Alumni

June, 1911 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

August, 1923 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

MAY 1963 By GEORGE DROWNE D'33 -

Article

ArticleLord and Lady Dartmouth Will Attend 1969 Commencement

JANUARY 1969 By GOVERNOR ROCKEFELLER AND KINGMAN BREWSTER TO SPEAK -

Article

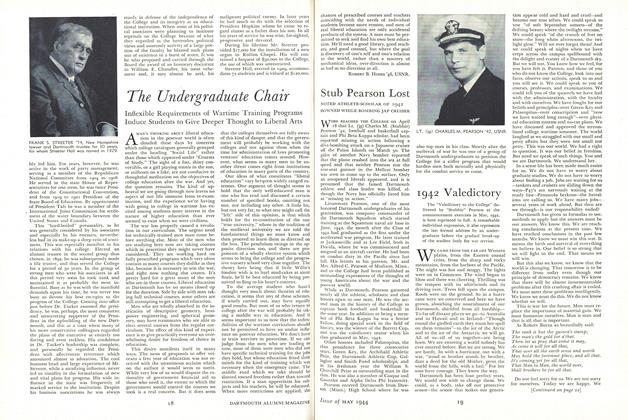

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR -

Article

ArticleSHORT PAGES FROM ONE LONG LIFE

January, 1926 By Roy Brackett