behind its proper point at this season, measuring by previous years. It should not be. The need.of this fund is not less than in former years. It is greater. Unless it can be maintained at the figure consonant with efficiency the college must go backward at the moment when everything points forward.

To a great extent we believe the present laggard quality of the subscriptions is due to procrastination only—to a mere omission to carry out a perfectly well-formed intent. This, however, is a very serious matter in that it acts as a discouragement and deterrent upon the class agents whose efforts are required to be made more and more strenuous, and whose service becomes more and more irksome in proportion thereto. May the MAGAZINE venture a word of urgence in this regard?

The duty performed by the class agents in collecting the class quotas is a thankless one, demanding at the very best an amount of time and energy which busy men can ill spare from their personal concerns. It isn't fair to make this duty any harder for them than it naturally is —and yet it is quite probable that through mere indifference most of us do thus make it harder. . But if this thing has got to be done!—and it certainly has —it is of no benefit to keep putting it off. That much abused slogan, "Do it now," is clearly applicable.

We raise this fund every year to represent the interest upon an endowment which we have not raised and in current conditions could not easily raise. It is less burdensome to turn in the equivalent of the interest, and thus make the lack of endowment unimportant for the moment. The size of the fund is not excessive, even if it exceeds the quota set. At its maximum it is no more than we can well raise—no more than other colleges raise. None of us grudges it, of course; but we are all inclined to wait until tomorrow before writing our cheques. That's why the fund is behind time this year; but if every reader of these lines who has not yet sent in his intended contribution will do so immediately, the fund will be ahead of schedule, instead of behind, by the end of the week.

Professor Andre Morize of Harvard university, widely known as a gallant French officer during the war and no less appreciated as a cultured and discerning French teacher in times of peace, delivered recently at Cambridge an address in which he gave his impressions as a Frenchman of the American educational system. This address was reprinted in full in the Harvard AlumniBulletin in its issue of April 6—a distinct service to the educational cause. The urbane observer from France finds much to praise, some things to envy, and not a little to criticize in the American educational plan—making due allowances always for his own different training and inherited prejudices. It is probable that most Americans,, reading or hearing what he has to say of our teaching system, will quite generally concur in holding that where Professor Morize criticizes us his Criticism is just.

Naturally the first thing to strike him has been our lack of centralization and diversity of standards. This is probably an inevitable consequence of the country's territorial extent. The closely knit and highly centralized educational system of France is not possible in a country covering so vast an area as our own; and the present estate of American poli tics makes it of dubious utility to nationalize the control of all public schools in the hands of any Washington bureaucrat comparable to the French Minister of Public Instruction. The advantages of the French system, however, are obvious. A pupil leaving the schools of Marseilles, for example, and removing with his parents to Lille, would find the pupils of the school to which he went in the latter city in precisely the same spot, educationally speaking, and the methods exactly the same as those in the school which he had just left. "Sire," once said a French minister to the monarch of his day, "At three o'clock this afternoon every school-child in France will be translating a page of Julius Caesar." This, while not literally true of the French system today, is not far off the facts.

Professor Morize is likewise impressed by the fact that we make no very definite standard for our collegiate degrees. One who devotes a specified number of "hours" to a variety of available studies is in due course admitted to the baccalaureate fellowship. In older countries the A.B. degree implies that its holder has been through a specified course, common to all possessors of that degree. The American system strikes Professor Morize as much like "adding together four sheep, five locomotives and two umbrellas"—i. e., adding up all sorts of dissimilar things and calling the result an A.B. degree, if only the desired number of "hours" can be shown to have been passed in study.

With much pertinence and good humor the critic acknowledges that European education would be better for a dash of American progressiveness—while implying also that American education would possibly be better for a dash of European conservatism. As we see it this is undoubtedly true. But it needs always to be remembered that each system has sprung up in response to the local needs, as they appear to local instructors. The educational product of America is bound to differ from that of France, or Germany, in much the same degree that vegetation does.

In decrying the American propensity to exalt mere marks, and the lately increasing tendency to regard pedagogical systems as ends in themselves, rather than as means to ends, Professor Morize seems to be on firm ground. "As far as I have been able to judge," he says, "in all your schools written work is 'marked' rather than 'corrected/ for the reason that it is only the mark which is really important." Where the proportion of correct and incorrect answers determines the mark, or standing of the student, "a boy of almost no intelligence but gifted with an excellent memory, or a' lazy lad well tutored during a few critical days, as after all nearly as much chance of succeeding as—and often a better chance than-the active-minded, original, artislc young men endowed with a less ceram memory." At Dartmouth, especially in view of the new system of selective admissions based on extended records, this remark will be recognized as having a familiar sound.

The recent craze among technicians for psychological tests and for various methodological schemes "that have a scientific appearance," also seems to this critic to be sadly overdone, although he is too prudent to condemn them out of hand and altogether. "Tests, statistics, charts, standards of different kinds, are the fashion," he remarks; adding sagely, "Perhaps to pass, like all fashions!" He thinks confidence in these things may be exaggerated—a remark which many an American teacher, struggling with the modern mysteries of the "Intelligence Quotient" and with a growing burden of "paper work" to satisfy insatiable overseer's who are statistics-mad, will applaud most heartily. We are indeed in some danger of forgetting the main business of teaching (which is certainly to teach) in our zeal for making repeated blue-prints of the child-mind in various stages of supposed development. One is tempted to go beyond the criticisms of Professor Morize and affirm dogmatically that under our present school systems, as applied in secondary grades, teachers are forced to tabulate so much that they have far too little time for the arduous business of instructing.

When it comes to the colleges, the criticisms are largely of the familiar sort, including the query whether we do not, on the whole, once again overlook too much the business of learning in favor of various alluring side-issues. The value of the latter—such as college organizations and athletics—is not denied; but the question is raised whether the incidentals may not be receiving rather more than their just share of undergraduate attention,. Here allowance must be made for the French inheritance, since in the European view there is nothing in common between the process of being educated and the processes of having fun. Professor Morize candidly admits that a moderate amount of pleasurable adjuncts would have improved the educational system in which he himself was trained; but he is quite sure that, among us, "sports and athletics enjoy a position of esteem and dignity not held by study and success in scholarship." It cannot be successfully denied. To this defect, one fears, the public press, aided by its correspondents in the colleges, contributes not a little. And the sequel is the lately-born effort on the part of New England college presidents to limit the already swollen expenditures of various athletic and other organizations, which seem to be in danger of totally eclipsing the fact that first and foremost a college education is intended to educate young men, rather than provide for them a sort of overgrown combination of athletic and country club.

Closing the article by this eminent and always agreeable Frenchman, one feels that he has with a peculiarly skillful hand indicated the defects of our qualities—being by no means indifferent to the latter. There is much to be emulated, he believes, in the intensely practical aim of American educators; yet "we are not yet ready for the day when the Sorbonne and the College de France will have professorships of 'laundry management,' of 'tea-room management,' or of 'ice-cream making. ' " That is the nearest approach of the writer to thrusting with unbuttoned foil—and the satire of it is sufficiently delicious to deprive the thrust of any sting.

America must no doubt create her own educational cosmogony and make it suitable to her peculiar necessities, which latter will be different from Europe's in many ways. That much which is now prominent in the educational process will be abandoned in favor of something else —whether new or old—is probable, if not actually certain. Many of the newer things are likely to prove worthless after being tried. It is already clear that in some directions the pedagogy now so fashionable trends toward manifest excess and absurdity. To have these able and amiable gentlemen from abroad, who enjoy a perspective not possible to us who have been on the ground all our lives, tell us how the American school system strikes them is helpful indeed. In which connection, mention should be made of the fact that views not greatly dissimilar have likewise been published of late by Professor Feuillerat, French exchange professor at Yale.

That laughing philosopher, Professor Stephen. Leacock of McGill University - and incidentally of our own honorary fellowship—is byway of speaking many a true word in jest when he discusses in the recent issue of Harper's Magazine the relative merits of Oxford or Cambridge and those of colleges in Canada or America. With his customary lightness of satirical touch he points out certain elements of excellence in the venerable British universities which at present we have not here—and apparently do not even desire—at the same time indicating certain respects in which the colleges of America and the Dominion are tending toward a development of their own, which England would do well not to despise. The hint is that if we grossly overdo our worship of progress and efficiency in education (as no doubt we do), regard for those qualities is similarly underdone in England—or in France.

Speaking as we have been doing of the conclusions reached by Professor Morize, some reference to Mr. Leacock's article is not altogether inappropriate here. It is not that one side of the Atlantic quarrels with the other over the aims and scope of higher education, since it is probable that each country concerned is feeding its soul with the food convenient for it. England's university education deliberately aims at something quite different from what is aimed at here, but deemed most useful for and suitable to England. America certainly has not yet arrived at the point of appreciating as deeply as does England the beauty of a leisurely culture which only the few especially earnest and well qualified students may, or will, lay hold upon—the college meantime caring little what becomes of the rest. The comfortable old system of Oxford, with its dons who never teach, its lectures seldom or never delivered, and its tutors who develop scholarship in a few "by smoking at them" in Mr. Leacock's phrase, may not find much favor here; but it is not amiss to be reminded that the British results, so far as there are such, are most conspicuous.

What strikes us especially is the writers reminder that what was done ages ago for British universities by Henry VIII, Wolsey and others was in no essential respect different from what our modern oil and steel magnates are doing for us today. It is fashionable in some quarters to turn up an aristocratic or academic nose at the mention of modern munificence, chiefly because there have not elapsed as yet centuries enough to give to such benefactions the agreeable mustiness of age. However, as callow young men are wont to remind us when accused of their immaturity, this defect will in due season be outgrown.

Traditions {are things! without price and are thing's which cannot well be forced—certainly not created out of hand by a Carnegie, or a Rockefeller. Like Topsy, they just grow. Those who already possess them like to exult a little over such as must still tarry a while in Jericho till their beards be grown. The English gardener in the familiar story who, when approached by an American millionaire with a query as to how the English lawns were brought to their high state of perfection, replied "We cuts it and rolls it for six hundred years," may have intended a sneer or implied a reminder of American rawness in point of time—forgetting that once the greensward of Warwick was no older than that of our modern Gopher Prairie.

Our older colleges—and America is beginning to have some which are at least no longer in the flush of their first youth—are similarly prone to a bit of superiority in speaking of such as can boast only a brand new and highly endowed equipment without the mellowing graces of a century or two. Possibly we do not in fact disdain the new-born completeness of a university which has just sprung fully armed from the head of Zeus at the tap of some magnate's wand—but we commonly point out our greater reverence for "a past" and give ourselves a few airs over the fact that we have one. Age will atone for many a defect—and lack of age is the one thing that cannot be cured by money.

Wherefore let us, for our greater humility, reflect that there is certain to arise a generation to which the most lavish benefactions of the most blatant of our nouveaux riches will seem as remote, as legendary and as dignified as. those which created the most venerable endowments of European universities. Time was when Henry VIII and Wolsey and the rest had their contemporaries—who doubtless felt toward them much as the present day feels toward its inordinately wealthy folk, who probably spoke of them as predatory, and who regarded such gifts as mere ostentatious garishness. But give our oil, steel, pork and sugar endowments half a dozen centur ies in which to ripen ! That is what the others have had, and all one need do is sit down to wait! Time has given the world perspective enough for the needs of Oxford. It will do the same kindly service in due season for Chicago and Minnesota.

By the way, the University of Pisa is this year to observe the millennial anniversary of its founding; but with true Latin politeness it will doubtless not go out of its way to remind us that Pisa was old Pisa when Oxford was a pup.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

June 1922 -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

June 1922 -

Article

ArticleNEW LIGHT ON WEBSTER AND HIS SEVENTH OF MARCH SPEECH

June 1922 By HERBERT D. FOSTER '85 -

Books

BooksA Student's Philosophy of Religion

June 1922 By W. H. WOOD -

Sports

SportsTRACK

June 1922 -

Article

ArticleEXTRACT FROM RECORD OF TRUSTEES' MEETING

June 1922

Article

-

Article

ArticleWILLIAM GILLETTE

AUGUST 1930 -

Article

ArticleV-12 VALEDICTORIES

March 1945 -

Article

Article1981

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Emil Miskovsky -

Article

ArticlePartly Solved

June 1952 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleTuck School

November 1942 By G. W. W., A. W. F. -

Article

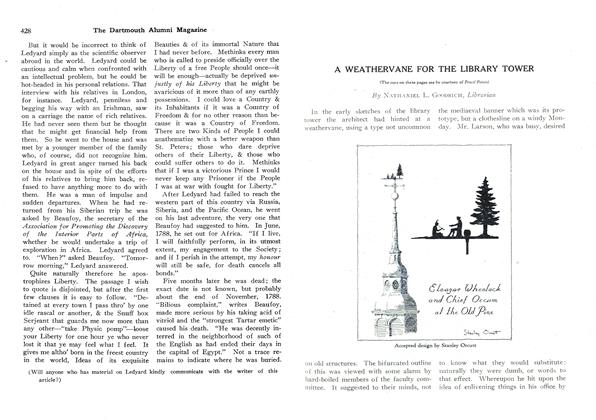

ArticleA WEATHERVANE FOR THE LIBRARY TOWER

MARCH, 1927 By Nathaniel L. Goodrich