of boreal cold which in older days gave Hanover an unenviable reputation, but which now atones by advertising the college in a curiously individual way. To those of us who were reared in the days that antedated the New Dartmouth, Hanover was not esteemed to be the ideal winter resort it has latterly become. One bore, with such fortitude as God gave one, the hardships of a climate where snow was plentiful and where a zero temperature was regarded as both mild and springlike. Records of anywhere from 35 to 40 below zero were not unheard of. Paths were commonly made by the insistent tread of the scholarly pedestrian, producing well-compacted ice which lingered into the jocund days of April. If one sang any songs of Hanover in winter, they had more to do with a "rouse by the fire" (pass the pipes, pass the bowl) than with excursions to rugged, remote and frozen mountains, or winter carnivals, or the perilous-seeming leap on skis from precipice to precipice, and so forth.

We have changed all that. Hanover in winter is Hanover at her best. The Outing Club, to be sure, knows no seasons and plays no favorites. It can always find something to do out of doors. But it is in the dead of our vigorous northern winter that it makes its outstanding appeal to the world, with its healthy insistence on the pleasures of a nipping and an eager air. Dartmouth, once the dolorous victim of winter, is now winter's favorite and joyful beneficiary. New Hampshire is America's Switzerland—why not Hanover, America's San Moritz?

Reference has been made with frequency in these pages to the excellent work of. the Outing Club—that comprehensive organization to which something more than half of the college belongs, and which does so many admirable works enhancing bodily health in the individual and spreading the fame of our cloister 011 the hill-girt plain. The Outing Club is at its best now, with the familiar hills wrapped in white, the air keen and sparkling, the mercury low in the tube. The once frequent boast of Dartmouth men was that their close grips with frozen nature somehow made them more virile than other folk—apparently because it led to piling high the air-tight stove with logs, which one hoped had been come by honestly; to sealing windows and doors hermetically; and to the omission of all but the sketchiest of personal ablutions because the water came frozen home i' the pail. Evil and brief was the pilgrimage between one's cozy tobacco-scented den and the half-arctic, half-tropical, spaces of the North Latin room. One suffered and was strong— in one's own conceit. That the day would come when all Hanover welcomed the icy breath of winter and went forth eagerly to make of it a joy and zest was hardly dreamed by any student of the late 80's.

The Outing Club has taught many things, but best of all the lesson that one's environment may always be turned to account, even in what might at first seem, and once did seem, stern conditions. It is the adjutant rather than the enemy of educational activity—a rare thing in college sport. It has probably done more than has any other one activity of the student body to revive and perpetuate ancient traditions peculiar to the life of the rigorous north. When you live in the north, do as the Norse do! Winter is the normal thing for' winter months—therefore do not attempt to live in them on a summertime basis! Adapt sport and dress alike to the surroundings! Get the good out of winter—rather than brood over the incidental discomforts. In short, be a man's man and not a stove-hugging, radiator-cuddling mollycoddle ! That, or something like it, is the underlying philosophy of the Outing Club at this season of the year.

If we emphasize this organization's claims to attention anew, it is chiefly because to many of us alumni it is a novelty which is as yet not sufficiently familiar. It has sprung into being and has grown to its present size with a series of years so brief in span that to the graduates of even IS years ago it is little more than a name. We read of it in newspapers and in magazines—there was, by the way, a very readable account in the January Outing (magazine) by Fred H. Harris, himself prominent in founding the club at Hanover, on his early experiences with skis as a means of winter sport, which has a distinct Dartmouth tang. But we don't yet really know the Outing Club as we ought to, despite frequent mention of its trails, its hospices on a chain of hills, its roastpig suppers on Moose Mountain, and more or less photographic exploitation. Perhaps the best way of all, as a first step, is to attend the winter carnival and see the more showy side of Hanover's winter activity.

This initial step might well be followed up by joining the club, as an alumnus-member, which is about to be the subject of an active campaign. Why not?,. There is no doubt that the facilities of the Outing Club could be made a matter of more general use and need not by any means be confined to the undergraduates. Those who are fond of summer explorations might very well make the pilgrimage from shelter to shelter over the increasingly popular trails that lead from Hanover northward, and thus make the Outing Club a direct personal concern, with mutual benefit to the alumni and to the organization.

Speaking generally, this is an age increasingly appreciative of life in the open —a very salutary thing in view of the other tendencies of our highly-developed civilization. Whatever conduces to the healthy enjoyment of primitive elements, such as sun and air, exercise and the contact with rugged nature, is surely worth our united and enthusiastic support.

The unprecedented increase in the size of Dartmouth college classes within the past dozen or fifteen years has had one curious result, which it is improbable many of the alumni have ever paused to consider, if indeed they are aware of it at all. It has shifted the "centre of gravity," so to speak, of the alumni body.

Down to the beginning of the growth which has been so remarkable—which is to say down to about 20 years ago— classes at Dartmouth had ranged about the same in magnitude year after year. As a result the center of gravity of the surviving alumni was always in virtually the same position. There were about so many older alumni and about so many younger ones. The total number of alumni remained reasonably constant. Those who had been out of college from 20 to 30 years constituted the most active membership and the center of gravity lay somewhere in their midst.

Since the early 1900's this has rapidly changed. The new classes have been four, five and six times the size of the classes commonly graduated in the middle and late '90's. As a result, the so-called "centre of gravity" in the alumni body now falls somewhere near the class of 1909; that is to say, fully half the present alumni body consists of men twelve years or less out of college. The other half includes men who have been out of college from thirteen years to something over 60; and in this latter half, naturally, the men who have been out of college less than 30 years far exceeds the number who have been out 30 years or more. Therefore the alumni body is, for the time being, a youthful organization in clear majority—a very different situation from what existed prior to the rise of the "New Dartmouth."

The controlling factor making for a static center of gravity, of course, is a reasonable constancy in the size of the classes. In the course of a decade or so the situation will doubtless change again—reverting to the more normal condition because the present lop-sidedness, due to a sudden increment in the more recent classes, will disappear. If there should supervene what in sporting circles would be called a slump, so that future classes shrank in size as sensationally as they have recently swollen, the tendency would be toward a retreating centre of gravity—perhaps to a point behind where it normally stood a quarter-century ago, the present large classes becoming in due course the more venerable, but still, despite the ravages of time, outnumbering their more youthful fellows. JNo one can foresee what the future has in store—but it is plain enough that the present condition produces a distinct alteration from what was true at the time, say, of President Hopkins' own graduation in 1901.

This is by no means intended as an intimation that the change is a detriment. It merely points out the fact that there has been a change. It is a change which very few, outside the actual administrators of college affairs, have yet recognized. Most of us still think of an average alumnus as a man in middle age, more or less matured by ripe experience, nearing his 50th year of life and his 30th reunion. But the average alumnus, as a matter of fact, is at this moment one who has but lately come back for his tenth reunion, and is looking upon the quindecennial as something almost too remote for detailed planning!

There is, or ought to be, a sobering thought in this for the younger men, in whose hands the destinies of the College already rest to a much greater extent than, was formerly the case. Alumni representation in the board of trustees is an established fact, and by means of it the alumni have their potent voice in the conduct of the College. This entails no light responsibility. "Old men for council; young men for war," was a saying which once had vogue and which has probably not outlived its usefulness, even in the modern day—a day in which im- patience seems unfortunately to be a regnant element. It is not too much to call attention here to the need of sanity and sobriety in this regard—striking the needful balance between the possible over-caution of age and the probable impetuosity of youth. Not without reason does one refer to the central point in the alumni body as a center of "gravity." Very happily, youth and levity are not necessarily and always synonymous terms—and certainly have not proved to be such in the constitution of Dartmouth. The essential gravity has been there and bids fair to continue. Mere politics cannot be said to have figured unduly in alumni matters, despite the fact that at present the preponderance of weight in graduate councils now falls this side of the class of fifteen years ago.

References in recent numbers of the MAGAZINE to the new system of selection to be employed in filling future freshman classes have perhaps not stressed as heavily as should be done the evident trend toward a higher standard of scholarship—a most desirable thing for the College, ' and one which many thoughtful friends of the institution have anxiously awaited. It is a distinctly important thing to select for the entering class the men who have indicated the possession of sufficient scholastic ability to maintain a stand in the first quarter of a preparatory school class. One who has succeeded in maintaining a position of that kind in a worthy school seems virtually sure of success in his application to be enrolled at Dartmouth. After that, selection depends upon certain other elements,—such as character, demonstrated capacity for leadership and geographical distribution—the latter especially desirable, and the other elements more readily susceptible to ascertainment than might at first appear.

That the standard of educational excellence ought to be higher than it has been, may be predicated of pretty nearly all colleges. Dartmouth is no exception and it .so happens that because of the pressure for admission, which now exceeds by so notable a figure the number who can be received, Dartmouth has a wholly unusual opportunity to take the step which has so long seemed desirable. To pick and choose, with an eye to admitting only those who will make the best use of the chance—why is not that the proper thing to do ?

American college education differs markedly from that in other and older countries. It is more nearly universal. It has a somewhat different aim. It is not altogether fair to put the present product of the American college against the product of Oxford or Cambridge, as a matter of purely cultural standards. Nevertheless there has long seemed to us to be a manifest need for making the ordinary academic degree—and perhaps the scientific degree as well—connote rather more of intellectual excellence than has been the case with the average American college in recent years. One may not ask too much; but one must ask enough.

Restoration of the Dartmouth-Harvard football game (for one year at least) marks an achievement which seems generally to be regarded as a return to normalcy. It is a restoration for which many have longed. The news of the 1922 schedule has been received with general gratification in which of course, Dartmouth men living in the vicinity of Boston have the preponderant share. Somehow the annual football contest at the Stadium seems a peculiarly appropriate one. Its abrogation was regretted. Its revival will be widely acclaimed.

Old traditions die extremely hard, and when the immortal Daniel once mentioned Dartmouth as "a little college" he uttered an expression which many still receive as accurately descriptive. The fact that Dartmouth is at present virtually of about the same size as Princeton in point of students, and well past her 150 th year as well, has not sufficed to amend the popular conception of the "Big Four."

Despite the meagre proportions of the older alumni, elsewhere referred to, there are plently of us living who can recall the day when the Harvard game was almost the first of the season and when the outcome was in no sense doubtful, save on the score of Harvard's total number of winning points. The sudden change, which made the college a prominent contender and which culminated in a brief series of contests in which Dartmouth either won or tied the score, put an entirely new aspect on the situation. The game suddenly advanced from the early and unimportant stages of the season to the very last date prior to the acknowledged "classic"—the game with Yale. That it was too stiff a game to come so close upon the Yale contest soon became apparent—and as a natural consequence the present renewal of relations includes a somewhat earlier date than was the rule when these games ceased to be played. But it is a reasonable compromise between playing the game too late and playing it early; and one hopes for a revival of the days when a fairly even battle could be looked for, with a healthy general interest in the contest to give it prestige. Dartmouth's task now is to prove herself a worthy contender in every way.

Once again, despite the shifted center of gravity elsewhere referred to, there remain alumni yet living who can recall when a football match at Hanover meant a contest between the two halves of the undergraduate body, two classes kicking the ball down the field against two classes trying to kick it back—that side winning which first got the ball across the line of fence at either end. More still can remember when a contest of any sort, apart from the events of the track, meant a purely college gathering, usually not a very overwhelming crowd, seated on the ground along the sidelines, or on a small improvised grandstand. But to most—since the majority of us have graduated since 1909—the modern meaning is more familiar; to wit, athletics on a grandiose scale, handling sums of money such as no student dreamed of a score of years ago, necessitating huge budgets,x a colossal permanent equipment, nation-wide travel. Is it a good thing?. Would it be for the general good to return to the bread-and-buttery days of our daddies? We are tempted to answer that, whether it would be a good thing or not, the chances at present are about a billion to one against it.

Revision downward there may be. It often seems as if there must be. The thing has got out of its sphere. College sports in the major institutions—more especially football, which has no professional counterpart—have come to be public shows, conducted on a prodigious scale and at enormous cost. That they are utterly out of harmony with the original ideas and ideals of college athletics will be denied by comparatively few. But people like it. The college boys like it. It has at least to some degree an advertising value—which appeals to college officers; and it suffices to fill the campaign chests for athletic managers all along the line—which appeals to the students in a special manner. On one big game, or on two big games, hang (so to speak) all the law and the profits.

Perhaps athletics ought not to need these vast "bowls" and "stadia," ought not to include trips to the far coasts, ought not to demand financing on this swollen scale. But they do in fact involve all those things, and we suspect that the protest against it would be drowned out by a roar of approval in any referendum to the college students and alumni of the United States. It is a condition and not a theory that confronts us. Abuses may be cut away—probably must be in time. But that there is as yet sufficient revolt against the idea of public spectacles to enable the speedy return to simpler notions is not borne out by any evidence which we have seen.

There lies before us a letter from a thoughtful alumnus who is convinced that "a clay of reckoning is coming." It is quite possible. He intimates that the advertising value of great intercollegiate matches is often exaggerated—and we incline to think it is so. But the cry as of old is for "the games"—which have become a sort of national institution, especially in the great cities; and the long established habit of doing such things lavishly will not be readily outgrown. In many ways we regret this overdevelopment—but we can see no prospect of any immediate change in the way of curtailment.

Through the Vale

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

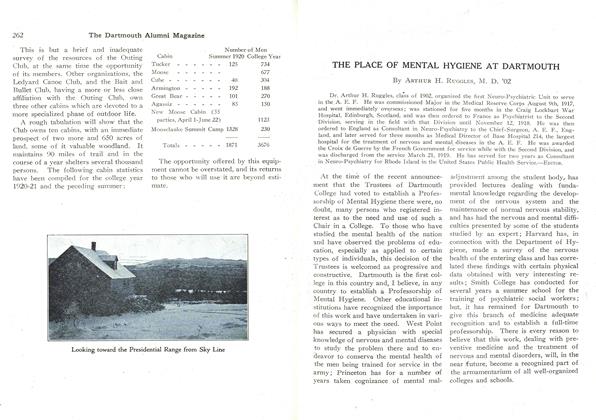

ArticleOUTING CLUB CABINS AND TRAILS

February 1922 By I EUGENE FRANCIS CLARK '01 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH OF THE FUTURE?

February 1922 By HARRY R. WELLMAN '07 -

Article

ArticleTHE PLACE OF MENTAL HYGIENE AT DARTMOUTH

February 1922 By ARTHUR H. RUGGLES, M. D. '02 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

February 1922 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

February 1922 By L.S H. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1906

February 1922 By Ralph Thompson

Article

-

Article

ArticleJUNIOR PROM WEEK

June, 1914 -

Article

ArticleRESEARCH GRANT TO DR. JUST '07

July 1920 -

Article

ArticleALSO FELLOWSHIPS IN BIOLOGICAL WORK

March, 1924 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ON TV

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF '79

June 1936 By Clifford Hayes Smith -

Article

ArticleClass Notes

Jan/Feb 2002 By Marrin Robinson '82