Perhaps more clearly than in any other newspaper which commented upon the matter the correspondence between President Hopkins and the Baptist committee of so-called "Fundamentalists" which took place last November and which was published, in February, was analysed by an editorial writer in the Manchester (N. H.) Union. The editorial is reprinted here.

Dartmouth's Quest

(From the Manchester (N.H.) Union)

Time was, and not so very long ago, when life's riddle was pretty satisfactorily solved. The Master of Arts was master of all the arts. What was to be known was known, and was in the books. What was to be believed was also in the books, and woe to him who doubted. And the little earth where this tidy closed system of ideas was held, was to be forever a very little earth, for was it not surrounded on all the maps by a terrifying terra incognita inhabited only by monsters calculated to strike terror into the heart of the boldest?

Then came the navigators, restless spirits who may or may not have been masters of all the arts but who did know something about handling themselves on shipboard, whose daily life was compact of problems and situations requiring practical solutions, whose curiosity was forever being stimulated, and whose conquest of real terrors took the edge from fear of imaginary ones. They were not mere sailors, of course. The best of them were thinkers, scientists, and they were educators. That is they "led forth" in a quest for what is true within their field of inquiry. And how they sailed through the monsters of the deep with which the schoolmen had crowded the fringes of their maps! They and their kind have been sailing on ever since.

And not only ,the navigators. , Others also inquired with minds at least part way open. The earth and the world opened out before them. We of today say that theirs was a truly educative period, when curiosity impelled to inquiry, and inquiry took account of facts, and facts once appealed to, rose up on all sides and simply toppled over any number of fanciful structures which, so long as they stood unchallenged, had embodied all human knowledge.

Now, as we read it, the reply of Dr. Hopkins of Dartmouth to Mr. Masse of the Baptist Fundamentalists is in effect that Dartmouth College is to stand with the navigators, and astronomers, and physicists, and humanists who are trying to get at what is true about this world rather than with the dogmatists who have got their answer to the enigma.

Dogmatists there are aplenty just now, not only sectarian, but also political, economic, and what not. And they are all out to get control of education. That is why this Hopkins-Masse correspondence is of interest to every public-minded man and woman in the state, and to a newspaper that cherishes the ideal of being of the life of the state. The teachings of a denomination or a group within a denomination may not concern us much. The effort of a group to control a sectarian college might be none of our business. But the studied propaganda of religious, political, industrial "crowds," aimed at college control and the petrifying of education so that instead of being a leading forth it shall be merely the handing out of formulae becomes a matter of personal concern to New Hampshire folk when Dartmouth, the undenominational liberal arts college which for more than a century and a half has been part of their social self, is one of the colleges that the propagandists are trying to capture and convert into a museum of embalmed ideas. Just now it is the Fundamentalists who are after it. That is, they are in the limelight. But they are not alone, and Dr. Hopkins' reply to Mr. Masse may well have been calculated to serve the purpose of an answer to the rest and a message of great joy to all whose ideal of the college is that of fearless inquiry, all the vital lessons of the past being utilized in the inquiry. The pith of the reply, one sweeping, far-reaching sentence, is this:

"The minute that education becomes something besides a sincere and open-minded search for the truth it has become a pernicious and demoralizing influence rather than an aid to society and an improver of civilization."

Education at Dartmouth, then, is education according to the meaning of the word, a leading forth, a quest under leadership, intellectual navigation, a search of what is true and of course, for the means, the methods, the processes to this end. To arouse curiosity and stimulate inquiry, to indicate blind alleys long since explored but also to push courageously into unexplored openings, and all of the while to add and to keep sharp the implements for cutting through life's thickets; to "prove all things" in order the more firmly to "hold fast that which is good," this, we take it is the idea of the Dartmouth group, and it is in just as sharp contrast with the educational theory of formulators of religious, political, economic closed systems as was the adventurous spirit of the men who specialized in navigation in contrast with that of the schoolmen who crowded the fringes of their little maps with pictures of frightful beasts that never were in time or space.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

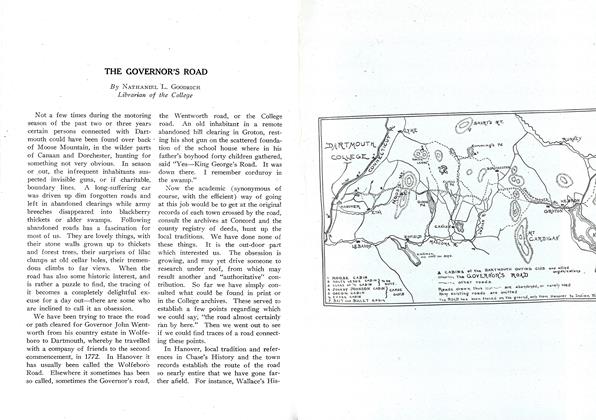

ArticleTHE GOVERNOR'S ROAD

April 1922 By NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH -

Article

ArticleRecent criticisms by President Meiklejohn of Amherst College directed toward

April 1922 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

April 1922 -

Article

ArticleRECOLLECTIONS OF RUFUS CHOATE

April 1922 By Miss M. A. CRUIKSHANK -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

April 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleNOTES

April 1922

Article

-

Article

ArticleTUCK SCHOOL LECTURES

December, 1909 -

Article

ArticleContributions by Classes in 1944 Alumni Fund Campaign

January 1945 -

Article

ArticleAdvising by Consent

October 1979 -

Article

ArticleCharles, the Team Could Use You Today

MARCH 2000 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Alumni Magazine and Operation Moonshooter

OCTOBER, 1908 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleCollege of a Thousand Elms

June 1937 By PROFESSOR CHARLES J. LYON