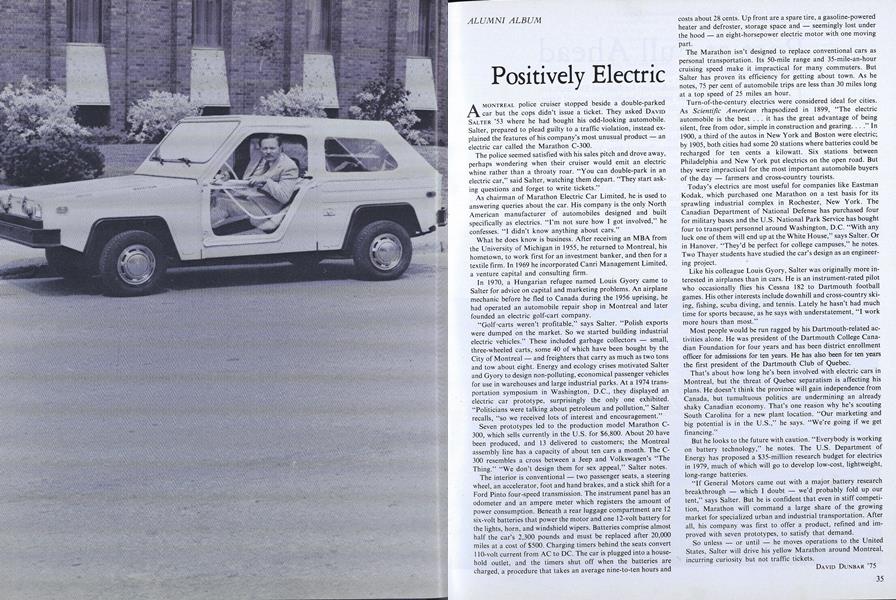

A MONTREAL police cruiser stopped beside a double-parked car but the cops didn't issue a ticket. They asked DAVID SALTER '53 where he had bought his odd-looking automobile. Salter, prepared to plead guilty to a traffic violation, instead explained the features of his company's most unusual product - an electric car called the Marathon C-300.

The police seemed satisfied with his sales pitch and drove away, perhaps wondering when their cruiser would emit an electric whine rather than a throaty roar. "You can double-park in an electric car," said Salter, watching them depart. "They start asking questions and forget to write tickets."

As chairman of Marathon Electric Car Limited, he is used to answering queries about the car. His company is the only North American manufacturer of automobiles designed and built specifically as electrics. "I'm not sure how I got involved," he confesses. "I didn't know anything about cars."

What he does know is business. After receiving an MBA from the University of Michigan in 1955, he returned to Montreal, his hometown, to work first for an investment banker, and then for a textile firm. In 1969 he incorporated Canri Management Limited, a venture capital and consulting firm.

In 1970, a Hungarian refugee named Louis Gyory came to Salter for advice on capital and marketing problems. An airplane mechanic before he fled to Canada during the 1956 uprising, he had operated an automobile repair shop in Montreal and later founded an electric golf-cart company.

"Golf -carts weren't profitable," says Salter. "Polish exports were dumped on the market. So we started building industrial electric vehicles." These included garbage collectors - small, three-wheeled carts, some 40 of which have been bought by the City of Montreal - and freighters that carry as much as two tons and tow about eight. Energy and ecology crises motivated Salter and Gyory to design non-polluting, economical passenger vehicles for use in warehouses and large industrial parks. At a 1974 transportation symposium in Washington, D.C., they displayed an electric car prototype, surprisingly the only one exhibited. "Politicians were talking about petroleum and pollution, Salter recalls, "so we received lots of interest and encouragement.

Seven prototypes led to the production model Marathon C- 300, which sells currently in the U.S. for $6,800. About 20 have been produced, and 13 delivered to customers; the Montreal assembly line has a capacity of about ten cars a month. The C- 300 resembles a cross between a Jeep and Volkswagen's The Thing." "We don't design them for sex appeal," Salter notes.

The interior is conventional - two passenger seats, a steering wheel, an accelerator, foot and hand brakes, and a stick shift for a Ford Pinto four-speed transmission. The instrument panel has an odometer and an ampere meter which registers the amount of power consumption. Beneath a rear luggage compartment are 12 six-volt batteries that power the motor and one 12-volt battery for the lights, horn, and windshield wipers. Batteries comprise almost half the car's 2,300 pounds and must be replaced after 20,000 miles at a cost of $500. Charging timers behind the seats convert 110-volt current from AC to DC. The car is plugged into a household outlet, and the timers shut off when the batteries are charged, a procedure that takes an average nine-to-ten hours and costs about 28 cents. Up front are a spare tire, a gasoline-powered heater and defroster, storage space and - seemingly lost under the hood - an eight-horsepower electric motor with one moving part.

The Marathon isn't designed to replace conventional cars as personal transportation. Its 50-mile range and 35-mile-an-hour cruising speed make it impractical for many commuters. But Salter has proven its efficiency for getting about town. As he notes, 75 per cent of automobile trips are less than 30 miles long at a top speed of 25 miles an hour.

Turn-of-the-century electrics were considered ideal for cities. As Scientific American rhapsodized in 1899, "The electric automobile is the best ... it has the great advantage of being silent, free from odor, simple in construction and gearing... In 1900, a third of the autos in New York and Boston were electric; by 1905, both cities had some 20 stations where batteries could be recharged for ten cents a kilowatt. Six stations between Philadelphia and New York put electrics on the open road. But they were impractical for the most important automobile buyers of the day - farmers and cross-country tourists.

Today's electrics are most useful for companies like Eastman Kodak, which purchased one Marathon on a test basis for its sprawling industrial complex in Rochester, New York. The Canadian Department of National Defense has purchased four for military bases and the U.S. National Park Service has bought four to transport personnel around Washington, D.C. "With any luck one of them will end up at the White House," says Salter. Or in Hanover. "They'd be perfect for college campuses," he notes. Two Thayer students have studied the car's design as an engineering project.

Like his colleague Louis Gyory, Salter was originally more interested in airplanes than in cars. He is an instrument-rated pilot who occasionally flies his Cessna 182 to Dartmouth football games. His other interests include downhill and cross-country skiing, fishing, scuba diving, and tennis. Lately he hasn't had much time for sports because, as he says with understatement, "I work more hours than most."

Most people would be run ragged by his Dartmouth-related activities alone. He was president of the Dartmouth College Canadian Foundation for four years and has been district enrollment officer for admissions for ten years. He has also been for ten years the first president of the Dartmouth Club of Quebec.

That's about how long he's been involved with electric cars in Montreal, but the threat of Quebec separatism is affecting his plans. He doesn't think the province will gain independence from Canada, but tumultuous politics are undermining an already shaky Canadian economy. That's one reason why he's scouting South Carolina for a new plant location. "Our marketing and big potential is in the U.S.," he says. "We're going if we get financing."

But he looks to the future with caution. "Everybody is working on battery technology," he notes. The U.S. Department of Energy has proposed a $35-million research budget for electrics in 1979, much of which will go to develop low-cost, lightweight, long-range batteries.

"If General Motors came out with a major battery research breakthrough - which I doubt - we'd probably fold up our tent," says Salter. But he is confident that even in stiff competition, Marathon will command a large share of the growing market for specialized urban and industrial transportation. After all, his company was first to offer a product, refined and improved with seven prototypes, to satisfy that demand.

So unless - or until - he moves operations to the United States, Salter will drive his yellow Marathon around Montreal, incurring curiosity but not traffic tickets.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Company of Stretchers

September 1978 By Cay Wieboldt -

Feature

FeaturePoet at Full Ahead

September 1978 By Charles G. Bolte -

Feature

FeatureTHE RIVER and THE DAMS

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleDickey-Lincoln: Who wants it? Who needs it?

September 1978 By Greg Hines -

Article

Article'A Spirit of Fire and Air'

September 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION