Friend Squoddy, with the caution of an elderly person on an icy slope, was feeling his way through a line or two of Latin poetry. It was sight reading for old Squoddy because Professor Parker, for once deceiving the trustful, had shuffled the whole pack and Squoddy had recited the day before. Res angustae domi,—things—narrow things-of the house", he extemporised. The good professor, with a little haste but with his unfailing courtesy and without even a groan of anguish, interposed, "Well, well, it may be so; it may be so; but don't you think 'straightened circumstances at home' would give us a better idea of the poet's meaning?" Squoddy paused to reflect and to take a swift backward kick at the neighbor who had driven his toe sharply into the hollow of Squoddy's knee, and then with obvious admiration accepted the professor's rendering. The professor beamed with joy and covered Squoddy's presumable embarrassment by the apt and sympathetic comment that many a young man pursuing his way through, college knew the meaning of straightened circumstances at home and of the sacrifices made for his education.

From an horizon of straightened circumstances a day of small things naturally arises and continues. So it was at Dartmouth during the major part of the years since my first acquaintance. The condition was even as bad as in the story told me by an old grad of less than fifty and more than forty years ago :-—"When I came to college we lived in Harmony, but my father soon moved to Boston. For two years, however, I gave in my name for the catalog as a resident of Harmony; but, the third year the Prof said when he was getting the enrollment, 'As long as your father really lives in Boston won't you put in your name as from there ? We haven't got any one from Boston, and we want to show at least one.' " This was worse than the destitution of the drunkard s home. The children called for bread and spinach and calories and vitamines in vain, and as a last hope they cried out for pie. "AND THERE WAS NO PIE IN THE HOUSE!" There was no one from Boston in the College! I believe this, so I have not looked it up in the catalog.

But straightened circumstances and the day of small things may be rich in satisfaction and good cheer. Everything depends upon the proportion in which the tranquility and happiness of life are derived from things or persons or ideas.

During the later period of penury, which extended well into the 90's, the salary of a "full professor" had risen to $2,000, and this with relation to the conditions of work and to the college expenses in general was liberal. Rightly the proportion followed the custom of the body and gave preference to the brains. These salaries were the consummation of three months' hope and trust; but there was no assured pay-day even then. As a personal favor however, the genial treasurer would advance a few dollars to loosen the financial stringency and set new money in circulation. Whether or not this $2,000 was more than whatever they do get today, in relation to what it would buy, is an open question. Measured by certain expenses which do not make the whole of life, it was enough. We were warmed and clothed and fed. Measured by the needs of scholars who should live in the world and be a part of it, it fell short.

There was food enough for hospitality, and at those delightful supper parties served at separate tables, the quality and abundance was up to the best New England standard; for there were notable housewives in those days, who provided an excess of exceedingly good victuals which it was the duty of the loquacious sisterhood in the kitchen to keep from spoiling. Help was easily obtained, and rarely was a family without one or two maids who gladly allowed themselves to be lent on these festal occasions. These parties, which were numerous in the autumn when one or two new members had been added to the faculty, had for entertainment after the dishes had been cleared away conversation, music, charades which we thought very clever, and little games in which the wits were caused to function pleasantly, like writing impromptu verses or presenting brief literary efforts, selected or original. And even if I am the only one left to say so, I will declare that hospitality, music, and gambols of the mind are more satisfactory sports for intelligent beings than moving pictures, cards or dancing. This statement is only comparative, and contains no positive denunciation of the latter class.

Private hospitality had abundant opportunity in those days, and met it well. As you see at Commencement the long retinue of the 10-years class—the wives keeping up with the procession regardless of heat or fatigue, proudly flourishing the showy parasols provided by the class tax, and the little Billikins here and there inspecting daddy's college whither they are coming by and by—you wish to know where these welcome ornaments of the occasion were stowed away in the days of yore when there were neither dormitories to give them shelter nor College Hall to give them food. Well, they were not expected, and they met the expectation. But there were guests, and Commencement was a more intimate family affair than at present. When the scant accommodations of the Dartmouth Hotel had been exhausted, the homes of the village were opened, naturally for the more mature alumni with their wives, if these chose to come. It was perhaps as much a reunion of friends as of classes. The young fellows could look out for themselves; and this they did without any vow to silence. Then to fill the meeting-house and the village a host appeared in the morning and vanished at night. The Commencement ceremony was a five-hours' orgy of oratory, during which the auditory tide ebbed and flowed and was anhungered. Some yielded to necessity and exchanged coin for sandwiches, peanuts or pie. But the ladies of the faculty and other friendly persons spread lunches, abundant, delicious and free, and sent out to collect the unfed. The lunch must be eaten. One of my older colleagues arrested me, only a resident, upon the street, with an urgent invitation to go around and eat his wife's lunch and thus lessen her worry lest too few should

come in and partake. But the multitude was not backward, and the lunches were seldom neglected. My wife once asked a senior — he will not see this - to bring in his friends, if any were here. He came, and he brought thirteen with him who ate and went away satisfied.

Taxes were a strangely unimportant item. The first tax I paid on the house I now occupy was $18.10; the last was over $200. But those conveniences, or as we now think necessities, for which taxes pay were also unimportant. The standard of living was a standard of isolation not commensurable with the life of the remote world of fashion. One can see now that the professors who gave the College its strength suffered from their inability to meet with men of similar interests. Good, learned, selfdenying teachers as they were, their influence would have been more virile if they could have conveyed to their students the impression that they had ever been out of Hanover. The salaries did not encourage families, and one at least who brought up a group of children can testify that notwithstanding undesirable economy, he was unable for many years to meet the necessary expenses except by outside earnings.

If instruction represented the height of wise expenditure, administration represented the depth of distressing insufficiency. Today you see a fine building, well-equipped, and wholly used for administrative purposes. What had the College at the time and during the period to which I refer? Nothing; absolutely nothing. With enough perseverance the treasurer might be found in his law office over the old bank building; and the president was often in his study at the house. Except for such domestic arrangements as he might make no member of the faculty had an office or anything corresponding thereto. He might have a study, and that, with a longtailed coat and a book, was enough. At present there is a considerable library building, inadequate, but storing or distributing 150,000 books, and capably administered. The college library of those days, well-hidden in the second story of Reed Hall, contained 17,000 books, and no one knew when the lone librarian would drop around and unlock it; I suppose there were regular hours, but who would expect us to know them! The Society libraries offered freer access to about an equal number of books. We drew for vacation choice by lot, and for the long vacation we could take away fourteen books, — seven from 1 to the highest number, and seven more from the highest number back-to 1.

At present the College gives steady employment to about 175 who do not have class-room duties; fifty years ago it had one full-time employe, the worthy but overloaded Professor of Dust and Ashes. Student help, which ranged from extreme fidelity to utter shiftlessness — only it was impossible to tell beforehand which it was going to be — was employed on a part time scale; and carpenters, painters, and the like, when needed were hired for the job. Considering the farflung precincts of the material college, the heating, lighting, feeding, the stupendous current details which enter into the daily book-keeping, the correspondence, the publications, the records which become history or statistics, only a rash person would declare, without expert examination, that too many are engaged in the business as distinguished from the instruction of the College. If, as is reported, it costs $8,000 a year to maintain the daily roll of attendance, one can at least imagine an institution in which this expense, made necessary because of delinquents, could be applied to something more productive, and the burden of nonattendance carried by the records of scholarship.

But what was the condition in a college set for about one-fifth of the present number ? The President wrote his own letters, aided now and then by some member of his family or by a student who wrote a fair hand and could be trusted. One student manipulated and pedaled the little organ. There was no superintendent of buildings, but upon some member of the faculty was wished the office of "Inspector"; $1.00 was added to his salary and he was bid go to it, — let the rooms, choose or help choose the wall papers, appoint the student janitors to sweep and tend the fires, invite the artisans to paint or paper or saw wood, meet the emergencies and take the blame. Another unhappy scholar was picked out and compelled to be "Clerk of the Faculty" upon the same terms; and upon him fell the duties of keeping the faculty records, the absences and the individual marks, and of making out the standing of the students three times a year. These term marks he naturally gave out in the simplest manner by handing a. written list to some convenient professor who distributed them in the class-room. In my catalog of 1868-1869 I find in penciled entries the marks of the freshman class of the time, ranging from 1.11 to 2.59 on the weird scale of 1. for perfect and 5. for zero. I note also that of 80 freshmen of that year only 16 were in college rooms.

There was no sabbatical year or half year. Nor had the generous subsidy to aid professors to become acquainted with their learned and jovial fellows at the annual meetings of the societies for the concentration of knowledge been thought of. Delegates to various organizations, less numerous than now, paid their own expenses or stayed at home; and a good many pairs of children's shoes could be bought for the money which one of these trips cost. Notice how essential it is for contact with modernity that artists and speakers of many kinds and grades should bring their talents to Hanover; these advantages were not for the small college and those who loved it.

Just what became of the professors who resigned before they died is not apparent. There were not many. In Lord's History we read that Dr. Sanborn, resigning in 1881 with insufficient savings after forty-three years' service, was assisted by an annual $500 contributed by friends. A president of the College who retired in 1892 was given a pension of $1750 which was afterwards cut to $1200. And this, I think, is the only case of a pension by Dartmouth College until Mr. Carnegie came to the rescue in 1906.

For audience rooms there was the meeting-house for preferred, the old chapel for common, and the gymnasium for special assemblies. Robinson Hall was not even a dream, and such few student organizations as there were floated around without a home, except the Theological Society which had a room with idols and things in it. College Hall has wrought a marvelous change in the humanity of the College. Before its construction the College was in the condition of a home without kitchen or diningroom — unable to nourish its own or to offer hospitality to others. Its operation may from time to time justify criticisms which should be heeded, but their weight is small when one considers what the Commons has brought about in raising the standard of alimentation throughout the village, in promoting genial discussion of serious topics, and in enabling the College to be a gracious host to organizations from within and without.

In a former article I have written of the primitive conditions of heating, lighting, bathing. If these had been the conditions of the civilized world at the time they would not have been so noteworthy; but they were not. While a little hand tub was available to squirt water on a fire until the horse-trough was empty or the soft-handed fire fighters were themselves pumped out, in the cities huge steamers were rushed with spectacular action to drown the fires with water. Nor can ignorance of water transmitted in aqueducts and applied in hot and cold baths be ascribed to a place of ancient learning. Although at this time plumbing had not become the royal art of the present, all the fixtures of what is often called a modern bath room had been m use for many years in modern communities. One of our professors gained great local renown at a fire of long ago. The fire company, discouraged before the battle by the heart-breaking work necessary to get the quickly-failing pipe-stem stream upon the fire, had little of the present efficiency, and their feeble and poorly directed efforts finally forced a student to explode with a series of those words which at that time were purged of evil in print by 2-em dashes in their middle. Professor Wiseman heard it all and placing his hand on the young man's shoulder said gravely, "Thank you, sir."

The Dartmouth was a solemn brown pamphlet published monthly, and each editor, having sole responsibility for his number, would beg his friends for literary contributions. The Aegis, a little paper-covered thing of about forty pages, was published twice a year. The number issued in the summer term of 1870, of which Charles F. Richardson was one of the two editors, contains lists of the members of the five fraternities which continue under the same name, of the Social Friends and of the United Fraternity, of the two freshman societies, and of the ten members of the Handel Society, ft lists a "quintette" which was very good — it was rumored, by the way, that this quintette glee club had swallowtailed coats which they wore on their infrequent trips —, a couple of minor musical organizations, seven baseball nines, class officers, a telegraph company, three burlesque groups, and the membership of the Theological and Missionary Association, in which are found the names of Francis Brown, Lemuel S. Hastings, Bishops ' Leonard and Talbot, Marvin D. Bisbee, Francis E. Clark, and many others since well known in Hanover. (I do not know anything that marks more the chasm between that world and this than the custom on obscure student authority — obscure even now to me — of dividing all'the members of the faculty among the four student prayer meetings on the Day of Prayer for Colleges.) The editorials of this Aegis are highly interesting. There is even then the call for a bath-room and for elective studies. A Commencement earlier than the next to the last Thursday in July is prayed for. There is an account of the laying of the corner stone of Culver Hall with the statement that the imported band's idea of an appropriate tune for the occasion was, "Put me in my little bed." There is the declaration that "the buildis really to be handsome and commodious," and the conclusion, "We had never expected to see with these mortal eyes a new building at Dartmouth, and now we hope that this one will be followed by a new dormitory, a chapel, and all the other buildings which have already been commenced on paper."

Our most proudly exhibited recitation room was the North Latin room. If you were to enter Dartmouth Hall by the south door, proceed halfway through the building, then turn sharply to the left and go through the partition wall into the lecture room you would be within the shade, the astral body as it were, of the North Latin room. It had recent settees in place of the ancient benches; and I seem to remember large photographs upon its walls—the Roman Forum, the Colisseum, the Arch of Titus, perhaps. Why the South Greek room, similarly situated at the other end of the building, was held inferior I do not know; but it was, perhaps because there was more flunking in it. On the 2d floor of Dartmouth Hall was the Senior room, of a peculiar sanctity which was fostered if not wholly inspired by Dr. Noyes. A. recitation room was a recitation room, and if there were a chair and a table on a platform for the professor and seats for the students there would be no occasion for any one to boast about Mark Hopkins and the log.

The time to which I refer—1868 just now — belongs to a period when if an institution of learning possessed a laboratory of any kind for student work it had the right to point with pride. So far as I have been able to learn Dartmouth had none. . There are a few rays of circumstantial evidence that somewhere and somehow the students in the Chandler School had a little "practical" chemistry, but I have never found out where or how. There was one course fairly in the same class with laboratory work—field work in surveying required of the whole sophomore class. Imagine being privileged to seek knowledge and skill out of doors in the early fall, while yet the sun was warm, the grass green, the foliage unthinned, and the fuliginous river fog foretold a gladsome day! The class was divided into squads of eight, with director and register committee on observation and calculation appointed by the professor on the basis of marks in mathematics, and a committee on apples appointed by the squad on the basis of specialized acquisitiveness. And neither committee was to be disturbed in its duties by other members of the squad. 1 here was no occasion to worry because the College had no ill-smelling laboratories. A little later by arrangement with the Agricultural College there was opportunity for seniors to have some laboratory work in Chemistry in the newly built Culver Hall.

The village had no welcome, for newcomers. I mean the village, and not its inhabitants. The writer was told by Treasurer F. Chase, with prophetic truth, that to get a house he would have to wait for some one to die. All the houses were occupied, and the land since available for building purposes was held in large tracts and was not then for sale. Nearly, if not quite, half the residences of the village are on lands then held for farms or hay fields. President Bartlett, who came to the College in 1877, was no better off than other intruders into the closed village, and for several years went from one temporary shelter to another — the Dartmouth Hotel, Mrs. Thomas Crosby's, Professor Emerson's during his absence in Europe, — until at his prompting the Trustees, with the purchase of the Noyes house, established the custom of maintaining a home for the president of the College.

One of the very good customs of the days of small things was the Senior Party given by the president a few weeks before Commencement. Personal invitations were sent to the Seniors and such friends of theirs as might be in Hanover at the time, to the social element in the village, and to friends of the College in neighboring towns — Lebanon, West Lebanon and Hartford. It was always an interesting question which and how many of these bespoken ones would reply to the polite notes of invitation. The seniors appeared in reasonable numbers; the guests from the neighboring villages were at pains to be present; "mixers" were appointed to stimulate circulation, and the usual good time was had by all. The party was held in the president's house when he had one. During the time when he was houseless one of the best of the gatherings was held in the old "Philosophical Room" in Reed Hall, and members of the president's family took off their coats or rolled up their sleeves and ladled out ice-cream for the multitude. The Senior Party pertained to the old style of home-made hospitality, to the simple era when people found entertainment in meeting one another and joy in exercising their own wits. It brought to the College a very desirable group of neighbors, and recognized, if only tacitly, the common migration from the old Connecticut homes. Within a few weeks one of the oldest of the guests was recalling with great pleasure these occasions which used to bring him and his wife on social missions to Hanover. With the great growth of the College this form of intercommunity had to pass away. Extinct also, like the Old Pine and the Senior Party, is the pleasant custom of faculty reception evenings, which for a time more than half of the members of the classes appreciated by their presence. We have the omelet, but the eggs are broken.

In June, 1878, the Trustees appointed an Associate Professor of Chemistry at a salary of $l5OO. He was associated, because Dr. Oliver Payson Hubbard was Professor of Chemistry, though for many years his relation to the College had been as lecturer in the Medical School. This associate professor after using up a leave of absence, arrived in March and began to look around for those material objects which go with a professor of chemistry. He found to his •surprise that the College was unable to offer him one square foot of separate and distinct territory, and that his outfit, when he found a place to put it, would consist of a little apparatus of small value the equity of the College in stock held by the Agricultural College, and what he could buy with an appropriation of $200. The work of the department was to be done in Culver Hall, a building of joint ownership, but in the custody of the N. H. College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts. It surely presented a situation for controversy and real trouble. There was one lecture room and one laboratory room and two men teaching chemistry to two distinct and immiscible groups of students. Hours, of course, had to be arranged for the use of the lecture room, and a gentleman's agreement was negotiated to leave no illustrative material around in one another's way. An attempt was made to get along with opposite ends of the laboratory, but, as that proved impracticable from the easy mixing of movables, a slight partition running half way to the ceiling was set up, and the associate professor found himself in possession of 24 tables and a closet, with standing-room only. This condition of two families in the same house continued until the removal of the N. H. College from Hanover in 1893. That it existed without friction or accumulated ill feeling is not wholly due to the pacific nature of the parties thus tied together. It was like the case of the female whose relative by marriage when asked if she was reconciled to departing from this life, replied: "She jolly well had to be."

Slowly, very slowly, almost inch by inch, the chemistry department pervaded, infiltrated Culver Hall. Its progress was aided by the imperfect ventilation of the building; and aliens, chemically speaking, gradually manifested an active preference for the nameless smells of a close room somewhere else to the clean and namable though perhaps too distinct odors of scientific preparation there diffused. The building became unpopular. And thus and otherwise, from nothing, in the course of many years Chemistry got possession of the whole building; and the migration into the beautiful new Steele Laboratory was but the natural translation.

Culver was not heated by steam or by anything else. The impediments to freezing were stoves needing constant feeding which they did not get, and a viciously inefficient wood furnace under the laboratory. Many a time the professor, after the manner of the district school, was compelled to call for volunteers from his class to accompany him to the cellar for fuel, generally getting a hearty response from the whole class. It froze in the laboratory, only occasionally hard enough to split the pipes; but, owing to the necessity of meeting an early schedule and of avoiding conflicts, much preparation had to be made before the classes came from chapel, with fingers so numb that the sight of blood from a cut or scratch was the first intimation of injury. For a time there was gas, Hanover gas, that peculiar semi-vaporous substance made on the spot and distributed to consumers at $10 a thousand until ruin stared maker and user in the face. After that for a long time the only heat for chemical purposes was obtained from little alcohol lamps. The professor was absolutely without assistance even from a helping janitor. But he had only to prepare and take down experiments and illustration for the class-room, wash the dishes, make up the reagents, give out all materials needed by students in the laboratory, keep up supplies and accounts and records, tend the fires in emergencies, dust the tables, circulate among the workers and catch them by intuition just before they made a fatal blunder, examine the note-books, have recitations and lectures, lay out courses which could be carried on under the limited conditions, and all the time strive to build up a regular department of .chemistry. Oh, it was a busy life! At times, as a nice little family accumulated, there would be for a treat a picnic down to Culver to unpack invoices of chemicals or apparatus. Relief came gradually, by volunteer student help, by students paid by the hour, by graduate students, by a full time helper, a practical janitor, and so on to the present accomplished staff.

I should like to enlarge upon the two little stoves at the south end of the Meeting-house with the rods of dripping pipe under the galleries delivering what was left of the smoke into the twin chimneys on the north, upon the choir loft over the door, upon the Thursday evenings rigidly reserved for the mid-week meetings to the exclusion of all other entertainments, sacred or profane. I should like to tell of the excitement among the required attendants .at the Sunday services when Dr. Leeds solemnly said "I pass," or rhetorically raised his voice to cry "Wake, Christian brother!"; or when the visiting clergyman in telling of his service at the State's prison said, "They were all there; they had to be." The social and inexpensive decoration of the church for Commencement, and the rich bouquets presented to the speakers are items of interest. Much might be said of the forlorn lot of the sick student — for measles, mumps, scarlet fever, whooping cough and something just as good as the grip flourished then — shut up in his dirty room and in his unchanged bed and tended only by his kindly but erratic fellows; and of the winter hibernation with occasional giddy awakening when Anna Dickinson, General Kilpatrick, Camilla Urso, or the Jubilee Singers broke in; and of the inevitable February row of some kind in the College. But there must be consideration of the limitations of space, time and patience.

Times change and we have changed with them. Those were hard and happy days, and their recollection calls for no pity.

"Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot

Professor of Dust and Ashes

The Philosophical Room, Reed Hall

The Whole Chemical Laboratory, Spring of '87 A Section of the Class of '88

Required Laboratory Work Sophomore Year Autumn of 1869

EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry, Emeritus

EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72

Article

-

Article

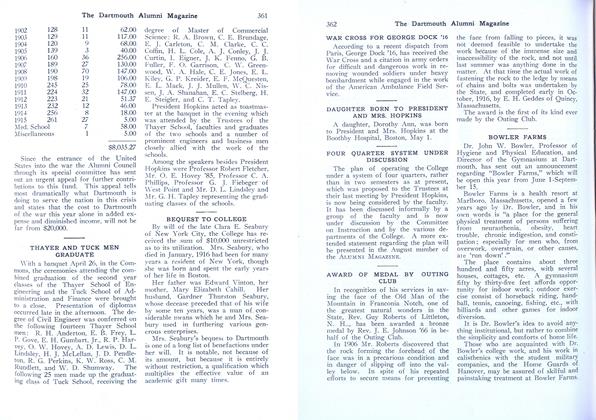

ArticleWAR CROSS FOR GEORGE DOCK '16

June 1917 -

Article

Article1953 Alumni Fund Opens Campaign for $600,000

April 1953 -

Article

Article'58 Alumni Fund : $455,301

OCTOBER 1958 -

Article

ArticleWhere We Are

APRIL 1997 -

Article

ArticleRAY NASH AND GRAPHIC ARTS

February 1941 By Robert R. Rodgers '42. -

Article

Article"HEAR DEM BELLS"

December 1935 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36