Sheridan to Robertson. A Study of the Ninetenth-Century London Stage. By Ernest Bradlee Watson. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. 1926.

Here is one of the most important books ever written by a member of the Dartmouth faculty and one of the most important books on the theatre published thus far in the Twentieth Century. Engaging himself with a period in the history of the modern English stage—the first sixty years of the Nineteenth Centurythat we have been content to dismiss with contemptuous generalities, Professor Watson has brought order and relationship out of the huddle of materials that awaited the investigator and has proved that this period, superficially so sterile, was in reality a period of undiminished creative energy, a period in which the "lifestream" of the theatre, that phenomenon of arterial activity which all students of the drama must take into account and nevertheless fail repeatedly to take into sufficient account, carried on unchecked. That this creative activity manifested itself in other directions than in the enrichment of English dramatic literature makes no difference. English dramatic literature was enriched in the long run. For a time the lifestream "flowed by way of the theatres' and not by way of the dramatist's closet. ... It was the peculiar business of the age to adjust stage conditions for the reception of a new type of written drama. When those conditions were sufficiently adjusted, the new drama was forthcoming."

The "new drama" toward which the English stage was developing was, of course, the drama of realism. Into this movement toward realism (and when one employs the facile term he should make the mental reservation "comparative realism") entered gradually every department of stage activity "but first and most notably, the arts of the scene-painter, the costumer, the manager, and the actor." At length arose the culminating figure, Robertson, (aided by the Bancrofts) who "grasped the meaning of contemporary stage developments" and made the art of the playwright fulfil the tendencies that for quite half a century had been coming to birth on the London stage.

The book is thus a satisfying demonstration of the thesis: "Things don't happen all at once." It throws a new light on the entire period. It puts Robertsonian comedy into its proper relationship without detracting in the slightest degree from the inherent value of that comedy. It proves once again that seldom in the art of the theatre (far more seldom, indeed, than in any other art) does the isolated or disconnected phenomenon come to pass. (This, if you like, by no means precludes the doctrine of the Heroic in literature).

The book offers, too, a more reasonable ex planation than has yet been offered for the prevalence of French drama on the English stage in the pre-Realistic days of the Nineteenth Century. The "absence of international copyright, the lack of adequate English plays, the parsimony of London managers have been variously put forward as explanations for the successful invasion from across the Channel. But they are only half the story. In reality, as Professor Watson points out, the "French novelties" gave the English audiences precisely what they were reaching out for in their satiety with ineffectual imitations of the Elizabethan stage. Being themselves a part of the general movement toward realism, the "French novelties far from stifling the native English drama stimulated it to develop a realism of its. own. They helped to create an appetite instead of operating to poison a food.

Professor Watson's perception of this capacity of a theatre-going public to reach out for some new vital creation which it is unable to imagine and create for itself is indicative of the discernment and wisdom which make his book essentially of the living theatre. Nowhere does the author lay his finger more directly on the pulse of the English stage than in his refusal to blame the taste of the theatre-going public for the dearth of native drama in tlw period with which he deals. "Had writers, even in those days, put before the public, under slightly more favorable stage conditions, a really vital and meritorious drama, there is little doubt that it would have been understood and appreciated. And further, in a slightly different connection: "What the British public has consistently shunned at all times are the abortive attempts to write for the stage on the part of poets, essayists, critics, preachers, and novelists, who, with little or no knowledge of the stage, and less of the technique of the written drama, have made the attempt to catch the public mind through its favorite art. . . . The two chief requisites of stage success have been wantingfirst, knowledge, intimate and complete, of the living stage; and second, a still more intimate and complete understanding of the hearts and minds of the audience to which the appeal is to be made."

The work that must go to make a book of this kind is two-fold in nature. The facts must be interpreted but, to be interpreted, the facts must first be gathered. No one can fully appreciate Professor Watson's accomplishment in his mere gathering of the facts who does not realize that Professor Watson was working in territory, overwhelming in extent, where no one had worked before him. No one can fully appreciate Professor Watson's achievement in that territory who does not know something of the obstacles that confront the worker in unsettled regions of the drama, obstacles ranging from the minor discouragements of dateless play-bills and unindexed bound volumes of theatrical comment, to the major discouragement encountered when one tries to cut through the network of puffery and back-scratching, of triviality and personal grievance that enmeshes so much of the theatrical journalism of the time.

The very nature of his approach makes it imperative that Professor Watson examine in detail the developments over half-a-hundred years in his various "arts of the scene-painter, the costumer, the manager, and the actor," and bring these into a relationship as exact and as clear as may be. In addition, the scope of the work includes biography, dramatic criticism, literary anecdote, social history, and something of what was happening to the drama in France. Under such circumstances selection becomes a labor of the most bone-shaking difficulty and the task of keeping a clear head above the mass of indiscriminate materials is one well-calculated to bring a pallor into the cheek and a mist before the eye.

How well Professor Watson has succeeded is made* evident by his painstaking treatment of his separate items: financial development in the theatre, scenic development, histrionic development (to mention only a few) and by the way in which these separate items are merged in the whole design.

Professor Watson has selected wisely and has kept his glance fixed unwaveringly on the larger conclusions to be derived from his study. The plan of the book makes inevitable an occa"Never-grow-old sional sense of repetition and over-lapping. The space at his disposal and the necessity of maintaining his proportions (the fact, perhaps, that he was writing one book instead of twenty) makes it impossible for Professor Watson to develop in detail some of the most interesting minor points that he raises. I found myself wanting to stop all along the way and discuss or hear more about these minor points.

It may well be that they will serve as points of departure for future studies. It may well be, and it very probably will be, that the whole book will serve to open up its period to students of the drama. For definitive as 'I believe the book to be, establishing the general truth about the time beyond reasonable challenge, and exhibiting new aspects of several of the most important figures of the time, it by no means says all that is to be said upon the subject—as if anyone ever could.

The book is careful, discriminating, and true. But what gives it its greatest distinction is the sense of the theatre as a living organism that it manages to convey. Behind the printed word is the play-house itself with all the influences that stream about it; the play-house that is so greatly and so eternally a human thing.

Here by some magic, partly instinct in the subject and partly instinct in the approach, is London, London of the Monopolies, Covent Garden', and Drury Lane. The Time-Spirit, a grizzled veteran of the Napoleonic wars. Through fog the banners of the Legitimate drag limply. Cabroilet and hackney. Burletta and melo-drame. Oranges and inky play-bills. The smell of paint and the strong smell of gaslamps. Vestris, forgotten dryad of the Olympic. Dickens, Bulwer-Lytton, and Jerrold thronging Macready's green-room at Covent Garden. The "Theatrical Observer" and Cumberland's "Minor Drama." The name Kean; the name Kernble. The audacious name Elliston. The "Quarterly Revjew" complaining that something has "reduced the part of the community which has the power to enjoy, and the inclination to support the drama, to comparative insignificance." Is it movies or radio?—stay, we are in 1831; it is the Circulating Libraries that the "Quarterly" means. The name Boucicault. Limping Dundreary. The name Bancroft. "Society." "Caste." And presently, "nous avons change tout cela."

And through it all, Behemoth and Leviathan, the British Audience. Tough-grained oak and lungs of clanging leather. Capable of meeting Doomsday itself with the single splintering epithet, "Un-English!" Sitting through Queen Katherine's dream "entranced as though divinity indeed were arranged before them" or dispatching Robertson's son to report failure to the dying dramatist: "Ah, Tommy, my boy, they wouldn't be so hard if they could see me now. I shan t trouble them again." Maw capricious and unfathomable. Yet somehow, in the long run, thrustworthy. And whether one likes it or not, prevailing in the end. The British Audience.

The Historical Outlook for October contains a review of the first five volumes of the Pageant of America series published by the Yale University Press. Of volume v of this series written by Professor Malcolm Keir we read:

The Epic of Industry" is an admirable companion to the Toilers of Land and Sea. It pictures the primitive era of muscular energy, the harnessing of the forces of nature, the colossal expansion of industry during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The pictures devoted to the steam-engine and its improvemets, to the development of power, and to the lumbering and mining industries, are especially noteworthy. The human side of our industrial civilization is also stressed by the inclusion of many pictures of great industrial pioneers, the man on the job, arid the conditions under which he works, and the history of organized labor." This volume contains approximately 650 illustrations.

The Granite Monthly for November contains an article on William Jewett Tucker by Professor Charles F. Richardson '71 late Professor of English. This tribute has never before been published.

"The Church of Christ in Holies: the First Two Pastorates 1743-1831," an address delive red on the occasion of the dedication of the new Meeting House, August 20, 1925 by Professor Charles Darwin Adams, has been published in pamphlet form.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1926 -

Article

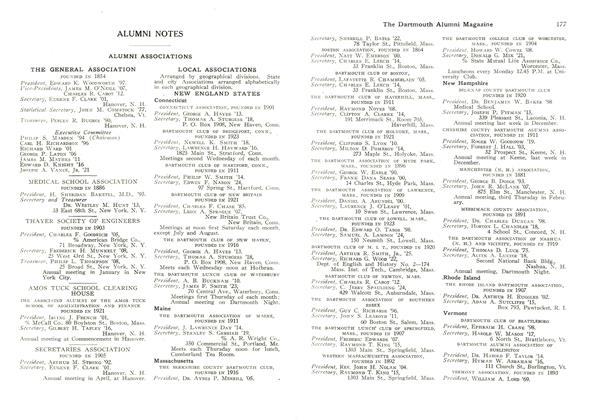

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1926 -

Article

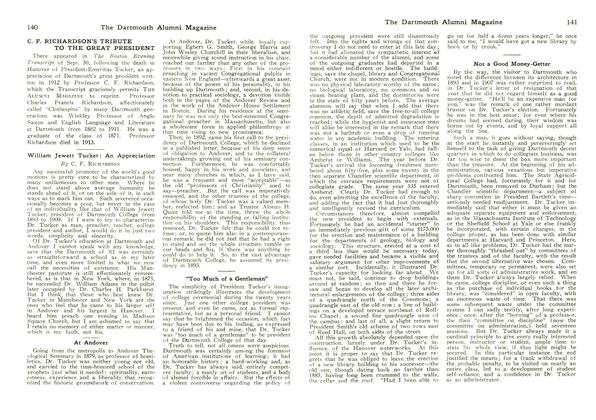

ArticleTHE COLLEGE CURRICULUM FIVE HUNDRED YEARS AGO THE MEDIEVAL COLLEGE

December 1926 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticlePHYSICAL FITNESS WORK AT DARTMOUTH 1925-26

December 1926 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Article

ArticleC. F. RICHARDSON'S TRIBUTE TO THE GREAT PRESIDENT

December 1926 -

Article

ArticleWHY THEY DON'T ATTEND MASS MEETINGS

December 1926 By Harry R. Wellman '07

Kenneth A. Robinson

-

Books

BooksTHE PEARL OF HER SEX,

November 1947 By Bill Cunning, KENNETH A. ROBINSON -

Article

ArticleMAY 3, 1923

June, 1923 By Frank L. Janeway, Francis J. Neef, William K. Wright, 3 more ... -

Books

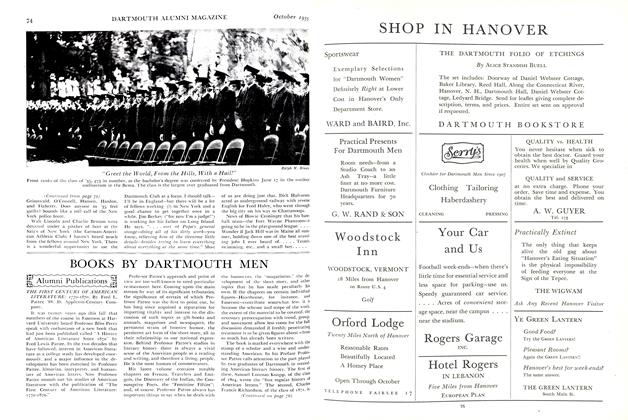

BooksTHE FIRST CENTURY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE

October 1935 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksFINGERBOARD

April 1950 By KENNETH A. ROBINSON -

Books

BooksTABARD

October 1951 By Kenneth A. Robinson -

Books

BooksCONTEMPORARY DRAMA, ELEVEN PLAYS, AMERICAN, ENGLISH, EUROPEAN.

June 1957 By KENNETH A. ROBINSON

Books

-

Books

BooksAmerica's Town Meeting of the Air.

April 1936 -

Books

BooksMATHEMATICS IN MEDICINE AND THE LIFE SCIENCES.

OCTOBER 1966 By JOHN PHILIP HENRY, M.D. -

Books

BooksTHE BRITISH IN NORTHERN NIGERIA.

JANUARY 1970 By LEO SPITZER -

Books

BooksUrban Romantics

April 1976 By NOEL PERRIN -

Books

BooksAMERICAN HEROINE: THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF JANE ADDAMS

October 1973 By ROBERT E. RIEGEL -

Books

BooksTHE ESSAY: A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY

July 1952 By Robert S. Kinsman '40