Address at the Opening of Dartmouth College, September 20, 1923

Education presupposes the mind of man. Moreover, it assumes the mind in action. In other words, education assumes the power of thought and the disposition to think. The question of greatest consequence here at this time is the extent to which this pre-supposition is justified within this group, — the extent to which such an assumption may prove to have been based on fact.

From time long ages past, when first uneasy stirring of the minds of primitive ancestors began to create vague longings for something better than then known and in the occasional individual to translate these from conscious intelligence into action, an ennobling motive has been added to the life of man, creating impulses and desires and accomplishments, commitment to which on the part of men in increasing numbers and with augmented intensity has raised the plane of action among mankind higher and higher above that of the beasts.

It is primarily with the defining, the strengthening, and the realizing of these aspirations that education has to deal. Granted the handicap under which the college labors, as do its individual members,- that so little is known about the mind and that what is known is so little applied, it yet remains true that the desirable purpose of the college is ineffective except as its men acquire from contact with it enhanced ability and will to use the mind, and increased discrimination how to distinguish truth from error.

It would be interesting and an enlightening piece of information were it possible to know how many men among this assembly had ever made conscious and deliberate attempt to have a thought. What do we mean when we say "I think" ? We hold opinions, some of us with great intensity, and most of us with great tenacity. But to what extent are these the product of thought ? Whence do they come? How are they derived? On what basis do we judge their worth? How sincere are we in our eagerness to possess those of genuine value? In the whole range of attainments possible to man there is no one so definitely divine as the ability to think. Yet taken in the large there is no capacity for which we have less conscious longing, to say nothing of the fact that there is none for which we less eagerly seek. We crave authority for opinions which by accident have become ours. We give little heed to how valid opinions best may be acquired.

Inevitably, to the extent that we attach seriousness to this enterprise to which we have committed ourselves—to the extent that "going to college" signifies seeking an education,—we must consider our goal before all else. Otherwise all our expenditure of time and energy is likely to be futile. We cannot even intelligently speculate on whether we are making progress or not unless we know the characteristics of that which we seek and the direction in which it lies. The greater our activity and the more hurried our step, the greater our wandering afield, if, without knowledge of where we are going, we fail to find the path which marks advance!

The goal of education is cultivation and development of our mental powers to the end that we may know truth and conform to it. Knowing truth requires something more than an occasional disposition to seek her out. No nodding ac quaintanceship or good-natured willingness to be friendly with her will give us real knowledge of truth. To know her requires unceasing effort to learn her lineaments in order that she shall be recognized when found, unremitting vigilance that she shall not pass by unseen, and the cultivation of high respect and deep affection for her and all her works. Moreover, education cannot be held to have been of large avail if it simply creates an attitude of passive acceptance of truth without inspiring likewise a devotion to the spirit of truth which shall breed a definiteness in the loyalty which we offer. They in whom the spirit of education has at all approximated its reasonable function must be doers of the word.

It is necessary to repeat and to re-emphasize these statements again and again if we are to re-define the college purpose and the college obligation. I said last year, what had doubtless been iterated frequently by many others, that with all of the imperative need for our knowing reality, there was no evidence that man had any instinctive desire to know truth, much less to do it. I repeat the assertion here because, if this be so, it has important bearing upon the college problem of what education is and how it is to be made effective.

Man acquires opinions as a result of the working of such forces as heredity, environment and self-interest and his instinctive desire is to substantiate the opinions so acquired. It is only by definite and painstaking effort that he winnows these and acquires determination to set about the mental threshing of any newly garnered store. Herein the college has its greatest opportunity, in helping the individual student to this acquired characteristic of a desire for truth and to knowledge of the principles under which it can most advantageously be sought. Obviously, if we follow common practice and read only those periodicals or treatises which argue for what we hold, or listen only to those who say what we maintain, or associate only with those who believe what we suppose, we cannot know the truth even if we happen accidentally to be affiliated with it.

In the large, education is quite a different thing from training, and the method of the educational institution calls for diversity in points of view and emphasis upon stimulating the student's thought, while the training school almost inevitably emphasizes instruction and demands conformity to the thought of others.

I believe that there may be question in regard to the contention of those who hold that an endowed institution has no right to be a training school; and I see no reason why there should not be labor colleges and colleges for the defense of capitalism, or schools of democracy and schools for the justification of benevolent despotisms, or schools with the purpose of striving for the establishment of the validity of one denominational contention or another in theological belief. But it is requisite that such an institution should not take exception to the classification of itself as a training school, and not primarily as an educational institution.

By the same token, but even more emphatically, it behooves the institution which boasts itself an educational institution to make good its claim, to avoid the spirit as well as the method of the training school, and to be in fact as well as in name truly educational.

Assuming then that in measurable degree by cooperation of the different bodies which constitute the college constituency we realize our aspiration to have this college genuinely an educational influence, and accepting as our sole ambition that we seek knowledge of the truth, it is meet that we should give some attention first to the conditions under which the quest is made and the circumstances which surround us as we undertake it! What are some aspects of the age in which we live and what is the spirit of our environment?

For our purposes it is- idle to discuss whether the spirit of the time is better or is worse than the spirit of former times. That it is different is the essential point. It would seem that we are not more free from pose and affectation than were the years of decades past but merely that the pose is inverted and the affectations are reversed. Whether or not we are more honest in the one posture than the other is not yet made evident. The now much-patronized and ridiculed Victorian age preceding our own time lacked genuineness in its professions, to be sure! Its mincing niceties, its attitudinizing with scenic effects of beauty and gentleness and sweetness, give just cause, in view of the actual conditions of the time, for much of the criticism which has been directed against it.

The question remains to be answered, however, whether in a world of intermingled goodness and badness we are essentially more honest now in tinting everything with the spirit of sordidness than we were then in tinging all with the semblance of light.

We formerly accentuated the presence among men of happiness and contentment and confidence; now we ruminate with melancholy gratification upon unhappiness and discontent and distrust. Self-depreciation and disavowal of existent elements of altruism and nobility within ourselves are habitual not only with ourselves individually but likewise with ourselves collectively. Does one with the instinct of a former time wish to believe that the sacrifices of the war were undertaken in a spirit not devoid of nobility and idealism, one more modern arises and asserts that self-protection was the only motive! Our most widely read popular weekly editorializes with a sneer for college officers who emphasize the need of idealism and spiritual leadership, and constantly by implication advances the "hard-boiled" attitude as desirable for useful citizenship. Great newspaper syndicates, together with foreign and domestic political leaders, accentuate self-interest as the only existent motive for individual, group, or state action.

There is possible gain in the absence of smugness and hypocrisy from the more recent attitude which is commendable, but so far as honesty and truthfulness go the latter condition is as bad as the former. We talk glibly about reality as though we had it now, but a stench to the nose, a blur to the eye, a discord to the ear are no more real than are perfume, symmetry and harmony. Let us not, then, start with assurance in any assumption that we are nearer truthfulness than we would have been at some previous age. The problem is admittedly changed and it is to that that attention must be given.

For our present discussion this' conjectural diagnosis of the temper of our period has only this importance, that what we purport to be tends in the course of time to influence what we shall be. The pose of the present is very likely but natural reaction from the. pose of the immediate past. With all its unpleasantness it still may claim the merit of an attempt at increased honesty through understatement and self-disparagement. Nevertheless, it should be considered whether there is not danger that the attitude which we perchance strike in a spirit of humility, may not, under other circumstances and in other times, come to be thought to represent a desirable standard and be taken in pride rather than, as now, in defiance.

It seems to me clear that even though we know the nature of organized society to be something different from a composite of the natures of individuals who compose it, nevertheless the natures of individuals vitally affect the nature of the group. If this be at all so, then the individual who does not will to be a slacker must hold his own actions and his own purposes as of vital significance to the social state, and must accept at least his proportional obligation for the influence upon society which he shall exert.

Herein we approach from one angle the problem which more than any other requires solution in these days of unrest and uncertainty: how to preserve to the needs of civilization the initiative and vigor and originality of individualism in conjunction with the responsibilities and necessities of associationalism. It is not a question of what we wish were so as regards personal detachment and independence of action, for not only is the world too much with us but it is cumulatively so. To abandon our instinct for individuality and to float upon the tide of mass opinion, mass emotion, and mass purpose, simply makes for the mass being more inert and more purposeless even than before. On the other hand, to arrogate to ourselves the privilege of asserting individual right, irrespective of its effect upon group welfare or group consciousness is futile, even when it is not harmful.

Somehow, if progress is to be made, new codes of action must be drawn, under which the difficult adjustment of individualism to group responsibility shall be shown to be practicable and in which the two motives shall be blended as best they may be, preserving to each the maximum possible of its peculiar attributes. No greater problem has ever confronted the mind of man. Certainly no greater challenge can be issued to the college in its capacity as representing the world of education.

Another aspect of our age which requires constant consideration is the professionalized point of view, with the resulting tendency to generalize in regard to life as a whole from the specialized activities of life with which we as individuals have most intimate association. Any one of us without undue effort can summon to mind examples of men in business, in politics, in the Church or in education, who from their justified assurance of mastery within their respective fields arrogate to themselves almost omniscience in prescribing desirable procedure for the conduct of the affairs of the world at large. Such men, when considering the responsibilities of others, fail almost invariably in exemplifying any of that humility with which they demand that others approach consideration of their own affairs.

It is not difficult to understand the wide prevalence of the professionalized attitude toward life. The scope of knowledge has become too great and the refinements of knowledge have become too exact for any man to be in possession of more than a fragment. At the same time, the constant effort necessary to maintain leadership, even if once acquired within a given field, largely denies the possibility of acquiring that acquaintanceship with the activities and needs of other groups which shall make for breadth of knowledge or for sympathetic understanding of the baffling problems which others face.

These tendencies are curtailing influences upon the advance of civilization when existent in the attributes almost invariably associated with the minutely subdivided and highly intensified activities of daily life. More important, and more vital to college problems, they become intolerable handicaps to progress when they become attributes of schools of thought having to do with social theory and the search for a valid philosophy of life. For instance, we have definite and disturbing illustration of this at the present time in the attempt of extremists who style themselves "Liberal" with a capital "L" to exploit in their own interest the field of liberal thought. This professionalized group, arrogating to itself all virtue and good intent, and denying these qualities to all others, patronizing those who will not whittle their conclusions to the exact dimensions of the prescribed code; manipulating intellectual processes and capitalizing dogmatic assertion as preferable to accepting the conclusions of logical thought, this group is doing more to breed suspicion of and hostility to true liberalism than is being done, or could be done, by all available forms of reaction if combined in militant array. Ill-nature, intellectual arrogance, and churlish intolerance are but sorry concomitants of any movement, but they are singularly out of place and tragically harmful in association with any movement which desires to be recognized as liberal. The mind tolerant of the opinions of others and open to conviction in the presence of new knowledge is more liberal than that of the bigot, regardless of the beliefs of either.

Herein, however, we have example of the difficulties to the individual of avoiding the limitations upon his own thinking, of classification, and of assignment to or appropriation by some group, to whose views he must accede and to whose dogma he must conform, if in the large his loyalty is not to be doubted to a cause which they have assumed to sponsor. The college man will meet no more puzzling and difficult example of the problem of adjustment of individualism to the requirements of associationalism. The great weakness of the professionalized point of view is that it fails to recognize that no fact is unrelated to other facts, and that final truth is found in the relationship, and there alone.

In such situations, and with the compulsion which the organization of life imposes upon us all, there is little opportunity and less inclination towards that reflective spirit through which alone well-balanced judgment can be formed, and upon which the educational method of earlier times so definitely insisted. It might well be considered as a practical matter of present day import whether the exigencies of modern life do not, more than those of any former age, demand the existence and the utilization of that procedure of former times by which men withdrew periodically from the stress of life and gave themselves to periods of purposeful meditation. It is possible that in such occasional detachment some minds would find themselves able to function with a power and with an accuracy which even the best achieve but seldom now. If the colleges could more nearly constitute themselves conservators of such an opportunity, rather than tend to become more and more mere hives of busy-ness, their sphere of usefulness to society at large would be likely to "become vastly increased.

I do not ignore the indispensability of the doer, the practical operator, the so-called "go-getter" in the life of this or any other time, but if action is to be well directed, is to be advantageous, and is to be conducive to progress, it must be subsequent to and in accordance with careful, intelligent and well-balanced thought which shall direct what is to be done, what is the needful operation, and what is to be got.

Gigantic forces are at work within the world, the effects of which cannot be dictated and the power of which cannot be withheld. The preservation of civilization is. dependent upon widespread acceptance of principles under which these forces shall be applied for the common good. The presentation and the securing of the acceptance of these principles is a primary task of education. The method must be by persuasion. Effort at compulsion, even if desirable otherwise, could not be made strong enough to be effective. We need to drop expectation of miracles and supermen and to reflect more and more on the fact that civilization has developed largely by the honesty of purpose and intelligence of effort of normal meu, subject to the influence of disciplined intellectual processes.

Blazing meteors flashing across the sky have in their respective times aroused terror, wonder, or admiration in the hearts of human beings, but their aggregate influence upon the emotions of man have been as nothing compared with the periodical light of the moon or the steady glow of myriads of stars. Convulsions have from time to time wrought gigantic destruction and violently modified portions of the earth, but through the ages the face of nature has been more changed by the continuing warmth and light of the sun than by all of these.

The burning, searing agitation of fiery reformers has from time to time influenced the life of man. Forces of destruction and the violence of revolution have on occasion wrought changes seemingly desirable for peoples of the world. But these are unnatural, wasteful, and tragical agencies for the accomplishment of what might be secured in other ways. The sum total of all amendment of life by these methods is insignificant as compared with the evolution which has come by constant effort of individual men to make life better. Let it not be forgotten that among these, the quiet influence of those men of scholarly instinct and scholarly attainments has been exceeded by none! The thought of the world has been moulded by its scholars.

We take up the work of our college course and stand upon the threshold of life at a time when the forces of suspicion, hatred, and destruction impend on a scale and with a violence unprecedented in the long life of mankind. At the same time, from many quarters, harshness of temper and selfishness of ambition are held up to us as attributes essential and desirable. Is it not the mission of the college to ask if advantages bought at such a price are worth while? More, is it not the mission of the college to afford intellectual and spiritual basis for the answer to this question?

Truth cannot be found by men unwilling to weigh the merits of any opinion but their own. Reality cannot be known by men who will accept no data except those conducive to their ends. Intellectual power cannot emanate from minds unused to thought. Yet mental discrimination, mental honesty, and mental power, are all indispensable to him who would be largely useful in such a time as this. May these qualities be ours.

That flickering spark of aspiration among the unkindled fires in the mind of early man, lighting advance towards better things, has from time immemorial increased in strength and glowed with increasing radiance, ennobling human action and illuminating the goal of human endeavor. It is with the perpetuation of this light that education has to do. The response that each man makes to the summons to guard this flame will be the final criterion of what is to be the worth of his life to mankind today and to the society of years to come. Upon you and your response the college waits for justification of itself !

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth College has entered upon

November 1923 -

Article

ArticleAFTER TEN YEARS

November 1923 By FRANK LATIMER JANEWAY -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1923 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

November 1923 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1923 By Ralph Sanborn -

Article

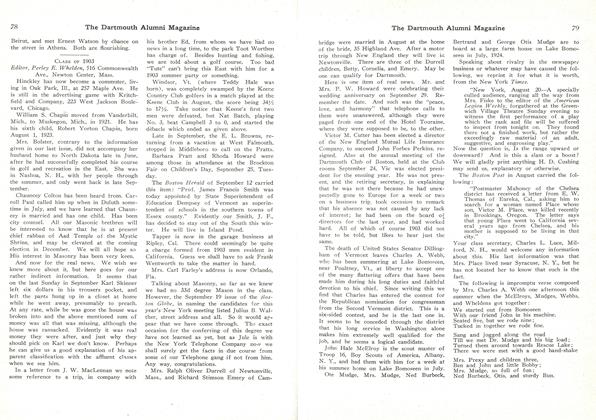

ArticleENROLLMENT FIGURES AND STATISTICS OF CLASS OF 1927

November 1923

ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE IN KHAKI—WHAT THE S. A. T. C. IS AND HOW IT WORKS

November 1918 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE: RETROSPECT AND OUTLOOK

July 1919 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE UNPROVABILITY OF MAN

August 1921 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE'S RELATIONSHIP TO THE COLLEGE

November 1921 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleAN ARISTOCRACY OF BRAINS

November, 1922 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

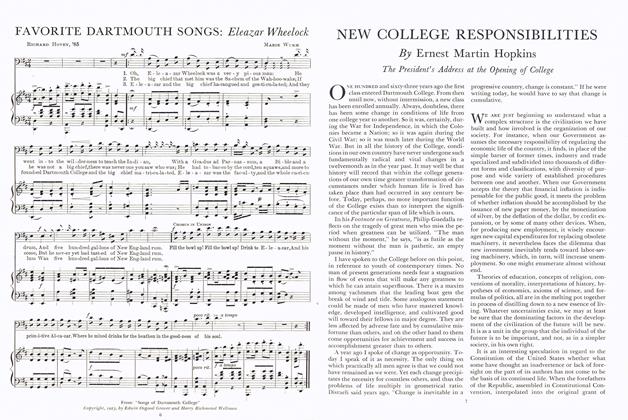

ArticleNEW COLLEGE RESPONSIBILITIES

October 1933 By Ernest Martin Hopkins

Article

-

Article

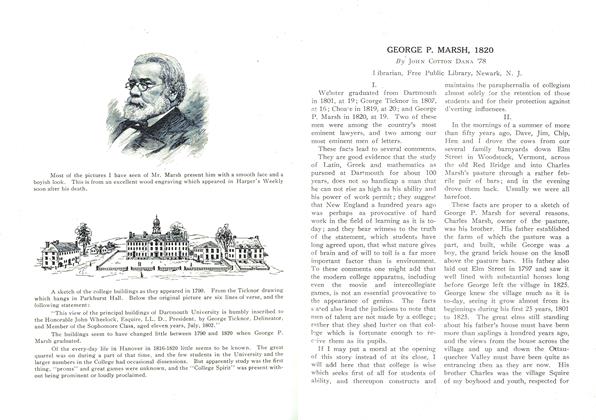

ArticleMost of the pictures I have seen of Mr. Marsh present him with a smooth face and a boyish look.

July 1920 -

Article

Article1901-05 Boston Dinner

June 1947 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

July 1953 -

Article

ArticleForm and Function

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Article

ArticleMaster of Arts

August, 1926 By HARLAN COLBY PEARSON '93 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1933 By Rees H. Bowen