DURING the past month a new undergraduate magazine, Greensleeves, was formed to replace the DartmouthQuarterly. Its provisional manager, Jon E. Mandaville '59, stated the reason for its formation: "We hope to attract many of the really good writers on campus by increased circulation and a revised format."

The first issue of the new magazine will come out during Green Key weekend, filling approximately 32 pages, and will contain several new features, according to Mandaville: many more pictures than the Quarterly had, better material, and a foreign language page. As the biggest innovation, this page will print poems, essays, and stories, and Mandaville expressed the hope that it will induce a few faculty members to write for the magazine.

Greensleeves is not yet a going concern at this writing, and many undergraduates are wondering if it will ever become one of the permanent campus publications. Often the fate of a collegiate business venture is sealed before it is properly begun. But we should like to point out that Greensleeves was not just "thought up" to be a vehicle through which the sophomoric pseudo-intellectuals of the campus might express themselves. It was conceived, rather, in terms of the needs the Quarterly had ceased to fill, yet with a significant difference.

The freshman and sophomore classes this past year have shown, through their academic course work, that they have exceptional writing talents in certain individuals. But in the tradition already imparted to these students, the Quarterly was something laughable. Greensleeves hopes to tap these men, and not having a "past" makes it essentially different from the Quarterly, rids it of the perennial stigma a collegiate literary magazine suffers in non-intellectual dormitory circles, and perhaps will make it successful.

Its success also depends, however, on another factor, and it should be weighed with care: the quality of writing the magazine exhibits in its first issues will determine the kind of copy which will subsequently be submitted to it. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that the editor for the coming year, Harry Kreamer '60, be extremely selective, for only by being very "choosy" at first will he be able to entice the new student writers into making regular contributions.

Greensleeves is the second student magazine to be started within the year - the other was Vox. Before this past year there was a twenty-year period devoid of new publishing ventures on the campus, although the Quarterly and Jacko changed their names frequently (some say to avoid recognition, others say to seek it). We think Greensleeves, not just a change but a replacement with a purpose, is a good indication of the slowly maturing temper of the Dartmouth undergraduate's mind, an indication of a renascence in intellectual interest.

At the end of the second term, the Human Rights Society was reestablished "to foster a climate of opinion favorable to pacifism." In addition to working for a pacifist cause, the club's activities will include other areas of human rights such as civil rights.

The society is small, at present only a dozen men or so, made up of a group who have known of each others' feelings on these topics for some time and who decided to organize themselves and publicize their beliefs. Naturally, the ties of friendship being the strongest we know in college, the club's cohesiveness and strength of purpose, and thus its ability for group action, are not easily paralleled at Dartmouth by any other similar sort of organization.

However, the society is open to subscribers to its "Statement of Principles" which affirms the members' belief in the United Nations Charter, their faith in the dignity and worth of the individual, and their belief in the equal rights of men and women and of all nations.

Meeting once a week, the club plans to sponsor films and speakers dealing with pacifism, to distribute literature on the subject, and to organize library displays. It is making tentative plans for an intercollegiate conference with other college clubs.

The significance of this organization for its own purposes cannot, of course, be readily determined. Only time will tell. But its importance in the undergraduate community is another matter entirely. About one-third of the present membership are faculty members; their interests in the club will continue, we may be sure, long after the present undergraduates have left college; they will always be there in the society to stimulate its new members. If, as President Dickey put it in his Convocation Address this year, the undergraduate in the College is moving "from the ravenous animal appetites of youth to the restraints and cultivated tastes of civilized man, from a self-centered boy to a public-minded man; and with it all, hopefully, he is learning to think and like it," then this society would seem to serve an important educational purpose, one perpetuated by its faculty membership.

Recently Vox appeared on Hanover newsstands in an issue commemorating the centenary of Charles Darwin's Originof the Species. Edited by Donald W. Polm '59, the magazine was completely comprised of faculty-written articles concerning the influence of the theory of evolution upon the various academic disciplines.

This, it should be noted, was a unique achievement in and by itself for an undergraduate-staffed magazine. And in a review for The Dartmouth, Professor Maurice Mandelbaum '29, chairman of the department of philosophy at Johns Hopkins University and former Dartmouth professor, said, "The authors are to be congratulated for the clarity and conciseness of their articles." The articles' general excellence was acclaimed in Hanover as well. This high degree of quality is an additional achievement, one not anticipated necessarily, and truly rewarding.

We would like to cite the men, their fields, and their articles: George B. Saul, Assistant Professor of Zoology, "Darwinian Theory of Evolution: Scientific Aspects"; John G. Kemeny, Professor of Mathematics and Philosophy, "Methodological Problems Concerning the Theory of Evolution"; Timothy J. Duggan, Instructor of Philosophy, "Philosophy and Evolution: Some Mildly Interesting Relations"; Vernon Hall Jr., Professor of Comparative Literature, "Darwin and Literature"; Fred Berthold '45, Professor of Religion and Dean of the Tucker Foundation, "Darwinism and Religion"; and Arthur M. Wilson, Professor of Biography and Government, "Political Interpretations of Evolution."

The fact cannot be avoided that, whatever one might hope for, this sort of publication has to be a once-a-year proposition, otherwise not enough men's efforts could be coordinated into making it the excellent issue it is. But if this fact is rerettable, we should look at its bright side, at just what made the issue possible.

First, the students involved, members of The Dartmouth, had to have the interest and gumption to find out just what topics were significant in considering Darwin's theory of evolution throughout the intellectual disciplines. This inquiry demanded much more thoughful effort than most of us now in college have experienced during even our most heated arguments over evolution. Doubtless it demanded considerable independent research. In addition, these students then had to find out which faculty members had the time, inclination, and knowledge to go into the topic, as it applied to their field, thoroughly. This second discrimination required an understanding of each topic in human terms, and from that understanding a selection of the right professor. This is an educational process in itself, and the undergraduates should receive A's for their efforts, for they unerringly picked the best men for the job.

Secondly, the professors who were approached had to respond. Now, any teacher has more pressing matters than participating in a student organization, but these faculty men were willing to sit down and write out what they thought about evolution, an arduous task of mature evaluation. They showed, in effect, once again that student endeavor in an academic framework at Dartmouth will always be met with willingness and encouragement.

When such a communion of interest between faculty and students springs up outside regular course activity and then crystallizes into this last issue of Vox, we are tempted to wish something like it could occur every year, or every half-year, possibly. This coming October 19 marks the centennial of John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry. Couldn't it be possible - wouldn't it be desirable - for Vox next year to publish a Civil War issue, in which it could draw on the professors in the Economics, Government, History, and Sociology Departments? It would be an interesting and worthwhile effort.

Each of these student activities has been originated and carried through in a community of learning, in an academic atmosphere, in a setting of lively faculty interest, though of course the primary responsibility has rested with the students. No one can be sure that this resurgence of intellectual activity is due to anything more notable than the arrival of spring in Hanover (though somehow that always seems notable among undergraduates). But such activities may well have been stimulated by the new three-course, threeterm system, the first manifestation of "the new Dartmouth." If such is the case, then we may expect other activities to burgeon in the near future and may hope for a general awakening of the undergraduate body.

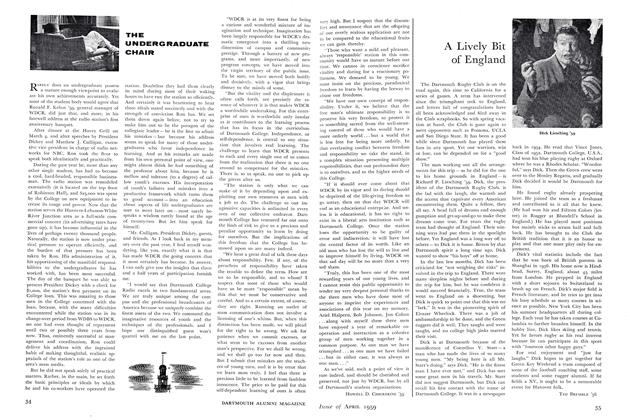

John Hessler, Dartmouth rugby captain, got an Indian war bonnet and a warm welcome from coed Nancy Dearth when the team arrived in San Diego, during the spring vacation trip to California. Dartmouth defeated San Diego State's Aztec Rugby Club, 8 to o.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

May 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

May 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureFourteen Gained — Three to Go

May 1959 -

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

May 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1959 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, JAMES LeR. LAFFERTY

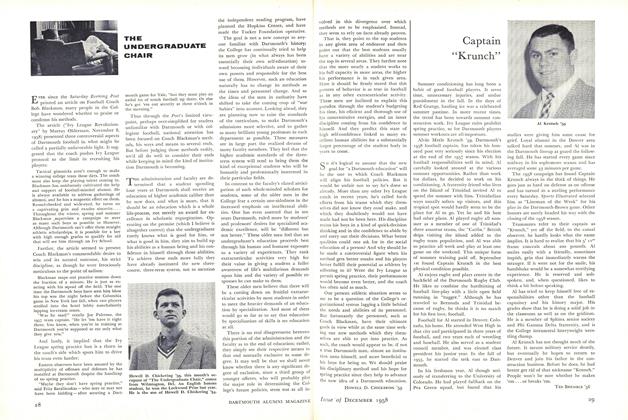

HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1958 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

FEBRUARY 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

APRIL 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59

Article

-

Article

ArticleWATERWAYS REPORT BY PROFESSOR DIXON

January, 1910 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER COMMUNITY CHORUS PRODUCES "THE GONDOLIERS"

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

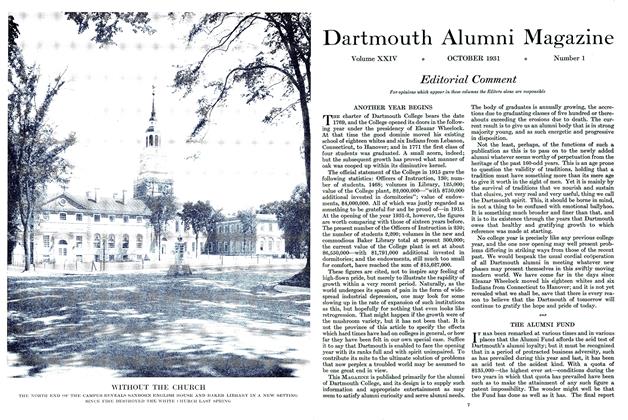

ArticleWITHOUT THE CHURCH

OCTOBER 1931 -

Article

ArticleTHE FUND O UTLA WS PRESSURE

May 1934 -

Article

ArticleThayer School News

June 1938 By Edward S. Brown Jr. -

Article

ArticleSushi Bowl

April 1993 By Robert H. Nutt '49