It is not surprising that the Mental Hygiene movement, which has made such rapid strides during the last fifteen years in social work and in mental medicine, should have entered the field of college administration. It must be remembered that college life falls in the mid-adolescent period, that very important epoch which marks the transition from boyhood to manhood, when, more than at almost any other age, mind may be said to be in the making, and the processes of life and growth are in very truth "dynamical and developmental."

This is the great period of character formation. At this age, readjustments are made with environment, especially in its relation to sex development, the emotional life is broadening into larger fields, the inhibitory power is strengthening, moral standards are being established, and the judgment, that sure index of the mature man, is becoming stabilized. At this critical period when the intellectual and moral processes are undergoing such rapid expansion, Mental Hygiene may prove of great assistance, not only in piloting the mind into safe channels, but in preventing disaster by teaching the avoidance of recognized dangers.

Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes in his "Mechanism in Thought and Morals" as far back as 1870 said: "The more we examine the mechanism of thought, the more we shall see that the automatic, unconcious action of the mind enters largely into all its processes." Mental mechanisms are established at this age with greater readiness than in later life. The individual in the adolescent stage is more impressionable. Healthful, helpful mental mechanisms underlie good habits, good conduct, and scholastic success. What are mental mechanisms ? The mind is not a jumble of ideas thrown together without sense or connection. Ideas there are but they are arranged in. groups or constellations with some reference to future use. These groups are bound or held together by or around experiences. The cement that holds them together is our emotions, our affectivity. Whether this affectivity shall be pleasurable and acceptable to the individual or the reverse will depend largely on one's early training in the home.

Hence it is very important to establish in the growing minds of the young those mechanisms that make for the ideals of life, such only as arouse pleasurable effects. Unfortunately in some cases, less desirable mental mechanisms may have been established in the home through unfortunate example or lack of proper training before the college period is reached. A home, in which the ideals of the best manhood are not taught, can scarcely help a young man when he enters the larger liberty of the college life. Mental Hygiene teaches that, by constant repetition, mental processes like physical acts become easier of performance. A part functions more smoothly by continual repeated performance of the same act. The same principle governs the intangible operations of the mind. In the end, mental processes become "organized," that is, identified with certain nerve tracts through which they seek expression, structure grows less resistant to demands oft repeated, and, in the end, the mental equivalent becomes sub-conscious or automatic. In this way, habits, good, bad, or indifferent, are formed and the mental mechanisms underlying these habits become very important in the life of the individual.

In adolescence, the prevailing emotional content of the mind exerts a marked influence on conduct. In a student body of two thousand men, there is found every variety of emotional reaction. Some are hyper-sensitive, mercurial, temperamental, we sometimes say, others are phlegmatic, calm and not easily moved. These various emotional types represent biological tendencies in cell structure transmitted from parents. When the emotion controls the personality, as when the individual's reaction is prevailingly joyous and hopeful, or depressed and easily discouraged, we say he has the corresponding temperament. One's affectivity or one's method of reaction to various issues in his environment becomes, therefore, a most important determinant of conduct.

In adolescence the inhibitory power or the power of self-control is markedly influenced by temperament. Some men are distinctly impressionable, their actions are dominated by the feelings rather than the judgment. Impulsivity with lack of judgment frequently characterizes adolescence. But by judicious training of the will the mental mechanisms of selfcontrol can be established.

Again, emotional depression is of frequent occurrence in adolescents of a certain temperament, but here again much may be done by wise counsel given at the opportune time to prevent the mind from settling into the habit of introspection and self-depreciation, and, by building up proper mental mechanisms, prevent that unfortunate issue.

The sub-conscious, or the unconscious mind, is yearly assuming greater prominence in modern psychology and enters into any attempt at character or conduct analysis. The sub-conscious mind is functioning during all our waking and many of our sleeping hours and the part it plays in the upbuilding of personality is enormous. Whether we agree with Jung in believing that the unconscious mind is constantly sending up stimuli to the conscious mind to awaken psychic energy within the realm of the conscious, or with Freud that the unconscious mind is a vast storehouse of repressed material naturally antagonistic to conscious thought, to whichever of these theories we subscribe, we do know that the subconscious mind is ever active, dominating and directing, in spite of ourselves, much of our conscious thought and conduct. This is the old "unconscious cerebration" of Carpenter, of forty years ago, modified and brought up to date by the recent teachings of Freud, Jung, and the psycho-analysts.

The remarkable influence of the unconscious upon the conscious mind, the direction given thereby to the upbuilding of healthful mental mechanisms, and the suggestions for the proper therapy make the study of the relationship between the unconscious and the conscious quite germane to that of Mental Hygiene.

Psychology recognizes two types of individuals: Introverts and extraverts, the people who are always looking in and those who are always looking out. The introverts are introspective, the individuals who always look in and not out, are not self-assertive, lack confidence in themselves, apt to take counsel of their fears, are easily discouraged, and not altogether hopeful. They are not egoistic, although they are ego-centric. The extraverts, on the other hand, are the individuals inclined

"To look up and not down, To look forward and not back."

They are always hopeful, not easily discouraged, and are always cheerful. The extraverts are good mixers, they do not withdraw by themselves and, because they have confidence in themselves, they are apt to be men with good initiative. Of course, there is every gradation between these two extremes, but these types are representative and are continually met with in the student body.

Among the introverts the following is a typical illustration of not infrequent occurrence: A. young man, quite conscientious, extremely anxious to do creditable work, begins to have a fear that he may not pass an examination. He studies long hours, does not get sufficient exercise in the open air. very likely does not get enough sleep, and. because of his fear that he will not do as well as he ought, does not relax his mental tension and fails to get the social diversion in sports and games. His fear haunts him. His conscious mind relegates the fear to the background, but it persists and finally becomes a sub-conscious conviction that he cannot pass the examination. He feels he is well prepared, thinks he understands the subject. The sub-conscious mind, influenced by the feelings and the emotions, through their subtle guidance, dominates the conscious mind at the time when the final test is offered,—the very time when the conscious mind ought to be free from any doubts. The student is not free to do his best work, cannot concentrate as he should, and sometimes, under the nervous tension, becomes confused and fails to state facts that he really understands perfectly well.

The treatment for this purely functionally fatigued state of mind, which has become a ready prey to the suggestion of fear, is revision of the hours of study, recreation, and sleep. Frequent though short diversional periods relieving the mind from protracted concentration on a single subject, thereby securing respite and rest. Mental Hygiene would still further insist that the sub-conscious, through the conscious mind, be permeated with the counter suggestion that, under the regimen described, the student can and will pass his examination.

Occasionally in persons with a sensitive nervous organization, under conditions of fatigue, ideas, entirely unbidden, protrude themselves into consciousness. These obsessions are not infrequent in the adolescent period at a time when the imagination is overactive, when volitional control is weakened for various reasons. These obsessions represent every sort of conception: fear of insanity, blasphemous language and thought, extremely repugnant to the sensitive mind, dreads, and apprehensions of many kinds.

We are familiar with the fact that train wrecks, aeroplane disasters, the being suddenly precipitated into deep water when off one's guard frequently induce a condition of nervous shock, in which volitional control and corrective judgment are so weakened that obsessions arise in the mind. The so-called war neuroses have made us all familiar with this sort of thing. But similar imperative conceptions, only less severe in degree, ma}7 arise in the hyper-sensitive adolescent mind following fatigue, loss of sleep, or other cause. These cases are perfectly familiar to any student of Mental Hygiene and yield readily to the proper treatment.

From a survey of the year's work in Mental Hygiene, it follows that consultations in Mental Hygiene should enable the student to view himself from another angle than the habitual one of his feelings, to more clearly scrutinize himself from a saner viewpoint than the distorted one of his own emotions, conveying as they do untrustworthy prejudices. The extravert with his excess of self-confi-dence, the introvert with his tendency to self-depreciation, the day-dreamer, the restless radical dissatisfied with things as they are, the occasional college misfit Who very likely was sent to college by a misguided father, the psychasthenic student who thinks he has an inferiority complex, the student, whose mind, unduly swayed by ever-changing emotions, is in a state of unstable equilibrium, the immature mind, the inadequate personality, (inadequate because of its failure to make a proper adjustment with his environment),—all these and many other personalities come under the observation of the consultant in Mental Hygiene. The chief value of the consultation lies in the opportunity it offers for intelligent prevention. By it, mental processes are guided from wrong into right channels, mental efficiency and peace of mind are thereby secured; capable students are retained and the inefficient or wrongly placed individuals are allocated to their proper environment. . In some such way, Mental Hygiene becomes a helpful coadjutor to the Department of College Administration.

CHARLES P. BANCROFT, M.D., Counsel in Mental Hygiene.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

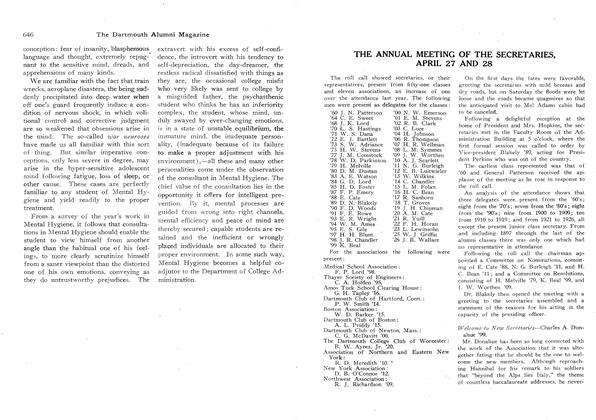

ArticleTHE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES, APRIL 27 AND 28

June 1923 By E. M. STEVENS '01, J. W. WORTHEN '09, C. E. SNOW '121 more ... -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

June 1923 -

Article

ArticleAs the Commencement season draws near,

June 1923 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

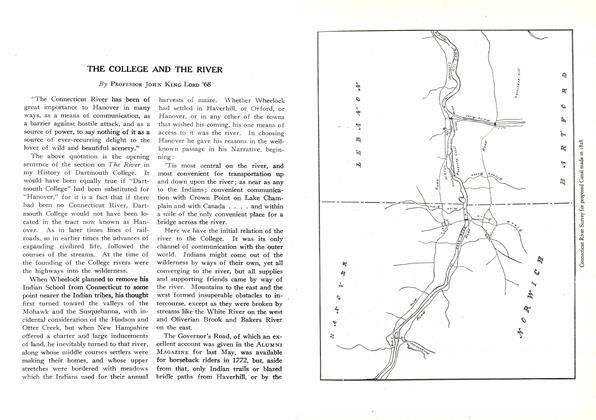

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND THE RIVER

June 1923 By JOHN KING LORD '68

Article

-

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB CENTRE IN THE VALE OF TEMPE

-

Article

ArticlePRESI DENT'S SECRETARY RESIGNS HER POSITION

APRIL, 1927 -

Article

ArticleA Fast Start

May 1953 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

October 1954 -

Article

ArticleTHE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES, APRIL 27 AND 28

June, 1923 By E. M. STEVENS '01, J. W. WORTHEN '09, C. E. SNOW '12, 1 more ... -

Article

ArticleSEA-GOING ENGLISH

March 1944 By PROF. A. A. RAVEN