of alumni the graduates of the Class of 1924, the alumni now salute with appropriate hopes the entering class of 1928—the embryonic alumni of the future. At Dartmouth, as everywhere, a freshman is a freshman; and every new class offers the delicious possibilities of a Christmas package. One never knows until one opens it what is within—but one is hopeful that whatever it is will be welcome. The demonstration rests with the package.

Unfortunately the ALUMNI MAGAZINE does not circulate largely among undergraduates, which precludes its editors from much sermonizing to the multitude thereof. The temptation every autumn is to inculcate in the neophyte laudable sentiments. Here is a new and virgin field, in which the unwearied faculty propose to broadcast much good seed. It is certain that some of it will fall upon thin soil and speedily wither away because it hath no deepness of earth. A certain amount of trouble due to tares is inevitable. But one looks with confidence to a steady increment in the good ground, from which the seed may spring to a satisfying maturity—not necessarily before graduation, but at all events during active life.

The older one grows the more one appreciates the fact that education isn't finished by the grant of a parchment embellished with mvsterious Latin verin this cynical, matter-of-fact, materialistic age of the world, when more than ever is man wise in his own conceit and rather inclined to speak patronizingly of his God.

The College aims to give men the vision as well as the capacity to fit themselves into the picture, so to speak, which human society presents at the moment. This the man must do for himself eventually —for "all education is self-acquired . . . .The College provides facilities, environment, atmosphere and influences within which self-education may be more definitely and more largely effective than it could be without them. .. .But the College cannot, if it would, transmit education on platters of silver to those undesirous of accepting it, or to those passively indifferent." Well and worthily said! What each man gets from Dartmouth depends in the last analysis on what he is willing to take. The College can help by the offer of experienced direction, but it cannot compel an obdurate mind to open. The horse may be led to water, but the drinking remains a matter of his own volition.

There was little of comfort in the President's opening remarks for such as demand that the pill of education shall be so heavily coated with sugar, or chocolate, or other agreeable substance as to be little else than sugar or chocolate. Education, if it is to have any disciplinary virtues, "cannot be divorced from the difficult and exacting." One has somehow to temper the human metal. Even more than the world has questioned the culture and social graces engendered by college education, does it question today its effect for producing stamina— mental, moral, spiritual. Neither was there much solace in the address for such as imply that there is an essential virtue in mere roughness, in deliberate coarseness, in the ethics of the cave-man, so much cried up under the comprehensive name of "red blood." Out of the strong may well come forth sweetness. The true gentleman is neither a Miss Nancy nor a boastful pugilist. He is a Man Thinking— and a Man Acting—always in the light of what he reasonably conceives to be truth.

That truth is a rather fluid concept must be admitted. It cannot be supposed to be crystallized at any given moment, so that further search is needless. Neither can tolerance for fresh experiment be allowed to weaken the ultimate power of positive conviction. It is well, while gazing about in quest of fresh truth, to keep both feet planted on the solid ground of experience before making rash steps into what may turn out to be a quagmire, or a quicksand. The College has no light task before it in fitting men to be sagacious, and at the same time duly venturesome !

"To me," said the president, "it seems that one of the fundamental purposes of the higher education is that men shall learn how to live—which is a different thing from merely existing. To live is to develop the capacity for understanding life and to acquire the ability for deriving satisfaction from it." Even so—and then, in the closing paragraphs, comes the afterthought that we must learn not only how to live, but how to live together. It isn't a purely individual concern; it is a collective one. No man liveth to himself alone; and the great need, as has been said in language less dignified than presidents are wont to use, is to know how to fit oneself into the picture.

We commend to every reader a thoughtful pondering of the President's address, which has been so sketchily commented upon above. It will repay reading, as all President Hopkins' utterances invariably do.

Incident to the opening of the college year will be found the usual announcements as to increments in the faculty and changes in the personnel of the officers of instruction; the inevitable statement of alterations in or additions to the physical equipment; the pendency of novel events and the recurrence of familiar ones. Among the latter may be especially mentioned the reunion on October 10 of the Medical Alumni, which foreshadows in all probability a closer relationship between the graduates of the Dartmouth Medical School and the great body of graduates of the College proper. Many, indeed most, of the Medical School graduates are not graduates of the College. Nevertheless their interest in the institution as a whole is very great and then loyalty unquestioned. It is improbable that any alumnus of the College proper ever thinks of the Medical alumni as alien —and it is therefore very desirable to cement and confirm the common bond which both undergraduate and postgraduate residence in Hanover create.

The College faces the most exacting football schedule in its recent history—- indeed it is unlikely that the present gruelling list of big and near-big games has ever been parralleled in the past. How it will work remains to be seen. Given sufficient stamina, reasonable luck and enough eligible recruits, it is on paper pretty nearly an ''ideal schedule"—but the demand upon the men is bound to be so heavy as to warrant a suspension of judgment before wishing that the present comprehensive list become a perpetuity. It is especially gratifying to meet both Harvard and Yale in the same year, although both must be met rather early in the season. The retention of Jesse Hawley as chief coach will command universal applause, beyond a doubt. It may be well also to remind enthusiastic alumni that while all of us hope for a reasonable number of victories, it is by no means of exclusive importance to win every game. It is much to be found worthy to contend on honorable terms with the greatest of the American colleges; and what we sincerely hope is that this worthiness may be proved, whether in defeat or victory, to our own and to others' satisfaction.

That increasingly troublesome problem, to wit, what to do about compulsory chapel at Dartmouth, has had to be met this fall by the decision (as a starter, at least) to omit chapel services altogether for a season. The institution may easily be doomed to complete and permanent abandonment, mainly because of the force of numbers too great to be readily accommodated. It remains true that the giving up of the familiar morning assemblage would be viewed with genuine regret by a host of alumni, if not by a great many undergraduates.

Much is being made of the argument that there is nothing especially religious in the attitude of mind of students who attend chapel by compulsion, although our suspicion is that this argument has no more weight now than it had in 1824. Much is also made of the alleged derogation implied in treating a service ostensibly religious as a "sort of college alarmclock." No one in all probability supposes now, or ever did suppose, that the daily chapel service required to be attended by all students had any direct bearing on the salvation of souls. Nevertheless it has about it a fitting dignity as the official vestibule to the activities of the day which we cannot overlook. Undergraduate reluctance to approve compulsory chapel, while traditional and well remembered even by the oldest alumni, can hardly be regarded as the final test or the exclusive criterion whereby to assess the worth or valuelessness of the time-honored institution.

There is. a well defined opinion that chapel should either be compulsory for all, or completely abandoned. Voluntary chapel prayers, such as many colleges maintain, reveal a discouragingly meagre attendance. Compulsory prayers admittedly have but little worth from the purely religious point of view. But the coy suggestions of the Daily Dartmouth, that something in the nature of an "intellectual chapel" service be substituted, strikes the present editors as possibly the worst alternative of all. The temptation is to urge that the old-fashioned chapel service be continued, if it be practicable with the present numbers, or else frankly given up. But if it has to be given up, many a Dartmouth man not noted for extreme piety will nevertheless feel that there hath passed away a certain glory from the earth. One may miss the inspiration, one may cherish a very vague and indefinite personal belief in matters of religion—yet we doubt that the time has come for colleges to follow without question the average family habit in its abandonment of family devotions in the early dawn. At its lowest estate the chapel requirement was a sort of personal discipline, salutary so far as it went. "A college alarm clock" it may have been, but it was a very respectable one with incidental possibilities.

Above all, why not forego the theory that this lack of any clearly religious stimulus is a novel discovery? There is just as much religious value to the compulsory morning chapel now as there was thirty, or fifty, or a hundred years ago— and just about as little. Our theological notions have suffered a sea-change; but the world has at least as great a need to emphasize religion now as it had before— and we suspect the need is increasing, rather than diminishing. Does the chapel service have any bearing on religion for the student? Of course it does—if anything does. The student may not eagerly accept what is offered, of course; but the same can be said of his compulsory mathematics classes.

It is not possible for the MAGAZINE to view without the passing tribute of a sigh the manifest tendency to consign this ancient and beautiful incident of the day to the limbo of discarded things. If that must be, it must be. But it remain's to be assured that the "must" is a sort of categorical imperative rather than a condition which exists mainly because so many wish it to.

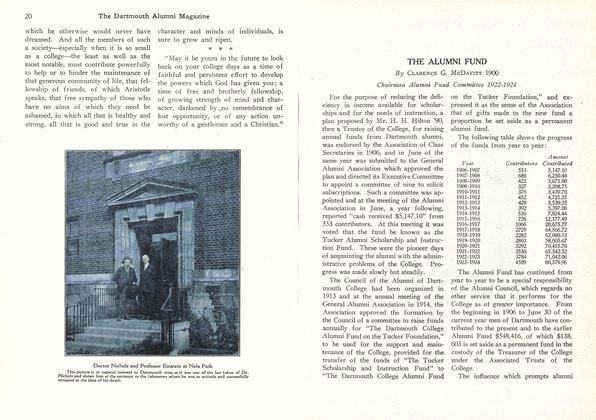

Inspiration no less than congratulation should greet the news that in last year's campaign the Alumni . Fund was brought well over the top, exceeding the quota originally assigned ($80,000) by $579.96, and enrolling as participants 713 more alumni than ever had contributed before. This achievement, due to many zealous workers under the indefatigable leadership of Clarence G. McDavitt '00, is worthy of a moment's thought and more than ordinary praise. It is not alone that this generosity enables the wiping out of the normal yearly deficit and the usual transfers to certain special funds, important as those things are. It is also important that such a record tends to make real and vital to every alumnus the annual necessity for meeting this recurrent situation, which is due to the lack of adequate endowment funds. It is probable that by this time every active alumnus of the College recognizes his gift to the Alumni Fund as a part of his personal budget, so as to reduce the labor of class agents by cordially meeting them half-way and not making it imperative to write a series of follow-up letters of reminder.

The College must command this tangible loyalty from its sons, or else curtail its scope by the reduction of its teaching force and the diminution of its numbers of students. None of us would welcome that. Many there be who feel that the time has come to question the wisdom of further expansions in size, but nobody would relish seeing Dartmouth relapse to a less splendid estate than she enjoys at present. The choice lies between making a large gift, once and for all, to a permanent endowment, or resting content with these smaller annual gifts representing the interest on an imaginary principal. The major part of this fund goes every year to cover the operating deficit, since the idea is to provide additions to income rather than additions to the principal sums representing the College estate. This year $65,738 went to extinguish entirely the deficit; and the remainder has been applied to various additions of capital as will be seen by reference to the detailed report of the Fund committee.

It is especially gratifying to learn that out of our 6000 or more of living alumni 4497 contributed this year—713 more than ever in the past. Let's hold that— and increase the number if possible. It: is properly urged that no one stay out merely because of a feeling that a small gift would not be welcome. Every gift is welcome, big or little, that represents the donor's loyal purpose to serve his College to the best of his ability at the moment. To expect 100 per cent of contributors would be chimerical, no doubt; but is it a wild dream to hope for 75 per cent ? This year's experience would indicate that it is not One mentions this matter at this time mainly because of the occasion for hearty self-congratulations on an uncommonly successful.year. But it has proved to be impossible to avoid the temptation to subjoin a bit of exhortation as well, which it is hoped the reader will pardon—and also take home..

In later issues it is proposed to consider at more length the growing importance of the Alumni Council as the agent of the entire alumni body, and to urge the more thoughtful consideration on the part of all graduates of Dartmouth of matters relating to it. With the recent alteration in the methods of choosing the alumni trustees, the alumni have transferred to the Council alone the function of presenting these representatives to the College Board. This has come about as a practical necessity. The obvious corollary is that the alumni as a whole should be exceedingly zealous in the matter of selecting for the Council delegates whose judgment is respected and whose regular attendance at important meetings of the Council will be reasonably assured. The whole alumni body is now so large and so widely dispersed that action by the townmeeting method is out of the question. Representative government is the only possible answer, and the responsibilities now laid on the Council are so great that care in providing for its composition becomes even more a duty than ever. The essence of successful representative government is that the representatives shall be adequate and worthy of the trust of those who delegate to them the power to act in their name.

On the Old Wolfeboro Road

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSOME ATTRIBUTES OF UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION

November 1924 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE ALUMNI FUND

November 1924 By Clarence G. McDavitt 1900 -

Sports

SportsATHLETICS

November 1924 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1924 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1928

November 1924 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

November 1924 By Ralph Sanborn

Article

-

Article

ArticleHOCKEY TEAM

January, 1912 -

Article

ArticleGIFTS TO THE COLLEGE DURING THE PAST YEAR

August 1917 -

Article

ArticleMemorial Funds for Dick's House

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1974 By JACK DtGANGE -

Article

ArticleMedical School

December 1941 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22 -

Article

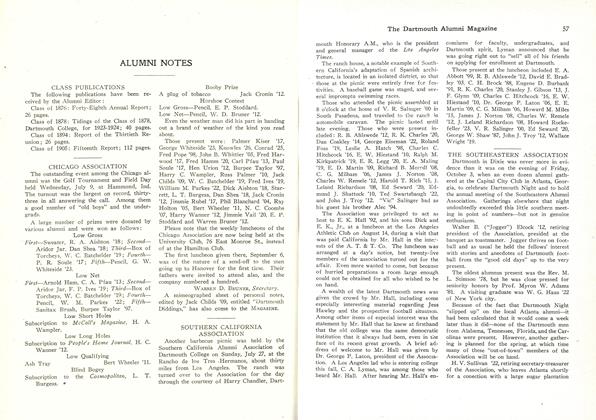

ArticleCHICAGO ASSOCIATION

November, 1924 By Warren D. Bruner