Evidently the reporter who garbled President Hopkins' speech at Chicago ten days or so ago had a taste for the dramatic. Reporters are often built that way, and sometimes what results shrieks out for justice. President Hopkins does wisely to refrain from issuing a correction for the general public, but it comes as quite fitting that the college community should understand exactly what he did say. No one connected with Dartmouth objects particularly to the possibility of having Trotzky on the faculty, but since President Hopkins didn't suggest a step so far removed from the conventional path of college instruction, The Dartmouth is glad to be able to publish his correct statement.

But what if he had suggested that Trotsky be added to the faculty? If ever there existed a fear complex upon the part of anyone, here it is in this sniffling, haunting worry over the possibility that American undergraduates may hear the actual facts of life from those who are manipulating them. Apparently the American college should nurse its infants only with the Nestle's Food of 100 Per Cent Indifference to Life. Apparently its chief job is to shoo off the wolves of discord while the lambs of conformity are petted and idolized and thrice blessed. And whatever you do, don't let the undergraduate hear the other side of the story ! Poor boy, it might hurt his sensibilities! Much better let him play his innocent games, read his harmless books—and swallow everything whole. Undergraduates are so immature, you know, and so unfit to see the seamy side of things! Of course! But President Hopkins disagrees and he has disagreed so persistently and so efifectively that The Dartmouth takes this occasion to republish a portion of a speech which he delivered a little less than a year ago before the Alumni Association of Chicago in which he came -out unequivocably for com- plete freedom of speech before undergraduates: "I have seen at the gates of the steel works in Pittsburgh; I have seen back of the Baldwin Locomotive Work in Philadelphia; I have seen in the street of Schenectady; I have seen here at Hawthorne men pour out and go down the avenue after the day's work; and on every corner I have seen the soap box orator holding forth on the theory of this, that, or the other thing. I have seen young men of 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20 years of age as well as elders sitting down and listening to these things and then going off into the saloons or somewhere else and discussing for hours the propositions set forth. The man outside the college is not isolated from this. The man outside is not protected from it. On the other hand, the man outside is subjected to the presentation of a lot of asserted facts and a lot of reputed data which somebody has got to disprove in future times, or allow him to accept these as truth.

"Do you and I, we who are parents or who are alumni of Dartmouth College, desire that our sons shall go into the College and shall be by fallible men told uncertain facts in regard to changing situations, and turned out with the belief that they are possessed of final truth? Are we willing that our sons shall go out handicapped as they would be if they had never learned anything except the conventional and the ortlidox doctrines which might be presented to them ? Somebody says, 'But is not this dangerous?' It may be. But any other policy is infinitely more dangerous!"

The issue now as always is not whether a particular person is to be hired to lecture to or teach American undergraduates. The issue is whether American undergraduates are to be given an opportunity to hear all sides of a question. Thank God that at least one college president let's it be known that he at least demands freedom.

The discussion was apparently brought to a formal close by President Hopkins, March 8 in an interview given out in New York just before he sailed for Europe. We quote here the interview as reported in The Nezv York Tribune of March 8:

Dr. Ernest Martin Hopkins, president of Dartmouth College, who said recently that Trotzky, if available, would be welcomed to explain Bolshevism before the 2000 students of the college, replied yesterday to criticisms from the American Defense Society that his utterances "might well have been inspired in Moscow."

Upholding his educational theory that students should be given opportunity to form their own opinion, rather than "to be taught what to think," Dr. Hopkins made public an answer he had sent to a letter of R. M. Whitney, director of the Washington bureau of the American Defense Society.

In an interview at the Hotel Vanderbilt, Dr. Hopkins explained that by offering to permit Trotzky to speak at Dartmouth he did not intend to imply that he agreed with the Bolshevist leader, but that the forum of the college would be thrown open for discussion, just as it was in the case of William J. Bryan, who spoke there against Darwinism.

"And I am convinced that Trotzky would make no more converts than Mr. Bryan did," said Dr. Hopkins. "Ever since Mr. Bryan denounced the Darwinian theory of evolution before our college there has been a reawakening of interest in the subject. We have more students pass successfully in their studies of evolution than before Mr. Bryan spoke." Expressing incredulity that Dartmouth would permit Trotzky to speak, Mr. Whitney wrote to Dr. Hopkins: "Those of us who still believe that we have a form of government better in every way than that advocated by Lenin and Trotzky had hoped that the directors of the studies of the minds of the youth of America would be careful of the material they fed the immature minds of the coming generation.

"For nearly two years I have made a special study of the Communist movement in the United States. This study has proved to me conclusively that such remarks as those credited to you could well have been inspired in Moscow and are in strict accord with the well-matured plans of those who would overthrow this government by violence."

Asserting that his desire was that Dartmouth should stand for freedom of speech and thought, in the belief that "we should be unafraid that harm could ever come to us mentally, spiritually or morally by the preservation of those liberties," Dr. Hopkins, in his reply, said:

"Of course, the fact is—and I have heard this said within the last few days by some very practical men of large financial and industrial responsibilities, that the corruption and acquisitive self-interest revealed in the Teapot Dome investigation make more Bolshevists in twentyfour hours than all the agents of the Soviet government could make in years. Yet here again I believe that before we get done we shall all wish that we had a people more judicially minded and more capable of distinguishing between truth and error than we have at the present time."

"What would be the effect on the students of listening to a speech by Trotzky?" Dr. Hopkins was asked.

"The effect would be about the same as the effect made by Mr. Bryan. The students, who think for themselves would soon see that he was prejudiced and they would be more likely to disagree than to agree with what they heard. They saw that Mr. Bryan was prejudiced against Darwinism. The result was they became converts to Darwinism.

"Our great danger in this country is in trying to coerce young minds into a stereotyped form of thinking instead of teaching them to think.

"It is all nonsense to think you are going to train youths to be good Americans by withholding facts from them, or by presenting them with only one side of the case. I have found that the surest way to convert a student to radicalism is to let him listen to a capitalist propagandist, and the surest way to convert him to capitalism is to let him listen to a radical propagandist. Propaganda is the great evil. Truth is the thing most needed.

''That is the trouble with the Teapot Dome investigation. It is being used for political propaganda. We have been worked up into a hysteria about it and can see only scandal. What we need to see, if we are to profit by the investigation, is the truth, whatever that is."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

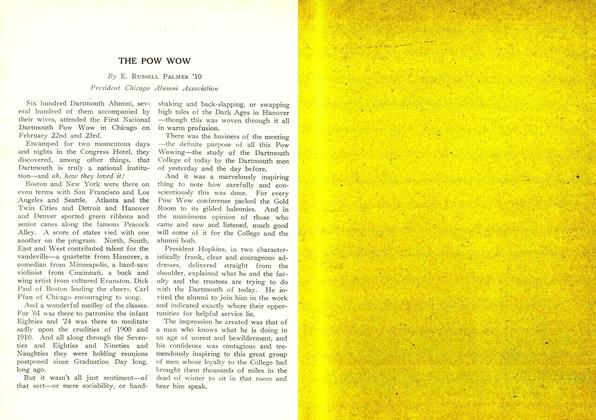

ArticleTHE POW WOW

April 1924 By E. Russell Palmer '10 -

Article

ArticleIS THE COLLEGE EDUCATIONAL PROCESS ADEQUATE FOR OUR MODERN WORLD?

April 1924 By Charles Dubots '91 -

Article

ArticleThe Chicago Pow Wow which

April 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

April 1924 By H. Clifford Bean -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth