[Doctor Stuff]

My memory of medical education at Dartmouth comes from a beginning fifty- five years ago. But the first chapter relates only to undergraduate misconceptions, blood-curdling curiosities, rowdy medics and lectures by a foreign professor in which extraordinary smut was fed to us instead of frank and useful information. So to avoid prejudice and inaccuracy I will discount about fifteen vears.

Along about 1880—a few years more or less make no difference—some surgeons who had learned their art in the wild days which went before chloroform and ether were pointing with pride at their records for speed. Lister ism, the antiseptic method of operation which was to revolutionize surgery, was slowly gaining demonstration and favor, but had not yet prevailed. I had seen, a year or two before, the first operation under carbolic spray in the amphitheater of the great Cook County Hospital in Chicago. And I had seen it fail spectacularly because someone neglected to recall the affinity between ether vapor and a naked flame. The ordinary surgical clinic differed only iiom the operations of a plumber and his assistants on a hot day in that the things the surgeons worked upon gave signs of consciousness before and after. A kindly clinical teacher might encourage his assistants and a nearby student or two to insert their dirty fingers in a surgical wound to gain exploratory skill, and himself feel the warmth of a meritorious deed.

Only a few advanced states—and New Hampshire was not one of them—provided lawful ways to obtain the cadavers for dissection. But medical men must learn the structure of the human machine before the}' attempt to make repairs. And for ways that were dark and for tricks that were (frequently) vain the anatomy prof was peculiar, which the same I would rise to maintain.

Notwithstanding Florence Nightingale and her good works the trained nurse was still a rather startling innovation in the larger cities.

One year of alleged study followed by two courses of lectures—the same lectures repeated or taken in different schools—with dissection and the passing of surprisingly loose examinations were the general requirements for a degree in medicine. Laboratory and practical courses and clinics were little required, though frequently offered by progressive teachers. With such easy entrance to the most difficult and the most responsible of professions many incompetent doctors were loosed upon an indiscriminating public. For this and doubtless other reasons the average expectation of life was then about twelve years less than it is today.

It must be remembered, however, that the men who sought excellence found it; that the objects of study—human ailments—were ever present; and that the writings of the most progressive were available for all who were ambitious enough to want them. The most learned and skillful became the teachers of the doctors of today.

This was a period too in which many superficial and inaccurate observers saw in the busy medic only a noisy unclean pest, who with a fresh shirt in one hand and a diploma in the other, a visible stethoscope and a pocket full of pills and powders, suddenly sublimed into the clever young doc. and in due season into the good old family physician.

Any one familiar with medical education knows that for many years the one subject of accurate, intense and thorough study (though other subjects might be studied well) was Anatomy. The professor knew his business and made a test of his subject; and for a long time dissection was the only laboratory course. There was a fascination in reeling off the sonorous Latinized terminology of the neatly arranged organs of the hum,an body that caused in every medical initiate the longing to be a good anatomist. Think of having a Hippocampus Major in the head and a Pronator Radii Teres to flex and extend at will as soon as one knew where it was ! "Don't mind your Chemistry." How often that was quoted to me from some of my colleagues in the earlier years of my teaching! "Chemistry is no use anyway", said the student. And he was right as it was taught, as it had to be taught. A few lectures and no laboratory work, or the minimum of elementary fumbling was all the student got. If he could pass the ABC's of chemistry and glibly supply a few formulas of no more value in themselves than the spelling of c-a-t, he never wanted to hear of it again. And yet he was going forth to aid the most complicated chemical machine in the world to do its work aright. The time was not ripe. The older practitioner knew no valuable chemistry; it had not been brought into practical form for the student; it had not found room or place in the course; and it was difficult and useless to the student who met it for the first time in his medical studies.

Today the medical student before and after taking up his professional study carries his chemistry over at least four years, largely in the laboratory, to the point of pleasure in the aid of so farreaching ah instrument. He can do, or if his time is otherwise employed—he can interpret, complex .analyses, read intelligently and apply monographs in organic and physiological chemistry, food and diets, air and water, disinfectants, toxines and the poisons of industry. And the art of the student of internal medicine is improving now almost as rapidly as has surgery since the introduction of antiseptic methods; though material from the research laboratories has accumulated ahead of his application of it even now.

The Dartmouth school, though under the authority of the Trustees, was, for all practical purposes, a proprietary school, maintained by a division of the scanty fees; and it would not have been possible to secure lecturers of the highest ability had it not been for the attractions of a Hanover summer and of a session which at its longest continued from the middle of July to Thanksgiving, thus allowing those who must return to metropolitan engagements to give their lectures in the first half.

A private recitation class was maintained for about twenty-seven years, at first by the Doctors Crosby, but during most of the time by Dr. Carlton P. Frost with other resident medical men. This course was not counted in the requirements for a degree, but was of so great educational value that it grew almost to equal the lecture course in numbers, having ninety-six in it when it was last given in 1896. And in noting the progress and success of Dartmouth medical graduates great value must be placed upon the winters and springs in this solid work. In 96-97 the lectures and recitations were merged into a graded four-years' course. After 1914 instruction in the last two years was suspended by- the Trustees, mainly for the reason that the College, notwithstanding the genuine nature of its work and the excellent record of its graduates, could not at that time meet the quantitative clinical requirements established by the Committee on Education of the American Medical Association.

For a long time—l write of nothing more recent than a quarter of a century ago—the Dartmouth medic was looked upon by many as an outlaw going about his ghoulish work by day in clothes for which no purchaser on the street corner would offer thirty cents, spending his nights in dissipation, and responsible for all the anonymous noise and mischief of the place. Nothing could have been more unjust than such a generalization. He was often poor, and for that reason perhaps a little defiant, but he was generally an irreproachably regular, attentive and diligent student. There were occasional exceptions who were "taking a college course" by wasting their time more liberally than was possible under a monitorial system. Now and then men who had been dropped from the academical college entered the Medical School, perhaps to avoid going home. And on certain special occasions the payment of a matriculation fee of five dollars for some athlete was considered worth the money. These occasions were rare and usually unprofitable. The genuine medical students who played upon teams as late as 1894 have made honorable places in their profession in nearly every instance.

(Dartmouth came to strictly undergraduate athletic teams several years before much larger institutions ceased playing men from their graduate schools even when they were graduates of other colleges.)

The order of a medical school was selfregulated and peculiar. The jovial medic, cramped and constrained during a long morning spent on the hard seats of the amphitheater, had a way of easing joints and nerves before and after lectures by singing, stamping and the most boisterous horse-play, sometimes passing a man up from the lowest tier of seats to the top with shrieks and howls of artless glee; but the minute the lecturer entered the room all noise stopped as though the sportive crew had been changed to stone, and no body of men could have been more quietly attentive. One jocund act perhaps encroached a bit, but it had salutary qualities of discipline. When a student arriving late had the hardihood to descend to his seat in attempted stealth, feet all over the room beat time to his soft steps, and when he placed his anatomy upon his chair a deafening crash marked the instant of contact. The effect was ludicrous in the extreme and few men made a second attempt. Other disturbance was unknown, and the hour was always the lecturer's opportunity, though his audience was quick enough in recognizing whether he was giving value for their time.

For many years our Medical Commencement a few days before Thanksgiving was one of the high festivals of the College. The medic burst his shell and appeared as the young doctor in his go-away clothes before a large and admiring audience. As he roomed outside the college buildings and was democratic in his social life and amiable in tying up cut fingers and administering cathartic pills he had many friends. Here too the senior delegate from the medical societies of New Hampshire and Vermont gave out that wise advice so little varied from year to year. In 1806 Dr. Nathan Smith said in his valedictory address to the class, "You have not finished your studies. You have only laid the foundation for them, on which to build must be the business of your future years." And this in substance was repeated every year and continued sound and true.

But before the triumph came the final trial—the examination by the delegates. Two delegates from each medical society arrived a day before the graduation exercises and were comfortably lodged in the "Hotel Frary." Escorted by that most efficient high priest of the solemn occasion, Dr. C. P. Frost, they established themselves for business in the little anteroom of the medical building where were the ancient grained-wood furnishings, the store of retorts and alembics dating back almost to the days of Lavoisier, the railroad on which the little car ran to the turn-table in the lecture room carrying "the oxygen gas and the hydrogen gas and all the gases" or dismembered cadavers, the fifty years-old smell and the excitable little cast iron stove,—four doctors of dreadful keenness, watchmen at the gates of Practice. With them were Dr. Frost and the writer, occasionally Dr. L. B. Howe when he could be lured back from his patients at Manchester, and a little later Dr. William T. Smith. They argued among themselves in an amiable way for choice of subjects, and finally agreed. No one pounced upon Chemistry but they generally poked it off on the youngest delegate.

The victims were brought in according to the alphabet, and, until too much efficiency prevailed, one at a time, to whom all could listen. Later the methods of the concourse prevailed and each doctor had his prey—each lion a Christian so to speak—who rotated at the tap of the bell. The touch of the examiner in Chemistry was light, and if the candidate could give the formula for water and for salt, tell some difference between the chlorides of mercury, and perhaps satisfy the examiner that he could make a test for albumen or sugar he passed as armed enough in Chemistry, much to the grief of the teacher who found it difficult indeed to advance his standards while so little knowledge would satisfy the professional demand. Unless the inquirer into anatomical knowledge had refreshed his own slipping memory and was posted to the minute he found the candidates ready for his worst. And Ptiysiology seldom offered obstacles. But you may be sure that the instruction in Practice, Surgery and Obstetrics was well explored, as was to be expected of busy practitioners who wanted to know the latest doctrines. The occasion was intimate and in retrospect agreeable, though at the time it suggested too much the intimacy of the surgeon or the dentist. But the best students were as well-prepared and ready then as now, and it was a pleasure to hear the learning flow forth. The v@te was usually prompt and unanimous and was announced at once to the little group of waiting letters in the lecture room, and it was some times received with significant applause. In truth these examiners were a mild and kindly folk, and if the neophyte had passed the faculty who were they to turn him down, even though he stammered and blundered in their terrifying presence.

But candidates for a degree who had not met the faculty requirements were, under certain conditions, allowed to try their luck with the delegates who in these decisions found their most responsible duty. Practical cases resolved themselves into two classes,-—that in which most of the faculty wanted the candidates to get a degree, but as they could not quite give him the technical credit they "passed the buck" to the delegates; and that in which the candidate and the faculty held conflicting views. The delegates were generally a wise and dependable jury and met both cases with discretion.

The condensed story of Dartmouth Medical School would be of quiet steady work, of the going forth of graduates well qualified according to the standards of their times, and of an after history of these growing with advancing knowledge. But such records lack the news features of the exceptional and fantastic. Some strange stories can be told since they harm no one now. 1 write only of what I know. Others could tell more.

A trifling matter is the wandering skeleton. In all schools of medicine aa articulated skeleton hanging from a standard is the right hand man of the professor of anatomy. There was a period when this useful relic had the habit of disappearing from his normal habitat and of greeting a different world from aloft in the Old Chapel or in the president's chair. And sometimes freshmen found themselves immured in the ancient crypt called a dissecting-room much to their distaste. They favored the version of the Latin aphorism which comes into English "Nothing good of the dead but their bones." (Nil de mortuis nisi bonum.)

But there have been less playful affairs.

Once upon a time more or less than thirty years ago, a citizen of whom Norwich was not proud died and was buried late in the fall of the year. Soon after, a fraternity banquet was held at the Norwich Inn at which two of the serving assistants were medical students capable and enthusiastic in their work. Let them be known as Wise and Bright. It was a time when material for dissection was scarce and expensive, and it occurred to them that their late return to Hanover with a wagon at their disposal would offer fine opportunity to secure an inexpensive cadaver which would never be missed. Accordingly in the late hours of the night with a light snow falling they exhumed the Norwich citizen and dragged him across the field to their wagon. But now interposed the unexpected which so often baffles human plans. It ceased to snow, and the noisiest of modern advertising devices could not have shouted louder than did that trail from the grave to the wagon. Indignation burst forth from Norwich, I suspect not so much at the loss of its defunct citizen as at the idea of a foray from Hanover; and in a very short time Mr. Norwich was located in the cellar of the medical building by the attorney of Windsor County. A trial followed at Woodstock and the astounding fines of $2OOO. and $l5OO. were imposed as prescribed by the law of Vermont. Wise was able to manage his fine, but Bright had to go to jail, from which he was redeemed by the faculty of the medical college on the security of a life insurance policy which has since been paid. I suppose it is unbecoming to show any tolerance of an act so plainly and expensively unlawful, though common enough when medical students had to learn human anatomy if they were going to be capable doctors, and yet without legitimate anatomies to study. But this was the comment of a well known citizen of the outraged town, "I don't see what they are making such a fuss about that grave-robbin' business for. If somebody had jest come over to Nor-which when the old cuss was alive and knocked him on the head and taken his carcass over to Hanover, they aint a pusson in Nor-which would uv said a word".

And this affair had a strange appendix. I have before me a pinky-brown circular, 8" by 12", almost a handbill, which came to me from New York addressed in a characteristic and cultivated hand, and also some clippings from metropolitan journals. The headline of the circular is, Crimes and Criminals of Dartmouth Medical College". It mentions several names, and after a cleverly circumstantial attack on the school announces the early publication of a book with the title given above, in a free edition of 25000 copies.

A year after the Norwich misadventure a mature and apparently well-educated man was a candidate for a medical degree. But he was an inadequate student, and as the end of the term came near it was evident that he would never make the grade. So he attempted to force the granting of the degree by investing himself with a sinister and mysterious power. He was a puzzle never quite solved. He was a dull student, but his methods of attack combined elements of adroitness and of lunacy. He had the manners of a gentleman, but not his principles. And he showed very poor judgment in bringing threats to bear upon the secretary of the Medical School. Although he signed his name freely to his newspaper correspondence, let him be known now as Mr. Darke.

I was present at one of his interviews with the secretary. His bearing and language were unobjectionable, and he was never definite enough in his threats to convey an exact meaning. He attempted to give the impression that he was clothed with great though nebulous powers. We were at liberty to infer that he was an emissary of the federal government. But, he said, he could take no action which would be injurious to a school of medicine whose degree he held. It was only a solemn warning that he was giving. But his tactics were of no avail, and he did not pass the faculty examinations. As a rather special and peculiar case he was allowed to come before the delegates who rejected him unanimously.

He left Hanover at once with a sour mind. In about three weeks the pinkybrown circular was distributed. The secretary of the school received with his copy a letter from Darke in which he stated that he would suppress the publication of the book if he should receive his diploma and be recognized as an alumnus of the school before a certain date which was very near at hand. Darke also managed to get into a leading New York paper letters which so plausibly stated a fictitious case that even shrewd newspaper men were somewhat misled. I wrote to an acquaintance 011 the staff of the paper, in which I saw the letters, giving the facts, and received the reply that they had come to the conclusion that Darke was a liar, but that they did not wish to exploit him further unless he made more noise;—if he did they would nail his scalp to the office door. Whatever the reason, Darke subsided, and the 25000 edition of Crimes and Criminals of Dartmouth Medical College was never published.

And to this appendix a little tale was attached. In his correspondence with the secretary Darke sent a copy of a sworn statement which he proposed to spread abroad as widely as his book. And this was the substance of his affidavit,—that on a certain specified day and hour, in a certain room in the Dartmouth Hotel, Dr. Goodwin (only the names are fictitious), a professor in the Medical School then, and dead at the time of Darke's accusation, had for the sum of one thousand dollars well and truly paid agreed with said Darke to deliver to him the diploma of said school at that graduation for which Darke had in fact been rejected. Now Dr. Goodwin was a man of integrity and no one who knew him would give any weight to such a libel. But it was an unpleasant story to float around and some of those who love such scandals would surely give it credence. It is difficult to prove a negative, and so the matter rested. As a matter of fact the charge was never made public and was known only by a few. But several years later the doctor's sons in looking over some old papers came upon a memorandum book or little diary in which was the substance of the following, "Went to Worcester to visit sister Helen. Took Tom with me." And the date, now easily verified, covered the time set in Darke's affidavit and several days before and after. It is difficult to fit a spurious event into consistent circumstances.

There was a time when Dr. Carleton P. Frost was the only physician resident in Hanover; and how that excellent man met the responsibilities of administration, teaching, practice, consultation, attended to the babies and kept a watchful eye on civic affairs is a marvel. Now twelve doctors of Medicine are living here engaged in practice or in teaching.

The small hospital equipped to encourage the best in medical and surgical skill, the nurse trained to furnish care which the doctor gave formerly if it was given at all, the automobile, swift to permit a call ten miles away and return within an hour or to reach an emergency distant twenty miles in half an hour, have so changed the conditions of rural practice that it is a wonder that more have not yielded to the enticements of country life and made other places as favored as this is.

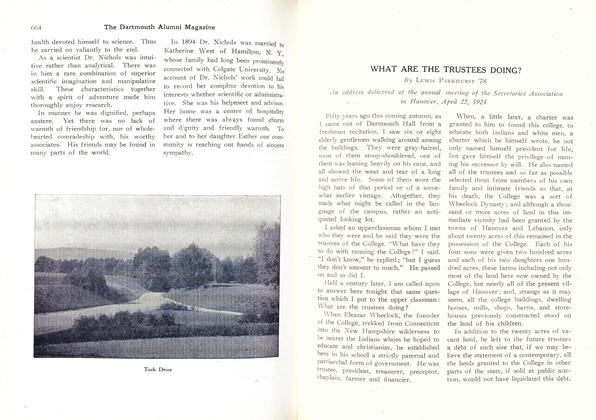

Medical Building after alterations in 1873

Dr. Dixi's Hospital, opposite Medical Building

Dr. C. P. Frost

Dr. Dixi Crosby

Dr. Frost and class in Anatomy, 1871

On the trail near Hanover

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT ARE THE TRUSTEES DOING?

June 1924 By Lewis Parkhurst '78 -

Article

ArticleSaturday Morning Session

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleThe Responsibility of the College to its Alumni

June 1924 By P. S. M. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

June 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Article

ArticleERNEST FOX NICHOLS

June 1924 By Professor Gordon Ferrie Hull

Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

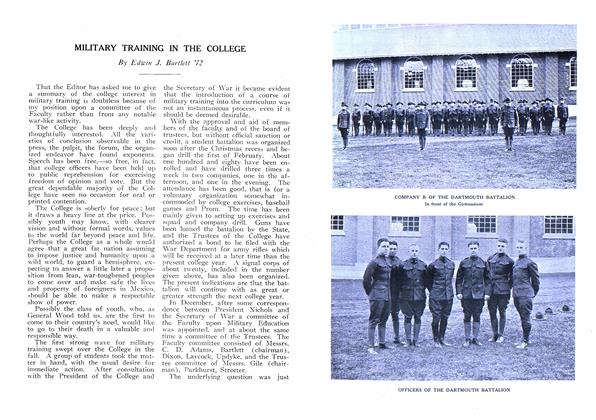

ArticleMILITARY TRAINING IN THE COLLEGE

June 1916 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

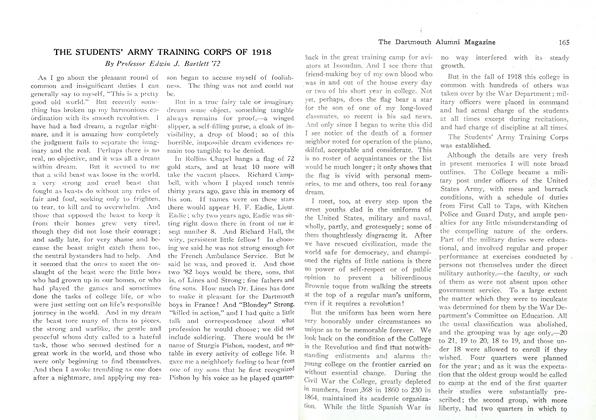

ArticleTHE STUDENTS' ARMY TRAINING CORPS OF 1918

February 1919 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

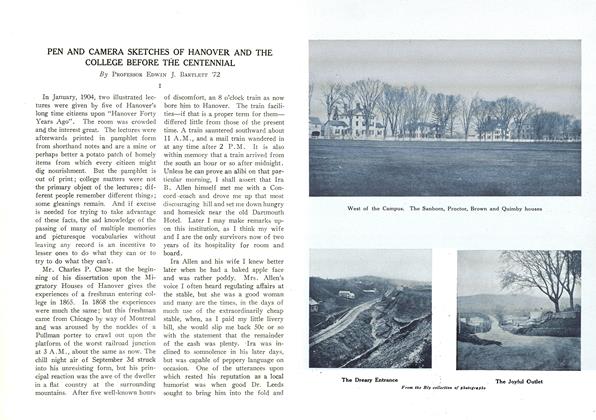

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

December 1920 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

May 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August, 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72