A Paper Read at the Annual Meeting of the Secretaries

As one who has waxed more or less garrulous during the past two or three years concerning the responsibility of the alumni to the College, the writer of these lines feels a certain hesitancy in approaching the reverse aspects of that problem. Beyond doubt there is a reciprocal responsibility on the part of the College toward its graduates, but very possibly it is not for the alumni to attempt a strict definition of what it is, or seek to fix for it metes and bounds.

Indeed it was with this in mind that I made bold last winter, when the idea of this discussion was first suggested to me, to ask President Hopkins to give me a lead, confessing that as a matter of first impressions the subject had caught me without very definite ideas. He said at once that in his view the first and most obvious responsibility of the College toward its alumni was "to keep on being a good college."

We are told to beware of easy answers to complex questions and I suppose, onthat theory, I should beware of this. Nev ertheless the more I consider it, the more I am convinced that it sums up the case as well as it can be done. The only defect, if there be a defect, is that it leaves in the air the decision as to what constitutes a "good college'*—more especially a good college as viewed by alumni of various ages, contrasted with the views of trustees, college officers and students on the ground. Do we even mean that it is the duty of the College to satisfy the alumni of its essential goodness by consulting their ideas thereof ?

To be sure, the alumni are asked to assist materially in paying the piper and their natural propensity is to assume a right to call the tune. Is the College obligated to heed? To some extent, no doubt, it is—provided the requests from the floor be for the appropriate music. To some extent, I suspect, the duty of the College is to resist alumni pressure, as a part of its inescapable responsibilities to the alumni themselves, in its effort "to keep on being a good college.' No small portion of the duties which every such institution retains and should perform relate to a sort of informal postgraduate instruction, operating on the mass of alumni in such a way as to inform its taste, disinclining it to demand the sort of things it should not. In other words, I conceive it may be part of the college duty to lead the alumni to know a good college when they see one. The thing they might consider a good college, if left entirely to themselves, may not be what they ought to consider to be such.

Alumni bodies, we must remember, usually cover a long stretch of time and a protracted period of experience, during which there must almost certainly occur several changes of taste and more or less alteration of standards. Such bodies are prone to be distinctly critical, and the critical apparatus is liable to be either insufficient or inaptly applied. It is no easy task to satisfy something over six thousand men of widely different ages, widely different theories, widely different environments, and with college traditions which relate to the long space of years between the Civil War and the Treaty of Versailles. So great a company of individuals is sure to demand conflicting things. Some will hail with unbounded delight a great increase in the enrollment. Others will deplore the increase and demand that numbers be sternly restricted. Some will insist that it is of primary importance to insist on a high scholastic standard, where others will bitterly denounce any course of conduct which impairs the prowess of athletic teams by ruling off men who are delinquent in their classes. Some will deny that to be a good college requires any attention to the ancient classics. Others will go to the stake for Greek and Latin as the quintessential sine qua non. Some will advocate more graduate schools; others, fewer graduate schools. In fine, the alumni of a college may be depended upon to demand every sort of contradiction imaginable; so that striking the balance is no light matter for the president, trustees and faculty, in whose hands the actual responsibility vests.

\\ hatever the College does is likely to be dead wrong in the estimation of some devoted group. If it countenances Liberalism, it infuriates the Fundamentalists. If it pleases the Fundamentalists, it awakens in the Liberals a withering contempt. If, by stern scholastic requirements, the College produces a losing football team, it arouses the bitterness of alumni who wish above all else that Dartmouth shine in the sporting page. And yet, somehow or other, the president and his fellows must so manage that, in the general estimation of mankind. Dartmouth shall go on being a good college. I do not envy the president this task—but I hasten to add that, as far as he has gone, he seems to me to be succeeding to a marvel. There are very few, I am convinced, for whose opinion there is general respect who would question the statement that the Dartmouth of today is an uncommonly good college. I think, indeed, that most would say it was a better college than in their own remoter day.

Therefore I would amend a trifle what President Hopkins said in this matter. The responsibility of the College to its alumni is not alone to "keep on being a good college," but also to make its alumni recognize a good college at sight. Its details are bound to differ from decade to decade. The good college of today is bound to be different from the good college of thirty years ago. And its goodness consists, not at all in satisfying exigent alumni in matters of detail, but in adapting itself so accurately to current conditions as to serve current purposes. That is a good college which serves well its day ; and to that end the energies of its directors must be bent. Those directors cannot in all things satisfy' all alumni whims and if they attempted to do so would probably end by satisfying no one. Their responsibility to the alumni is fulfilled when they fit the College to its appointed tasks in the world that' now is—and when they make it perfectly plain to the graduates that this is what they are doing.

Rather fortunately, perhaps, there exists in every alumni body a predisposition to applaud. One is not unduly critical of one's parents, more especially of one's mother, and the college's relation to the graduate is traditionally maternal. There is a reserve stock of pride in one's college allegiance that operates as a sort of levamen probationis-—as the lawyers would say—making it less difficult than it might seem for the college to commend its courses of conduct to those who have gone before. If the institution is seen to be maintaining its standing before the world; is holding its own, or still better gaining ground; if it is spoken of by the generality of people with respect and esteem, there is no question whatever of lukewarmness in the alumni body. If the new Dartmouth presents a somewhat amended curriculum, if its policies differ from those in vogue in our earlier day, which of course they must, the alumni will nevertheless follow enthusiastically on. It may not be, and probably will not be, the sort of college they were accustomed to in prior years —but they behold that it is very good, and they may be depended on to cheer. In short, if the college succeeds in being a good college, every one is quite certain to know it in the end. If it fails, that also will be known. And the responsibility of the institution to its graduates is to attain success, avoid failure and command the acclaim of mankind

This amounts to saying that the criticisms, when they occur, are likely to be individual rather than collective. One speaks of the alumni as a mass, as an aggregate, rather than of the alumnus, as a single unit. There is no possibility of formulating responsibilities in general terms for the satisfaction of the individual graduate, although beyond doubt such responsibilities do exist and will presently be touched upon. The main job is to justify the collegiate existence as a vital force for good in a given era.

The incidents of this task are several and seem important. The most imperative of those incidents appears to me to be the constant endeavor to make the College real to its more distant sons. We, who are not in immediate contact with the institution, know far less about it than it is desirable we should know. We are forced to judge of it by what meagre fragments we may obtain at annual alumni dinners, at infrequent class reunions, or from chance meetings with those actually engaged in work on the ground. Much more is done now to bring the College to the notice of its scattered children than was done in former years. It is a responsibility to which the College is evidently alive. Where the president on his winter pilgrimage through the country was content in elder years to speak before eight or nine large alumni associations, he must now appear before a score; and in addition, so far as possible, appear less formally before smaller groups here and there. Actual visitation, somewhat reminiscent of the oldtime pastoral call, is still in all probability the most important single agency that exists for keeping the alumni in touch with Hanover.

Now alumni are as a rule busy men, inclined by necessity to make their love of Dartmouth a thing apart. It is only the rare instance of the "professional alumnus" (as I like to call him) in which that love can hope to figure as the whole existence. And yet wherever a Dartmouth graduate abides, there is some part of Dartmouth College, latent most of the time, but still inwardly glowing. It is the College's responsibility to see that this spark does not die but is periodically kindled afresh.

For most of us, it is to be feared, there is a tendency to make a rather perfunctory perusal of such literature as the College sends forth to enlighten her sons. Nevertheless an honest effort is being made, partly through the ALUMNIMAGAZINE and partly through the informative bulletins of Mr. Larmon, to make the College a reality to widely dispersed alumni. This is entirely novel. Nothing like it was dreamed of in the Old Dartmouth. It represents an effort to keep the alumni in constant and conscious touch with Hanover, and above all to do something more than approach the graduates for further contributions of money. Nothing more justly irritates the average alumnus than to feel that the sole interest which the College has in him is centred on his pocket-nerve.

In the nature of things, requests for financial support cannot be avoided—but they can be supplemented by. more pleasurable instances of contact and in this regard the responsibility of the College is, I think, manifestly recognized. The discovery of new and pleasant ways for the furtherance of a personal relationship affords a labor of incalculable importance and it is gratifying to note that the administration has so frankly recognized this phase of its duty. I make no mention of the reciprocal duty of the alumnus to respond. That is part of the alumni responsibility to the College—not of the College to its alumni. The utmost the College can do is strive to awaken the intelligent interest and enthusiastic zeal of its graduates.

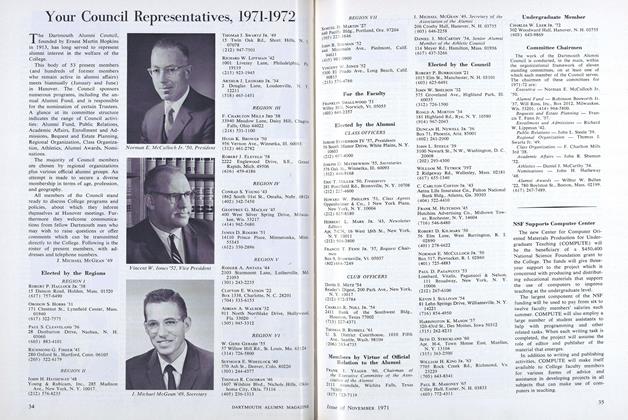

It is impossible, I think, to overestimate the importance of the annual gathering of the class secretaries at Hanover as probably the best of all the available channels for making the College known to its alumni. I have heard this meeting repeatedly cited as the most vital one in the whole calendar for the dissemination of information concerning what the College is doing. That meeting brings together every spring representatives,of almost all the active classes, from oldest to youngest, under circumstances of intimacy to be attained in no other way while covering such a space of time and extent of territory. The responsibility of the College to keep its vast family of sons in reasonable touch and in harmonious step can be best of all fulfilled by reaching that family through these delegates. The secretary is the one man of his class who is at the same time in close touch with the College and in close touch with his fellows. On him, in each case, the College is forced to rely, and does with entire confidence rely, for the carrying out of its responsibilities to the men he represents. To ask the College to carry them out by reaching all the individuals directly is impossible. It must act through foci of infection and thus permeate the whole lump. In a way the secretaries of the various classes are officers of instruction, unpaid and largely unthanked, whose task it is to interpret Dartmouth as she now is to those who knew her in older years; whose hope it should be to keep alive in every man within the class jurisdiction that flame of loyalty and pride without which our faith is vain. The responsibility of the College to its alumni is great, and the secretaries are its ministers.

It is my favorite theory that the alumni are as much a part of the College as are the president and fellows, the faculty and students now in residence at Hanover. All are but parts of one inclusive whole and the vital thing is to make them all function harmoniously together for the advancement of the College and the effective service of mankind. The responsibility of the College cannot extend to the point of compulsions. It is fulfilled by merely deserving the loyalty and the devotion which it asks and must have. It must not only "go on being a good college," but strive to make you, its graduates, know that it is such and make you glad and proud to be numbered of its goodly fellowship.

The College Yard

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT ARE THE TRUSTEES DOING?

June 1924 By Lewis Parkhurst '78 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleSaturday Morning Session

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES

June 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

June 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Article

ArticleERNEST FOX NICHOLS

June 1924 By Professor Gordon Ferrie Hull

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleSea-Anchor for Dartmouth

January 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWhy Pick on Friday?

January 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

June 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleCrime Does Not Pay

November 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleReligio Collegii

December 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe Fourth Estate

May 1946 By P. S. M.