ONE RESULT OF THE WAR has been a renewed manifestation of man's propensity, when facing any prodigious cataclysm which emphasizes his helplessness, to turn instinctively to God for aid. Deeply hidden as the innate impulses of what we usually call religion may come to be in times of normal peace and security, they are likely to come to the surface in periods of stress, even in the case of individuals outwardly obdurate and seemingly indifferent toward religious concerns. It has been remarked that "the undevout astronomer is mad," delving as he must in the stupendous mysteries of the well-ordered universe; but it is becoming apparent that the undevout soldier is also a rarity, despite rough language and a mouth full of strange oaths, after a brief experience in the man-made hell of war. It suffices to raise the suspicion that religion in mankind is not dead, but only sleeping. No doubt it is deplorable that consciousness of God is thus appealed to only in the face of overmastering dangers; but of the multitude in a rationalistic age it would seem to be true, and it may be questioned how long the reawakened religious impulse will endure once the stresses which revived it are withdrawn. The temptation is to dwell for a moment on what education can do about it, if it can do anything.

Compulsory chapel was abolished at Harvard, if memory serves, as long ago as 1886. It was given up at Dartmouth much more recently. One suspects that in both cases increasing numbers and the inadequacy of chapel space had much to do with the abolition—plus a growing belief that compulsory ministrations did but little to enhance genuine religious faith. Voluntary attendance has indeed remained possible, and the stress of war has unquestionably augmented the readiness of young men not yet in active service to interest themselves in religious matters. How about the future, when peace returns? Will readiness to seek the consolations of religion continue active enough to be reflected in voluntary attendance on formal religious services? For a time, no doubt, it will. How about the long run?

Perplexing as are the problems of education in other directions, they are nowhere more so than in the realm of interpreting God to man in terms which modern man can accept. What was religion yesterday may easily be superstition today. If the church has seemed to fail, it is chiefly in finding something to substitute for the sort of faith which came easily to the race in what one may call (with due reverence be it spoken) the Santa Claus stage of development. Too easily do we assume a conflict between science and religion, as if a more accurate knowledge of the immutable laws of nature must be meretricious if it differs from the ideas set forth in the childhood of human understanding. The received idea of what constituted religion varied comparatively little from the days of Eleazar Wheelock to the days of Samuel Colcord Bartlett, and the notion that any deviation from the simple narrative of Genesis must necessarily be an impious defiance of religion has died extremely hard. The idea that the laws of physics, chemistry, astronomy have been of God's devising from the day of creation, and are now only better comprehended, has been hard to implant. But must it necessarily imply abandonment of that underlying faith to which men turn impulsively under the stress of moral and physical shock?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE FOUNDING FAITH

December 1944 By EARL CRANSTON '16, PHILLIPS PROFESSOR OF RELIGION -

Article

ArticleTHE FIRST 175 YEARS

December 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

December 1944 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

December 1944 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S CHARTER

December 1944

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleGirding the Loins

December 1942 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleSacrifice Always Hurts

April 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleJust What Is "Practical"

April 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe Quiz Adolescents

June 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleCultural vs. Practical

April 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe Pity of It

February 1946 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

ArticleA. W. LAHEE ADDED TO TUCK SCHOOL FACULTY

January 1922 -

Article

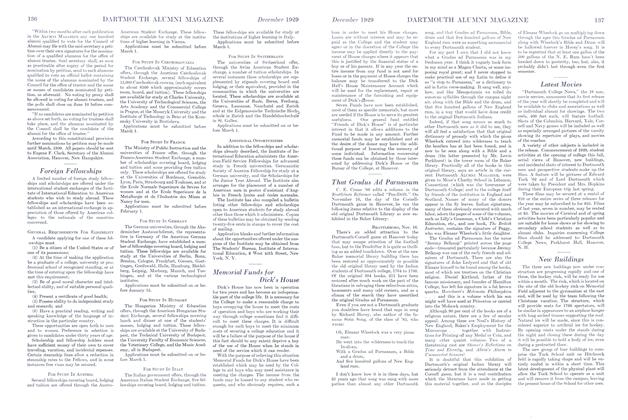

ArticleThat Gradus Ad Parnassum

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

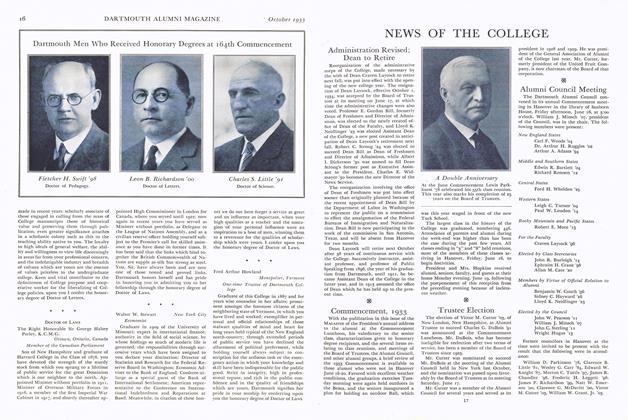

ArticleAlumni Council Meeting

October 1933 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1955 -

Article

ArticleAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2004 By Amy Dobrian '87 -

Article

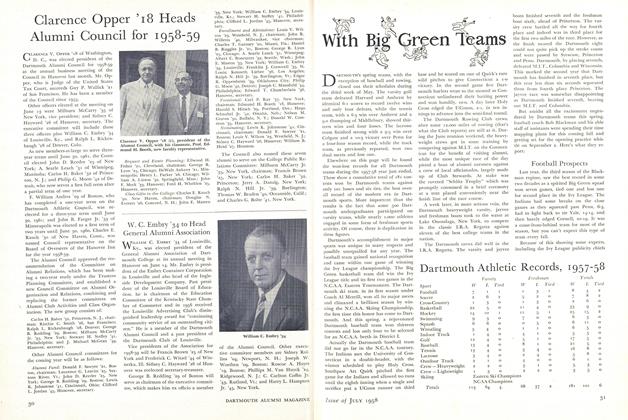

ArticleDartmouth Athletic Records, 1957-58

July 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45