the undergraduate contribution to the current survey of educational problems at Dartmouth, especially as embodied in the preliminary report of the student committee selected to consider this important problem, the more one is likely to be impressed by the evident thoughtfulness and sincerity with which the problem has been approached. We have quoted before, we believe, the admirable definition of the aims of a college, as set forth by this committee at the outset of it§ remarks; but it puts so much in' so small a compass and so well that we venture to reproduce it °nce more, with the remark that if the student committee did nothing else it would be justified by this one brief paragraph. The definition reads as follows: "It is the purpose of the college to provide a selected group of men with a comprehensive background of information about the world and its problems, and to stimulate them to develop their capacity for rational thinking, philosophic understanding, creative imagination and aesthetic sensitiveness, in order to inspire them to use these developed powers in becoming leaders in service and society."

Inasmuch as no small part of our perplexities has inhered in a vagueness of conception as to what the colleges were really after, this effort to crystallize their purpose in a brief and comprehensive statement seems to us extremely useful. There seems also to be but little ground to question its adequacy. It is, of course, only the bare statement of the problem and cannot be regarded as advancing its detailed solution beyond the point that at least it isolates and specifies the aims. When the undergraduate committee addresses itself to the task of suggesting the means whereby the aims are to be served and measurably attained, it is bound to be much less convincing and more surely open to dispute. Let us start, then, by commending the definition of the problem itself and by recognizing its essential importance. In a single sentence of some six lines of manuscript, the committee has devised a peculiarly satisfactory outline.

Neither can there be very serious dispute of the claim that the colleges should confine their efforts to the most promising material and should therefore "concern themselves with none but superior talent." A distinction is drawn in the report between common school education and college education—between secondary schools, attendance upon which is compulsory ; high schools, attendance upon which is encouraged for all young people —and colleges where attendance should be encouraged only in the case of such as evidently have the capacity and desire to profit thereby.

This is a frank recognition of the principle which President Hopkins has on more than one notable occasion presented for consideration. It amounts to a candid recognition of the fact that not every young person is fitted to profit by collegiate training and is a plea for an honest effort to restrict the raw material to that which is straight grained and suitable to be developed. This fact we believe deserves to be recognized without any effort to gloss it with delusive phrases. To many it may seem an unwelcome factbut if fact it be, which few will deny, it is not one to ignore. As we shall later point out, it may be the answer to the whole question.

The college should open its doors as widely as possible to young men and women who are intellectually alert and who have a genuine desire to avail themselves of what the college has to offer. Those who would come chiefly for the incidental pleasures, for the companionship, sports, social activities and so forth, rather than primarily for self-development by education, might profitably be excluded with a determined hand. No one of sense deplores the existence of those incidental pleasures. They are a most useful and necessary concomitant. But they must be recognized as concomitants only, and not as the chief thing for which colleges exist.

One may not wisely demand too much of young people at 18. It would be superlative folly to expect of young men and women at the age for entering college that sober earnestness of purpose which one might expect at three score. We take it that no such theory is involved in the plea for making college training a matter for "a selected group." One asks only the reasonable amount of recognition on the part of youth for the larger aspects of a college education—a realization that this college life is not a sort of gay adventure which it is fashionable to undertake, but is after all a rather serious thing, with a definite purpose in the scheme of life which is its sole excuse for being. One incapable of treating it as such would better remain away, since his presence is a handicap and deterrent. To subordinate education to the concomitants is notoriously common. To regard studies as bugbears impairing an otherwise ideal existence is all too easy when one is at that age. Who of us, mindful of his student days, can deny it or be greatly perturbed over it ? And yet, our colleges have grown of late to such unwieldy proportions that the time has come for a greater insistence on keeping the student body down to limits which can be handled without undue waste and with discernible benefits.

All of which, while useful, is but a preliminary. It outlines the purpose of the college and specifies the sort of people who should go to college with that purpose consciously in view. It leaves us puzzled and perplexed as to the specific means by which these selected young persons are to be "provided with information about the world," inspired with "philosophic understanding, creative imagination, aesthetic sensitiveness," and trained to a habit of sound thinking. So far as we have gone, we may without very much hesitation accept the view set forth by the undergraduate committee. When it comes to appraising their idea of an ideal curriculum designed to carry out the aim professed, one may be pardoned for hesitating long.

Fuji credit should be given at the outset for an obvious honesty of purpose and manifest anxiety to suggest appropriate ways and means. The intrinsic wisdom of the suggestions, concretely considered, is what affords the ground for debate. These young men have set forth what seems to them a good general scheme for the four-year courses leading to the A.B. and B.S. degrees and evidently believe that it would better serve the avowed aim of the college than what exists now. They may be right. They may be wrong. Most probably they are right in part and wrong in part. At all events they have filed their brief—if a monograph of some 40,000 words may be so described—and have done it uncommonly well. It seems to us a distinct contribution to a problem which has bothered older and even wiser heads.

For a guess, the older and wiser heads will measurably agree with the undergraduates in the postulate that the courses in the first two years, whatever they are, should be mainly required, and those in the last two years mainly elective. That doctrine is not new and it has much to commend it. The differences will arise mainly in considering what subjects ought to be required. Whether Latin, for instance, should be exacted of the aspirant for an A.8., and mathematics only of the seeker for a B.S. degree, may well be doubtful. Yet we gather from the preliminary report before us that the undergraduate suggestion contemplates some such thing. It specifies for freshman year a course common to both degrees, in that it would require English literature and composition; historical backgrounds of contemporary civilization; a course on the general nature of the world; a modern language; the technic of thinking; but would demand Latin without mathematics of the A.B. candidate, and mathematics without Latin of the B.S. candidate. Quaere de hoc.

For sophomore year there is suggested a course in present-day problems; a course in literature; a course in science; problems in philosophy or art (one or the other to be taken in junior year, as desired) ; and one elective course.

In senior year and junior year alike, only 12 hours a week are suggested, from six to nine of those hours being at the disposal of the department in which the student has decided to "major" and the remainder freely elective.

Now in such matters the layman long out of touch with college and academic jargon is out of his depth and his opinions are worth little. There is room for the suggestion, However, that perhaps the debaters of such problem are being unduly impressed by the special worth of some studies over others as the special agents of development. "Mental discipline" has always seemed to us to be promoted about equally by sciences and classics. We have even a doubt whether the college of our fathers' day, which was predominantly a classical day, failed to stimulate a capacity for rational thinking, or was at all deficient in its inspiration toward philosophical understanding, creative imagination and aesthetic sensitiveness. In fine, after we have mulled this matter over to our hearts' content and have devised a novel scheme of things in which a different set of agents is to be employed, we doubt that the net result is going to differ much from what it was. We even doubt that it greatly needs to differ. Much more seems to us to depend on getting the right sort of young people into the colleges than on the particular subjects they study while they are there. This may be heresy—but we can no otherwise.

The conclusion of the whole matter, as it now presents itself to us, is that when the undergraduate committee set forth that admirable definition of what the college was for it did its most important work and came very close to making further discussion needless. It was closest of all to the main stem of the whole problem when it intimated that the colleges should spend their time and effort only on such as could reasonably profit by four years of contact with a highly intellectual and cultured environment. After all, does it matter much what special things one studies given the desire to develop a reasonably alert and retentive young mind? The realm of knowledge is so vast that no one can traverse it all in a lifetime, let alone four years. The notion that one should "know a little about everything and everything about something" is a questionable one, from the practical point of view.

It may sound like cynical conservatism to say that there is less trouble with the educational machinery than, with the raw material fed into it, and like oldfogeyism to insist that young men were quite as well educated 60 years ago as they would be under a revised curriculum representing the modern students' ideal. But there must be many who feel that these things are so, and that in our experiments, shifting from sciences to classics, from electives to requirements, from recitations to lectures, and back again, we are dealing with very secondary matters and are affecting the underlying premises very little if at all.

With Commencement closed the one hundred and fifty-fifth year of the annals of the College—a year marked by all the evidences of healthy growth and by material expansions designed to keep pace therewith. It is agreeable to record that all indications point to a sustained activity, that the selective process for is .operating encouragingly to promote the highest excellence of the student bodies of the future; that the enthusiastic support of the alumni continues; and that the general situation is one which should enhance, if that be possible, the great pride which the graduates of Dartmouth take in the remarkable development of the institution to a place among the greater colleges of the country. The past at least is secure, and the future is as promising as could well be asked.

It is the desire of the MAGAZINE in what follows to stress only the points of primary importance to the alumni body. First and foremost it seems proper to bring to the mind of every reader, and make a part of his collegiate consciousness, the principle of noblesse oblige. This new Dartmouth which we praise so, this new Dartmouth which fills us with such satisfaction and pride, brings with it a distinct obligation which we have to acknowledge and confess as members of its fellowship. The College has no endowment to yield the funds absolutely necessary to supplement what is paid by those in process of education; and it is imperative, this year and every year, to make up the discrepancy between income and expense by means of the Alumni Fund. To this it is desirable that every individual alumnus contribute whatever it is reasonably possible for him to contribute; and in order to make this operation as painless and as little burdensome as possible, a hearty willingness to make this a recognized part of one's personal budget is urged. It ought not to be a thing which must every year be argued, pleaded for, campaigned to success by main strength and effort, under the direction of an increasingly elaborate organization. It can never be entirely automatic, of course, but the wear and tear on organizers and class agents can be curtailed to a minimum by intelligent and cordial cooperation.

The great growth of the college gratifies us all. We all want to hold it. We all hope to see it made permanent, if not further increased. But if we are to make it permanent, we have only the choice between making it hard and making it easy to raise this annual fund. Is it too much to ask that every alumnus of Dartmouth College face this thing and decide to make it as easy as possible by meeting the annual necessity half waymore than half way? This duty cannot be escaped, save by forfeiting all that we have struggled up to and lapsing back into a condition which would be harder to tolerate than ever before because we have tasted the better things.

Those of us who, by reason of circumstances, are closer to this proposition than others, have known the difficulties best. It was reported at the Alumni Council meeting in June that an appreciable progress was being made toward educating the alumni to regard this fund as a definite, regular, annual and personal responsibility. Nevertheless the steady growth of the College, the annually larger number of alumni, and the necessity ot meeting a budget which tends to increase proportionately to the size and scope of our institution, tempts the Fund organization more and more into the easily besetting defect of all such affairs—to wit, that of over-elaborate organization and an excessive overhead expense. The editors of this MAGAZINE must regard it as very injudicious to add to the overhead cost of collecting this money if that can be avoided. Recently the cost has been approximately six per cent. That is, it has been necessary to spend six cents in order to get every dollar. That is high—too high—but it is so only because we, the alumni of the College, have to be appealed to so extensively and so often before we are brought, to the pitch of giving our appropriate share.

It is not a pleasure to be forever harping on the monetary string, but in present circumstances it seems to us the first and great commandment. The Alumni Fund is the key to Dartmouth's whole future. It affords the answer to the question whether we are to go back or to go forward. If we want to make the glorious great college that we now have into an enduring and even more glorious permanency, we have a price to pay, each one of us, down to the last man. It is not a staggering price—certainly not if each helps as he honestly should. It is well worth paying. It has been paid for this year, but there is a year to come. It is therefore urged that you, the reader of these lines, plan now to give next year whatever it is just that you give, and give it with a cheer—at the very first appeal of your class agent.

One momentous thing done at Commencement was the adoption by the General Association of the Alumni of a report by a special committee on revising the system of choosing alumni trustees. To boil this proposition down to its essentials, the trustees -of the future, who may sit on the part of alumni representation, will be chosen by the Alumni Council alone—save in the very rare case, if such ever does arise, where 100 alumni by petition insist on the nomination of a further candidate for the vacant post. That is to say, in normal conditions every such vacancy will be filled by the unaided Council, to which body the alumni have voted to delegate the entire responsibility, without asking for the subsequent ratification of a general plebiscite.

This solution we unhesitatingly endorse. The Council is, in effect, the executive arm of the whole alumni body. It is a sort of replica in miniature of the whole alumni body. It does what the alumni must do, but could not do effectively if all had to act. It is apparent that with 6000 widely scattered graduates anything resembling direct government, or anything savoring of a town meeting, is utterly out of the question. It is inevitable that resort be had to a representative body of workable size, which can actually meet around a table and talk things out. Hence the selection of alumni trustees has for some years become a function of this miniature cross-section of the alumni; but until now it has been necessary to have the choice ratified by a general ballot, which meant nothing and merely imposed an irritating burden by asking all hands to vote on a single nominee who was already as good as elected. That has been abandoned, and wisely. It is proposed by the same committee to remodel somewhat the system of electing the members of the Council, so as to make that body more democratically representative of the various sections into which the country is divided.

In fine, the report has abandoned altogether the attempt to democratize the system of electing trustees, but seeks rather to democratize the election of the councillors who are to elect the trustees. Having done this, it is felt that the delegated body may wisely be trusted to function for the whole alumni association without further oversight. In an extreme case, however, there is provision for the making of nominations by general petition, provided 100 alumni can be mustered to sign such. Failing that (and it is difficult to believe that resort would ever be had to it save in most extraordinary circumstances) a representative Council will hereafter canvass the field and choose out of it such trustees as seem to that Council best qualified to serve, in the name and on behalf of all the alumni.

The remodelling of the Council to enhance the democracy of its membership was legally impossible at the June meeting and was therefore put over until next year. No more than a technical difficulty exists, however, and the practical working of the system is therefore not delayed. Meantime the real effect is to perpetuate the very serviceable system which we have had all the time—merely lopping off the meaningless referendum which without beneficial result has been bothering the entire body of the alumni.

The above must, as we see it, tend to make more clear to the graduates in general the increasingly important place which the Alumni Council is destined to fill. The Council is in fact "the Alumni in Council Assembled," just as the legislature of a state is the "People in Legislature Assembled." It is the outgrowth of a political necessity, precisely as the institutions of any representative government are.

There is in use, we believe, a device in military circles known as the "subtarget gun, which amounts to a diminutive &un capable of being operated in such wise as to demonstrate exactly in a laboratory, what a full-sized weapon would do in the open. The Council is designed to function in somewhat the same way. It is a scaled-down alumni association, carefully devised to reproduce the entire body by representation and capable of getting together at need to do the things which it would be absolutely hopeless to ask the alumni to perform in the mass. The suggestion that we should look more carefully to the composition of this subsidiary body is pertinent and wise.

It is the only point in which an increase of democracy is possible and to that end a system of choice has been outlined which will be taken up in more detail as the time for acting on it approaches. Otherwise the composition of the Council remains the same—i. e., in numbers and in assignment. The one improvement sought is to insure the accuracy of district representation through the votes of the dwellers in each district.

Alumni present at Commencement and listening to the orations of clever young men who had attained Commencement rank, may have speculated whether the wise views elaborated there represented the general view of their classmates, or were merely the outgivings of individuals who, by their unusual scholastic attainments, might be denominated "intelligentsia." To one greatly perturbed by the so-called "Liberal" activities of the day, it might even seem that these well-assured young gentlemen, with their little reverence for the established theories and their evident immunity to self-distrust, denoted rather more potency in the "radical" virus than the reassurances of those in authority had implied. It is probable that some uneasiness of mind was felt in a variety of such assemblages everywhere at hearing eloquent seniors extolling the spirit of revolt from numerous college platforms, or on discovering that unction was being laid to the senior soul because a packed house had greeted some obnoxious pacifist lecturer, whose sole claim to notoriety rested on his having been under duress during the war for his conscientious scruples against serving his country like other men.

The true answer, one suspects, is that "intelligentsia" remain the same breed, whether old or young. It may even be fortunate that the average country is ruled by its ignorantsia! Meantime there awaits a rising vote of thanks, in about every college audience in the world, for the humble young man who will some day arise and confess that he has no panacea for curing all human ills; who will admit some virtue in established order; who will disclaim any personal expectation of ushering in a new heaven and a new earth; and who will assert that while he does not know everything he is willing to be taught. This may some day happen. The more customary thing, however, today as in former days, is for the Commencement orator to inform the older generation as to the precise point where it gets off, accompanied by specifications as to where the new generation gets on and assumes the steering-wheel. In view of the fact that the younger generation is now, and always has been, rather invited to feel its oats than to be seen and not heard, it is difficult to blame it. More of that seems to be going on now than in older days—but it has always been more or less true.

It might be hazardous to say which was more open to criticism—the cocksure young man on the platform, outlining his millennial program with such ill concealed disdain of his elders; or the intolerant old graybeard below, who listens with a pitying smile to what he must unhesitatingly denominate boyish twaddle. For both are wrong. Out of the glowing hopes of graduating seniors comes much that is foolish and a little that is wise. Out of the hardened cynicism of the old graduate comes much that is wise and a little that is foolish. The young have some excuse for their folly. What extenuation for those of us who boast from thirty to fifty years of experience with the world since we made our Comnencement orations?

It is claimed that no real harm, but rather much good, flows from these immature young Liberals whose delight is in purveying every year a list of lecturers from outside, in which a certain rapscallion element usually lends pungency and pep. That may be so. We suspect it is at least better to let the Liberal have his fling than to tell him he shall not. But it might be wise to insist a little more urgently than we seem to do on the distinction—it is a very real one —between liberty of thought and anarchy of thought. Meantime it is well to remember that an "intellectual," whether in boyhood or later, is bound to reveal the infirmities of the breed; and that the cult is known to excel in no popular indoor sport save that of hurling the self-addressed bouquet.

The world has been undergoing reform at the hands of college graduates for ever so long—and as a matter of fact it is commonly believed to be a somewhat better world than it was before, taking it by and large, despite sporadic and possibly symptomatic slumps. But the Commencement speech one makes at 22 is apt at be a very different one from the Commencement speech the same man makes when he stands up at the alumni dinner to respond for the class at its 50th reunion!

The leading student organizations of several colleges in New England and elsewhere appear to have coincided of late in a movement to urge on the part of alumni a genuine cooperation in discouraging the abuse of liquor in connection with college functions—whether at home or away. It is apparently the universal experience that a few alumni, by thoughtlessness rather than anything worse, often contribute to make it difficult to enforce among the students themselves that regard for law and college regulation which it is mainfestly important to enforce; and this has led more than one institution to make a concrete appeal to its alumni to avoid complicating a situation sure to be quite complicated enough at best. It has been phrased as an appeal to the alumni to "behave at least? as well as the students."

This, no doubt, should not be necessary; but it would be an insult to the intelligence of any observant person either to maintain that it is entirely without its ground of justification, or to assert that any one college more than any other is either especially subject to this necessity, or especially free from it. The situation is as nearly universal as can well be imagined; and we honestly think it is time for the whole fraternity of college graduates, regardless of locality, to unite in an honest effort to promote a more healthy public opinion with respect to this matter.

The natural hesitancy of many to be candid, through fear that their candor will be misconstrued as implying some special sinning in their own college, seems to us a mistake. The fact is that all the colleges are very much alike in this regard and require practically the same urgence for their betterment. The proof is that so many independent appeals for alumni cooperation sprang into being last June at the Commencement season, all over the country, without prearrangement of any sort. Alumni coming back to a reunion and being desirous of observing ancient traditions may easily be too thoughtless of the effect on younger men, and on occasion may even be unduly liberal in sharing their supplies. It is against this that the students themselves have been moved to protest, in a number of American colleges. It is worth the attention of the alumni in all colleges.

This is not a question of one's abstract belief or disbelief in the present form of American prohibition, but one of perfectly concrete right and Wrong. Moreover it is clearly a matter which is to be dealt with only by force of public opinion. Individuals cannot be coerced by rule in any such case. The alumnus who chooses to supply himself with satisfactions which the law denies will certainly do so, and no one can very well prevent him. But it should at least be possible for such to heed the growing desire that this be kept a purely personal gratification and that it be not abused in such ways as to impose temptations on others, or to reflect discredit upon any college gathering, whether on the campus or in remoter places, where the name of a college is prominently and officially involved. Transgressions of this kind we have all seen, probably—at reunions, at college games, at class or college banquets in cities far away. The hope is that they will come to be numbered among the things that "aren't done."

We have the idea that Dartmouth at present suffers much less than do some others from this particular menace; but we are ribt so foolish as to ignore the general desirability of keeping it down, and we are not so squeamish as to wish to do any pussyfooting, or to countenance any hypocrisy with respect to the whole situation. It isn't a thing for any single college to deal with, but for all to unite in combatting. And the first essential may well be to outgrow false dreads of individual misconstruction, in the hope of promoting the common good.

In the death last May of George L. Kibbee of Manchester, the College has lost an old and valued friend. Mr. Kibbee was not an alumnus of Dartmouth but by virtue of the honorary Master's degree awarded him in 1922 had become a member of our fellowship; and thus was brought into direct contact with the College a man who for many years had shown a great and helpful interest in its growth and prosperity. Mr. Kibbee had all his life been a newspaper worker in the city of Manchester, the latter years being especially fruitful through his services as the chief editorial writer of the Manchester Union. To this exacting duty he brought a rare gift of expression and the essential qualities of personal honesty and shrewdness of perception, qualities which made the Union's editorial page to be widely read and universally respected. In a state constituted as New Hampshire is, with few large centres of population but with numerous scattered towns, it is usual for a newspaper of the most considerable city to serve as a sort of mentor for all sections of the commonwealth. This, under Mr. Kibbee's editorship, was peculiarly true in the case of the Manchester Union, the worth and sterling judgment of the man commending themselves to a steadily increasing army of readers. Dartmouth had especial occasion to appreciate Mr. Kibbee's kindly interest and his faculty for sympathetic interpretation as applied to the incidents in which the College called for editorial comment and editorial criticism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMENCEMENT 1924

August 1924 -

Article

ArticleRECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES

August 1924 -

Article

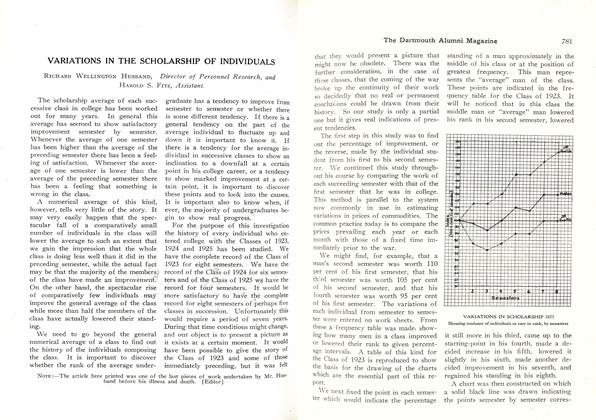

ArticleVARIATIONS IN THE SCHOLARSHIP OF INDIVIDUALS

August 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

August 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

August 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1924

Article

-

Article

ArticleELECTION RESULTS IN HANOVER

December 1916 -

Article

ArticleKissinger to Speak at Rockefeller Center Dedication

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

June 1987 -

Article

ArticleDean Tribus Comments—

JUNE 1964 By —MYRON TRIBUS -

Article

ArticleClass of 1985

Mar/Apr 2007 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

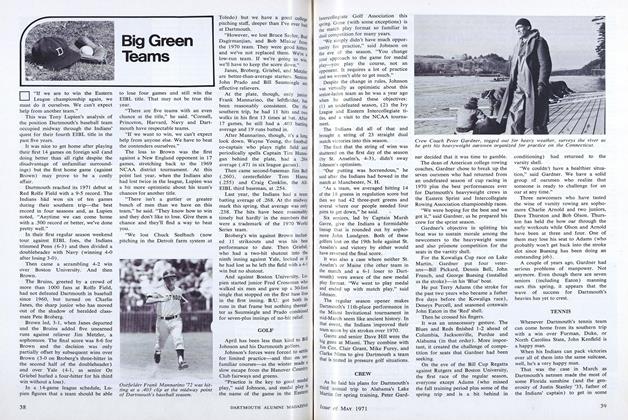

ArticleTENNIS

MAY 1971 By JACK DEGANGE