There are several reasons, I suppose, why a Journal is intriguing,—one is that we all are predisposed to curiosity if not interest in other folks' affairs; another is, that all of us are sufficiently optimistic to be perennially expectant that someone of the writers of memoirs will be as frank as they all say they are going to be; and there is the further lure that a Journal gives us a life in high relief with its significant events accented, for it is as though the movie people should each day during a long life take a photograph of an idividual identically placed, and at the end of many years exhibit to us infancy growing into youth, youth ripening into maturity, maturity withering into doddering age,— all in five minutes.

So we read with mild anticipation the preface to the holographic Autobiography of Ralph Butterfield*: For sometime past my health has been bad and I have often thought it might prove interesting to some of my friends (in case I should be called away from this world of sorrows) for me to leave some memorial of my somewhat eventful career.

I have thus been led to commence this my Autobiography and I shall endeavor to write the truth so far as I can dis- cover it. If it can prove a source of any amusement or interest to my friends to review the history of my life the object I desire will have been attained. "Go, little book, from this my solitude! I cast thee on the Waters, go thy Ways; And, if, as I believe, thy Vein be good, The World will find thee after many days." Rifle Point, La., Dec. 27, 1850.

If there should arise those who criticise the fulsomeness of the above, please let them remember that it was written at a time when American artistic taste was not very good, when such lines as, "If scribbling in Albums the Mem'ry insures, etc." were considered literary, and when the most absorbing; occupation was polishing up the squirrel rifle in preparation for the coming Civil War,—sad commentary on human nature that bigger game than squirrels must occasionally be shot!

The system followed by Doctor Butterfield was unusual. When thirty two years of age, he, having lost his four most intimate friends and not feeling very well himself, wrote his Autobiography, a sort of set piece or, as the country correspondent would say, a floral tribute, handed to himself while still alive. Then, as each of the succeeding forty two years of his life rolled around, he added, in a manner of startled surprise at having been spared another year, a postscript, or small bouquet, bringing his life up to date.

Ralph Butterfield was bom in Chelmsford (now Lowell), Massachusetts, in 1818. His father died while Ralph was a child. The boy, whose mother was left in straitened financial circumstances, lived a little while with his mother, and afterwards with various relatives in and around Lowell. He attended district schools and several preparatory schools; one of the latter was Phillips (Andover) Academy, from which he separated in the following manner:

During this time an old gentleman was the Principal, but he soon left and his place was filled by another. Of this man I shall express my sentiments freely, he is now in his grave, having finished his course, and some might think I ought to forget any injustice he may have done me, but I cannot and never shall. He was one whom I utterly despised. How little calculated was such a man for the management of boys like myself ! He had no sympathies in common with them; he had no kind words or advice in a friendly way for a wild youth when he sometimes wandered from the strict paths marked out for him.

But I may as well record the principal act of injustice he did me. He seemed to have an antipathy to me and a few others and would embrace every occasion to find fault with our conduct and chide us in the most contemptible manner. I do not now recollect of his having reprimanded me more than once or twice; but his great object and aim wa,s for us to become religious, as it was termed, and revival after revival passed without drawing us into "the fold." This was a mortal offense with him, as I have heard him say that "it was better that' the ungodly should not be educated, as their opportunities for doing harm in the world were increased by a liberal education."

True to his theory, he determined to stop those from school who would not yield to his "pious" instructions. I had gone home and spent the summer vacation with my friends in Lowell as usual, and after it was past I returned to Andover with the expectation of continuing my studies. On the evening previous to the opening of the Fall term, he sent for me and informed me that he had written me a letter during the vacation saying he did not wish me to return to his school.

I was surprised at such a communication from him, and I wished to know why I could not enjoy the benefits of the Academy; he could give no reason except that he thought my influence was deleterious to its interests.

I went to my friends and carried a letter from the principal, but it gave no good excuse for his sending me home; they thought that I must have done something very bad, and though I assured them that I had not, it did not satisfy them and so my uncle took me along with him and went down to Andover to see the principal. Nothing could be elicited in extenuation of his conduct towards me except that my influence was bad. My guardian was sure now that I had committed no very heinous offense and he never seemed to blame me in the matter.

Young Butterfield next attended Lowell High School, at which one of his companions was (General) Benjamin F. Butler. He had little, if any, better luck at that school, for while attending it a bolt mysteriously disappeared from an outer door and he was suspected of having taken it; he told the Principal, Mr. Merrill, that he didn't take it, but admitted that he knew who did and refused to tell. He was expelled.

My word was pledged and I have ever considered it sacred and have tried to keep it so. Suffice it to say that the pedagogue Merrill, enraged at my independent way of talking to him, used his influence with "the powers that were" and I was dropped from off the books of the High School.

Dropping, as above described, from off the books of the High School, he landed in Pinkerton Academy, Derry, New Hampshire, where he completed his preparation for College, under the supervision of Mr. Abel F. Hildreth, whose considerate understanding of boys quite won the heart of this boy from Lowell.

Even while under Mr. Hildreth he narrowly escaped scholastic disaster, for with a companion he remained all night at a Camp Meeting and had to be reproved therefor, but the reproval was a mild one, the boys were penitent, and the incident passed without serious results. Perhaps Mr. Hildreth took a certain pride in being able to keep in his school the orphan lad whose spirit repeated revival at Phillips Academy could not break, and who was expelled from Lowell High School for refusing to reveal the name of the boy who took the bolt from an outer door !

He entered Dartmouth College in August, 1835, being led to the decision to enter that particular college partly by the fact that expenses there were less than at Harvard and Yale, and partly because several of his schoolfellows were going there. His Class when it entered numbered sixty-three, the largest up to that time that had ever entered Dartmouth.

We were a motley crowd; most of us were strangers, though there were a few whom I had met at the schools at which I had previously been. Some were men of from 24 to 26 years of age and one or two even older, some few were boys of 14 or 15, but the most were from 16 to 20. My age was 17. Some were sobersided, long-faced, "pious" young men; some again were merely "steady," "moral" fellows; and a few were what were considered by the two classes I have just mentioned as the "wild devils."

During the first term I formed no very intimate friendships, but of course I soon discovered whom I liked and disliked of our number. I was rather inclined to associate most with those who seemed to be a little inclined to enjoy themselves without committing any very great breach of the College laws. I was invited to a few "suppers," the turkeys and some of the other ''doings" of which had been "hooked" and prepared within the College walls. This, to be sure, was not exactly in accordance with the laws, but no one interrupted us, though I have no doubt that the tutor who had a room near us must have smelt turkey, for it took a long time to roast it and then we did not get it quite done before our appetites got the better of our patience and we fell to. But I can say I never ate a poorer supper but once, and that was made of an old hen which a classmate and I hooked and cooked, or thought we had cooked, but on trying it, after having sat up nearly all night, we found our dentistry quite unequal to the task..

The Faculty at Dartmouth permit the students to remain away during about three months in the winter for the purpose of teaching school. I embraced the favor and obtained a situation in Felham, New Hampshire. I got through with my school and glad enough was I, for it was a tedious business to me to drill the country urchins in the rudiments of the arts and sciences. School teaching is a business very much followed by New England's sons but they mostly make it a stepping stone to some more lucrative and pleasant occupation or profession.

The Freshman year having passed, I was pleased to find myself a Sophomore, and now we were getting more acquainted' and friendly we, that is I and my companions, managed so as to get rooms in the same house and we occasionally made some noise at night. The President took occasion to have us up and gave us a little good advice as to the noise, etc.

Towards the end of the first term the store of T. Man, commonly called "Typy" from his being a printer, was most woefully bedaubed with black paint. Inquiries were made to find out who were the authors of the mischief; several of our Class were called up and nothing could be discovered. The real authors were a friend and classmate by the name of James C. Billings and the one who now pens these lines. We were not suspected; a club of students had a meeting on the night the house was bedaubed and as it was a halfconvivial, half-literary club suspicion fell on some of the members bf the club. Billings and myself had withdrawn a short time previous and so avoided suspicion. The term was near its close and the investigations ceased and we escaped though we were very much afraid we should be detected.

Doctor Butterfield's particular friends while at College were Walter H. Tenney of Dunbarton, New Hampshire, Warren A. Giles of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, James A. E. Mferrill of Pittsfield, New Plampshire, and James C. Billings of Sharon, Vermont.

The sophomore year passed away very pleasantly; having formed and kept up our acquaintance now for a sufficient length of time to trust one another we enjoyed ourselves very much. I was now more careful about my lessons and made out to pass along so as to escape another vacation's study. I also managed to keep well out of scrapes, for I had come pretty near detection once (in painting the house) and whatever I did was well planned and I was regarded by the Faculty, I expect, as a very moral young man,—at any rate I was not called upon to answer for any misconduct.

Junior year came. We were half through College and now our severer studies were over and we could pass along without much trouble as regards them. I had my room in an old building, the Tontine, then in a neglected condition mostly, but now repaired and owned, I believe, by Prof. Young and Mr. dell, both gentlemen connected with the College, the former a Professor of Mathematics, the latter as Treasurer. My friend Billings had his room near me and in the same building part of the year. My room was a frequent place of resort for my friends, being away from the College and not so much under the supervision of tutors, etc.; we could enjoy a quiet game of whist, or any other amusement, and were never disturbed by the College authorities. Once, 'tis true, a professor did open my door without knocking, but he shut it again very soon when he heard my exclamation. It occurred in this way:

Prof. Young had several carpenters at work through the building and was frequently with them. One day Billings and I were sitting before the fire with our feet upon the grate and a "principe" in each of our mouths, when, on glancing out of the window, I saw Frank Mussey, one of our Class and a frequent visitor of mine, approaching the Tontine and coming, as I supposed to my room. Just as time enough had elapsed for Frank to have reached my room, my door opened without the usual signal of a knock. Not looking around to see who it was, so confident was I that it was Mussey, I said in a loud and harsh voice, " you, why do you come in without knocking?" ' As I now cast a glance towards the door I saw Professor Ira Young standing there and bowing! He at once made the explanation that he "thought the carpenters were at work there," and retired before I had time to say a word.

Billings and I jumped up and grasped hands and laughed till our sides ached at the joke. It soon went to my companions, and I expect Young also told it, but I give him credit now and say it was never brought up before the Faculty, to my knowledge, as I had some fears that it might be. I have heard of this professor having seen students playing cards, and that he would not inform on them; this is more than can be said of most professors at New England Colleges.

During this year I visited the neighbor- ing towns and villages frequently. Leb- anon, 6 miles distant, was a very agree- able place of resort, the there being provided with everything in the way of amusement for jolly students. The President had occasion to call me up about going out of town so frequently and without leave, for which latter offense one dollar per term was generally added to my bill, which, I suppose, pleased the Treasurer more than if 1 had asked permission.

One excursion to Sharon, Vermont I shall never forget, and I will record it. On the farm of a man by the name of Ball in the town already mentioned was discovered a deposit of crystals of quartz, some of which were of singular beauty and richness as mineralogical specimens. The sons of Ball would frequently bring them to the College and sell them to the students, and we had made an excursion to the place but were not permitted to_ dig for the crystals as the Balls had conceived they would make a deal of money by selling them. This did not please some of us and a proposition was made by some of "our set" to go at night and help ourselves. I never for a moment thought we should meet with much success, the crystals being imbedded in the soil some foot or two beneath the surface, and were mixed with fragments of quartz so that the labor was considerable even in the daytime, but at night, when we should be obliged to work entirely by lamplight, it was even greater. My companions seemed to think differently and I was persuaded to join them in the piratical expedition.

Accordingly Billings, Giles, Merrill, Tenney and myself started in two buggywagons for the farm of old Ball, some nine of ten miles distant. We were provided with lanterns, hoes, spades, segars, provisions, &c., &c. We left Hanover just after dark, proceeded to cross the Connecticut River about a mile from the College when we were met by some of the President's sons and we were fearful that it would get to old Prex s ears that we were off on a spree, and so it did as will be seen shortly. _ We cracked our whips, however, and lighting our segars on we went through the pleasant town of Norwich, Vermont, and thence on to our place of destination, where we arrived safely at the hour of 10 P. M. Old Ball was in bed and so were all the family I suppose, for no lights were to be seen as we drove carefully by the house to the place where the objects of our search were to be found.

Having tied our horses, we went to the locality of the crystals and began to dig by the light of our lamps, but with very little success. The wind commenced blowing pretty hard and it was very dark and cloudy. We soon discovered that we could find but few specimens worth anything and so gave up and went to our carriages and started back, after taking a drink. As we passed Ball's house we gave a yell that made him and his family start from their slumbers, I do not doubt. We drove on for two or three miles when the buggy, which was before, suddenly stopped. Some part of the harness had broken and it was found on examination to be so badly broken that we could not mend it.

The only thing we could do in this case was to tie one buggy to the other and one was to ride the horse whose harness had broken. This was done; I took the reins and tried to start our horse, but having an additional load, and it being up hill, he would not go but commenced backing. I told Billings to take him by the bridle and thus try to lead him on, but it was no go. He continued to back, when I jumped out and gave him a cut with the whip but this made him worse,—he jumped backwards and down went horse, buggies, and all to the bottom of a hill against a stone wall. Soon the horse fell, the stones tumbling gainst him. Here was trouble! We could not get the harness loose and I thought the horse would kill himself, so much did he kick and struggle. Seeing that I could do nothing I got on the other horse and went back to a house nearby, hallooed at the top of my voice but I could not make anyone hear me, and I now think the house was uninhabited. This being the case, I returned to the scene of our misfortunes.

While I had been absent, the rest had been at work and with cutting and unbuckling the harness they had succeeded in getting the horse up. He was considerably bruised and injured, so much so that we did not deem it proper to try to make him work any more, being pleased to find that he was alive. So we put the other horse in one buggy and made all fast, after working several hours and being terribly frightened. This time we were successful in making the horse draw both buggies* but the load was too great for him to draw them and us too, so we drove slowly, one at a time riding and driving, while one rode the backing horse and the others walked. It had now commenced raining, the road was sloppy and we were tired, but we had to proceed as we were fearful that we should not reach Hanover in time to attend morning prayers, which if we failed to do we were certain to be detected as we should have to come into town by daylight, and our caravan would have excited attention on all sides. As good luck would have it we got home just as day was breaking and the Cocks were crowing.

A pretty set of fellows we were and I remember to this day that we laughed to ourselves when we looked on the strange appearance we made as day dawned upon us. Dirty, tired, and almost exhausted as I was, I went to prayers, but whether I heard them or not I cannot say, but I presume I was nearer asleep than awake. Nothing was said about our excursion for some days, but we were fearful lest the Faculty should get hold of it and so they did. Tenney and Giles were called up as being two of the party. Giles was always bold and frank,—he scorned a falsehood and could not be induced to tell one even to save himself; when asked about it he came out and told the President what was the object of the excursion, but I believe he did not tell of all the trouble we had with our horses and buggies. The President thought we had been on a frolick, but on Giles telling him the truth, he dropped the matter.

The year passed very pleasantly. I taught school at Westford, Massachusetts in the Winter, making some money thereby. At last the year was gone and, how quickly time flies when it is spent with agreeable companions! We were Seniors, feeling the dignity of the title as much as any set ever did, and we maintained it towards those below us to its fullest extent. We scarcely noticed the members of the lower classes, with a few exceptions. Some few of the class next below us we did deign to recognize, for they were good fellows and sons of distinguished men, or had something to recommend them to our notice. Our studies this year were less serious than any previous one so that we had little to do but enjoy ourselves. We might, 'tis true, have employed our time on our lessons and in reading and writing, but as former years had been passed in comparative idleness, so especially was this one.

During the last term an event occurred which nearly deprived some of us of our diplomas. It so happened that a Revival of Religion had been gotten up in the College and several of our Class had been drawn into it, but none of my immediate friends were of the number. One pleasant, moonlit night a few of us met back of the College and were "making night hideous" by the sound of any instrument which could be procured in the College. The windows were open and the students of the lower classes were cheering us so that we went on for some time with our music. I had a small French horn, Giles had a "conch shell," Tenney had a flute and Billings the same, Merrill had part of a clarionette. We were in high glee when suddenly the President appeared in our midst,—like deers we jumped and ran, but Billings was too slow to recognize the Prex, whereupon he put his hand upon his shoulder and said, "I have you Billings, who were the others with you?" B. did not like to tell, but as he was threatened with expulsion if he did not do so, our names were given with the exception of Merrill's which poor B. had forgotten.

The next day at one o'clock we were summoned to appear before the President at his study. Our hearts palpitated, at least mine did, as we slowly wended our way to the presence of the President. When we were all seated he began to reprove us pretty severely and we sat in silence for some time and let him go on till he said something which we could not well bear and then Giles, as on former occasions, became the chief speaker. The President had accused us of trying to raise a noise so as to interrupt the Revival. Giles stated boldly that we had no such intention; to this we all gave our assertions that by mere accident alone we had assembled and were serenading. President Lord found he had gone a little too far and had drawn on his imagination somewhat too freely, and so dismissed the subject by saying that if we were caught in any more scrapes before Commencement we should not have our diplomas. This was a serious threat and so we kept pretty straight for the balance of the term.

We were very much occupied in making preparaions for the Commencement Ball. For many years a ball had been given by members of the graduating class who were not religiously inclined. The sober sided, pious ones and the Faculty had tried to put it down for a long time but had failed so far, and there were a few of our Class who did not wish to have it. Accordingly we held a meeting of those who were in favor of a Ball; one of the first measures adopted was for all who wished a Ball to sign an agreement to support the same in every way practicable. We then proceeded to the choice of Managers, when we soon found that there was a dissatisfaction on the part of a few. Oliver desired to be elected First Manager and a few others wished him to have the office. The majority, however, thought differently and on proceeding to count the votes J. A. E. Merrill was found to be elected. This displeased Oliver and his friends so much that they voted for those whom they did not wish to be Managers and who were not well suited for the office.

We finally elected our number (eight) and the majority of us were determined to carry it through with the Board of Managers that had been elected, as we had first agreed to do. Oliver, Woodbury, and a few others would have nothing to do with the Ball even after they had signed the agreement. The Ball went on, however, and we had a most splendid affair of it. lam not disposed to boast but I am compelled to say that our Ball was fully equal to any ever given by the graduating class of Dartmouth College. The music was from Boston and a part of the Brass Band led by the famous Kendall, Our company, the elite of those who attended Commencement and of the surrounding country,—our supper, wines, etc. of the first order and all went merrily till near daybreak.

We graduated on the 25th of July, 1839, our number 61,—-just two less than the number that entered in 1835.

After graduating from College (Doctor) Butterfield decided to teach school for a while, and with that purpose in mind he went to Richmond, Virginia, where he published an advertisement in a newspaper stating that he desired a situation as teacher and that he was "a friend of Southern institutions." In this manner he secured a position as teacher of a school in Hick's Ford, Greensville County, Virginia. He remained there a year, during which time he began the study of medicine.

In 1841 he went to Washington, D. C., to study medicine at the Columbian Medical College, where he remained a winter, during the course of which he found time to visit the Halls of Congress and listen to the eloquence of the celebrated public men of that day, such as Clay, Calhoun, Adams, Preston, and others. He then returned to Lowell, Massachusetts, and studied with a doctor there, after which he completed his medical schooling at the oldest medical school in the United States,—the University of Pennsylvania: He again returned to Lowell and offered his professional services to the public, but not with the expectation of remaining permanently in that city as he had determined to settle in the South.

At this point in his narrative there are several lines erased, but not so thoroughly but that the words "a young lady" may be deciphered. After the deleted lines referring to the young lady, he goes on to say that he left Lowell, in disgust, for Natchez, Mississippi. Why in disgust? We can imagine, but I fear it is like what the Colonel's lady thought,—we shall never know.

Many a night on that voyage (to Natchez) did I sit and watch the stars and sigh for some kind, sympathizing spirit for a companion with whom I could exchange words of love. I was unhappy and little did I care for life now that I thought I had nothing to live for.

After looking around quite a bit, Doctor Butterfield settled in Washington, six miles from Natchez, Mississippi, his reason for settling in that particular place being that he had to settle somewhere and his funds were getting low. What pathetically inadequate reasons!

Here he was visited by the dreaded Yellow Jack, suffered much and came near dying. Over the story of his years in the South there hangs the fear and dread of Yellow Fever like a sinister spirit, periodically striking down great masses of the population. At a later date, when he was overseer of a plantation, he describes with much pathos the death of a young girl, daughter of the plantation owner. It is only as we sense and feel the bondage of a past generation to such a grim master that we realize the debt we owe to the medical men whose heroic work has forever laid this pestilential spectre; generations born to immunity and security are too easily forgetful of the deeds and sacrifices on which their security rests. Again and again Doctor Butterfield had the fever until finally, either by having gained immunity or by the adoption of a technique which avoided it, he ceased to be visited by Yellow Jack. His description of the Fever follows:—

My disease seems to be a congestive, bilious fever with deranged liver; I suffer very much when I am attacked and have come near dying several times. There is very great prostration, extreme pain and dizziness in the head, and pain in the back, with general derangement of the system. I am obliged to take calomel, blue mass, quinine, &c., and to apply mustard externally with cupping, and in this way I relieve myself in a few hours.

No matter how often he fell sick or how discouraged the outlook, he seems never at this period to have wavered in his determination to make a success of his chosen profession and in the locality that he has been drawn to.

If my mind wanders to the far-off scenes of my youth and the homes of my dear friends, when the hand of sickness is upon me, and if I wish myself back again, 'tis but for a moment that my heart fails me, for with returning health comes a renewal of my determination to persevere and not to turn back from the course I have marked out for myself.

Doctor Butterfield, after his stay in Washington, moved to Cold Spring, also in Mississippi. This was a small place and his practice was mostly among small planters and the negroes who worked as slaves on large plantations. The plantations were operated by overseers, the owners residing away, mostly in New Orleans. Of the overseers (he became one himself later) he says:

Of this class of men I have seen much since my residence in the South and I will record my opinion of them. Some of them are as high-minded and honorable men as can be found amongst any class, and they seem as anxious to discharge their duty as any lot of men I have ever known. This class I respect and I have the pleasure to say that I have some very good friends amongst them.

There is another class of overseers of whom nothing good can be recorded; they are ignorant, (to the last degree, some of them), they are vicious to the same degree ('all of them) ; all their study seems to be to try and deceive their employers so that they may not discover how they neglect their business and abuse their property. Drinking, card playing, and every kind of vice and dissipation is theirs. This class of men do not think much of your humble servant,—with them he is neither a physician nor a gentleman, and why ? because he does not encourage, either by precept or example such conduct as theirs and thus he merits their displeasure. They know of my opinion of their conduct for I am not slow to express it.

Wouldn't this last description have delighted the Boston Abolitionists ? and written by a man who knew what he was talking about. Perhaps old Simon Legree was not such a mythical character as the modern university critics, alive to every conceivable defect and deficiency, except their own pitiful lack of imagination, would have us believe.

It makes rather an interesting drama in a minor vein, this New Englander in the very citadel of the Southland, "friendly to Southern institutions." (Do you suppose President Lord's influence had anything to do with it?). To all intents and purposes a naturalized Southerner, yet viewing the men and practices around him from a moral standpoint. He had left New England in disgust, had always been antipathetic to the moral and religious life of the modified Puritanic society in which he grew up, and yet Conscience, the favorite child of New England's inner life went with him to his distant home as palpably as little Julius went hand in hand with away from Troy. Not easily does a man forget the scenes of his boyhood nor shake off the atmosphere in which he was born and raised.

(To be concluded)

Attorney for the College

*Student, Physician, Planter, Merchant; born in Lowell 1818, died in Boston 1892; lived in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Louisiana, Missouri; donor of Butterfield Hall and founder of Butterfield Musuem.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePROBLEMS IN EDUCATION AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

December 1925 -

Article

ArticleSCRAPS OF PAPER

December 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleRecent Reports in the Public Press

December 1925 -

Article

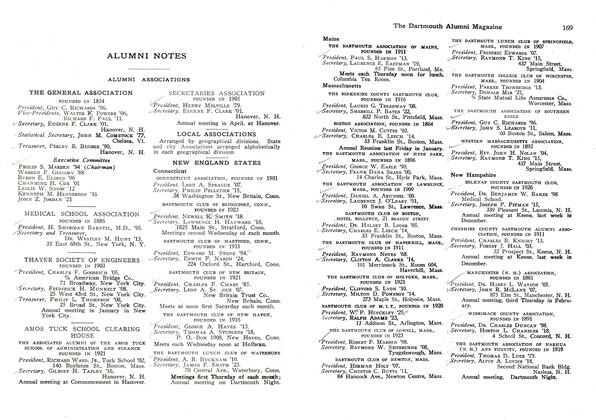

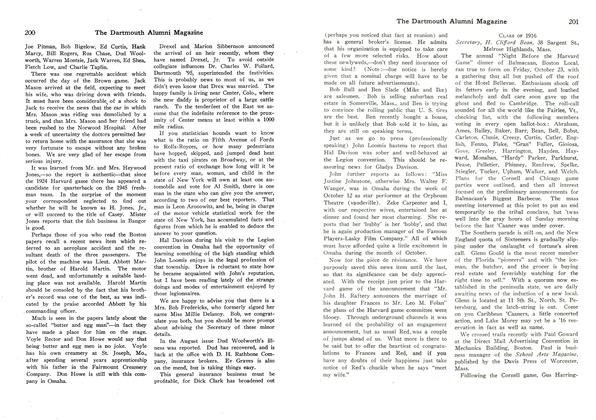

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

December 1925 By H. Clifford Bean