Recent reports in the public press indicate that it has been determined by the Harvard, Yale and Princeton authorities to question the practice of treating as "professionals" students who, as an incident to summer labors at hotels or other resorts, make use of their prowess as players of baseball. It is entirely probable that 99 out of every hundred college men—alumni and undergraduates—will say at once that this is good sense and tends to cure a defect which excessive zeal for athletic purity had produced. One has the uneasy feeling that one would prefer to hear the question exhaustively argued before joining in the cheers, but on the whole as a matter of first impressions there seems a great deal to be said for the abandonment of the old rule. After all, a student who plays a bit of incidental baseball during the summer in connection with other gainful work very seldom merits the classification of "professional" on that account—rating the occasional player on a summer-resort nine in the same category with Tris Speaker and Ty Cobb. One might boggle at receiving as eligible to the college team a man who had played most of a season with some obviously professional club; but there has always been a stout reaction against the rule which forced even the players in manifestly nonprofessional company to forfeit their amateur standing if they received any compensation at all, directly or indirectly, for their playing.

On the whole it seems a case for what the Supreme Court of the United States once vaguely called the "Rule of Reason." One may not be able to say with entire definiteness just where the line falls between professionalism and the estate of an amateur, but it is a matter on which one usually feels the distinction quite convincingly.

Of course the colleges need always to be on guard against the curse of professionalism in sport, but it seems probable that the least baneful of all the instances thereof have usually grown out of the summer resort baseball games. The man who is attending a particular college solely because some undisclosed principal, or enthusiastic group of alumni, is paying his tuition in order that he may add his strength to the teams is really much more of a professional than the bona fide student who ekes out slender resources by playing half a dozen times during the vacation season as shortstop in a team composed of others like himself. The evasions of such regulations have doubtless been many, by resort to noms de guerre. It must be a rare bird indeed among collegians who has not known of two or three such instances in his own day and generation. It may be better to recognize facts as they are, and wiser to define professionalism more strictly than we have been doing. To regard as a professional any man who has ever received a penny for playing in a single match seems much too lax a definition. In most cases such summer sports are a mere avocation—and professionalism might well demand that sport be pursued as a forthright vocation, or business.

How this contention will be received by that society with the very long name—the Amateur Athletic Union of American Colleges, or whatever be its exact title—remains to be seen. The propensity for some years has been to lean over backward, when the ideal would be an exact and rigid perpendicularity. The one real danger about relaxing the rules appears to be that sensible relaxations might be taken advantage of to an undue degree. One doubts that this would be a serious menace—more serious than that now involved by the use of convenient aliases. Meantime a boy who needs money and who can add to the proceeds of his other honest toil by taking part on a Saturday now and then in a local baseball game might conceivably be permitted to do so without ruining his status as a college player. There is small magic in the insignificant fee usually paid for such assistance, yet it has been made to appear like sorcery of the blackest. Our inclination is to invoke the "Rule of Reason" rather than the Rule of Thumb in such matters. Some summer playing would certainly suffice to make a college man a professional—and some would not. Much depends on the circumstances.

Voluntary chapel at Dartmouth is too novel an institution to warrant dogmatizing about it, but from what has thus far occurred it seems fair to say that the experiment is working better than most had dared to hope. It is probably well understood by alumni that the size of the college, the inadequacy of the chapel building to accommodate so many, and the manifest indifference revealed by the attitude of those who were forced to attend, have led the administration to decree an end to the compulsory morning "worship" which had endured from time immemorial, with the substitution of a voluntary service in the nature of vespers, daily and Sunday. The reports indicate that the Sunday service calls out an attendance of from 800 to 1000, while the daily afternoon service varies from 70 to 200 or over. Without exception, commentators aver that the chapel atmosphere has completely changed, so that those who are found at the exercises are attentive, decorous and eager to hear, where formerly one of sensitive soul was forever being disgusted by the unconcealed indifference of the congregation. Of course in the latter case the congregation was vastly larger, but it was certainly not strong on churchly behavior.

Which is better—a big congregation of students who are in chapel only because they are forced to go and who act badly while there, or a small gathering who attend because the service appeals to somet hing in themselves, which possibly they cannot analyze but which they know to be real? There is no doubt concerning the answer, even in the mind of those of us who nevertheless sigh for the departed days. The few who find satisfaction in religious services would be there anyhow. The many are simply relieved of an incubus and are very likely glad of it without being bettered either way. It was silly to pretend that they got any religion out of it, but they aren't getting any more now that things are changed.. The real benefit accrues to those who prefer to enjoy the formalities of public worship unbothered by the rustling of papers, the whispering of thoughtless conversationalists, and the occasional excesses of the outright boors.

The service evidently has taken on a somewhat more elaborate character, with a processional hymn; and the speakers at such meetings appear to be a unit in expressing satisfaction with the new arrangement.

The expedient of calling the Alumni Council to meet this fall in Chicago, rather than as customary in other years in Boston or New York, had as its occasion the fact that the football game at that city would probably call many eastern alumni thither at that date, and as its major justification the feeling that the western members of the Council ought not to be asked to do all the long-distance traveling. Chicago, as lying close to the geographical and population centers of the country, entailed a journey such as the eastern components have not before been called upon to make, and meeting there sensibly reduced the burden for those who hitherto have been forced to cross the country if they were to bear a hand with the business for which this body exists.

Beyond doubt it is advisable to make it possible for the great majority of the membership to be present at meetings with the minimum of personal expense and the smallest possible sacrifice of time. As the alumni body has grown in size, and as its importance to the administration of the affairs of the College has augmented, it has come to be less and less likely that a general alumni meeting, held at Hanover during the Commencement season, could do much more than pretend to function. Hence the virtual adoption of a system of "representative government," at which the alumni body is represented by regional delegates, in number and qualifkation sufficient to insure a genuine consideration of business which in older days the whole alumni might have managed to do.

The MAGAZINE would once more stress the vital importance of insuring the continuance of the Council at its present high level of capacity. It has come to be the recognized mouthpiece and right arm of the whole number of our alumni. It has been entrusted with the all but exclusive responsibility for the presentation of alumni trustees. On its intelligent and fully representative character a great deal depends. It is therefore the manifest duty of the regional bodies to provide themselves with representatives in the membership of the Council in whose judgment trust may be reposed, who will probably be able as a rule to give their personal attendance at the two or three meetings which occur during the year. At present the body is creditably strong and it should be easily possible to main- tain it in that useful estate. Membership should connote a healthy interest in Dart- mouth, a genuine regard for the intellec- tual as well as the material and athletic up building of the College, and a personal readiness to make some sacrifices of con- venience and money in order to attend upon the by no means frequent delibera- tions of the organization.

By the time these lines see the light of print and circulation the football season will have largley passed into history. At the time of their writing the record remains incomplete. Nevertheless, enough has happened to date to warrant an abstract encomium of the progress achieved in the line of developing this traditionally popular sport under adequate and ingenious generalship. The game at Cambridge was to thousands of people a revelation of possibilities not before comprehended in the matter of opening up the game—important not alone as a matter of tactics leading toward scores, but also and very appreciably as a matter of enhancing the pleasure of spectators. Old-style footb all, which usually meant three scrimmages and then a punt, had its power to enthrall and excite but was to many ungifted persons rather boring after a halfhour of play because of the repetitions, the sameness, the obscurity of the playing. The open game, in which Mr. Hawley's generalship has produced such remarkable results, has proved a much better game to watch, whatever be thought of its effectiveness in the scoring column.

All colleges now adopt, we believe, the custom of numbering the players so that the people in the stands may know who's who. Harvard, which had held out for some reason against this method of individual identification, numbered her players this year and probably will continue to do so. This is purely a matter affecting the thousands in the grandstands. It enables them to know, by reference to the score-cards, which player is which—always a desirable thing. To the actual players on the field it makes no conceivable difference either of detriment or betterment..

One must be prepared, as always, for the criticism that college football games are too much treated by all hands as public shows with a highly commercialized side; that the circumstances tempt toward lavishness in equipment; that the coaching system has been overdone; and that the whole idea has drifted miles away from the original theories of intercollegiate sport. Whatever one may say or think of the underlying merits of these contentions—and one must admit that there is more or less plausibility in some of them—nothing is clearer than that criticism is foredoomed to be futile. No remedy for whatever defects there are is in sight—and the defects themselves seem to us not to be doing the exaggerated harm that some critics are heard to affirm is done.

There is practically no "professional" football—none at least that greatly interests the general public. The public looks toward the short college season for its satisfactions in this particular and that not unnaturally imposes a difficulty which irks the exacting academician. One might prefer simple contests of home-grown skill before gatherings representative of alumni and their sisters, their cousins and their aunts, as contrasted with the modern assemblage of all the world and his wife, in numbers sufficient to populate a good sized city. Much has been done—perhaps all that can be done—to curtail the abuse incident to the sale of tickets, without answering completely the objections. The avid sports-writers of the daily and Sunday press' invariably overdo their part of the problem. There is possibly too much anxiety to make the football season produce thes revenue required to finance the entire sporting program of every college for the whole year. But is all this really worth bothering about ? Does any one really want to give it up? How would such a proposal fare on referendum?

While there is something to regret about the spectacular guise now assumed by this particular sport, we cannot avoid the belief that it is what the overwhelming majority want and that its actual detriments are inconsiderable.

Out of a clear sky came the recent thunderbolt of welcome news that although there was no specific money in sight to finance such an operation the Trustees felt that the need for a new library at Dartmouth was so pressing that the undertaking could no longer be postponed. Therefore it was voted to proceed at once to the construction of a proper building—and the cost of such a building seems to be estimated at not far from a million dollars.

The necessity is apparent to every one. It has been increasingly uncomfortable to feel that, while the College had a mammoth gymnasium and an adequate athletic field, commodious modern dormitories, laboratories and so forth, it was worrying along with a library no larger than Wilson hall—which had been barely adequate a generation ago but is now entirely insufficient to house the volumes owned by the College and at the same time serve the students and faculty as a library should. The College is said to own at present 213,000 volumes. Ordinary healthy growth will mean that within a score of years there must be found room for half a million books. Hence the decision of the Trustees to set about the provision of a new library building, which shall not merely suffice for conditions now prevailing, but also promise adequate service for the ensuing halfcntury at least.

This important step is one which we believe every alumnus will greet with a cheer. It may mean the borrowing of a million dollars, which will entail a very considerable interest charge on top of the need for arrangements graduallly to retire the principal—but it is one of the things for which we honestly believe the College cannot afford longer to wait. An institution of learning devoid of a proper library is poor indeed. The library is inevitably the temple's inner shrine. The Trustees have done well to face this pressing problem, and their courage in attacking it as an imperative current necessity merits not only the sincere praise of every alumnus, but also the active cooperation of all in whatever ways may become appropriate. One has always the vague hope of considerable future gifts, of course, which may be made available to meet this purpose; but in any case, even before such appear to be assured, a library will be begun and the money, if need be, will be borrowed. The point is that Dartmouth cannot, without impairing her own repute, put off any longer the cure of this prime defect in an otherwise splendid plant. It has been the one glaring omission—the one thing Dartmouth men have felt they must apologize for.

In a way one may be glad for the past delays, because thereby we have probably escaped the infliction of a library at once badly designed and 'architecturally inharmonious. A quarter-century ago, one fears, we should have built a structure which by now we should regret. The mistakes of others should suffice to make us wise. The later development of the Dartmouth plant has been along sound architectural lines, and the library is certain to adapt itself thereto.

It is impossible to pass over without comment the Trustees' admirable choice of Clarence B. Little 'Bl to life membership in the Board of Trustees, in succession to the lamented Dr. Gile whose death was chronicled last summer. Mr. Little has been an earnest and enthusiastic servant of the College, giving to it much of his time though a busy man and resident so far away as Bismarck, North Dakota. Mr. Little's accession to this permanent estate as a life trustee has left for the Alumni Council the task of

nominating a successor as alumni representative; in fact two such positions have to be filled by the Council under the new system of elections—that of Mr. Little, promoted as above, and that of Morton C. Tuttle, whose present term expires next June. Mr. Tuttle is serving at present the unexpired term of the late Harry H. Blunt. Particulars as to the action taken in these matters will doubtless be found in the reports of the Council deliberations at Chicago, as printed elsewhere in this issue.

Another cause for congratulation is found in the offer of Howard Clark Davis 'O6 to present to the College a "Varsity Field House"—a building to be constructed in connection with the athletic field for the purpose of affording, among other things, adequate hospitality to visiting teams. The lack of proper facilities for this purpose has been sorely felt on many past occasions, and the projected gift by Mr. Davis will be cordially appreciated by all who wish to see Dartmouth do the honors worthily for those who come to Hanover to play against our various athletic teams. The facilities will include dressing rooms both for the home team and for the visitors, as well as a commodious living room for use by the players before and after the contest—and perhaps as well between the halves of football games. Naturally this equipment will fall into the general jurisdiction of the Green Key as the official dispensers of hospitality to our visitors.

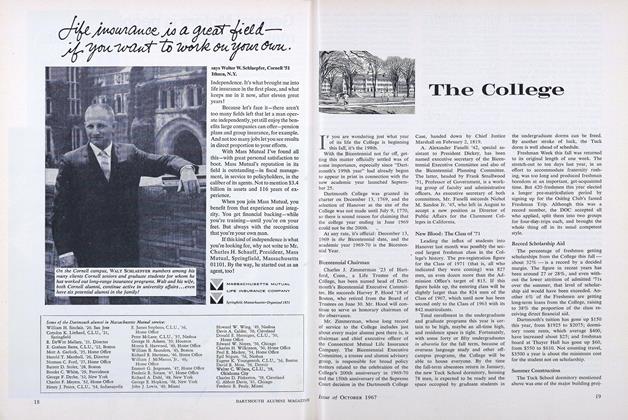

Just before a Big Game in Hanover

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSHORT PAGES FROM ONE LONG LIFE

December 1925 By Roy Brackett -

Article

ArticlePROBLEMS IN EDUCATION AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

December 1925 -

Article

ArticleSCRAPS OF PAPER

December 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

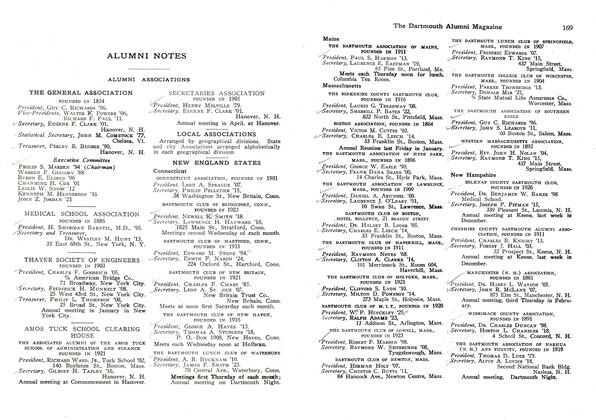

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

December 1925 By H. Clifford Bean