"No student shall be allowed to chew gum in the College buildings or on the College grounds; and playing marbles, throwing spitballs or going swimming within the College yard or near the buildings is prohibited between the hours of four and seven P.M." This is under the headline, "RULES PERTAINING TO THE OCCUPANCY OF COLLEGE ROOMS. (Printed by order of the Trustees.)" And here is another rule,—"All sweepings and rubbish shall be deposited with the Clerk of the Faculty for chemical analysis, in order that the moral character of the students may be taken into account in making out the marks." Were the Trustees candidates for Waverley or Bloomingdale with five clergymen on the Board! But this is a set of rules properly printed, spelled and punctuated, at least fifty-three years old. Again, "The time for which the rooms are rented shall expire at the next Centennial of the College." And, The repairs of all damages to the rooms shall not be paid for by the occupants unless it shall appear that they are in no way at fault in relation to such damages.' The key to this foolishness? The "Rules" are a parody word for word (with exceptions) of a genuine document promulgated at about the same time. The boys were "spooving" the Curatoresreverendi at honorandi (as said all the salutatorians), and it was perilous enough in the third quarter of the nineteenth century to be pleasant sport. We learn here by the internal evidence what games the students possibly might play, and that even at this remote period suspicion lurked that character had some definite relation to marks.

If four years of college life is a generation, ten years antiquity, and fifteen years old traditions, surely records which have been lying forgotten in an old portfolio more than fifty years are ancient and therefore venerable. As insignificant once as fleas in the mummy cloth of the Pharaohs they may now be searched for the intimate relics of a former age. Once they would have served to start a fire; now they are flotsam from the nevermore.

Behold then, written in an absurdly boyish hand, the report of the treasurer of the baseball association as it was made to a college mass-meeting in June, 1872. It balances with a total of $200.75. In 1924 the total was about $14,000. The treasurer at the beginning of his office took over a debt of $47, (a familiar condition until an Athletic Council, of which by a strange coincidence this same treasurer was a member, took charge, gradually extinguished scattered debts of $3500, and started a reserve fund for other branches of athletics and deficits generally.) This treasurer paid the debt, and well and truly delivered to his successor a cash balance of 76 cents. It is evident that this treasurer might have been an unsettling and detrimental factor in big business by mismanaging the office of receiver and putting embarrassed organizations upon their feet instead of skimming off the cream and retiring, or "freezing out'' the rightful owners and reorganizing.

This was the period of undeveloped and spontaneous baseball. About ten men constituted a "nine" instead of twenty-five or thirty. Some players weakly paid their own expenses and even bought their own bats. The pitcher heaved the ball as forcibly as he could with his hand below the hip. The unarmored catcher stood up to the bat on the third strike and took his punishment, sometimes in the eye. It was deemed by some a clever play to stand back of a twisting foul and catch it on the first bound, thus putting the striker out. Fielders and basemen who attempted to protect their tender hands by glovesjust any gloves; for none were made for the purpose—risked their reputation as he-men of brawn, and unless their skill was conspicuous and their vigor forewarning were in line for the application of an opprobrious word (stated for crossword puzzle graduates) of five letters of which three were s's and the other two were the same in sound. At this time evil had not crept into the baseball world and teachers played on school' nines even with approval.

As Mr. Pender in his excellent record of Dartmouth athletics left uncelebrated this nine of the summer of 1872, I will give it a chance of glory with the others. It was constituted thus:

E. J. Underhill '73, captain and catcher, L. G. Farmer '72, pitcher, G. H. Fletcher '72, short stop, E. S. Ball '74, first base, S. H. Burnham '74, second base, W. G. Eaton '75, third base, G. A. Merrill '72, left field, G. H. Adams '75, center field, C. O. Gates '74, right field, E. J. Bartlett '72, treasurer and substitute.

A game at Amherst was impending, and for reasons now sunk in oblivion dissention weakened the nine. By selection of Captain Underhill confirmed by the College in mass-meeting assembled, the treasurer who had recovered from an injured hand and was on the verge of excellence (in a less proficient age) was requested to go along and pay the bills and act as substitute.

Those were the days of homely hospitality; and after kind entertainment at their various fraternities the members of the visiting team were billetted among the proud possessors of double beds. The bed-fellow host of the treasurer, either from a guilty conscience or from overfeeding in the evening, tossed and growled and gave forth jarring sounds produced by loose vocal cords or a flapping soft palate or something which murdered sleep; and thus perhaps the whole nine was enfeebled. At any rate the game was disastrous. Although the present suspicious aloofness of visiting teams is to be regretted, a return to the old time hospitality can not be advised.

Attention suddenly shifts to a little sheet wholly devoted to the unpleasant subject of absence. Who said absence made the heart grow fonder? "Excuses and Absence." "Discipline and Absence." "Studies and Absence." One would think that without absence excuses, discipline and studies could not be had. But the brusque and hard-hearted use of "must and "shall" in this little flyer issued by a thoughtless faculty belongs to a barbaric age which had not learned to blush and ignore every subject which interferes with self-determination.

Stop on this only to drop a tear for the sad lot of poor old Prexy. "Absence at the beginning and end of a term can be excused only by the President." Poor old Prexy, thus made a mark both ways for the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune! Modern deans who have taken a special course in life-saving, and who do their work surrounded by barbed wire defenses of rules and overcuts anc supported by hard-boiled committees on discipline or administration or general negation have shed tears "very salt and bitter and good," till their eyes were dry, over the pest thus fastened upon Prexy. And Prexy, as he was endorsing bills, answering letters in his own long hand, writing a sermon, preparing a lecture, cramming for a recitation in Butler's Analogy, had to shut off the flow of ideas and listen to all the fairy stories about dentistry, family reunions, new clothes, helping father in the store, impending measles, earning money to pay term bills, attending grandma's funeral and, worse yet, read letters from ag grieved parents who pressed their proprietary right to have the boy at home when they wished. Every specious appeal resisted by Prexy might germinate into dis content; blossom into hostility and riper into a disgruntled alumnus. If, however to relieve his weary soul and perhaps tc make a friend in the cold world he now and then relaxed, he had created a precedent—awful thought—and had invoked a lifting of faculty eyebrows, a shaking of faculty heads and the exchange of soft intimations that the president was getting sadly weak and something would have to be done about it. And then he would beg someone to take chapel for him, and remind someone else to have a fire in the senior room on Friday morning, and go off to raise some more money for the Newcomb professorship.

Behold a schedule of examinations for the end of November, 1868, dry as Mr. Anhydrous himself, but beaming with more side lights on history. There was an examining committee, three ministers and one esquire, all of whom lived near enough to arrive by nine o'clock Monday morning without travelling Sunday. I see that an irreverent classmate—I think I know who it was, and he makes a very handsome contribution to the Alumni Fund every year—has written into my copy of the schedule an additional name, "Prof. Bumford, Good Hope, Africa," which though not pointedly scornful seems slightly derisive, the examinations were all oral, and as many and no more were going on at the same time as there were available witnesses. No doubt these vessels of the humanities having their expenses paid and enjoying the hospitality of the Hotel Frary, if they had not intimate friends on the faculty, had as much fun out of the joke as did we. We knew that they knew nothing of the subject; perhaps, it occurs to me now, they knew the same of us. We handed them books with surpassing courtesy, and had our little jests about their holding the greek texts upside down, going to sleep while we expounded quadratic equations and asking funny questions "merely for information." I don't feel so superior now. People do pick up a little something in the first twenty or thirty years after they are out of college. I wonder that we survived the perilous strain on our endurance. Three consecutive periods finished the whole terrible affair. A senior who began at nine in the morning might be playing croquet by three if the weather permitted.

And here are lists of the Juniors who made exhibitions of themselves in the springs of 1870, 71, 72. The young collegians of these later days have paid too little attention to the words of wisdom and often of prophecy which have come thundering down the half century from these forensic explosions. Only a few classes were worthy of these great opportunities, and they were all included within the years 1866 to 1877.

When the baseball season—what there was of it—was opening, in the mid-afternoon of mid-April, sixteen, or it might be seventeen lads—they seem very young to me—put on each his other suit and assembled in the College Church, where to a meek and dutiful audience they gave earnest expression to modern thought upon topics selected by Professor Sanborn. If you inquire how those adolescent utterances differed from today's, I surmise that then there was less introspection and self-consciousness, and more, perhaps too much, respect for authority. I am sure that it was a period of estheticism, because I remember a cartoon in Punch with the legend beneath, "Postlethwaite sick of Lillies and trying to smell a Sunflower."

It would be edifying to quote all the subjects of Junior thought and expression and to show their relation to the modern world, but a few must suffice. I observe that I myself had serious views upon the Consolidation of Railroads. I cannot now recall whether I thought the railroads should or should not be consolidated. One sentence which I thought contained a vigorous and timely demand comes back to me now, "The government must take, own and operate the railroads." I wish to recall it at once before anything is done about it. And at present I think that some railroads should be consolidated and some should be disintegrated and some should be left in peace to compete with the jitneys if they can. I see that a distinguished and retired superintendent of McLean Hospital discoursed upon the notion, if I can disentangle the title of his Latin oration, "Nature can't keep a secret if the good student worries her long enough." See what has come to light since that day fifty-four years ago! He was right. Our second in rank, early dead, anticipated "Creative Chemistry" with "The Romance of Science." Our neurologist whose reputation extends across the seas prepared the world for what was coming through "Germ a n Unity," with a war for illustration. And if the nations had been influenced enough by the opinions of our learned doctor of laws upon "National Antipathies," and of our leading barrister, if I may use that word, upon "Standing Armies," how much suffering would have been avoided ! Even now the ex-mayor of Haverhill might well press his views against "Special Legislation." I cannot read the little crooked letters from which our solid valedictorian set forth doctrine which I am sure was sound even though no auditor knew what it was. Without additional samples it becomes evident that we were right there with the goods as modern scholars sometimes say.

Banefully, this intellectual feast became to the appetite for sensation secondary to urge for the preliminary cocktail, —the mock (or muck) program. Adequate analysis of these peculiar documents has never been published, and probably never will be until those monosyllabic and consonantal words now seldom written or printed displace from literary language their more elegant Latinized synonyms. They were edited in indecorum, printed in secret and stealthily circulated in the darkness of the night. They were gathered in by shuddering collegians with a horrid but luscious wonder how much they were going to be shocked.

Notwithstanding the threat in their title they had no connection with the Exhibition except in occasion. Names upon the official program did not often appear informally. Once was enough. Occasionally some joke was magnified or distorted, or some spite was gratified at the expense of an orator. But painful as it was to find high marks associated with good morals it must be said that others were more vulnerable to scandalous attacks than the sixteen speakers, and the silent majority were preferred targets. All kinds of immoralities were ruthlessly revealed or malignly charged. It might have been Virtue rebuking Vice, but it was a drabbled and ribald Virtue using the language of the slums. Considering the latitude of the personalities and the broad, the limitless field from which the critics could pluck their malodorous bouquets it is amazing that so little humor is exhaled.

In itself the next fragment with its fifty penciled words has nothing worthy of survival. But it is rich in suggestion,—of simple pleasures, innocent ambition, blameless adventure and the pace that uplifts. Those are tough and teasing words, —"ecstasy" and "apostacy," "paralyze" and "apologize," "suspicion" and "ebullition," "singeing" and "allegeable." This is a relic of a mania that swept the country from east to west and tangled the brains of the proudest. Only those who after spelling correctly all their lives were caught in unfamiliar vocabularies could tell of the traps in the English language. Authors, divines, teachers and even proofreaders were slaughtered by the wily clump of letters. Phonetic spelling had no standing in a match, and the haughty prolocutor gave no heed to authority outside of the book in his hands; that could be argued next day.

The Spelling Bee had two branches,— the Spelling Down showing individual prowess and bringing out home talent, and the Spelling Match depending upon organized proficiency and arraying neighborhood groups in bitter rivalry, until the doughnuts and cider were served.

O, don't you remember that contest, Ben Bolt, between North and South Hebron in the town hall at Hebron Center, when first selectman Boggs gave out the words, and Judge Torte, Professor Nowell and Miss Lucy Sweet of the third grade were yet standing for South Hebron and only Betty Bell Kendall remained for the north village. The match was practically over, and as soon as Betty Bell sat down the social would begin. According to the rules the words alternated from one side to the other, so that Betty Bell had to spell three words to one for each of her opponents. It was time to stop, and selectman Boggs started the tricky words. The judge got "allegeable," which, naturally, he managed very well. Betty Bell was all there, intense but calm. Betty was of good stuff which comes out strong in emergencies; nevertheless she was only fourteen years old, and as she stood there with the braids hanging down,, her back and with a white apron over her plaid dress her best chance seemed to be in a quick and painless conclusion. Her next word was a hot one,— "trafficking"—but she disposed of it with the serenity of an adding machine. To the professor, who had once written a book, "deleble'' was given. It was an unfamiliar word to him, and for the moment he could not place it. So he cleared his throat and inquired, "What was the word ?" not because he did not know but because he hoped the repetition would give him light upon that indistinct second syllable. And it did; the vowel was plainly "e." "Delleble," he spelled; and the word went to Betty Bell who turned it off as though someone had pushed a button. Miss Sweet got "mortgaging," and Betty Bell "ignitible," and all was well. Selectman Boggs was not as guileless as he looked, and he sprung "indelible" upon the Judge. Of course that was fair, but there was psychology in it, though they did not know it then. "That is an easy one," thought the Judge; "in" means "not," not deleble," and the little girl has just got by with "deleble." He spelled as he reasoned and had to sit down. When the word went to Betty Bell she lowered her voice so that Mr. Boggs had to ask her to "speak up." It was a time in which young people were taught to be gentle about correcting their elders. Now only Miss Sweet and Betty Bell were left, and they alternately evaded the tripping words until it seemed probable that one of them would have to be brought down with a club. "Desperate" and "separate" caught neither of them, and the discouraged first selectman Boggs propounded to Miss Sweet "syzygy." Whoever heard of such a word! for the first time Miss Sweet had to stop to think ; and thinking failed to help her because she did not know the word. A gleam came into Betty Bell's gray eyes. She had guessed right. That dreadful word was the first word in the third column on the last page of Webcester's Universal Spelling Book. The more Miss Sweet thought the more she could think only of "sizzle." It was a tense moment when she began "siz—"; then she knew by Mr. Boggs' face that she was wrong, but corrections, if she had any, were not allowed. Betty Bell had no idea what the word meant, but she knew that there were three y's in it, "sy-zy-gy." The match was ended with tumultuous applause even from the losing side, and some who I suppose had the right were seen almost to smother Betty Bell with kisses. She was not triumphant; her loyal little heart was glad that her folks had won the match. But she was a conscientious child and she wondered whether it had been quite fair to make a guess and study that particular spelling book all the day before the match.

As a series of connected events the incidents of Commencement fifty-three years ago are of mild interest to the survivors of the class which graduated then, and probably of no interest to others. They furnish, however, historic atmosphere and a basis for philosophic reflection. The underlying theory of the time was that the assembled multitude required brain-food, sociability and bodily nourishment. Hence amplitude of prepared talk under the names of sermons, addresses, discourses and orations, large open periods for conversation, and many free and delectable collations. Sunday is mentioned on one of- these scraps of paper as "the Sabbath" (a day of rest) ! A sermon occupied the forenoon of this Sabbath with no skimping development of the theme; the central event of the day was the baccalaureate discourse by President Smith at eactly 3:15, upon the text, "Let patience have her perfect work,"—not much of an inspiration to a go-getter but doubtless balanced in the good president's mind with other more energetic counsel. And in the evening a reverend doctor had an inning with the Theological Society, which was a solemn predecessor of the modern Christian Association and which gathered in sixty or seventy of the most pious in the whole institution but not the harmless and more frolicsome lambs. Monday was another day for rest, and for the arrival of those who did not care for sermons and who couldn't play golf because at that time there was no golf. Even Tuesday was easy until class-day exercises, which began when the band arrived on the afternoon train and continued until stopped by darkness or the Chandler Commencement where secular brains were fed on "The Mont Cenis Tunnel" or "Scientific Training as Related to Manufactures."

On Wednesday came the real test of endurance for which these earlier days had been preparatory. At ten o'clock, after the alumni meeting, the Rev. C. A. Aiken, D.D. addressed a comparatively fresh Phi Beta Kappa audience upon "The Rights of Doubt" which he asserted were illegitimate when doubt assumes to be authoritative instead of merely protective. Then came a eulogy on President Lord for a sympathetic summary of which the reader is referred to the Boston Advertiser of June 27th, 1872. The great events of the days were the oration by Edward Everett Hale and the poem by Walt Whitman before the united literary societies, the Socials and the Fraters. Mr. Hale's address was a highly satisfactory plea "for a Liberal Education as a Basis for Special Training." "Whitman appeared in his customary eccentric garb with a part of his brawny breast bare; and his long white gray hair and tawny beard set out by his Byronic collar made his head and face a study. His poem was the thread-voice or spine of a new series of chants illustrating 'an aggregated, inseparable, illustrated, vast, composite, electrical, democratic nationality.'" (At this point one thinks a comment upon the contrasting inspiration of the poet Whitman and the fatuity of the peripatetic Pratt.) The audience treated Walt kindly, but his poem was not appreciated. One elderly alumnus was heard by a limited circle to mutter, "Words, words; nothing but words!"

A concert in the evening refreshed the multitude for the real purpose, climax and end of the festival.

On Thursday twenty-four young gentlemen addressed the floating population of the church from ten o'clock until half past three, and I will say, hoping to arouse the envy of those who hold the front of the stage today, that the Boston papers highly commended their efforts. Then all who were entitled and at this time physically competent marched past the Milway Plaisance at the south of the Green, past the tents and the peanuts and the sandwiches and the pink lemonade and the "try-your-chance" barkers, into the old Dartmouth Hotel where Mrs. Frary reigned supreme. Here, history says, were brief speeches from eight speakers, one future president of the College, Dr. S. C. Bartlett of Chicago, and two who were then or later professors, Senator Patterson and James F. Colby.

Recurring to the chief orators of the day, the speakers in the church, I can mention only one of their timely topics, "Our Account with Posterity," by one of our serious thinkers. I wonder how it has been kept.

A familiar autumn visitor in Hanover John Spaghetti

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSHORT PAGES FROM ONE LONG LIFE

December 1925 By Roy Brackett -

Article

ArticlePROBLEMS IN EDUCATION AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

December 1925 -

Article

ArticleRecent Reports in the Public Press

December 1925 -

Article

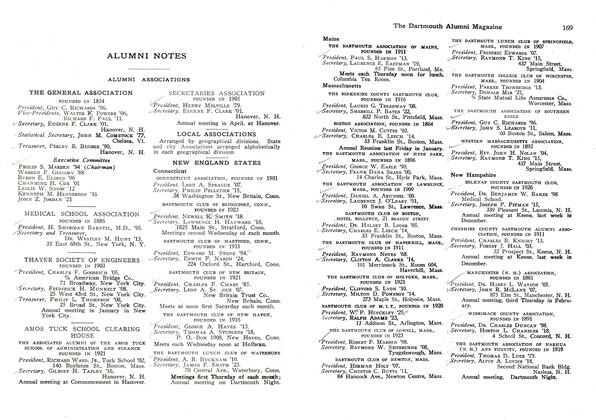

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

December 1925 By H. Clifford Bean

Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

Article"WHAT EVERY PROFESSOR OF SIXTY SHOULD KNOW"

January, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE OLD SONGS

April, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Sports

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

NOVEMBER, 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY MEETING

DECEMBER 1927 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72