exercises of the One Hundred and Fifty-Seventh Commencement, Dartmouth College brought to a fitting close what was said by President Hopkins, in his remarks to the Alumni Council, to have been "perhaps the best year, scholastically, in the history of the institution." If so, a notable period for both material and intellectual progress has been experienced- for materially this has been one of the most satisfying of our college years. The steady maintenance of repute as evidenced by undiminished numbers of applicants for admission may be cited, along with the gratifying amounts of money, given for special purposes and raised by the alumni for the Alumni Fund, as evidences of the degree to which Dartmouth continues to command the confidence of all interested. If, in addition, the president feels that a genuine advance is being scored in the matter of scholarship—and he says he does so feel—there is every reason for the proper satisfactions.

We say the "proper" satisfactions by design, for we feel that satisfaction is one of the easiest things to overdo. If by satisfaction we were to mean a feeling which inspired us all to rest on our oars, that would be overdoing it. If it were to prompt a widespread conviction that at last we had reached a sort of elevated plateau, along which momentum would suffice to carry the College for an appreciable time, that would be a bad thing. It is one of the dangers attending Dartmouth's present situation—what one of the Alumni Trustees phrased rather pithily as "the danger of feeling that 'everything is all right' so that nothing remains to do." Everything is all right, in one view of it to be sure. The College is doing excellent work and is deservedly popular, to all seeming, with the country. In another view it has not yet caught up with its growth; and until it has done so, fully and completely, it has an abundance of needs which cry aloud for satisfaction. Our past achievements, then, require to be viewed as incentives to complete the job, rather than as excuses for laying it aside as if it were already done.

The hardest persons to help are those who, to outward view, stand in no need. The necessities of Dartmouth, we should remember, have been but partially supplied, and always will be but partially supplied, so long as' the endowment underlying the present college is so far short of the requirements, the while it remains necessary for a considerable proportion of the 2000 students, now recognized as forming the maximum the College can profitably care for, are forced to room in other than college buildings. Beware, we would adjure you, of feeling that we have reached more than the lower shoulder of our mountain. It looks like a summit, but it isn't.

To those who saw and talked with the late Professor John King Lord during Commencement week, the news of his sudden death within a few days thereafter probably came as a greater shock than to others. Seemingly in his usual health and spirits during the period devoted to graduation exercises, although admitting that a recent attack of influenza had left him feeling somewhat less active than was his wont, Professor .Lord had apparently developed a weakness of the heart which exacted its penalty while he was on a vacation trip to Wonolancet. It is needless to say here that in his going the' College has suffered an unusually heavy loss, for few men in its history ever served it longer and none more faithfully. His activities were by no means confined to the teaching staff, with which he was connected for a generation or more. They included a term of active administration as temporary president during the interregnum between the presidencies of Dr. Bartlett and Dr. Tucker; a most productive service, as a member of the Board of Trustees; and a further service, quite as important as any, in his carrying forward of the History of the College, begun but left unfinished by the late, Frederick Chase. Familiar to all Dartmouth men from the '6o's to the 1920'5, Professor Lord probably enjoyed a wider acquaintance among Dartmouth alumni than any other man of recent years, and was by them universally esteemed. Dartmouth without ''Johnny K.", as all affectionately called him, will never be quite the same for those who knew the college in his time. On it he left the indelible impress of his character, and many a monument exists to him aside from the speaking portrait by the late Joseph Decamp now hanging in the President's office at Hanover. Space does not suffice at this time to body forth all that the MAGAZINE would like to say of him— but perhaps there is no need to say it. With John King Lord there passed from earth one of Dartmouth's most faithful servants and most devoted sons.

The list of gifts announced at Commencement included, in addition to the anonymous donation of a million for the new Library, an item referred to as "Anonymous Fund No. 2" estimated at $725,000 and subject at present to an annuity equal to the income from the fund, so that the full benefit of such benefaction is postponed during the life of the unnamed annuitant. Such gifts are increasingly common and are to be highly commended. They enable an intending benefactor to insure the College of its gift and contribute to the present satisfaction of the donor, while reserving to him the necessary use and enjoyment of his income during the period of his own life.

In addition to this there was a long list of other donations, ranging from $160,000 or so down to $lOOO, including at least two notable buildings which have already been begun—the Field House, given by Mr. Davis of 1906 for the more adequate housing of athletic teams, including the future visitors to Hanover; and "Dick Hall's House," given in memory of their son by Mr. and Mrs. E. K. Hall, which is to stand near the Hospital and afford shelter for such students as are ill without being forthright hospital cases. Other noteworthy additions to the visible plant, subject to speedy completion, include the new residence for the president, into which it is expected Dr. Hopkins and his family may be enabled to move before the opening of the next semester.

The Alumni Fund at Commencement time, with many items still to come in, was announced as approaching $90,000, with every indication that the quota set ($110,000) would be attained if not exceeded, and with the probability that the percentage of contributors would be very nearly equal to the 72 per cent scored last year—a most gratifying figure, but one which we hope may yet be exceeded, even though at that rate it greatly exceeds any other Alumni Fund statement by other colleges. When three-quarters of the living graduates of an institution like ours annually contribute to the maintenance of the College, it indicates a healthy condition; and 80 per cent would be even more gratifying, of course. To this end it may be pertinent to remind all readers that a single dollar, if it represents a genuine love for Dartmouth and is all a man can spare, is just as highly regarded as any other gift and helps to bring nearer to the attainable degrees of perfection this annual test of our graduate loyalty.

Space is insufficient at this time to discuss in detail an interesting article in July Harper's on "The Pestiferous Alumni" by Percy Marks, best remembered for his novel, "The Plastic Age," as published a few years ago revealing the author's views of undergraduate life. This arraignment of average alumni, which appears to us to have an uncomfortable amount of truth behind it so far as facts go, may be subject to other interpretations than are put on it by Mr. Marks; but it must suffice here to remark that the author seems to make a flattering distinction between the alumni of colleges in general and those of Dartmouth in particular, in that it is admitted that President Hopkins has succeeded better than any one else in educating his alumni body to a helpful interest in Dartmouth as an intellectual institution, father than one which is to be taken into account only as a place where boys play intercollegiate "games with noteworthy success. We suspect Mr. Marks would not admit so much if he did not actually believe it, his disposition being apparently to see but little virtue in college graduates in the mass. Whether this failing on the part of alumni in general to reveal the stamp of culture and intellect is in some degree an indictment of those who attempted their education while they were still in college, may be postponed for consideration at some other time. So far as concerns their education as alumni, it seems that a special palm is awarded the President of Dartmouth by a hand by no means lavish in its bestowal of such praise.

Is there another language spoken by a civilized nation which is comparable with the English on the score of tolerance toward slovenly use? By this is not meant that pedantry which would debate whether, in the foregoing sentence, one should say "comparable with" or "comparable to." The reference is to forthright abuses of construction as to which no doubt exists—offenses against grammar, solecisms, colloquialisms of no recognized standing and the like. There seems to be a feeling that to be scrupulous in such matters marks one as precious, or ostentatiously affected. One hears a speaker here and there referred to with appreciation as "using such good English" that it singles him out for remark. Such a man is head and shoulders above his fellows; and apparently his fellows feel no sense of shame.

It is unpleasant to feel that in this respect the colleges are indictable to some extent. Their product of graduates, supposably men who for four years have rubbed elbows with liberal culture, cannot be called notable for polished speech. If culture has been acquired it all too seldom flies its flag in ordinary talk. Yet that talk ought to be the outward and audible sign of inward and intellectual grace. There is no virtue in slipshod disregard of the fundamental rules; yet those rules are flagrantly disregarded save on the rare occasions when one is consciously trying to heed them, or feels that one is on dress parade and is therefore called upon to act otherwise than one usually acts.

It may be erroneous to assume that English stands in a class by itself in this matter. Possibly the speakers of French, Italian, Spanish and German offend just as conspicuously as do we. Nevertheless the doubt is suggested; and the intent here is to urge that the colleges might, by more insistence, improve very appreciably the daily speech of the ordinary man and woman with pretensions of culture, placing more stress than seems ordinarily to be placed on this element. One might expect to be penalized for obvious errors in spelling; but is there similar emphasis placed on oral work ?

Not long ago, in the course of a conversation relating to the oral examination of a candidate for a doctor's degree in a famous university, one of the examiners spoke of the propensity of a candidate to say, "this here proposition," or "that there case"—apparently in sublime disregard of the fact that such expressions (proper enough in France, by the way) are not recognized as good usage in English. Was the candidate awarded his degree? Certainly. In the subject in which he specialized he was admirably qualified and his colloquialisms were not for one moment considered as material to the question, although if he had been taking a written examination and had spelled as badly as he spoke, it was admitted that he might have suffered more severely. Yet we have heard of a senior thesis written by a young woman who gained thereby sufficient credit to obtain her degree, on which the examiner's comment was that while it was an excellent thesis he thought there was hardly a line in it which did not contain at least one misspelled word.

Just how far the mere faulty mechanics of a thesis should weigh against its excellence of thought, apart from the clothing thereof, may well become the subject of serious consideration by those whose business it is to assess the attainments of candidates. Let the suggestion here suffice that scholars are judged by the outside world in some part by their ability to use, and spell, the words which body forth what is in their minds. At this moment there lies before us a newspaper item which relates that a normal school graduate in Massachusetts has won a prize for an essay entitled, "Why Smoking Is Not Good for You and I." Possibly this is due to misprinting, although in view of current circumstances that is open to grave doubt. If it is not, but is in fact the title of the prize-winning composition, it becomes the more surprising to read that this essay is very likely to be used in the schools hereafter as a document bearing on narcotics. Sound it may be on that special topic, but its regard for the elementary rules of English grammar is certainly not revealed in the title as published. It may afford a useful commentary on the reasons for defilement of the well of English, when aspiring teachers of the young wax indifferent to their personal pronouns even in prize competitions.

It is not clear as yet to what extent the colleges can go in giving weight to the spoken words of their students as counting for or against scholastic standing; but it does seem that something should be done to prevent the further pollution of the stream, by a greater insistence on respectable English, to the end that when young men graduate and go forth as accredited representatives of collegiate culture they may bear among their credentials a habit of speech for which it is not necessary to apologize. Circumstances alter cases, to be sure. One may not ask that people exchange all their ideas in stilted phrases. But surely it is not too much to expect that the holder of an A.B. degree will speak his native language without the more glaring errors, even if he has not learned to speak any other.

It may not be greatly to the credit of our educational system that very few, save those who acquired knowledge in nursery days without knowing the why and wherefore, are enabled by their training in schools and colleges to speak French and German usably; but it is certainly to the discredit of that system if any great number of Bachelors of Arts go forth into the world unappreciative of their duty toward the rudiments of their own accustomed tongue. We are taught in schools that the French, German, Italian and Spanish grammars are to be respectedand even in this undisciplined age that our own ought to be respected too—but possibly too little is done to enforce, that latter respect as a matter of our daily give-and- take. We take abundant thought for the body, wherewithal it shall be clothed, and no nation on earth is better dressed than our own. Are we sufficiently solicitous in the matter of clothing our thoughts ? It would help if the American public—the better educated part of it—outgrew the feeling that habitually correct speech is consonant only with scholastic pedantry.

The major trouble appears to be that no serious condemnation attaches to slovenly speaking. On the contrary it might almost be said that the condemna- tion, if any, attaches to nicety of speech, save on state occasions, 'by common consent. Loose constructions are in fashion for ordinary wear and one dislikes to run the risk of seeming to strut. There's the great difficulty, then—to make, something else the received fashion of educated people ; to make correct speaking a matter of ordinary use, perhaps even of unguarded instinct, instead of constant watch and ward.

In a degree this distressing situation is chargeable to the American passion for picturesque slang—a good thing overdone. No brief is here intended to be held against slang phrases which occasionally prove their worth and become phrases in good and regular standing. Now and again such expressions fill a long-felt want, vividly and adequately. Nevertheless it is not to be gainsaid that the passion is carried to gross excesses and that college men are among the worst offenders —aided and abetted by the popular song writers and the slapstick humorists of the serial cartoons, who are not assisting a great and free people to accurate utterance by popularizing "gotta" and "gonna" and "wanta". That, however, is a small part of the trouble. The great defect lies in the fact that to be scrupulous in speech is so uncommon as to seem an affectation; where as the need is to make it the regular and usual thing among people claiming to be educated men and women

We mention this he,re with some diffidence because in the main it is an educational problem rather than one pertaining directly to alumni. Yet the feeling will not down that even alumni, by their walk and conversation, might be of real assistance in promoting a more sedulous regard for the approved niceties of speech, by building up a public opinion which will react strongly against slipshod speaking in perfectly ordinary, eve,ry-day talk.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

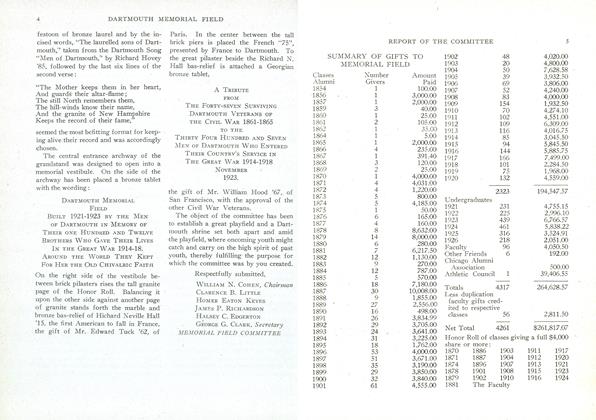

ArticleDARTMOUTH COLLEGE MEMORIAL FIELD FUND CONTRIBUTORS BY CLASSES

August 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY-SEVENTH COMMENCEMENT

August 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

August 1926 By Jesse K. penno -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1926 -

Sports

SportsTHE DISTRIBUTION OF FOOTBALL TICKETS

August 1926 By James A. Hamilton '22 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES MEET IN HANOVER

August 1926

Article

-

Article

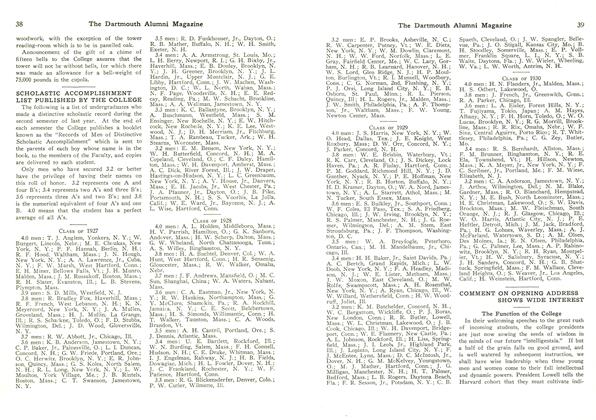

ArticleSCHOLASTIC ACCOMPLISHMENT LIST PUBLISHED BY THE COLLEGE

NOVEMBER 1927 -

Article

Article217 Rare Volumes In Gift to Library

February 1950 -

Article

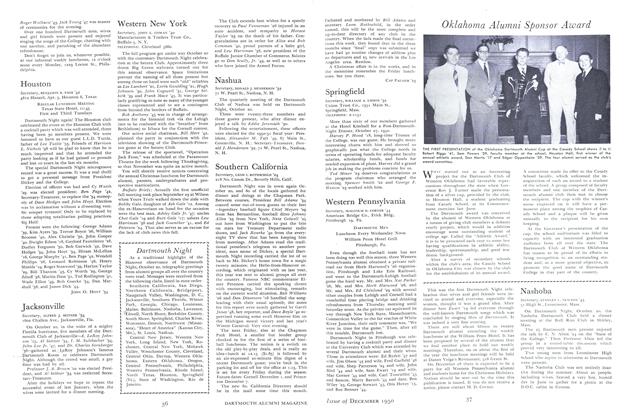

ArticleDartmouth Night

December 1950 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Article

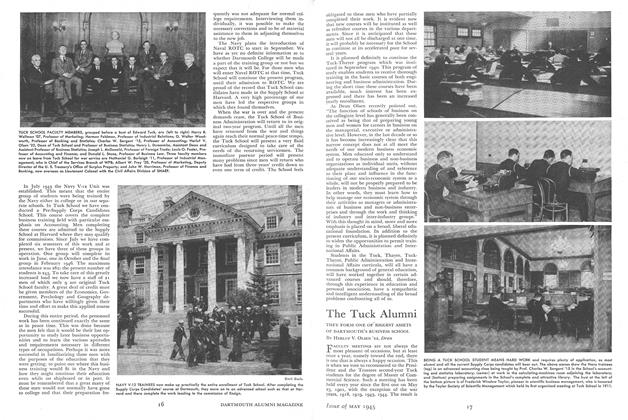

ArticleAMOS TUCK SCHOOL

May 1945 By HARRYR. WELLMAN '07 -

Article

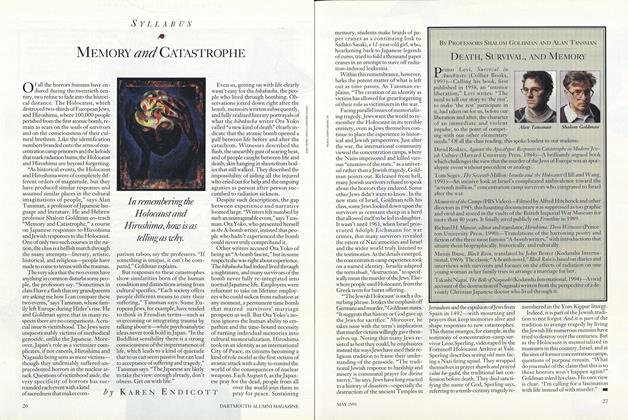

ArticleDeath, Survival, and Memory

June 1995 By PROFESSORS SHALOM GOLDMAN AND ALAN TANSMAN, JOSEPH MEHLING '69