THE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926.

JANUARY, 1927THE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926. JANUARY, 1927

Mr. President, Men of Wabash College, and other distinguished guests:

As subject matter for an address on this occasion three topics suggest themselves. First, the meaning of the ceremony; second, the attributes of a college president, and third, the function of the institution in whose honor we gather.

A distinguished scholar and administrator among my friends was invited to assume an important post in Japan. In knowledge that the conventions invited a call from him upon the Premier and in genuine desire to express his esteem and to bespeak the friendliness of the American people, he prepared a short but eloquent address.

The meeting was arranged, the appointment was kept, the appropriate speech of several paragraphs was delivered by the American visitor, whereupon the interpreter turned to the official host and deferentially uttered a single polysyllabic word. In response to this the Premier courteously bowed and the audience was over.

Returning from the palace, my friend expressed curiosity to his English secretary, in regard to the significance of the one word which had been used to interpret his entire address. The secretary, after a moment's hesitancy, said the meaning couldn't be exactly translated into English but that a near equivalent would be "Ceremonial Hokum."

In America no formal occasion from the launching of a dreadnaught to the installation of the Most Exalted Ruler in the local lodge is complete without its "Ceremonial Hokum." You, Mr. President, and I, and this distinguished audience recognize that it is true of an academic occasion of this sort.

Even so, however, the event is not to be regarded as undesirable nor indeed as without its own particular importance.

An organization of human beings can not function effectively, in the natural course of events, without some coordinating agency among multiform types of effort, some harmonizing influence among conflicting ideas of what constitutes the common purpose, some energizing stimulus upon diverse ambitions which, left to themselves, would too often become neutralized in conflict one with another.

Herein lies the function of the college administrative head, to meet these needs. If to the indispensable qualities required for these he adds sincere respect for the opinions of others, fertility of imagination, and persuasive intelligence, his associates have reason to accept his presence in their midst with such equanimity as their respective views on the merits of American college organization will allow.

Consequently, to that constituency of faculty, alumni and undergraduates which makes up a college organization it becomes important to have an opportunity to judge how the unknown quantity X of college accomplishment is to be modified by the new permutations and combinations involved in a change of administrative direction.

Such an event as this, then, is not merely "Ceremonial Hokum," nor indeed predominantly so. It is even more largely a common pledge of fealty among us all to educational idealism. It is a re-consecration m on our part to the interests of society at large for which the American college primarily stands. And, Mr. President, it is a formal acceptance of your cooperation in common endeavor for the public good.

Continuing to the second topic, Mr. President, I crave the privilege of an even more personal word with you.

More than a decade ago when I was undergoing the initiation ceremonies introducing me to the guild of American college presidents, a sagacious counsellor, in formal warning, enjoined me not to take my work too seriously, nor myself. Rightly interpreted, I have found the suggestion good, and now pass it on to you.

This is quite a different thing from advice not to hold your work of vital importance or not to hold contributions which you can make to it as potentially of major significance.

Leadership in modern days means influence, not mastery. Education is effective only when it is accepted. It gets nowhere when it is but offered. Its desirability is made manifest, therefore, by persuasion. It is but rarely helped by command.

You are entering formally, today, into an office in the American college world to which, in the course of centuries, ceremony and form in considerable degree have become attached. Beware of them!

Ceremony, as I have said, has its useful place, and form ought not to be ignored as an influence toward orderly and dignified procedure. To the extent that either ceremony or form tends to dehumanize or to make impersonal the work of a college president, however, it should be held to be anathema.

The organization of the American college is fundamentally designed to make educational advantage increasingly an influence in the lives of human beings. He who becomes oblivious to the attributes of human beings in seeking to learn the principles of educational method misses the point of his responsibility.

This, I think to have been the meaning of this warning.

Your presence here today, and these exercises, are an expression of confidence on the part of the Trustees of Wabash College that you are qualified to advance the interests of this important institution of higher learning to new position and to capitalize into new dimensions of influence and useful service the efforts and accomplishments of hosts of men who have contributed to this vital enterprise these many years.

A college is no impersonal thing. In- to its veins and arteries is poured the life blood of innumerable persons who have accepted self-sacrifice that it might live. Among such are generous benefactors who have denied themselves that to its vitality material resources might be added. There are wise counsellors and stimulating teachers who have dedicated their lives and their careers to adding their personal strength to its institutional strength. There are devoted graduates who have sustained keen interest and have given loyal support that its breadth of influence might ever be widened.

It is to no inanimate form that you pledge your loyalty today. It is to an alert and vibrant organism, filled with the breath of life, and capable, if urged, of surmounting the adjacent heights of difficulty, beyond which lie the promised lands of opportunity, wherein service may make for maximum good to men at large and wherein men individually may find greater satisfaction.

When I say not to take yourself too seriously, nor the work, I mean, moreover, that you should not allow yourself to be overpowered and benumbed by the vastness of opportunity in the field of interest to which you have committed yourself. Nor should you be weighed down by the heavy sense of obligation which of necessity will be yours. Nor should you allow yourself to become oppressed with the occasional sense of loneliness that will overcome you as, among men who of necessity can see only nearer objectives as desirable, you strive to attain goals far distant and not always sharply defined.

The penalty of those men who enter upon educational work in various capacities is that whatever may be true of other men they can allow themselves contentment with no narrow view and can feel ambition satisfied with no small accomplishment. The criterion of value by which men in many another field of activity adjudge themselves successful can never be theirs.

Into their ranks, Mr. President, you have entered after careful deliberation. Among their membership you have enrolled. Therefore, to you among these, I say, give recognition to the vast scope of the task to which you are called and take your satisfactions in the opportunity offered to make somewhat of an advance in the pursuit of great odjectives, rather than ever to allow yourself to be discouraged by the judgment of those who seek only for little things.

It is a tantalizing, elusive, but challenging opportunity to which you have pledged yourself. The past is important as bearing upon the present, and the present is important for the light it may shed on the future. But the work of the college is always fundamentally for the benefit of a tomorrow about whose circumstances we can but inadequately know.

Herein lie the difficulties of college administration. An institution tends to be stationary when it ought to be galvanized. It tends to hold back when it should go ahead. It tends to be cautious when it should be bold. The offsets to these tendencies must be provided by personal initiative and individual influence of the men who man it.

The college which is overcautious in its method or overfearful of making a mistake in its policy withers intellectually and dies spiritually even more promptly than does the college suffer grievious harm which is guilty of mistaken boldness. Progress should be unceasingly sought, though with understanding that the advantages of evolution as a working theory; over revolution, are nowhere more obvious than in the development of educational policy.

I have said sometimes that the worth while college must always be as one who dwells upon the mountain top, upon whose face first there is reflected the light of the coming day. The college function to recapitulate the past is simply that it may acquire the basis for intelligent prophecy.

In general, however, the world does not prize its prophets in their own times. The men who have seen things first and have undertaken to show these to their brother men have not in general received acclaim from their contemporaries nor have they in general been recognized as highly useful in their own times. More often gibbets, stones and fires have been their portions. These have been the price they paid for the privilege of saving their own souls or the will to advance the public good.

Yet these indisputable facts, nevertheless, may, by implication, lead us into gross error if wrongly interpreted as they may easily be interpreted by the overserious who under a sense of strain have lost their sense of proportion, or perhaps worse, their sense of humor.

Because as we look back over the ages we recognize an almost infallible instinct of a generation to stone its prophets, it does not follow that all whom a generation have stoned have had the gift of prophecy. In fact, the reverse is so overwhelmingly true that an educational institution must everlastingly be reviewing the validity of its own aspirations and of its own accomplishments that it may not, by generalization, fall into the error of assuming popularity to be a stigma or of conceiving public disapproval to be indicative of farsightedness in view and high intelligence in purpose.

When we say that a situation is serious we mean generally that it is dangerous or menacing. College administration in these days has many aspects that tend to precipitate one into this attitude towards it but it is a tragic mistake to yield to the influence of these.

Participation in college work is a task to be undertaken joyfully, in happiness at the associations it offers, in gratification at the ideals which govern it, and in elation at the range of territory yet unsubdued over which dominion may be acquired. The tears of Alexander for lack of new worlds to conquer can never be shed by the college teacher or by the college administrator.

The final measure of a man's accomplishment, herein, is not whether he has been acclaimed a hero or has been judged a worthy candidate for martyrdom. It is, rather, whether by his influence, working through his institutional affiliations and striving to realize its ideals, praiseworthy efforts of his associates are reenforced and substantiated to an extent that thereby men enrolled within the college in his time emerge from it mentally and spiritually larger than would other wise have been their lot.

I come now to my third topic which is discussion of our educational purpose. So much has been written and spoken upon this matter that little can be said that is not either review or a recapitulation. But on the contrary never can too much consideration be given to this subject.

The greatest single value in the American system of higher education is its variety of form, its diversity of method. Out of this gigantic experiment, the greatest the world has ever seen, there must come in time some knowledge of what is better in method and purpose and what is less good. For the present and long into the future we want no standardization, 110 uniformity. Technical schools, colleges of agriculture and the mechanic arts, vocational schools, schools of applied science, schools of pure science, cultural colleges, and colleges and universities in which some or all of these functions are blended, are alike important phases of the same experimental problem of how mental power may be conserved and expanded. The success of the experiment depends, of course, on each type of institution striving to realize the most from establishment of its own particular thesis.

Partly because we are discussing the matter in this distinctive college of liberal arts and partly because my own acquaintanceship is more intimate with the historic colleges of this type, I will try briefly to discuss the definition of educational purpose typical in institutions of this kind.

Education is mental enlargement. Its possibilities of development are in awakened minds. Its stages are by imitation, first; then by the effect of verbal precept and admonition; then by acquisition of knowledge through the printed word; and later by correlation of knowledge leading out towards abstract thinking.

In "Science and the Modern World," Professor Whitehead says: "Suppose we project our imagination backwards through many thousands of years, and endeavor to realize the simple mindedness of even the greatest intellects in those early societies. Abstract ideas which to us are immediately obvious must have been, for them, matters only of the most dim apprehension. For example take the question of number. We think of the number 'five' as applying to appropriate groups of any entities whatsoever to five fishes, five children, five apples, five days. Thus in considering the relations of the number 'five' to the number 'three,' we are thinking of two groups of things, one with five members and the other with three members. * * * We are merely thinking of those relationships between those two groups which are entirely independent of the individual essences of any of the members of either group. This is a very remarkable feat of abstraction; and it must have taken ages for the human race to rise to it. During a long period, groups of fishes will have been compared to each other in respect to their multiplicity, and groups of days to each other. But the first man who noticed the analogy between a group of seven fishes and a group of seven days made notable advance in the history of thought."

The ultimate purpose of the so-called cultural college is aroused thoughtful ness, that is, the cultivation and expansion of the minds of its students to the limits of their possibilities in the realms of abstract thinking. Premising its work by the cultivation of some sense of cultural values, and bulwarking it by an elementary store of indispensable knowledge, the primary interest of the college should be in the possible capacity of its men to deal with abstractions and to apply these to the solving of problems of our social adjustments in our common life.

Not all men who are accepted into membership in the college can become productive thinkers. But amongst the host who cannot, in many a one a sense of respect can be cultivated for this kind of thought, as can a sense of its proportionate worth as compared with the motivation of utilitarian thought directed to purely material ends.

Extending out beyond the results of all our scientific research and accumulation of new knowledge, out beyond our command of physical reserves and the enormous increase of power available to the human race, out beyond, indeed, but particularly because of these, lie the impending, threatening, but as yet intangible problems of social adjustment. Never was the maxim of Marcus Aurelius more to the point: "Men are created one for another: either then teach them better, or bear with them." And to this might be added the reflection of Dr. Arnold, "It is clear that in whatever it is our duty to act, these matters also it is our duty to study."

Day by day we are crowded into a smaller world, wherein the impact of individual upon individual and of group upon group is more frequent and more violent. A theory of untempered individualism makes for anarchy on the one hand, while on the other hand collectivism means standardization of opportunity, mediocrity in attainment and stupidity in environment.

Are these remote alternatives?

In our own day we have seen the attempt in one great state to establish as a working political practice a proletariat of the workers. Now we are told of the contemplation in another great state of a plan for setting up an oligarchy of the selected sons of Fascism.

Wherein but in intelligent thinking are the solutions to be found which shall restrain individual desire for the public good, on the one hand, and on the other

protect the genius or talent of the individual against the paralyzing coercion of the crowd. Wherein but in abstract reasoning are the definitions to be established as to what constitutes a service to society and as to what constitutes dis-service.

Certainly not in acceptance bodily of a mass of principles adopted for other times is maximum contribution to be made. Nor yet is it to be made in rejection en masse of practices heretofore valuable, because some no longer work. The task calls for discriminating minds acquainted on the one hand with the habit of speculative thought and having knowledge on the other hand of how the validity of evidence upon a given point is to be determined.

The greatest problem, then, of our time is how we are to adjust ourselves with the necessary promptness to the rapidly changing conditions of life. It is obviously vital that on the one hand we shall not without due consideration overthrow the structures which have been laboriously erected, while it is essential on the other hand that we shall properly utilize new principles which need to be taken into account, whether to remodel the structures already builded or to replace edifices about to be condemned.

In this connection also it is requisite that we should comprehend that social structures do not invariably have to be proved valueless before argument logically may be made for their replacement. Their real values depend not on any absolute appraisal but on their comparative worth beside the probable value of creations which might take their place. It is as though in the realm of civic improvements a highly desirable city block should be foregone to preserve the inconsequential profit of a ramshackle tenement.

The success of American industrial life more than upon any other principle has been founded on the flexibility of the American business man's mind by which he has been willing to demolish his factory, to junk his mechanical equipment, or to redevise his complicated processes of manufacture, when by so doing he could replace these more efficiently.

Yet the analogy seems to be lost upon us when one attempts to persuade us to apply the principle to social usages, political organization, educational procedures or religious objectives. Not only is an immediate attempt made to marshal public opinion to restrain action, but propaganda is immediately organized to discredit philosophical speculation. All of the forces of censorship, repression and prohibition are set in motion to preserve the theory that "whatever is" is better than anything that might conceivably be.

Hence the rise and prestige of the socalled patriotic societies in their multiform organizations, to deny the possibilities of benefit in social change; the spread and power of the Klu Klux Klan and kindred organizations to preserve the antipathies and antagonisms which blight our capacity for scientific analysis of our social state; the strength of the forces of political reaction which hold that all capacity for wisdom in political thought was exhausted in the Constitutional Convention of 1787; and the widespread vogue of the fundamentalists in religion who, viewing the great good which accrued to mankind 1900 years ago by new concepts which adapted religion to the needs of that day, nevertheless would now deny to us the right to interpret religion into terms applicable to the dire need of our own times.

It seems to be hard doctrine for many a man to accept that what Moses or Isaiah, or Testis said of religion in their respective times or what Washington or Jefferson, or Hamilton said of politics in theirs, is far less important than what these great leaders, with their courage and intelligence and idealism would respectively say today in a time so different from the times whose thoughts they so much defied and so largely moulded.

However, it is with such doctrines as these that true education must concern itself. The usefulness to society of the college will eventually be reckoned on the basis of the preparation given to men of a given era to live their lies understandingly of conditions, and serviceably to .society in decades yet before them.

This is peculiarly important in a period of such rapid change as is our own when circumstances of life and habits of thought change more in ten-year span than ofttimes before they have changed in a century. Such is the situation which seems to me to imply the necessity as never before that such institutions of higher learning as are free, to do it, such, for instance, as the liberal arts colleges, shall strive for the form of mental enlargement within their men which we call the capacity for abstract thought.

Herein lies the necessity for constant reexamination of the content of the curriculum and the technique of instruction, that subjects stimulating to the thinking of the undergraduate may be offered, and that the value of his effort may be determined by the conclusions he reaches through his own thought, rather than by the accuracy with which he reproduces the thoughts of others.

I do not ignore herein the necessity for courses requiring mental discipline, in which shall be learned by example the methods essential to productive thought and the rigorous processes of combination and elimination respectively of essential and non-essential data before a conclusion can be accepted.

Still, when all is said and done along these lines, it is the spirit of the aspiration and not the letter of the particular method which counts. It is the spirit for which I plead. Better the wrong method with the right spirit, than the right method uninspired. An attitude of confidence in the student's ability to cultivate the power of thought will have truer educational value, I believe, than any process unassociated with such an attitude.

It is one of the fallacies of commonly accepted educational theory that the interest in research and the disposition to undertake individual problems looking towards discoveries of one's own are by nature exclusively within the confines of the graduate school's work.

If the college could make its procedures more adapted to cultivating this instinct, even if not in a large number of its men and if it could give special encouragement to students who showed incipient talent for this work, the college course could be made a far more fruitful period for many an undergraduate.

The college would thereby benefit by the greater zest which would attach to much of its work. The graduate school would benefit by the increased number of men who would gain interest in continu ing the days of formal education over into the graduate school period. Most important of all, society would benefit by the increased interest in analytical thinking which would be aroused in the threequarters of the college graduates for whom the college course is the last stage of formal education, an education too frequently devised without taking into consideration at all the undergraduate's capacity, not infrequently, for cultivating an interest in purposeful and selfdevised thought.

Does someone say I overestimate the serious interest which can be aroused in undergraduates of this day or that I exaggerate in such statements the intelligent purpose which may be found in college students of this generation!

If so, I wish to say a word in defense of the youth of the American colleges.

I am becoming increasingly resentful at the extent to which the reputation of the undergraduate is offered up in academic discussion as a vicarious sacrifice for sins of omission and commission on the part of the official college or for the ineptitude of society at large.

To a correspondent who complained about certain bumpy roads, an English editor replied that they were likely to remain rough until motorists exercised more discretion in selecting the pedestrians they put down as top dressing.

Something of the same sort seems to be in the minds of many who discuss why educational progress is not smoother for institutions of higher learning. These end usually by condemnation of the undergraduates and in criticism of their qualities for undergoing the processes of the academic machine.

The only points at which I am willing to criticize this generation of college men is that they have no understanding of the imperative necessity of self discipline and that they are impervious to attempts to give them comprehension that without this neither intellectual sinew nor moral stamina can be developed except by later struggle. I admit the grave seriousness of this problem. Unless it is met and solved, all else may fail.

But whose fault is this ignorance of the value of Spartanism in self-development except the fault ;of us who are their elders ? In this country of unprecedented economic surplus where life has become easy and soft for the great mass of our population, and where rigid self-denial is little needed and little known, do we of older generations set any standards of self-discipline? In our great American delusion that to be busy is to be useful, do we exalt any idea of service? In our political philosophy of devoting exclusive attention to prosperity is there any incentive to high thinking? In our avoidance of the responsibilities of maintaining homes and in our increasing tendencies instead to establish simply lodgings, in the transition from the country residence to the city apartment, is there any influence to strengthen family ties?

There is something deeper than idle jest in the current newspaper quip that one reason the young people of today run around nights is that they are afraid to stay at home alone.

Even in our present day conception of religion, it tends to degenerate, I quote Professor Whitehead again, "into a decent formula wherewith to embellish a comfortable life," whereas, he continues later, "The worship of God is not a rule of safety, it is an adventure of the spirit, a flight after the unattainable."

The poet might have been speaking of our own generation when he declared, "Unless above himself he can Erect himself, how poor a thing is man!"

Our college youth confront a world of bewildering perplexities undreamed of in any previous generation, and face it unafraid. Unsupported by any considerable reason for respect for the generations immediately preceding them, possessed of abundant argument for doubting the validity of old loyalties which men have declared and then ignored, repelled by the interpretations of religion which pander to bigotry and intolerance, thejrevolt from the tawdriness and futility of it all.

In search for better ways they commit new follies. They defy conventions, they shock sensibilities, and too often and most serious, they inflict cruel hurt upon themselves. But in the main this generation of youth is an indomitable one, seeking to be captains of their own souls and promising to succeed. In straight for wardness, in unhypocritical honesty, in cleanness of thought and integrity of action, in aspiration and idealism, their like has not been seen before.

The question is not more logically to be asked whether the colleges can find men worthy of their advantages than it is whether this oncoming generation of youth can find colleges qualified to understand them and competent to inspire them.

Finally, though there is not time to discuss it in detail, I wish to suggest one further point. The college significance as a social group, making up a community, ought not to be lost sight of in our absorption in improving the college as a purveyor of knowledge and in attempting to develop it as a stimulus to mental power.

We can teach ethics in the class room, but knowledge of right living is acquired by contact with our fellows. There is as great difference between the two as between a diagram of how and where to throw a football for a forward pass and the execution of the same play in a contest upon the field.

Life ought to be utilized in the different opportunities it offers for the development of different attributes within ourselves. Motivation can be considered and purpose formed to best effect in detachment from others. These cannot be executed, however, except among men. Or, as Goethe has expressed it; "Talent develops itself in solitude; character in the stream of life.

No college ought to accept as valuable to its ambition a point of view among members of its faculty or within its administrative corps which ignores the significance of its undergraduate body as a "stream of life" ever in motion and ever set within different schemes of circumstance.

Moreover, since the undergraduate period for most college men is the only considerable period of their lives which will be open and will be untrammeled by the dire necessities of exacting routines about trivial things, this stream of life ought to flow largely between pleasant banks and wooded slopes whereon in turn the shining sun should make for happiness and the cool dark shadows should stir imagination and summon forth in some degree the spirit of romance native to the souls of normal youth.

The college which thinks of itself simments of instruction, and of requirements for degrees, may afford certain devices for development of talent, but it does nothing to build character, or to develop personality, or to give vitamines to mental nutrition.

The argument presented to the undergraduate ought not to be that his community life should be dehumanized and ignored as a colorless, lifeless and unprofitable thing. Rather the argument should run that college life ought to be given consequence and made colorful and vital, as too precious a possession to waste or to hold in indifference.

The college misses the whole point of its being unless with all else its influence is calculated to enhance the values of life for the individual student. Its work is barren if it conceives of itself as beingable to offer any compensation, if capacity to acquire and to enjoy these values is destroyed or even impaired. Its positive functions are to aid those who seek for themselves knowledge of what desires are worthy and how most adequately these may be realized.

Amid these none is more important than the desire to be self-resourceful and to be able to fall back upon one's own capacity for appreciation when all else palls, or fails. Perhaps this point can best be made by illustration.

Lord Dunsany in his mythical story of "The Wonderful Window" describes the longing of a young London tradesman for the spirit of romance by which he could relieve and supplement the tedium of the day's work. He tells how, at the cost of all he had, this man bought a magical window from an itinerant Oriental pedlar who had brought the treasure from Baghdad.

The marvelous window, fastened to the wall of a dingy, poorly furnished bedroom, revealed to its owner, when he looked through its panes, a sky of blazing blue, and far down beneath him, so that no sound came up from it or smoke of chimneys, a mediaeval city set with towers. Brown roofs and cobbled streets, white walls and buttresses were there. Beyond them stretched bright green fields and tiny streams. On the towers, archers lolled and beneath troubadours seemed to sing.

In short, all that the routines of the young tradesman's daily life and all that the dreary, hurrying life of the city denied him, here were found. Here, by his magical window, he sat in early morning and late at night, and dreamed, with new richness and new color in his drab life, while under his other window the motor-busses roared and newsboys screamed.

In some such way each man among us needs, in his daily life, appreciation of intangible things, such as the note of a violin string, and instinct for unattainable things, such as knowledge of God, and acquaintanceship with as much as possible of the radiant realms outside those which are the environs of his so-called practical life, if he is to realize within himself the possibilites of fullness of life. All men need their magical windows. And civilization needs peoples in which such men are far more frequently found!

By all means, we should be practical and prepare for the responsibilities of practical life. Let us, however, not deliberately prepare to live incomplete lives in which dreams, and inspired fancies, and blue skies, and cobbled streets, and ancient cities, and the songs of troubadours, and green fields, and rippling streams have no part!

We should be so exactingly practical as to insist upon securing from life its great richness which is available to those who seek it!

Let us who represent the American college strive unceasingly that through college influence life for all men may be more abundant!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHEN SHALL WE THREE MEET AGAIN

January 1927 By Professor Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment

January 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE CURRICULUM AND THE RENAISSANCE

January 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

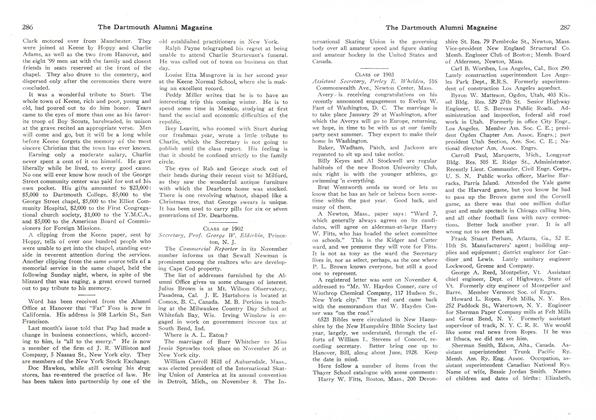

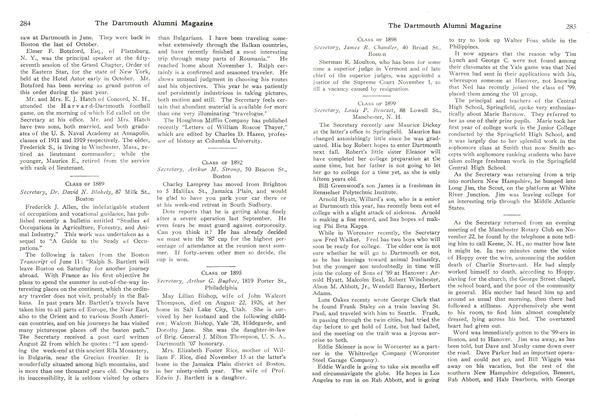

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

January 1927 By Perley E. Whclden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

January 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

January 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh