for the year 1925-26 Lektor in English at the University of Krakow.

Out of Italy there swept at the close of the Middle Ages a whirlwind that devastated the old Europe with sweetness and beauty. It traversed the venerable city of Krakow in Poland wrecking much that men had built and men had thought, but scattered in its turn the seeds of new flowers of bright colors and high fragrance that quickly sought the sun. It transformed the old dwelling places of men who had erected their houses after the solid manner of the Romans or the pointed fashion of the Goth,—it slanted up roofs and set Greek Gods on the gables, it showered ornamentation upon ornamentation upon all architectural facings, it threw bright colors of blue and red and gold along walls of churches, municipal houses, and palaces, it brought in balconied courtyards and silver fountains, it raised domes of shining crystal where before there had been but dull stone or soulless wood.

In the kingdom of men's minds it made like changes. The mighty structure of learning which the Scholastics had built up upon Aristotle and the dialectics at first stood firm against the shock. Later it crumpled like a house of cards, and the Great God Grammar fell from his hoary throne into the ruins of the old order where Duns Scotus and his disciples were already choking in cobwebs and dust. The new spirit invaded the university, entered it with an eclat and burst of rhetorical flowers, where however the last of the scholastics fought it valiantly for more than a hundred years. Meanwhile the new teaching had gotten into the university dormitories, and there men proclaimed the New Life. Storms raged about the buildings, the German, the Bohemian, the Italian quarters, were all alive with the new cult of Beauty. Humanism had replaced Dusty-ism. Poetry was read and composed all through the city. Greek was taught for the first time, and men began to read Latin for themselves and not through some pedantic scholastic.

This Fifteenth and early Sixteenth Century period was the glorious period of the University of Krakow. The city itself was a symbol of the cosmopolitanism of its teachings. For Krakow in the Fifteenth Century had become the light of eastern Europe. The Germans, the Hungarians, the Lithuanians, the Ruthenians, the Silesians, and the Bohemians, were pouring into the Studium Generale in great numbers. As the capital city of Poland it was as well the last Eastern representative city of Western Civilization, and its streets re-echoed with the glories of the merchant kings, its marts were rich with the jewels of Asia and the, spices of India, gold, diamonds, amber, silk, laces, pearls, armor, cloths, all these and thousands of others were daily offered for sale or exhibited in the ancient cloth hall or individual guilds. There were trade routes to Kiev and China, to Constantinople and Armenia, to Holland, Spain, and Rome, riches beyond human comprehension were collected within the city walls. And with this prosperity came a quick response to the new Italian teachings.

They had divided in old days the teaching of the Arts College into two groups: the trivium, or grammar, rhetoric and dialectic, and the quadrivium, or arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy. One had to finish the first group in order to attain the baccalaurea or bachelor's degree; one finished the second for the master's degree. But this teaching was narrow. It possessed unity to be true, for all these subjects were but part of Philosophy, and that philosophy was Aristotle's, or rather it was the philosophy of some commentator on Aristotle who interpreted the great writer as he saw fit. But a person with a good memory could easily attain the desired knowledge which these teachings gave. A certain I homas Murner of Strassbourg who taught for a time in Krakow, invented a system by which the dullest students could learn these subjects.

He took for example the Manual of Pierre of Spain, a horribly didactic treatise, and wrote a treatise of his own covering the work. He then took cards, about the size of ordinary playing cards and wrote upon each one the title of one chapter in the book. Under the title was a short digest of the chapter. Thus the student holding the cards in his hand could easily memorize the entire treatise. (To this day Murner should be the patron saint of tutoring and cramming agencies.) Aristotle was of course the basis of all such treatises. Rabelais, if you will remember, puts Gargantua through this same process, gaining his education by playing cards, and thus not tiring himself, or rather, combining education with recreation. Even stupid people could learn logic in this way, the manufacturer c on t en and e d, in a

single month

So in 1502 they summoned Murner before the university courts and charged him with lese majesty. The trial didn't go the way that the accusers expected however, and Murner was not only found not guilty but was given 24 florins by the court in recognition of his genius. The University of Krakow sent him a certificate of appreciation. This whole process however is quite typical of the scholastic point of view, the trial came at the end of the old period.

Memory in the new teaching was to be the chief faculty no more. "It was no more Mnemosyne but her daughters the muses who were going to guide the generation in its new evolution," says Morawski.

It was in the Fifteenth Century that the world started forward into new life. Men began to question old "truths" and to think for themselves. They put aside for the time speculation and meditation and substituted investigation. They began to invent new instruments for measuring land and sea and skies, they questioned old statements given to them by astrologers and alchemists, they refused to admit that the world was flat like the top of a box and one of them proved the contention by sailing part way round it and discovering a new land. They gave up the idea that earth has far less beauty than Heaven, and they began to find new beauties in the year, the month, and the minute. They drank the wine of old Greece instead of mulling over the cobwebs on the old bottles as the scholastics had done. They revelled in poetry and color and form. They drew Latin from the scholastic shelf and made of it a "langue internationale." They ceased to take the word of some Hipparchus, or dry Alphonsian Table, that the stars in the sky move alternately from East to West and then from West to East. They compared the results of investigations made in Italy and Vienna and Prague, and then arose one Nikolai Kopernik (Copernicus) of the year of 1491 from the Jagiellonian University of Krakow, who went to Torum and watched the skies from the balcony of his house, thereafter writing "The Revolution of the Heavenly Bodies" and establishing truth in the, face of the scholastics.

It was in the university that the life of the world was bubbling. Human thought had suddenly become as precious as men's souls and in young men thoughts were running like fire. In 1440 the University delegates at the Council of Basel came in touch with the apostles of newness from Italy; this delegation was by far the most radical that ever left Krakow. It had all the youthful attributes of idealism, it set forward ideas for reforming society, the church, and the whole world, it finally threw itself heart. and soul to the support of Felix V an "antipope." When the delegates returned to the university they displayed their prowess in the new arts at a huge meeting in the university. "Then the gracious muses, scarcely accommodated to the North, entoned their melodious songs. The council, the antipope, the envoys, were covered with flowers of speech." The New Humanism had entered the University definitely, though still informally.

From 1400 to 1450 the University walls rang with discussion of religious questions. Jerome of Prague came to Krakow in 1410 to discuss the Hussite movement and if possible to make converts. In 1413 Jerome disputed with the masters of the university in the presence of Bishop Albert Jastrzembiec. The whole Slav world was astir with religious thought. Pressure was even brought to bear on King Jagiello to make war upon the Hussites, it was pressure of a political nature undoubtedly, for the Teutonic Knights were only waiting for an opportunity to seize upon Lithuania and cut Poland off from the sea, and had Poland gone to war with Bohemia, the Teutons would have had that opportunity. And it is to be said in favor of the Poles that at a time when religious feelings were leading to war in many lands, the Poles refused to take up arms against any Western peoples simply because they disagreed with them in questions affecting faith. In 1421 the Czech deputation came to Krakow to offer the crown of Bohemia to Jagiello and to dispute Hussitism openly. In the deputation were two Englishmen Peter Payne and an unknown whose name remains only in Latin. The final dispute in 1430 took place in the Castle on the Wawel in the presence of the masters of the university, the nobles of the city, and the royal family.

Gregory of Sanok, noted prelate and virtuoso, came to Krakow after an education at Florence and Bologna where he came in touch with the new learning. The comedies of Plautus had been given high esteem in the new school, and Gregory had even composed a comedy in imitation. His influence at the University was marked. Phillip Callimachus Buonacorsi a tutor of the royal family in Krakow appeared shortly afterward and had much influence on the intellectual life of the University. He writes of Gregory: "It was he who introduced to Krakow the grace and splendor of the Latin tongue. Gregory was an enemy to Aristotle, hostile also to the Grammar. (then in vogue) of Alexander which is an inextricable labyrinth." This w-aTs" before 1450.

Valuable manuscripts began to pour into the University Library. Masters of Arts began to get uneasy in their duties of teaching dry grammar and began to take long trips in Italy and the South. Ihe students absented themselves from classes in numbers and frequented the "bourses" or pensions or dormitories in order to hear some Humanist read poetry and declaim upon Greek beauty. There was a spirit of unrest in the air, a vague impatience with steadiness, a desire to be moving: "The Renaissance bred an impassioned and almost savage impetuosity to get as much out of life as possible," quotes Morawski. Passive obedience on the part of students was a thing of the past. They had found liberty in the new cult of beauty, and the disputes and readings and battles made the University the intellectual center of one of the most interesting movements in Eastern Central Europe.

Some of them carried things a little too far however. "In all Centuries there have been vices and scandals; but Humanism introduced them into literature, glorified debauch, exalted feebleness and corruption." It is a curious thing that new movements of any kind always bring in a horde of camp followers who almost undo the good that the real pioneers of the movement have accomplished. Students took to abandoning their black robes and prowling by night over the city. Arrests began to be frequent and Morawski rather laments the calendar of the university court, because in it appear offenses that are hardly to be condoned, no matter how youthful the perpetrators may be. Most of the students carried swords or rapiers, it was an age when disputes among the laiety were settled by the sword, and advocates of the new and old schools fought in cafes and on street corners. The new culture was even preached in vile haunts amid scenes of filth and corruption, Latin verses were spouted at drunken orgies, and the townspeople were often made the targets of attack. Many a good burgomaster found of a morning his lower house windows smashed in by stones from the hands of students.

In 1491 the faculty took a hand in proceedings and ordered that henceforth all students should reside in the university buildings. It was voted also to return to "ancient regularity," to the use of punishment, prison, and excommunication. The groups that were living outside the jurisdiction now found them- selves obliged to move bag and baggage to the nearest "dormitory." Once there they found themselves under the jurisdiction of a master who in some cases made life a burden rather than a joy. But the trial records show that there was retaliation and in some cases rather severe punishment for the masters of dormitories who exceeded their rights.

The Curriculum, then, of the Humanistic period had become a matter of life, instead of a matter of mere routine study. The student might have a master in the University who favored scholasticism for example; therefore he would do the best he could for him, but would rush to the private houses for teaching under a Humanist who would give lessons in Greek or lecture upon Ovid or the Satires of Horace or even introduce the student to the mysteries of the Iliad. It was a time when men of culture learned .Latin for the very joy of it, used it and spoke it and wrote verses in it, they were not compelled to it either, but were driven forward by the great impetus of the Renaissance. The cult of Beauty was everywhere the God to be followed, investigation for one's self and experience was more than memory. When Leonard Coxe came from England the university authorities looked askance at him since he was "only a poet"; yet he delivered an oration full of flounces praising the celebrated university the title being "De Laudibus Celeberrimae Carcov. Academiae." Conrad Celtes "the laureate herald of humanism" lectured in the University in 1489, Printing had been established in 1471, but in 1491 Jean Haller set up a press that spread Humanism far and wide. "The house of the learned Agricola the Younger became a center of culture where the votaries of humanism met to hear his lectures, reading their own works and debating." Then near the beginning of the next Century Sigismund I was married to Bona Sforza of Italy, "The melodious language of Italy was heard in the streets, in some of the churches Italian songs were sung, at court the band played Italian airs." These things are recorded by Leonard Lepszy in his book "Cracow," the translation of which has been made by Professor Roman Dyboski of the University faculty.

Students then were steeped in this "new curriculum." They not only studied it. They lived it. It meant to them not only a renewed interest in study and in learning, it meant a new interest in life. The university was with them always, in the streets, in society, at court, on the field of battle. University degrees came to mean less than they had before, because students were prizing more the proficiency they had gained, than the collegiate reward for it which was the degree.

Such a record of striving toward the light as this period shows! Such enthusiasm on the part of the defenders of the old regime and the lance bearers of the new ! Learning and culture and beauty and form were as important as daily bread. But there is one feature in all this period that is most interesting to me and that is the feature of investigation, for men began then to investigate with fevered heat, to learn the causes and the nature of things. At night in the students' quarters red lights would of a sudden burst into the sky where alchemists were striving to make gold from some less precious substance. One such experiment in 1462 burned down one third the city of Krakow and carried off two university buildings. Astrologers were busy and even necromancers, some perhaps charlatans, gulling the ignorant into parting from their pennies, other sincere and honestly steadfast amidst presecution. Seeking the truth in mysterious things came Faust to Krakow, according to many writers, and there lived Twardowski, according to all. In the university library today one finds the Twardowski book with the devil's paw scrawled across it; Satan came suddenly to demand from Twardowski his presence in the court of Hell, or else to sign a compact for Twardowski's soul,—and there upon the parchment is the ugly claw, bred either of charlatan's skill or man's superstition. Both Faust and Twardowski were of a class that sought to find freedom in things of the spirit, perhaps even a release from the flesh so that the spirit might wander and adventure. Makers of almanacs were busy everywhere in these narrow streets. The first European almanac came out of Krakow with its dates, and moon risings and settings, and prophecies of good and bad alike. And even as astronomy came from and owed, its origin to astrology, so chemistry and medicine arose from alchemy and like sciences.

NOTE : Were this a history of the university and not a mere commentary upon its curriculum and the life of its students, there are certain names that would have occupied much space in the text. Bishop Peter Tomicki who died in 1535 finally "reformed the university on Renaissance lines." Jan Dlugosz (Longinus) born in 1415, died 1480, was the real historian of medieval Poland. Zbighiew Olesnicki, chancellor of the university and bishop of Krakow during the stormy period of the coming of the new learning, held the university forces together and built up the prestige of the university through the acquisition of noted professors and the addition of new buildings. He was later Cardinal. Saint Jan Kanty, one of the most lovable teachers in the history of the academy, lived in a cell in the university from 1433 to 1473. His shrine there today is the scene of a yearly celebration. He wrote almost continuously. Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (afterwards Pope Pius II) encouraged the university progress, and Canon Erasmus Ciolek (died 1522) built in the city a "magnificentissimum palatium" which became the center of an Italian and Spanish culture and played a great part in the university of the Renaissance. Many other prelates, men of learning, men of public life and fame took part in the drama that Krakow staged during this period.

References: History of the University of Krakow, Kasimir Morawski; Cracow, Leonard Lepszy, translated by Roman Dyboski; Literary History of Independent Poland, lgnace Chrzanowski.

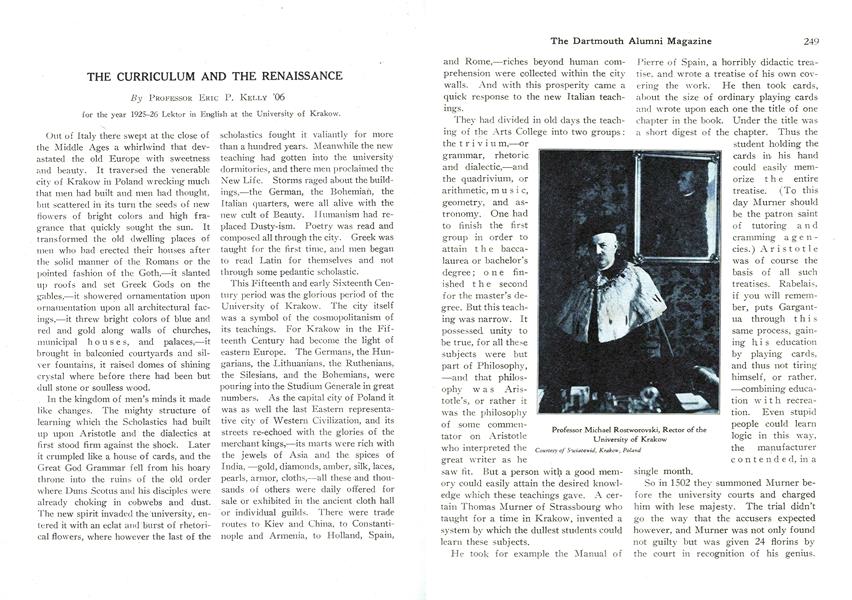

Professor Michael Rostworovski, Rector of the University of Krakow Courtesy of S-wiatowid, Krakow, Poland

Outer wall of the old library The jutting alcove accommodated a master who read aloud while the others ate

Street of the Dove, Formerly a Student Quarter The buildings are mostly of the 14th and 15th centuries. Note the buttresses for strength and defense.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926.

January 1927 -

Article

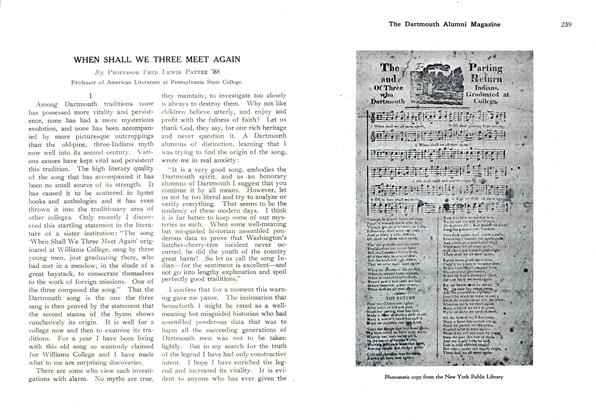

ArticleWHEN SHALL WE THREE MEET AGAIN

January 1927 By Professor Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment

January 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

January 1927 By Perley E. Whclden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

January 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

January 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

Professor Eric P. Kelly '06

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926.

January 1927 -

Article

ArticleWHEN SHALL WE THREE MEET AGAIN

January 1927 By Professor Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment

January 1927