"Lest the Old Traditions Fail"

Probably no one line in any Dartmouth song has ever aroused more discussion than the one quoted above from Dick Hovey's well known lyric. The men of Dartmouth are adjured to set a watch lest the old traditions fail surely an admirable plea, so long as the old traditions are of a sort which ought not to fail. But there comes along an age in which youth, always scornful of the wisdom of its forebears, demands that the intrinsic worth of established customs be re-assessed; and the fashionable assumption is made to appear to be that the traditions are probably absurd, qua traditions, so that the burden of proof is upon those who have a regard for them, rather than on those who raise the question of their soundness. A tradition is old it sprang up in by-gone years and has been handed down without much investigation of its merits for a long time. Therefore it is not only well to analyze it qualitatively, but also proper to assume that it is guilty unless its advocates can prove it to be innocent.

It is probably the wise course for alumni to remember that, there is something to choose, even among ancient traditions. Several of them have been outlawed and abandoned—unquestionably for the better. A tradition is not necessarily good because it is old. One feels vaguely, however, that it is also true that a tradition is not to be condemned merely for its age. If a tradition is worth keeping alive it is because it is a wholesome and salutary tradition. The more fundamental ones, fortunately, are not often called in question. Fashions may change, but one still wears clothes. It is the present purpose to stress the difference between minor fashions, which amount to extremely little, and deeper elements in the college creed which are of the essence of our faith.

Most of the argument which one reads in the turgid columns of undergraduate editorialists relates to superficialities which can hardly be rated vital and reflects the anxiety of modern youth to avoid the appearance of approving anything in the line of established order. The curt advice of the flapper addressed to her elders "be your age" is not so popular when addressed to young persons of from 18 to 20. One has a horror of being "young" and therefore natural when still green in judgment. One longs for premature maturity, and cultivates a supercilious scorn for the spontaneous ebullitions of adolescence. Thus one proves that one is not adolescent, by assuming an exacting demeanor inconsistent with that interesting period of development. Often this is creditable. Sometimes it is lacking in the power to convince.

But to get back to traditions. Every old college has them. They are what chiefly differentiate the older institutions from the younger. The rawest new college in the land may offer just as sound educational opportunities as the oldest and yet there's a subtle something that lapse of time only can supply. Traditions! Traditions good, bad and indifferent. Why talk of them as if they were presumptively things to be ashamed of, when as a matter of fact they are things for which the more recent creations in the university world would pay a pretty penny, could they only be bought?

It is not enough ground for condemnation that a tradition be meaningless. In order to merit capital punishment it should be manifestly harmful, or ignoble. One which is merely colorless, or lacking in apparent reasons for being, often has a sentimental virtue arising out of association alone. Almost any other hymn would do just as well for the purposes of the Sing Out as that old-fashioned "Amesbury," which became the traditional set-piece for that occasion in the remote days of the College. Why always sing Milton's paraphrase of the One Hundred and Thirty-Sixth Psalm at Commencement? Why wear cap and gown? Why stand up when the Star Spangled Banner is played? Why take off your hat to a lady? Well, why not? Tradition sanctions a multitude of things that one accepts readily enough without bothering whether or not they go very deep.

The Dartmouth traditions of which the poet spoke in the "Men of Dartmouth" song were such as it is well to keep from failing. One needn't bother too much about petty customs, which come and go hazing, bloody Mondays, freshman beer, football and cane rushes but one does well, just the same, not to shelve every old-established custom, petty as it may seem to modern youth, in this passionate striving to be different at any cost.

Official Changes

Recent changes in the official life of the College merit a word of comment. The vacancy on the Board of Trustees caused by the death of John King Lord last summer has been filled by the election of Dean Gray '04, for seven years dean of the Tuck School of Business Administration a man exceptionally well qualified to serve on a board which has lately suffered the loss of two men so well acquainted with the affairs of the College as were Professor Lord and Dr. Gile. Mr. Gray, as is probably well known, has had an almost constant connection with Hanover since his graduation 22 years ago. He has been an instructor in Accounting, has served as secretary of the Tuck School, and most recently has been in direct charge of its conduct as its dean. Incidental services of the highest importance, not alone to Hanover but to all the surrounding country, have been those rendered by him as head of the board of trustees of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital. Training like that should be of the very best for the particular position vacated by the death of Professor Lord. The loss of two men so intimately acquainted with the actual situation in Hanover as were he and Dr. Gile was most serious and could be made good only by choosing someone of similar opportunities for direct and sympathetic, knowledge, as well as of similarly keen and intelligent interest.

Other recent changes involve the retirement of Max Norton from the athletic organization to assume fiscal duties in the great and growing realm of the College's financial department, thus necessitating a reorganization of the athletic management. This has been met by appointing to the new position of Supervisor of Athletics Harry R. Heneage '07, in which post he will have charge of both the intercollegiate and intramural athletic activities, with control over the plant, training and equipment. He will also be a member of the faculty. The detail of the work will be entrusted to a business manager, who has not been designated at the time of this writing. These steps involve a more extensive organization of the athletic department than has existed hitherto, but the great expansion of the athletic interests and the necessity of coordinating them with the general work of the institution clearly indicate the necessity.

In Mr. Heneage it is felt that the College has commanded the services of a man of exceptional capacity and broad experience, whose interest in this side of the College activities has been both constant and intelligent a man of long experience in very considerable business affairs, and at the same time of recognized standing in the athletic realm to which his energies will henceforth be devoted. One who listens annually to the reports of the Athletic Council with their statements of the large sums of money involved will recognize even more clearly than do more casual observers what a magnitude this incidental collegiate activity has attained and how necessary it is to enlist the services of competent talent to oversee the apportionment and expenditure of such considerable amounts. The budget of Dartmouth's Athletic Council at present would do credit to a fairly prosperous industrial combination, and the responsibility is very great.

Out of Tune

The regrettable events which followed the game last fall between Harvard and Princeton seem to reveal a condition presumably transitory which really does require remedy. Experience tends to prove that when undergraduate bodies in rival colleges acquire a prejudice amounting to antipathy' whatever the cause, the one effective remedy is usually a period of abstention from contact. Experience further tends to prove that after the lapse of a few years—four at the outside, perhaps, so that an entirely new set of undergraduates may be involved relationships can be renewed with an even better spirit than obtained before the first suggestions of a breach. The instances of this are numerous enough, and at least one has been notable. It is believed that Yale and Harvard have been on far more cordial terms, athletically speaking, ever since their brief period of separation than they ever were before. The same may well become true of Princeton and Harvard.

At all events it is of the first importance that the feeling between rival colleges engaging in sports shall be generous and cordial rather than distrustful and bitter. One is never quite sure whether or not the grounds for such occasional distrusts and bitterness are justified ; but if the feeling does exist it is usually enough in itself to warrant curing the trouble by the one efficient panacea. If games cannot be played with a proper mutual feeling it is commonly wisest to suspend them until the air clears and permits them to be resumed. Dartmouth has not been entirely without experience in this matter, and may easily suffer from recurrences of it here and there. The results in the end are almost invariably a distinct improvement.

Some Bad Traditions

Among the customs of recent growth which it is felt might better be abandoned are some incident to the close of a football game notably the rather childish business of tearing up and destroying the enemy goalposts after a victory. This custom one rather expects to see perish of its own silliness—indeed there are indications that it is already trending toward the moribund. But there have been various incidents of this and kindred sorts during the season just ended, which reveal that public opinion is not yet sufficiently alert and that rather too much is still tolerated in the conduct of joyous snake-dances bent on celebrating their triumph in ways which, after all, seem rather like a throw-back to the Greek custom of erecting a trophy out of the enemy spoils, on the spot where the foe were turned back. (One is so thankful for what one recalls of one's Greek, m the case of a derived word like "trophy!")

Not often does the victorious college go the length of destroying its own property, but it does happen. The Cornellians, in a wholly natural joy over the out come of one of the most spectacular contests ever played between their college and ours, are reported to have done violence to their own goal paraphernalia which we trust and believe Dartmouth would have resisted had the scale turned the other way. If a college tears up its own equipment that is its own affair. It is quite another matter for the guest to mutilate the property of the host which is the thing that more often happens. Ordinary courtesy should operate to prevent that, even among contenders less mature and less erudite than college students.

One too easily forgets that one is a visitor in moments of excitement. If the hour of victory is really the hour of magnanimity, it might seem that the victors could afford to be ordinarily polite. Surely it is a travesty to indulge in the set forms of amenity, such as cheering the other side, and then proceed to a rough-house abolition of useful property which must later be renewed. To be sure the cost is small in money. It may be a very appreciable price in self-respect.

This goalpost business is possibly not old enough to be called a tradition yet, but the point is it ought not to become one. As for the wanton spoliation of other property—instances of this are not unknown, alas—in the quest for souvenirs, that ought to be beneath any decentminded student's contempt even when violently elated. Souvenir hunters, however, are by no means uncommon outside the colleges and are frequently of surprisingly advanced years. It is sometimes alleged to be a failing peculiar to touring Americans, although this may be open to doubt. Be that as it may, there is room for improvement among college students and even alumni with respect to the treatment of other people's belongings after a victory on the gridiron.

.Revising Football

Dr. Morton Prince in the Forum's recent symposium on football seems inclined to argue for the restoration of this sport to something like its old state before it was organized into so grandiose an affair, the advice being in its shortest form to "hand it back to the boys" so that at least they may play the game themselves and not be mere pawns in the hands of a sideline board of strategy. There is something said also about the professional coaches, of whom it seems Dr. Prince does not approve. In fine, make it a purely student affair without all these modern frills.

It is not altogether unprecedented advice; and so far as it relates to letting the teams play the game unadvised and undirected from the bench, it will find a wide measure of approval. Whether or not the public at large would relish such a change is hardly doubtful. The public wouldn't like it. It has come to look upon the game as now played as figuring very prominently among the autumnal delights. The public's ideas, however, will hardly be insisted on as paramount. Part of the trouble is that the public and the daily papers serving it have together exaggerated a student activity out of all proportion to its merit and have tended to "take it away from the boys."

Would even the students like it? One doubts this. The old fashioned game would probably seem rather a tasteless affair nowadays. There is too much allurement about the setting of a big game, the notice taken of it, the crowds, the bands, the general hurrah. These, of course, need not disappear altogether, but it is to be suspected that among the incentives operating on the critics who feel as Dr. Prince does is a wish that they might at least be minimized. The most one may say is that a great many, hopefully the majority, would prefer to see the undergraduates run their own game on the field through their own captain, and be subjected to less oversight in the matter of what plays to use, or what men to take out and put in, from strategists elsewhere. The best seat for a coach during the game is in the cheering section where some coaches will usually be found anyhow and not down among the players. One feels more doubt about banning the services of the coaches prior to the conflict. They teach, when they are proper men, much more than football tactics and therein serve a broader field than outsiders are likely to recognize. Often the coach is a stronger influence for proper collegiate activity than the academic professor. Much depends on the personality of the man.

The sage guess is that while Dr. Prince's theory is abstractly sound, it will not be adopted in full strength in the concrete because of the propensity of all concerned to get what they want. Overemphasized as football may be during the eight weeks of its season, it is a product of the times and has so much to endear it to its devotees that changes toward a simpler and less sophisticated form will come hard if they come at all. One doubts that they will come at all.

God In The Colleges

Mr. Elmer Davis, lively correspondent of the New York Herald-Tribune, has been writing of "God in the Colleges" and finds that there is still in evidence among college men an enthusiasm such as in older days went to furnish forth Crusades and other forms of militant Christianity—only in modern times it is not manifestly religious in that it is not professedly Christian. The writer sums it up by saying that "the religion now dominant among the colleges is not Christianity but college spirit," just as outside the colleges philosophers have found it not formal Christianity, but nationalism, or "the flag," or what you will. It is not formal religion, as one commonly speaks of that idea; yet it is religion in that it is a binding-together, which classically trained persons will recognize as the original meaning of the term.

Witnessing the rites incident to a send off of the football team at Hanover, Mr. Davis was more than ever impressed by the tribal character of this form of worship yet the worship of an ideal: And he remarks of it that "confronting the terrific emotional power generated by college spirit a power so intense that college faculties shrink back from it in dismayed despair—Dartmouth hopes it may be possible to harness that power and put it back of the search for truth." We gather that Mr. Davis thinks there is just as much religion abroad among us as ever there was, but that we do not always recognize it in the forms which now it takes.

After all, religion in order to be worth much, has to be heartfelt and spontaneous. One has to believe with all one's mind, and soul, and strength in the thing which one gives one's self to with a martyr's zeal. That which makes men genuinely zealous for a clean, healthy, unaffected service, subordinating self to some common cause, is in its way a religious manifestation. The consecration now so popular among men, in college and out, is sometimes very different in its appearances from that which sent the Apostles out into the world to preach the Gospel of their newly founded church to all peoples. It is not the same in its superficial guise as the zeal which brought the Pilgrim Fathers to the New England wilderness, or which motivated the famous missionary movements of older years. But Mr. Davis insists that it is in essence the same force, but operating in the channels which today make the strongest natural appeal to human emotion; and his notion that it may be "harnessed and put back of the search for truth" may well have much in it to commend. It is

something to make young men see the religion in what they and open their eyes to the fact that they are serving an ideal with a heartfelt and unpretended devotion which needs not to be whipped up by artifices, nor accelerated by a selfish desire to deserve personal reward rather than personal punishment.

As this spirit manifests itself in the colleges, it is certainly not formal or theological Christianity. In fact it has a distinctly pagan aspect at times. None the less it is the sort of thing religion is made of and all it needs is direction of a sort which will consent to use the material at hand. Harnessing this splendid enthusiasm is a rather delicate matter, but it may be done and the great religious teachers of the future will find ways and means to do it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926.

January 1927 -

Article

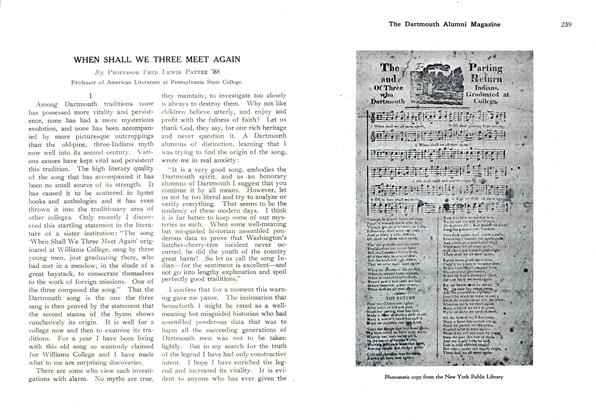

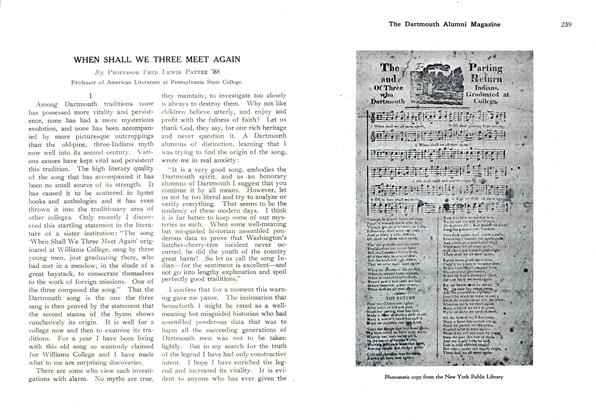

ArticleWHEN SHALL WE THREE MEET AGAIN

January 1927 By Professor Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Article

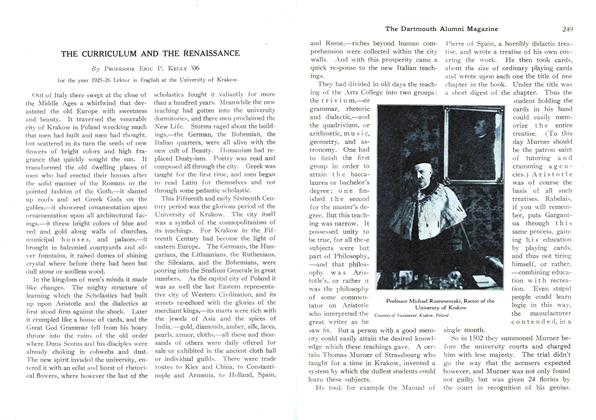

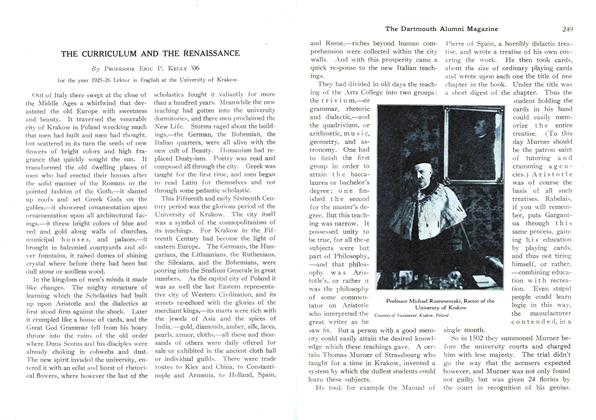

ArticleTHE CURRICULUM AND THE RENAISSANCE

January 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

January 1927 By Perley E. Whclden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

January 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

January 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

Article

-

Article

ArticleYEARS MUSICAL PROGRAM ANNOUNCED BY DEPARTMENT

August, 1923 -

Article

ArticleINN SETS NEW RECORD AS HOST TO CARNIVAL GUESTS

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

Article183rd Commencement To Take Place June 8

May 1952 -

Article

ArticleEastern Pennsylvania

June 1938 By Charles A. Stickney Jr. '21. -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

MAY 1959 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleGREEN JOTTINGS

NOVEMBER 1969 By JACK DEGANGE

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926.

January 1927 -

Article

ArticleWHEN SHALL WE THREE MEET AGAIN

January 1927 By Professor Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Article

ArticleTHE CURRICULUM AND THE RENAISSANCE

January 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06