Professor of American Literature at Pennsylvania State College.

I

Among1 Dartmouth traditions none has possessed more vitality and persist- ence, none has had a more mysterious evolution, and none has been accompan- ied by more picturesque outcroppings than the old-pine, three-Indians myth now well into its second century. Vari- ous causes have kept vital and persistent this tradition. The high literary quality of the song that has accompanied it has been no small source of its strength. It has caused it to be scattered in hymn books and anthologies and it has even thrown it into the traditionary area of other colleges. Only recently I discov- ered this startling statement in the litera- ture of a sister institution: "The song 'When Shall We Three Meet Again' orig- inated at Williams College, sung by three young men, just graduating there, who had met in a meadow, in the shade of a great haystack, to consecrate themselves to the work of foreign missions. One of the three composed the song. That the Dartmouth song is the one the three sang is then proved by the statement that the second stanza of the hymn shows conclusively its origin. It is well for a college now and then to examine its tra- ditions. For a year I have been living with this old song so wantonly claimed for Williams College and I have made what to me are surprising discoveries.

There, are some who view such investigations with alarm. No myths are true, they maintain; to investigate too closely is always to destroy them. Why not like children believe utterly, and enjoy and profit with the fulness of faith? Let us thank God, they say, for our rich heritage and never question it. A Dartmouth alumnus of distinction, learning that I was trying to find the origin of the song, wrote me in real anxiety:

"It is a very good song, embodies the Dartmouth spirit, and as an honorary alumnus of Dartmouth I suggest that you continue it by all means. However, let us not be too literal and try to analyze or verify everything. That seems to be the tendency of these modern days. I think it is far better to keep some of our mysteries as such. When some well-meaning but misguided historian assembled ponderous data to prove that Washington's hatchet-cherry-tree incident never occurred, he did the youth of the country great harm! So let us call the song Indian for the sentiment is excellent and not go into lengthy explanation and spoil perfectly good traditions."

I confess that for a moment this warning gave me pause. Ihe insinuation that henceforth I might be rated as a wellmeaning but misguided historian who had assembled ponderous data that was to harm all the succeeding generations of Dartmouth men was not to be taken lightly. But in my search for the truth of the legend I have had only constructive intent. I hope I have enriched the legend and increased its vitality. It is evident to anyone who has ever given the matter a moment's study that there are mysteries in it that never will be solved, and that no amount of research no matter how fruitful will ever destroy the real soul of it. It is one of the noblest of the Dartmouth traditions and it will always remain so. It was promulgated widely as a peculiarly Dartmouth thing perhaps during the first decade of the nineteenth century, and the song that is a part of the myth, whoever may have written it, becomes therefore the earliest distinctively localized American college song, nothing can destroy this glorious fact.

The Indian side of the legend I have not investigated. This work was so thoroughly done years ago by President Bartlett that it is useless to repeat it. From his memories of the mid-century history of the College, from replies to a circular letter sent widely to the older alumni, and from a study of the earlier records he compiled the paper published in DartmouthTraditions, a paper which threw the coldest of cold water upon the three-Indian phase of the story. No three Indians ever graduated from the College in one class, and no single Indian in his judgment ever possessed the ability to compose the song. President Smith before him had been of the same opinion: "That any Indian undergraduate, or any Indian just graduate, ever wrote so beautiful a lyric as that you inquire about, I am slow to think."

I agree fully. I have found only two Indian names mentioned in connection with the authorship, both impossible candidates. John Julian in his Dictionary of Hymnology, 1892, and several church hym- nals, have credited the authorship to Samson Occom, who died in 1792, though Julian noted the fact that it is not to be found in any collection of his hymns; and Mrs. T. D. Smith in an article for the Reformed Church Record, 1897, attributed the song to William Opes, a converted Massachusetts Indian, who for a time attended the College. But Occom surely was not the author. I find no record that he ever visited Hanover or ever saw the Old Pine. Moreover, it takes but a casual reading of the hymns known to be his to convince even the most sceptical that he was incapable, of producing a lyric of such literary excellence. As to Opes, the fact that he was born in 1798 rules him out, for he would have been but ten years of age when appeared the Port Folio version.

II

Three stanzas of the song appear to have been written by Anna Jane Vardill [Niven], who was born in London in 1781 and who died there in 1852. Her father, John Vardill, had graduated at King's College, New York, in 1774, had been elected assistant rector of Trinity church, New York, and had sailed for England to take holy orders. In June, 1774, he had been given the M.A. degree by Oxford. The outbreak of the revo- lution, however, prevented his return to America and he settled in London, where at length he became prominent as a churchman. His daughter received her education, remarkable for her times, chiefly from him. In the preface to her first volume she wrote: "A most indulgent father, in the retirement permitted by his station in the church, found amusement in familiarizing his only child with the poets of antiquity." She was remarkably precocious. Even in early childhood she wrote distinctive poetry, though she was twenty-eight before her powers were generally recognized. Fame came with suddenness. In 1809 appeared her volume "Poems and Translations from the Minor Greek Poets and Others: written chiefly between the ages of ten and sixteen by a Lady. Dedicated by Permission of her Royal Highness, the Princess Charlotte of Wales," and before the year was out it had run into three editions.

The other work of Miss Vardill we need not follow. It was distinctive. She is famous now for her "Christabell," the sequel to Coleridge's poem, so much so that the Royal Society of Literature devoted recently an entire session to her and her work. See Transactions, 1908, 2nd Series, v. 28, part 2, pp. 57-88. She is the author also of a lyric often found in the anthologies: "Behold this ruin! 'twas a skull, Once of ethereal spirit full," etc.

That she is the author of the "A Canzonet for three friends. Written at Thirteen Years of Age," which appears in her earliest volume, no one has ever disputed. The date of composition, if she is to be trusted as to her age, would be 1794. There were but three stanzas: A CANZONET FOR THREE FRIENDS.Written at Thirteen years of Age. When shall we three meet again ? When shall we three meet again ? Oft shall glowing hopes expire, Oft shall wearied love retire, Oft shall death and sorrow reign Ere we three shall meet again. Though in distant lands we sigh Parched beneath a hostile sky; Though the deep between us rolls, Friendship shall unite our souls, And in fancy's rich domain Oft shall we three meet again.

When the dreams of life are fled, When its wasted lamps are dead, When in cold oblivion's shade Beauty, power, and fame are laid, Where immortal spirts reign, There shall we three meet again.

The 1809 version, however, was not the first publication of the song. What happened to it between 1794 and 1800 we do not know, but that shortly after the latter date the English composer, William Horsley, (1774—1858), made a musical setting for the three stanzas is certain, even though the piece is hot to be found in any of his five collections of glees or in his collection of hymns and psalm tunes. That the setting was not made until after 1800 is probable for two reasons: it is not listed in the British Museum "Catalogue of Printed Music Published between 1487 and 1800", and, second, the earliest editions of the song add to the composer's name "Mus. Bac. Oxon.", a degree conferred on Horsley in 1800. The Horsley setting was evidently done sometime betime between 1800 and 1805.

The earliest edition that I have been able to find with "Music by Horsley" and "Poetry by Miss Vardell," is the Harvard Library copy printed by "Clementi & Cos., 26 Cheapside", a firm that used this particular imprint between 1803 and 1806. Two other English editions of the same song, both earlier than 1820, are to be found in the Harvard Library. The earliest copy of the Horsley setting in the Library of Congress is an edition issued by G. Graupner, 6 Franklin Street, Boston, a firm that probably had as its dates 1815 to 1820. The earliest edition that I have been able to locate in the British Museum bears this title page: "When shall we three meet again? A Favorite Ballad Sung by Madm. Caradori Allan and Miss Graddon. Written by a Lady. The Music Composed with a piano Forte Accompaniment and dedicated to Miss Stapleton. By William Horsley. Mus. Bac, Oxon. Third Edition with Improvements. London, Published by Clementi, Collard & Collard, 26 Cheapside. The firm name in this form dates from 1823. Another edition, bearing the words "Third Edition" and "arranged for three voices", bears the imprint of Cranmer, Beale & Cos., a firm that flourished for a little over a decade after 1845. All British editions of the song contain only the three original Vardill stanzas, as does also the Oliver Ditson, Boston, publication of 1845, though it describes the song as "a ballad, the poetry written by an American Indian." That the music stood high in the composer's own estimation is certain. In an album of autographs now in the possession of the Library of Congress William Horsley, under date of April 11, 1844, wrote as his contribution the first four bars of this piece.

Other settings there have been both to the original three-stanza version and to the Americanized four and fiye stanza versions, but all are of late origin. The setting in "The Christian Lyre" of 1830 is not by Horsley. In the Harvard Library there is one with melody by J. G. Drake, arranged for three voices by W. C. Peters and published in Philadelphia by George Willig, 1838.. To Samuel Webbe, the teacher of Horsley, has often been assigned the priority of composition of "When shall we three meet again?" but his song is a setting of the words in Macbeth and has no reference to the Vardill hymn. The'song also has been confounded with a hymn in Elder Knapp's Revival Melodies,. Beecher's Plymouth Collection, and other hymnals, beginning: When shall we meet again, Meet ne'er to sever? Undoubtedly there have been other settings, but owing to my defective training in music I have not attempted to trace them.

So far as I have been able to find, the earliest dated edition of the four-stanzaversion the original Vardill words with the "youthful pine" stanza added after the second stanza—is that in Dennie's Philadelphia Port Folio of August 13, 1808, with the title, "Air. By a Camerian Indian." The type must have been set by a careless compositor from a wretchedly penned manuscript copy, a copy evidently either made from dictation or hastily transcribed. Compared with later versions it is full of errors. There never was a tribe of Camerian Indians: the word was evidently an attempt to decipher "American." The fourth line of the first stanza is omitted entirely and the lines of the third stanza, here for the first time found in print with a date, are transposed from the order found in later versions: When around this youthful pine Moss shall creep and ivy twine, When our burnished locks are grey Thinn'd by many a toil-spent day; May this long-lov'd bower remain: Here may we three meet again! In all later versions the second couplet has begun the stanza. I find no other dated version of the four-stanza form until that in the "Musical Repertory. A Selection of the most Ancient and Modern Songs. Published and sold at the Hallowell book store, sign of the Bible. By Ezekiel Goodale. Augusta: Printed by Peter Edes. 1811." On page 94 is given the "Canzonet for Three Friends" with the four stanzas.

III

However, there is most fascinatingly interesting undated work from this early period. I have been able to locate five early broadsides of the song, some of them most significant: 1. The Essex Institute copy, number one by my notation, which Mr. Worthing- ton Ford judges to date from about 1812. It is headed by two exceedingly crude woodcuts, one, of what may with imagin- ation be taken for a pine and the other, of three men with cocked hats, presumably Indians. There are two poems with an elaborate explanatory heading!: "When shall we THREE meet again? Meeting of the Three Friends. The parting of the Three Indians. Composed and Sung by three Indians, who were educated at Dartmouth College, at their last interview beneath an encanting (sic) bower, whither they frequently resorted, in the midst of which grew a 'Youthful Pine'.' The Vardill song as now grown to five stanzas, the four substantially as in the Port Folio .version and a very pious fifth: There shall we forever rest, Leaning on our Saviour's breast, There shall we forever be, Gazing on the Eternal Thee; (sic) There shall we all Him adore, There shall we three part no more. In a second column appears an entirely new poem, "The Meeting of the three Friends"; one that Hezekiah Butterworth in his "Story of the Hymns" (1875) declared to be as "beautiful and touching" as the earlier song: Once more welcome dearest friends, Now at least our wandering ends, And though hope did oft depart, Oft though sorrow sped its dart, Let our griefs no more remain, Since we Three now meet again. Though remote we long have been, Many a toilsom day have seen; Tho' the burning zone we've trac'd, Or the polar Earth embrac'd We've sweets from friendship sought, Often of each other thought. Let us seek that cool retreat, Where we three oft us'd to meet; Where beneath the spreading shade, We have oft together stray'd, And where at last with anguish'd heart We did tear ourselves apart. Ah! how altered is this power, Where first we felt sweet friendship's power

How has time with ruthless blow, Laid its vigorous beauties low, Nought but this lone pine remains, And its naked arms sustains. Are we then that youthful three, Who reclin'd beneath this tree ? Then with verdant foilage crown'd, Now with moss and ivy bound, Not more alter'd is this Pine, Than our looks with wasting time. Every feature then was fair, Nor was grief depicted there, Then our sparkling eyes did glow ; Then our cheeks with health did flow, Then the lamps of life were bright, Now they spread their glimering light. Though our mortal strength decay, Though our beauties waste away; Though the lamps of life grow blear, And the frost of age appear, Yet our friendship bright shall bloom Far beyond the closing tomb.

2. The Essex Institute copy, number 2, bearing the imprint "Sold the North side of the old Market House," is practically the same as the other with the omission of the wood cuts.

3. The Harvard College copy, dating in the judgment of Mr. Ford from about 1820, and of Mr. Lane, the College Librarian, from 1800 to 1815, has running between the two poems, which are in text practically the same as the Essex Institute copies, the line, "Sold Wholesale and retail corner of Cross & Fulton Sts., Boston." To the explanation found in the Essex copies it adds the following: "The sentiments are in a high degree expressive of that simplicity, tenderness and affection which characterise the natives of our country."

4. The Library of Congress copy, practically identical, though in different style and type, has running between the two poems the line, "Sold, wholesale and retail, by L. Deming, N. 62, Hanover Street, corner of Friend Street, Boston." I have been unable to find the dates of this firm.

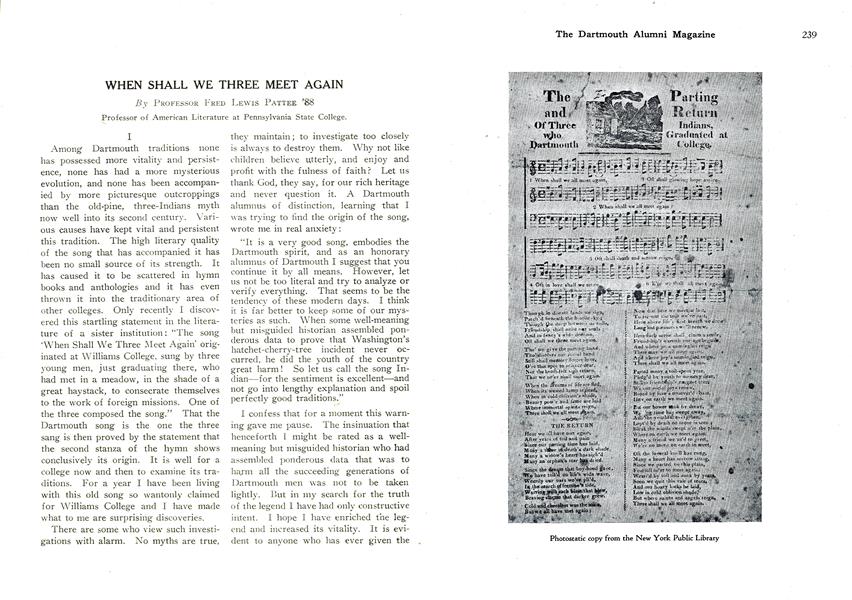

5. The New York Public Library copy has many features found in no other publication of the song. It stands by itself. At its head is a crude wood cut of a log hut, presumably Dartmouth College, with a wigwam near by. Three persons, perhaps Indians, are in sight, one at the door of each structure and one in the middle distance. The heading reads, "The Parting and Return of Three Indians, who Graduated at Dartmouth College." Then follows the music and three Vardill stanzas. The text is considerably altered. The first lines, for instance, read "all" instead of "three," though the "three" is retained at the close of the second stanza. The "youthful pine" third stanza is wholly replaced by another which, so far as I have been able to discover, is unique : Tho' we give the parting hand, Tho' disolves our social band Still shall memory linger here, O're this spot to science dear, Nor the heart-felt sigh return, That we ne'er shall meet again. The second poem, "The Return," is not at all like the corresponding poem on the other broadsides: Hear we all have met again, After years of toil and pain Since our parting time has laid, Many a three in death's dark shade, Many a widow's hearty has sigh'd Many an orphan's tear has dried. Since the dream that boy-hood gave, We have toiled on life's wide wave, Wearily our oars we've plied, In the search of fortune's tide, Warring with each blast that blew, Braving storms that darker grew.

Cold and cheerless was the main, But we all have met again; Now that here we meet at last, To recount the toils we've past, Here where life's first breath we drew Long lost pleasures we'll renew. Here each scene shall claim a smile, Friendship's warmth our age beguile, And where joys unmingled reign, There may we all meet again, And where joys unmingled reign, There shall we all meet again. Parted many a toil-spent year, Fledg'd by youth to memory dear, Still to friendship's magnet true, We our social joys renew, Bound by love's unsever'd chain, Here on earth we meet again. But our bower sunk by decay, Wasting time has swept away, And the youthful evergreen, Lopt'd by death no more is seen; Bleak the winds swept o'er the plain, Where on earth we meet again. Many a friend we us'd to greet, We're no more on earth to meet. Oft the funeral knell has rung, Many a heart has sorrow stung, Since we parted on this plain, Fearful ne'er to meet again. Weari'd by toil and sunk by years, Soon we quit this vale of tears, And our hoary locks be laid, Low in cold oblivion shade, But where saints and angels reign, There shall we all meet again.

I am inclined to date this as the latest of the five. The word, "toil-spent," and the "youthful" before "evergreen" imply that the author was familiar with the earlier third stanza which he had displaced by an original one, and the allusion to the vanished "bower" implies that he had read the early broadsides. That he believed the pine had perished

"Lopt'cl by death no more is seen" is suggestive. To this writer at least the Old Pine was no vital part of the tradition; he knew nothing of it as a still living entity to be revered, and yet he was familiar with his Hanover as is suggested by the phrase "this plain," a phrase no stranger would have used.

That the broadside is of late composition seems also to be proved from the fact that it was the copy drawn upon for publication in The American Vocalist, Boston, 1849. Here to the original statement, found in most of the broadsides, was added: "Nearly half a century afterwards they providentially met again. The recollection of bygone days drew them to the same spot, and at a meeting still more affecting they composed and sung the following." Four stanzas from "The Return" in the Public Library Broadside are then given including the one containing the lines : "And the youthful evergreen, Lopped by death no more is seen."

The "When shall we three meet again?" song seems to have reached in America the height of its popularity in the twenties. J. Willson, New York, who printed at the address given between 1816 and 1820; J. Keith, of Boston, G. Graupner, and doubtless others issued it during this decade as sheet music. Harriet Beecher Stowe remembered hearing it sung by a harness maker in Hartford in 1823. Gustavus F. Davis of Wakefield, Mass., included it in his Young Christian's Companion in 1826; Joshua Leavitt included it in his Christian Lyre in 1830. its inclusion in later collections and hymn books it is useless to follow. Bryant's collection of poetry and song, and many hymnals changed the "three" to "all," and some very recent collections like Charles A. Dana's "Household Book of Poetry," print only the Vardill three stanzas, Dana with the explanation "Anonymous eighteenth century English."

IV. If there is any foundation at all for the three-Indian story it will have to rest upon the authorship of the third stanza added to the Vardill original and of the pious fifth verse which was a later and still feebler accretion. Who added these two and what circumstance started the Indian tradition of the song's authorship we doubtless shall never know, nor shall we ever know in all probability the origin of the' broadsides and their poetry.

The song seems to have been sung freely by Dartmouth men during the first half of the nineteenth century though the knowledge of it seems to have died out during the fifties. Rev. Rudolph F. Kelker, born in 1820, wrote in 1897 to Professor J. M. Willard "In my younger days (I am now 7/) I used to sing with others the hymn alluded to in your letter, and often heard it sung and repeated." Another graduate, whose name is not given, has been quoted as saying: "The only commencement I ever attended at Dartmouth was in 1853, when I heard Choate's eulogy of Webster. On the evening of that day I was walking on the hill, for the sake of the prospect, and the pine tree was pointed out to me, which was said to be older than the college. While I was standing there, a company of four or five rather young men, evidently alumni, sang the song, in the very strain which I had learned when a child living in Connecticut." The author of "Our Familiar Songs" quotes a New Hampshire poet whose name he does not reveal: "I think there must be something in the legend, because I distinctly remember that, in 1839, one Pierce, an Indian (Cherokee) of the class of 1840, came to my home (Newport, N. H.) with a cousin of mine who was in the same class to spend a few days of his vacation, and was at my mother's house, and I remember that he sang this same song and that my younger sister learned both the words and the music, from whom I learned them, etc." Quotations might be multiplied.

Despite the English authorship of the strongest part of the song and despite the more than probability that no Indian ever had a hand in the composition of the other two stanzas, and despite the fact that the "long-loved bower" and "youthful pine" elements are pure myth, the piece is one of the most precious of the Dartmouth traditions. It is a Dartmouth song, uniquely so, taken over early by Dartmouth men, given Dartmouth color, and persistently for a century promulagted as a Dartmouth fact. That it becomes the earliest of American college songs with unique coloring makes it all the more . distinctive and all the more precious to Dartmouth men. More can be found out about its origin: this is but a crude and preliminary study, but I prophesy that nothing will ever be found that will detract from its present value as a priceless possession of Dartmouth.

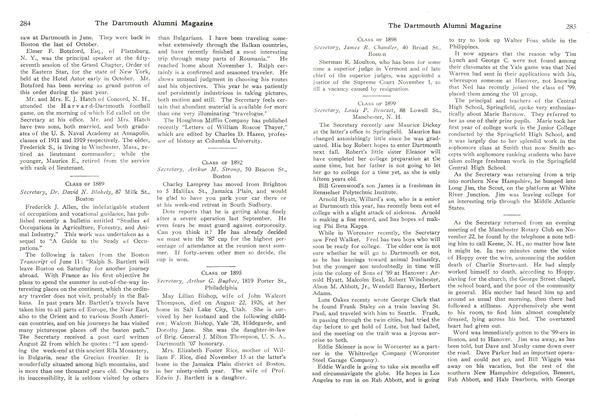

Photostatic copy from the New York Public Library

Photostatic copy of a broadside in the Essex Institute. Probably dating from 1812.

Through the Vale of Tempe

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926.

January 1927 -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment

January 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE CURRICULUM AND THE RENAISSANCE

January 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

January 1927 By Perley E. Whclden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

January 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

January 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF A COLLEGE EDUCATION: Address by President Ernest M. Hopkins at the exercises of inauguration of Louis B Hopkins as President of Wabash College, December 3, 1926.

January 1927 -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment

January 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE CURRICULUM AND THE RENAISSANCE

January 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06