Mere football dissociates itself from education, finance or controversy, but connects with selected history and discreet philosophy.

First preamble. Personally, as they say, though I know not why, I consider college football a meritorious game. The arguments have all been given, and excesses have been sufficiently condemned though not sufficiently checked. But the balance of facts is undisturbed. Those who have been long in college work will testify that the inner life of the college is better since, and because of, this game. The coordination of skill, speed, strength, intelligence and self-control is admirable. The coming together of those who "belong" to something gives power. The quality of the crowds who eagerly assemble is unsurpassed. And the excess of money which they gladly pay is wisely expended to maintain other forms of athletics which are not capable of selfsupport.

Second preamble. Football is old, so old that we may expect' yet to discover the skeleton of a cave man with a broken toe. "Rugby" football, a genus in which the ball is mainly advanced by carrying, was discovered in 1823 when young Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it. This was highly improper, and probably young Ellis was soundly cuffed by some masterful Old Brooke, but the idea took root and there is now a memorial tablet to Ellis in the wall of the Rugby playing field. Thus from the early unorganized free-for-all game we have two branches, association football or "soccer," the professional game of England which attracts a multitudinous "gate," and the Rugby or "rugger" of England modified and elaborated into the "football" of the United States. The kicking game was played in the colleges of this country very early. (My father, who entered Dartmouth in 1832, had his nose broken by some one's casual elbow.) The game was without form (but not void). You—one or one hundred—kicked the ball. And it was without rules except that the ball could not be carried; although this was in some instances modified to allow it to be balanced on the open hand or tossed up and received again on the palm.

The first organized team was brought together in 1862 by Gerritt Smith Miller from schools in and around Boston, chiefly from the Dixwell school. There were fifteen men on the team, using a round ball and playing a kicking game. During their short existence as a team they were never beaten. A tablet and a portrait of Miller were unveiled at the school in November, 1923, ex-president Eliot and Bishop Lawrence taking part in the exercises. And two years later a memorial tablet was erected on Boston Common. Princeton and Rutgers played a game November 6, 1869, at New Brunswick. It was substantially though not exactly the Association game, with twentyfive players on a side. Rutgers won this game and Princeton won the return game on the 13th. There was a match in the Rugby game in 1869, at Cambridge, between Harvard and McGill, each team playing according to its own rules. The Rugby game was played at Yale in 1874.

In 4872 it was known here in Dartmouth that there was a game in which the players carried a crazily bounding ovoid ball until someone interested in progress in an opposite direction slammed them onto the ground. But Hanover was remote from those scenes; Whole Division was good enough for exercise; and a 1ound rubber ball strongly inflated with freshman breath left nothing to be desired for this game and for class rushes. There was no flavor or taint of the modern game. Preposterous as it seems now, this health-giving sport played in the halfhour between noon and dinner and on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons was prohibited by a learned, dignified, much respected but not sportive faculty because of certain excrescences termed abuses. It was the ennobling privilege of the freshmen to furnish the ball and to be "bawled-out" on occasion of delay. And it was alleged by this tender-hearted faculty that altogether too many of these spheres suffered puncture and vanished away, thus depleting freshman purses. Later the game was licensed, with the understanding, to which this writer as chairman of a committee was a party, that President Smith, a kindly gentleman, would furnish the balls and that pointed instruments, sometimes ingeniously pro- jected from the toe of a shoe, should be barred out.

"No one is suddenly very bad," says the adage; and the approach of modern football to Dartmouth was gradual and gentle. But when the faculty took unfavorable notice it was too strong for banishment, like some other suckers from the tree of learning. In the academic year 1876-77 Trustee Parkhurst was one of those responsible for the erection of goal posts upon the Green and the practice of kicking thereat with a round rubber ball. In the spring of 1878 two teams playing the intramural game with a rubber ball gave a further impetus of which advantage was taken in the fall. Then there was a year of suspended animation which carried development over to the autumn of 1880. Are not these records to be found in the book of Bartlett and Gifford, 1893, and of Pender, 1923?

Continuous Rugby football and my own continuous memory of it date from the appearance of Clarence Howland as a freshman in the fall of 1880. Cap. Howland, an enthusiast in a cold world, early enlisted a sturdy band which he drilled with all the fidelity of a ten-thousand-a-year coach. But the lookers-on inclined to the belief that "there ain't no such animile,'' made cynical comments and even laughed at the scrambled pile of gladiators in the scrimmage.

The infant camel—to continue the figure—was forced to work for a living. The faculty showed no eagerness to adopt him, thus, Condensed from the records of the faculty.

November 8, 1880. A request for fourteen players to be absent one day at Andover was flatly denied.

September 14, 1881. A request of the Rugby football players to be absent one day to play at Cambridge was flatly denied.

September 28, 1882. To a request to be allowed to practice on the campus till 3 p. m. the reply was made that the faculty would recognize but one organization for this privilege, football or baseball, as the students might decide. (Students were presumed to be in their rooms studying.)

October 16, 1882. Niles '83 (who has recently given a $3000. scholarship to the College) was granted permission to make a statement with reference to Rugby football. What Niles' plea was is not recorded but it was a good one, and immediately after it permission was granted to play two games with Yale, one in Hanover and the other at Springfield or New Haven. This proved to be impracticable, and October 30, 1882 the concession was changed to permission to play McGill here with the omission of the afternoon recitation, and Harvard as should be arranged.

October 15, 1883. Permission was granted the Football team to be absent October 24, 25, 26; and the infant Hercules had got his nose into the tent of privilege, or the developing camel had strangled the python, as you please. Our first intercollegiate game is an event worthy of commemoration. It was played here November 16, 1881, on the afternoon of a Wednesday at that time a half holiday. It is amazing that Dartmouth should have won the first game it ever played, tied the second and, in the next season, won the third an eccentric game with McGill with thirteen men on a side (instead of eleven or fifteen) and with each team using its own scrimmage.

Naturally these successes called for an expedition to Cambridge to beat Harvard. The disastrous result of this game elicited a mortal yell from The Dartmouth and an obituary notice. But Cap. Howland was still in college, and announcement of the death of football was much exaggerated. There was one unsatisfactory game with Williams in 1883.

The Season of 1884 opened late in October with a memorable event. The Yale team came to Hanover. Probably Yale never had an eleven more capable of giving lessons in football according to the standards of the time. Even the most sanguine freshman did not expect much of a victory, but it was generally supposed that our artful dodgers would show the visitors an interesting game. And so they would if those Yale fellows had only let them play their game. They acted as though they had forgotten that President Wheelock was a Yale man. We had the ball many many times,—after Yale had kicked a goal. It was put in play by a long pass from the quarterback to a player at the end of, and a little back from, the line. He was then to run and dodge and twist and squirm past the opposing line and make a touchdown, a play that was very effective against the second eleven. It would have worked here too if the Yale men had not annoyed the lonesome performer by getting in the way. He 'could do little more than squeak out "down"—a custom of the time—from under seven or eight hundred weight of Yale beef. The visitors romped and frolicked over the Green without intentionally mutilating any of our men, and ran up a marvelous score in touchdowns and goals. Modern mathematicians have calculated it as the equivalent of 113 to 0. Never was a better demonstration of the value of coordinated play, for our men were not inferior in weight and strength. This event, natural as it seems to us, was grievous at the time, and the remaining games of the season were not encouraging. The impetus of the start was apparently exhausted and there was no schedule in 1885. In 1886 interest was renewed; the game gathered strength and started on the series which has only been interrupted by the peculiar conditions of the S. A. T. C. in 1918.

To those who are sad over the attention now given to athletics it may be said that it is far less than in the elation and depression caused by those games in the eighties. Perhaps the answer is that so much athletic business is going on at present that no one, unless engaged in it, pays serious or lasting attention. Certain it is that bells do not ring, fires do not blaze, members of the faculty are not called from their beds to make speeches as of yore.

If some sagacious judge could select an All-Dartmouth eleven from those lads of the eighties and give it the training of today it would be fast enough for any company in which it might be placed.

Time passed with slow cumulative gains. In twenty years Dartmouth won or tied seventy-one games and lost fiftyone. But successes were with teams of the second order or those less redoubtable. Not a point had been scored from any of those elevens which, decorated by the sport writers with the quality of Bigness, did not refuse the proffered crown. There were abundant reasons,—natural slow development, less numbers to choose from, the fact that after 1894 Dartmouth used only undergraduates even against university teams, foreign coaches not displaced till 1900, and an inferiority complex. The teams went up against Bigness always on its own grounds, expecting to lose as a matter of course but to gather valuable experience and to put money in the athletic purse. Harvard was always the test, the megalometer, and the scores had gradually been suggesting to the sanguine a coming day of real competition. In 1901, the second year of alumni coaching Dartmouth scored 12 to Harvard's 27; the next year 6 to Harvard's 16; then in 1903 11 to Harvard's 0. And since, although Harvard has a slight majority of games it may fairly be said that every Harvard-Dartmouth game is uncertain until it has been played. Harvard has been an esteemed teacher and usually an example of fine sportsmanship.

As I have followed football from its beginning here I have seen an amazing improvement in the game itself. Exactness of conditions, protection of the players from injury have advanced so far as to make the earliest games seem by contrast lawless rough-and-tumbles. Our first games were played in the south-east corner of the Green where there is a visible difference in level. At first the ground was not striped into a gridiron, and when the question of distancegained arose the referee could only place his heel where he thought the ball started and pace off the distance, to the great and unconcealed dissatisfaction of one side or the other. There were of course no linesmen. There was no official whose business it was to detect and penalize fouls; the referee caught them if he could and dared. But he was one, with other jobs, and they were twenty-two. And there were plenty of intentional fouls. O, yes there were. I know who pulled who's nose that time. I know who carries a scar to this day from an unprovoked, unexpected, ruffianly blow from another's fist. I witnessed the unfortunate incident in the Harvard-Yale game of 1894 which for a time alienated those high-powered teams; it does not matter now whether the occasion was brutality or unjust suspicion of brutality. It is evidence that the spirit of this sport was not as wholesome thirty years ago as it is now. The watch that kept the time was frequently in the hands of some bystander who was always suspected of juggling the returns. Not infrequently the game was allowed to run into the dark and perhaps the referee would light a match to see where the ball was and who had it. In very early times the single and inexpensive official was some amiable hanger-on who had no experience in the game and great awe of the sweaty, excited heavy-weights who encompassed him with conflicting claims. It is one of the joys of the modern game to see a hard-bitten officer of the law, football law, force his way to the heart of a struggling group, disentangle them, push them out of the way, and give judgment. The stranger should see what nice boys they are when they are washed up and dressed. Like the rest of the world they will stand any amount of good government. from the proper officers, but lacking that they are quite self-reliant.

The stalwart collegians who made up these earlier football teams were undoubtedly as amiable and peaceably disposed as their sons and grandsons, but the rules were insufficient and poorly administered. There was an atmosphere of distrust, and floating rumors of sinister designs; some valuable player was to be "laid out" early in the game. And sometimes he was, too. Players had not at that time acquired the self-control and restraint which is one of the admirable disciplines of the game; and spectators, to whom it was a good deal supposed that coaches, and especially certain coaches, taught their pupils sly methods of inflicting injuries or of irritating opponents. As I look over the list of our coaches I should not like to make this charge against any of them, but I would not "put it past" some of them to have given instruction how to meet such aggressions. I have heard players criticised for playing too honest a game,—long ago.

In 1893 there was a loud attack of a curiosity, had not learned that though rough in personal contacts it was a game and not a fight.

With aggressions there were retaliations and some deplorable episodes which, seized upon as characteristic of the game, brought it into bad repute. Now and then some scurvy fellow got into the game and after he had done an evil deed upon an opponent's person was withdrawn from the field lest he get his own back with interest, It was commonly upon the game based mainly upon its dangers. This attack caused Walter Camp to gather material, statistics as far as possible, and opinions, from those who were in position to know, which he published in a book of over 200 pages, "Football Facts and Figures," in 1894. The game was warmly endorsed, but not unanimously in the condition in which it was then. Some of the objections would hold as soundly against baseball, swimming, coasting, polo, in fact all the sports which give full scope to a young man's strength, skill and daring. From a few it might be inferred that the ideal manly sport was sitting in a rocking chair and playing checkers. There was too much "safety first." Safety first is right enough in the case of others, but not always applicable to one's self. As one looks about a college and considers how we are surrounded by sinewy and selfpossessed youth some of whom would meet any possible emergency, one reflects that the element of risk is inseparable from full development, physical or moral.

But some of these adverse criticisms were wise, and happily a watchful Rules Committee has made steady progress in smoothing away points of danger. Without substantial change in the game, except by the introduction of the forward pass, they have eliminated many causes for accidental injury and opportunities for brutality. The opposing players in the line of scrimmage have been slightly separated.. "Hurdling," jumping] over or into a struggling mass with heels of the heavy boots striking where they might has been forbidden. A player may try for a fair catch with his arms up in the air and his body thus unprotected without being tackled, if he chooses to give a signal. Piling on to a man who is down, a custom dangerous at best from mere weight, and at worst the occasion of many injured ankles and knees, is prohibited along with the crawling which gave a certain occasion for suppressing him with weight of numbers. The mass play and the flying wedge, a juggernaut stopped by prostration before it, is gone.

It is well known that a player who cannot keep his temper is best placed on the side lines. A personal encounter on the field in hot blood, or the spectacle of one player jumping on another with intent to injure would be intolerable. Due to the care in training and the authority given to physical directors a football crowd is not likely to see a player, dazed by a blow on the head but refusing to leave the field, run half the length of the field and triumphantly make a touchdown back of his own goal. As for fatalities, the number recorded in a whole season in fortyeight states is only a few more than the average number in one week in Massachusetts alone from automobiles. When one considers the vast number playing match games in high schools, academies and colleges,—is it too many to estimate 100,000 in one week?—besides practice games, the minor injuries, bruises and sprains, do not seem cause for alarm.

Our coaching systems naturally divide into three, the household system, the foreign-born system, and that of the returned native son. The household system prevailed during the first thirteen years and in that time two captains, Howland and Odlin, each had charge of the team for four years beginning as freshmen ! and one year no team was organized. These men were unusually well qualified to train a team, but it is probable that they sacrificed some of their own playing, and there would naturally be a greater tendency to repetition than to invention. Much might be said for this system; but to be coach, captain, player and to bother with "those studies" spreads a good man out pretty thin. For the next seven years we hired our coaches from other institutions, only two, one of them for five successive years. Then we changed, and beginning with the season of 1900 our coaches were our own graduates and have been ever since. There was definite progress in each of the three periods, but it was only in 1901 that we gave good evidence that we were moving into the superior class, the Big something. The events of recent years seem to justify a little modest selfappreciation.

The requirement of a high degree of individual skill in a football player has been strangely slow in developing. Perhaps attention has been too closely directed to weight and coordination. Consider the qualifications of a good baseball player. It is required of any player aspiring to excellence that he shall judge and catch a ball at any distance, throw accurately 300 feet or farther, handle a _ very swift ball in the air or on the ground, bat safely one-third of the times at the bat, more or less, run swiftly and wisely, slide to a base, make instantaneous decisions followed by action, have special fitness for someone position as pitcher, catcher, baseman or fielder, and subject himself to the general good. In football for a long time the essentials were weight, or speed with as much weight as possible. Ihe candidate for the team was given ludicrously scanty lessons in tackling, permitted to flop down on a rolling ball a few times, told that there was no greater misdemeanor than to drop the ball when he was thrown, given some opportunity to use his strength in blocking and interfering, made to learn the evolutions of a secret code of numbers, and told to go ahead and play the game. But accurate throwing, sure catching, passing the ball backwards, punting, drop-kicking, placekicking were special accomplishments, and a team was often seriously weakened by the loss of one specialist. In fact only recently has the football player begun to be a man of all-round skill. Long accurate passing and catching still cause surprise pleasurable or painful according to the side of the field from which they are seen. And seldom does one see clever passing backward on the run which is a feature of the English game.

To answer a recent outcry that the game is not a source- of pleasure to the players would lead into the realm of controversy. A referendum carried out by one of the Boston papers last fall seems to throw the burden of proof the other way.

Even if it does arouse an opposite opinion I venture to state the belief that the practice of making a football squad report at the college two or three weeks before the fall opening is wholly bad for everything except the condition of the players. Of course that is its purpose and the custom could only be stopped by general agreement.

Football is not a one-man game. Coordination is one of its most attractive features. Every man in every play. This year the gullible public has been led astray by the exploitation of one player, very good but matched, I am told, by a dozen or fifteen in the fall crop. Crafty promotors saw their opportunity and offered him a small fortune and it is not surprising that he yielded to their solicitations. It requires eleven players, all busy, to bring off a football combination; and the man who ambles along showily in the open with the ball against his ribs is absolutely dependent upon the other ten to give him the ball, to open holes in the line, to hold off the charging opponents, and to interfere for him on his way. College teams play their several parts willingly and their shares in the play are appreciated by the knowing spectators. Whether eleven hired men will allow one of their number to get most of the cash and all of the credit remains to be seen. There are indications that the rocket's red glare is fading to a stick already.

It is true that professional football draws enormous crowds in England. But the game is soccer which demands more even skill in the players, does not make one or two players especially conspicuous merely because of their position, and, not being interrupted by scrimmages as ours is, gives swiftly changing and exciting crises.

From the season of 1925 has arisen a wave, an uneven wave, of dissatisfaction. Too much football! Too much talk about football! Too much body too little brains in the colleges! Too many columns in the daily papers and too much scattered cash. It is pleasing to observe the prompt response to these reasonable criticisms by announced elevation of admission price to some of the more attractive games. Thus the enthusiastic and over-excitable public will be calmed and those to whom four or five dollars to witness a mere game is an extravagance will be excluded, and by reason of the empty seats in the circus maximus the waning popularity of bodily prowess will be demonstrated and the attention of sport writers diverted to feats of the intellect.

The First Rugby Team, 1881 Standing, W. V. Towle '85, H. A. Drew '83, C. R. Webster '82. Seated C. F. Mathewson '82, J. W. Flint '84, F. H. Nettleton '84, C. Howland '84, F. L. Coombs '83, J. P. Brooks '85, C. H. Brown '83. Reclining, C. W. Oakes '83, E. B. Condon '82.

A Big Game on Alumni Field

AlumnAlumni Oval in the Nineties

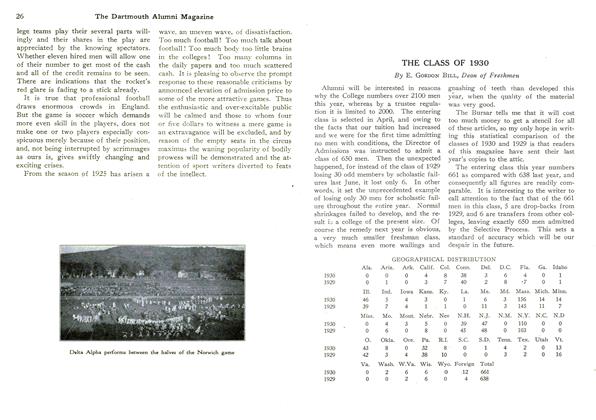

Delta Alpha performs between the halves of the Norwich game

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

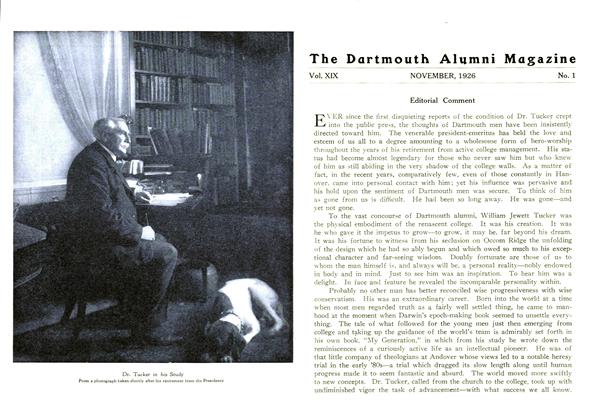

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1926 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1926 By Prof. Nathaniel G. -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1930

November 1926 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1926 By Ralph Sanborn -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1915

November 1926 By W. Dale Barker

Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

Article"WHAT EVERY PROFESSOR OF SIXTY SHOULD KNOW"

January, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE OLD SONGS

April, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleSCRAPS OF PAPER

December, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY MEETING

DECEMBER 1927 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72