DARTMOUTH UNDER THE CURRICULUM OF 1796-1819 I

Professor of History

The biographies of Webster are inadequate and misleading in their stories of his undergraduate life. In the case of Choate, there has been a dimness of picture unworthy of so extraordinary a combination of finest scholarship and extraordinary power as an advocate.

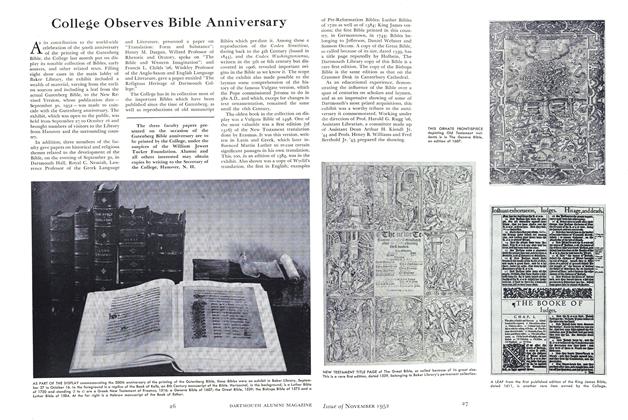

New evidence as to the college career of these two life-long friends has come to light in a dozen manuscript sources: the curriculum under which both were educated; Webster's college and town bills; library records; six college letters of Webster, Rufus Choate, and his brother Washington; Choate's entrance certificate ; Dr. Upham's Personal Reminiscences of Choate; and the undergraduate compositions of Webster's classmate Loveland (1801), and Asa Hazen (1812). There have also become available since Professor Richardson's scholarly and memorable address at the Webster Centennial, 1901, new contemporary evidence in print:—in Vantyne's Letters of Webster, and the National Edition of Webster's Writings; the autobiographies of Judah Dana (1793) and John Ball (1820) ; three diaries,—of Reverend William Bentley for 1793, Dr. Horatio Newhall, 1819, and William Smith, 1822; and letters in the Life of Dr. Lyman Spaulding, Lecturer in Chemistry, 1798-1800. With this new material and a reexamination of the other contemporary testimony, Webster's autobiography, his undergraduate writings, the records of Phi Beta Kappa, United Fraternity, Social Friends, and the letters and personal reminiscences of the two men and more than a score of their contemporaries, there is justification for an attempt to reconstruct, on first hand evidence, the life of these men and their college under the old curriculum, from 1797 when Webster entered until 1819 when Choate graduated.

That curriculum contained in the "Laws to be observed by the members of Dartmouth College," enacted by the Trustees February 9, 1796, covered: admission ; curriculum; vacations and hours for recreation; boarding, lodging, etc.; expenses and bills ; "exhibitions;" fines ; library rules. It was essentially a joint action of faculty and trustees; for all the teaching force save the tutor were Trustees. Nor was it the act of ministers. The President and the majority of the Trustees were laymen, men of affairs, prominent in public service. Five had experience in teaching or preparing college students. Six were graduates of Yale or Princeton; only two of Dartmouth. From this representative and liberal board came a timely and fruitful educational program, especially interesting in comparison with the selective process and the new curriculum requirements of today.

The admission requirements of 1796-1819 demanded: evidence of "good moral character;" an examination to test the requirement that candidates "be versed in Virgil, Cicero's Select Orations, the Greek Testament, be able accurately to translate English into Latin and also understand the fundimental (sic) rules of arithmetic;" a bond of $300 for payment of college bills.

We can see the fifteen-year old Freshman Webster, "Black Dan," of swarthy skin, spare of frame, thin-faced, with prominent cheekbones, and piercing black eyes—"full, steady, large, and searching" "peering out under dark overhanging brows" and "broad, intellectual forehead," ushered into the room in the tavern where other candidates were gathered that "we might brush our clothes and make ready for the examination." "He had an independent air and was rather careless in his dress and appearance, but showed an intelligent look," wrote his room-mate Bingham. The tavern of 1797, where Webster spent his first night in college, later the home of Squire Olcott and Dr. Leeds, still looks out upon the campus between the white church and Webster Hall.

For examination in the four subjects (Greek, Latin, English, and Arithmetic) the candidate went in turn to each of the four members of the faculty. The last examiner then "directed me," says Freshman Smith's Diary of 1822, "to call at the President's at two o'clock at which time and place I should receive my destiny I called where I found the four Sages seated in Majesty—after I was seated the President informed me that I was admitted a Student of Dartmouth College."

The system combined the advantages of school certificate and college examination, in a selective process which attracted a striking proportion of men of challenge of an examination. One cannot resist this query. Would a like combination in the selective process of today (adding to the school certificate some test of intellectual training and capacity by the college before admission) tend to eliminate some of the too many socially ambitious, going to college, but never through college?

The "certificate" is illustrated by the recently discovered recommendation of Rufus Choate by his teacher, James Adams (1813). It not merely certifies "good moral character," and scholarship in school; it also recommends Choate for examination by the men who were to teach him in college.

"Hampton, (N. H.) August 4, 1815.

"Hon'd Sir,

"I have the pleasure of recommending the bearer, Mr. Rufus Choate of Ipswich, Mass., to you for examination for a standing in the freshman class. He has read his preparatory classics, Virgil, Cicero's orations, & Greek testament,—under my care; and I think that he hasstudied them thoroughly. But of this you will be better convinced when you have learned it from himself, and I doubt not but, in a very short time he will give you evidence of it to your satisfaction.

"While with pleasure and confidence I recommend him as a scholar, with: no less of either do I assure you of the correctness of his morals. He is free from any of those vices or bad habits, which injure the happiness of society, or would disturb the peace of the Institution. His moral character so far as I have beenable to learn, is irreproachable. With sentiments of esteem, I am "Hond Sir, your humble servt. "James Adams. Hon. John Wheelock, L.L. D."

The curriculum from 1796 to 1819 under which . Webster and Choate were educated is thus stated in the Laws of 1796.

"It shall be the duty of the student to study the languages, sciences & arts at the college in the following order, viz: The Freshmen, the Latin and Greek classics, Arithmetic, English Grammar, Rhetoric & the Elements of Criticism. The Sophimores (sic) Latin, and Greek classics, Logic, Arithmetic, Geography, Geometry, Trigonometry, Algebra, Conic Sections, Surveying, mensuration of heights and distances & the Belles Lettres.—The Juniors the Latin and Greek Classics, Geometry, Natural and Moral Philosophhy, Astronomy.—The Seniors Metaphysics, Theology & Natural and Politic Law.—The study of Hebrew and other oriental languages as also of the French languages is recommended to the students.—All the classes shall attend to composition and speaking as the authority may direct." rotation shall declaim before the officers in the chapel on every Wednes "And on the first Wednesday in every month the members of the Senior class shall hold forensic disputation in the chapel immediately after declamations. At these exercises all students are required to be present."

Haddock, Professor of Rhetoric, reported in 1829 he examined 1,472 compositions, heard 124 dissertations and declamations, and 50 performances for "exhibition" and Commencement. This meant over ten "performances" of some sort for each undergraduate annually, and nearly as many daily for the unfortunate professor. This evidence is of double interest because it indicates the functions of a brilliant teacher, Charles B. Haddock, Choate's fellow-student and fellow-member of the faculty; secondly because Haddock had just persuaded his uncle, Daniel Webster, to come and talk "to your boys at Hanover," and aid in developing keener interest in writing and speaking. In a letter commending Haddock's ork, Webster suggests characteristics of undergraduate life common to both 1825 and 1927.

"The tendencies of a college life are doubtless drowsy ; and you deserve there- fore the more praise for showing signs of life. It is not always that a pulsation manifests itself in those sons of leisure, who having no absolute engagements for the future, refer to the blank of tomorrow whatever might have made today something better than a blank."

Forty-five subjects for "composition and speaking" suggested by the resourceful Professor Haddock for Freshmen Compositions are recorded in the Commonplace Book of William Smith: "the pleasures and pains of the student"discovery of Herculaneum"whether extensiveness of territory be favourable to preservation of a republican government "the pursuit of fame"reflection, reading and observation as affording knowledge of human nature"are the natural abilities of the sexes equal?"

The fourteen Sophomore compositions of Webster's classmate Loveland upon "Detraction, Selfishness, Avarice, Friendship, Mankind framed for society, Imperfection the lot of man, Reason productive of happiness, Liability of man to err, Systems of government never long endure, French Revolution's abolition of religion, Do to others as you would they should do to you, Malo periculosam libertatem quant quietum servitium," show the vague generalizations inherent in the subjects and in Sophomore writers; but also manifest orderly arrangement and felicitous phrasing. In addition to such biweekly, one-page compositions, Love-land and Webster would have prepared disputations or orations. The fifty-three compositions or orations of Asa Hazen (1812) show his growing power in successive years. His Freshman composition, "Man is never content with his present conditions," was so true that he logically demonstrated it by writing much better Sophomore and Junior compositions on "Man is continually changing the object of his desiresand "The passions of mankind are continually changing." Sentiments of his day and section on the eve of the Hartford Convention are reflected in his Junior debate arguing that the separation of the United States would promote the interests of mankind, because sectional animosities and clashings of interests make it "better to divide now than after a civil war." Loveland's Sophomore compositions contained on an average about two hundred and fifty words; Hazen's compositions about five hundred, and his debates about fifteen hundred words. There are indications of instructor's corrections and student's rewriting.

Professor Colby's careful research in his valuable account of "Legal and Political Studies in Dartmouth College, 1796-1896" led him to conclude that the Junior study, "Natural and Moral Philosophy, " was probably based in 1796 (as in 1816) on Paley's Moral and PoliticalPhilosophy; and the Senior Study, "Natural and Political Law," on Burlamaqui's Principles of Natural and Political Law, first published in Geneva in 1747. In confirmation of Professor Colby's conclusion as to Burlamaqui, is Webster's letter two weeks after graduation: "I expect next to review Burlamaqui and Montesquieu." Burlamaqui's NaturalLaw, one of the staple books of that day (a favorite of John Adams and Alexander Hamilton) had appeared in seven editions in English before 1800, and was on sale at the "Hanover Bookstore" in 1801. Four copies had been acquired by the college library by 1796. It was also in duplicate in the first printed library catalogues of the Social Friends, 1810, and United Fraternity, 1812. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (1826), like Webster, wrote: "I had looked through Burlamaqui at College." At Harvard Burlamaqui and Paley were text-books required in the Laws of 1816.

The curriculum and nine of the textbooks in Choate's undergraduate days are definitely known through the report of the New Hampshire Legislative Committee in 1816 based upon a visit to Hanover.

"For the Freshman Class. Cicero de Oratore, Graeca Majora, Livy, English Grammar, Arithmetic, Rhetoric, Composition and Speaking.

The first three of these have been introduced at different times since the year 1806, instead of Virgil, Cicero's Orations, and the Greek Testament, now required before admission to college. For the Sophomore Class. Horace, Graeca Majora, Geography, Algebra, Euclid four books (introduced since 1800), Mensuration, Trigonometry, Surveying, Navigation, Logic, Composition and Speaking.

Horace was taken from the Junior and introduced to the Sophomore Class in place of Cicero de Oratore. Graeca Majora has been recently substituted for Horace. For the Junior Class. Graeca Majora, Tacitus (introduced in place of Horace), Euclid, Sth and 6th books. Conic Sections, Chemistry (introduced in 1813), Kaime's elements of criticism, Paley's moral Philosophy, Paley's natural Theology, Alison on Taste, Enfield's Philosophy and Astronomy, Composition and Speaking. For the Senior Class. Locke on Human Understanding, Edwards on the Will, Stewart's Philosophy of the Mind (both volumes) Burlamaqui on Natural and Politic Law, reviewing of the Greek and Latin languages (introduced since 1804), and Composition.

"The three lower classes have ordinarily three exercises in a day; in these classes much more attention is paid to the study of composition than formerly."

Copies of fifteen of these text-books (practically all that can be identified, save Enfield's Philosophy) remained in Choate's library at his death forty years after graduation.

Webster's curriculum was substantially that of Choate, the few changes by Choate's time consisting mainly in the strengthening of the classics and the addition of navigation and chemistry. With a possible margin of error, especially as to text-books, the following is a reconstruction of the curriculum under which Webster was educated. It is based upon the Laws of 1796; the Legislative Report of 1816 (with due attention to the changes there indicated as having taken place since 1800) ; library records; Webster's and WhefelocWs letters.

Freshman Year.

Virgil, Cicero's Orations, Greek Testament, Arithmetic, English Grammar, Rhetoric, Composition and Speaking.

Webster speaks of reading Cicero Freshman year. Sophomore Year.

Cicero de Oratore, Graeca Majora, Geography, Arithmetic, Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, Conic Sections, Surveying, Mensuration of heights and distances, the Belles Lettres, Logic, Composition and Speaking.

Webster recalled with especial interest Sophomore work in "Geography, Logic, Mathematics." "Belles Lettres" was probably covered by Kaime's Elements of Criticism, and Alison's Essay on the Nature of Principles of Taste, used by Asa Hazen of the class of 1812, and required in 1816. Kaime's Elements of Criticism is among prerequsities for entering Junior year (in Wheelock's letter of 1800 to Lyman Spaulding) beside "English language, Vir Gil, Tully's Orations, Greek Testament, one or two books of Homer, Arithmetic, Trigonometry, Geography, Logic, Tully, de Oratore."Junior Year.

Horace; Graeca Majora; Geometry, Paley's Moral and Political Philosophy; Paley's Natural Theology; Composition and Speaking; Natural Philosophy and Astronomy, presumably as in 1816, Enfield's Institutes of NaturalPhilosophy, (I) Physics, (II) Astronomy, of which the second edition was published in 1799. Senior Year.

The 1796 provision for "Metaphysics, Theology and Natural Law" apparently was met, as in 1816, by "Locke on Human Understanding, Edwards on the Will, Stewart's Philosophy of the Mind, Burlamaqui on Natural and Political Law." In his Senior year, Webster records his appreciation of Locke and his reading with great admiration Stewart's Philosophy. All four were certainly the text-books in Choate's day; and Locke, Edwards, and Stewart con- tinued to be required in the revised curriculum of 1822.

In the Harvard Laws of 1816, Locke, Stewart, Burlamaqui, Paley and Enfield were all likewise required, Locke's Human understanding having been made a text-book about 1737. "Seniors recite Locke," says Stiles, 1779, when Edwards was also used at Yale. The interesting Dartmouth library records show that as early as 1774-1777, Locke's "Essay on the Human Understanding" was drawn by students some 32 times, Edwards "On the Will" 22 times, and that all these text-books were in the college library in Webster's day. The continuing use of Locke and the high opinion entertained of him by Seniors is evidenced in Webster's graduation oration, and in the correspondence of himself and his brother Ezekiel when the latter was a Senior, 1803.

The curriculum was well adapted to the vocations of the men of that time. Of 234 graduates in the seven college classes known to Webster (1798 to 1804) 41% became laywers; 25% ministers; 12% teachers; 8% physicians. 86% went into these four professions; less than 6% into business. In Choate's day (classes 1816 to 1822), the percentage of professional men was even more marked, 97 in the four professions: ministry 43 (an increase significant of the greater religious interest during this period) ; law 33 ; teaching 12; medicine 9. In the fourteen classes known to Webster or Choate, the percentages were: lawyers 35; ministers 33; physicians 13 ; teachers 12. For the first fifty years, the percentages are almost identical, slightly larger for lawyers, and smaller for ministers. The most striking thing is the constant and overwhelming number going into the four professions. In the classes known to Webster or Choate, and the twenty-six classes under the 1796 curriculum, 93 percent became lawyers, ministers, physicians or teachers. In the first fifty years, 90 percent entered these four professions. In a college where nine out of ten men were to follow the learned professions, the emphasis on literary expression, philosophy, theology, and principles of law was admirably adapted to a world keenly interested in those subjects and in the type of men who could expound them. At Yale during the same period, 1797-1819, the percentage going into law, ministry and medicine is similar, with a smaller proportion becoming teachers. Over 80% entered the four learned professions at Yale.

, The training was not chiefly for the ministry; less than a third became ministers. The education was as excellent for lawyers, teachers and public men as for ministers. Professor Dixon's statistics in the Yale Review for May 1901, show that during the first 125 years at Dartmouth only 19% became ministers, 30.7% lawyers. The ministers were in a minority in every decade;, and fewer than the lawyers after 1790. The Dartmouth of Webster and Choate did have the passion for public service in state as well as church so characteristic of Puritans- and Calvinists of whom Eleazar Wheelock was so confessedly an example. Webster and Choate had a large amount of this and other Puritan traits, as the investigator will be surprised to learn from a careful study of their orations, letters and personal characteristics.

Webster's training in writing and speaking we learn from four sources: the regulations of 1796; his own statements;

seventeen printed orations or compositions ; the records of his literary society. In accordance with the laws of 1796, Webster and Choate would have been obliged to "declaim before the officers in the chapel on Wednesday" and in Senior year to engage in a "forensic disputation" in chapel before both students and faculty, the "Wednesday rhetoricals, " which were endured for a century.

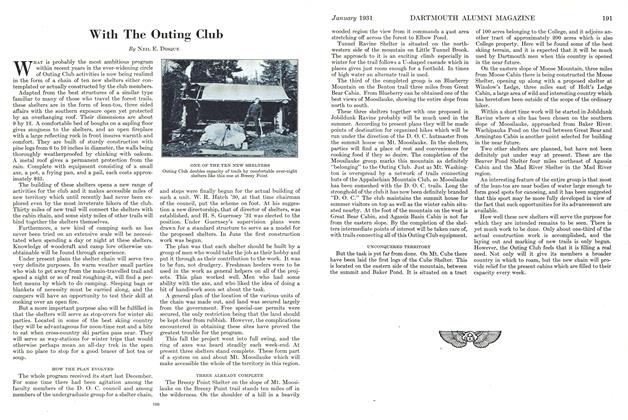

The only known example of Webster's college "compositions," about 500' words, written in his Sophomore year, advocates on clearly reasoned grounds the acquisition of Florida, twenty-one years before the event. In thirteen articles printed in the village paper, TheDartmouth Gazette, his Junior Year, the ponderous rhetoric of the eighteenth century and the eighteen year old boy is relieved by occasional flashes of imagination. "On swiftest pinions cut their downward course," and "when giddy sea boys on the tottering masts" are perhaps echoes of Milton and Shakespeare; but they are at least arresting echoes. Appropriately signed "Icarus," his verses reveal a country lad's appreciation of wind-swept mountain and sea, the latter likely seen at Hampton after the habit of Exeter boys. The following lines give Webster's boyish foretaste of a Dartmouth Outing Cabin, with ski-runners at Thanksgiving dinner.

"in tranquil peace, And joyful plenty, pass the winter's eve. Around the social fire, content and free, Thy sons shall taste the sweets Pomona gives, Or else in transport tread the mountain snow, Or leap the craggy cliff, robust and strong." The "sweets Pomona gives" is eighteenth century rhetoric for Whittier's : "The mug of cider simmered slow, The apples sputtered in a row."

The whole passage from "Snow Bound" suggests Webster in his Sophomore and Junior winter vacation,"the master of the district school," from "Classic Dartmouth's college halls", "large brained, clear-eyed," "born the wild Northern hills among, from whence his yeoman father wrung by patient toil subsistence scant."

The Junior year Fourth of July oration has touches of that strong national spirit and reverence for constitution and union that foreshadow the Reply to Hayne in 1830, and the Seventh of March speech, 1850. The criticism of "emptiness" in parts of the oration Webster himself recognized as just; and set himself to remedy this by a study of English authors"particularly Addison—with great care."

A distinct improvement appears in his graduation "Oration on the Influence and Instability of Opinion" before the United Fraternity, not printed from the manuscript until 1903, and apparently unknown to Professor Richardson. The dangerous tendency to rest decisions upon opinion and prejudice is attacked with an insight sadly prophetic in this college boy of nineteen condemning "the turmoil of passion and prejudice," and propaganda methods like those employed by his embittered political opponents in 1850. Webster in 1801, saw the dangers in "impatience of enquiry" and "blind obsequiousness to received opinion, taking things at second hand and admitting them to a creed without care or examination." He advocated "a free candid spirit of enquiry, a determination to appeal to selfjudgment," to arrive at "Principles" based upon investigation, after the manner of Locke and Newton. Choate, examining the manuscript, was struck with its "copiousness, judgement and enthusiasm, " a happy description of Webster's college writing. Choate's discriminating analysis of Webster's reading and thinking reveals the college boy's eager study of "how to get at truth:" "The science of proof which is logic; the facts of history, the spirit of laws." Webster's criticism of this "sufficiently boyish performance" and his other college writing reveal both his ambition and the secret of his mastery of style. "I had not then learned that all true power in writing is in the idea, not in the style, an error into which the Arts Rhetorica, as it is usually taught, may easily lead stronger heads than mine." To correct himself, he not only read "with great care," but also taught himself to think and speak simply. "I remembered that I had my bread to earn by addressing the understanding of common men—by convincing juries and that I must use language perfectly intelligible to them." "That is the secret of my style, if I have any."

On Webster's social and economic life new light is shed by his college and store bills. Contrary to traditions that he roomed in the Farrars' house on South Main Street his first two years, and in Dartmouth Hall his Senior year, the Treasurer's accounts prove he roomed in a college dormitory for the first three years, and in Senior year occupied a room outside of College. That he roomed in a private house Senior year is confirmed by his letter to Bingham, Dec. 29, 1800. This first-hand evidence eliminates unsubstantiated traditions, and strengthens the case for Webster's rooming at the Webster cottage, North Main Street and Webster Avenue. The evidence for this rests not merely upon unbroken and uncontradicted traditions, but upon the contemporary record of the careful William Dewey, repeated within the house itself to another cautious witness Miss McMurphy, and written down by her later.

Webster paid a total college bill of $88.34 for three year's room-rent, four years' tuition and incidentals, interest, and Commencement tax. Choate paid only $20.58 before graduation, the college accepting his note for $84.12'. No wonder there were those who loved her! Long delayed payments, only settled on the eve of graduation, were the rule. For twenty-five months Webster paid nothing; then, Junior Year, $18.40, earned teaching school at six dollars a month in Salisbury. His board he paid by writing for the Dartmouth Gazette; his other expenses by borrowing $26.99 from Lang, storekeeper and money lender. His room rent averaged $4.09 a year. With board at .College Commons! one dollar a week, this makes $59.89 for tuition, room, and board. For all items save the loan, Webster paid Lang $43.36, a total known expense Junior Year of $103.25. $100.00 would, "on a decent economic plan," cover annual expenses "including board, tuition, room, wood and contingents," wrote John Wheelock, 1800. $125 was the estimate of Dr. Horatio Newhall, who attended Commencement 1819, when Choate graduated.

Getting into debt, Webster's one bad habit, was characteristic of the college and a period without ready money. Students were almost without exception seriously in debt to the college, owing her $5,700 in 1815; and one at least went through without paying a dollar in actual money. The college itself was never out of debt, and annually ran from 10 per cent to 30 per cent in excess of its income. In 1814 it owed on notes and salaries $7,436; at the close of the College Case nearly double that amount. Even in Webster's day the meagre salaries could not be met. During 1797-1801, the college annually fell short on its salary list $250. and actually paid only $1906.00 on an average for its total annual salaries for teaching and administration. John Wheelock, President and Professor of Civil and Ecclesiastical History (who taught the Senior Class, including Webster, "Natural and Political Law") received $767; John Smith, Professor of Ancient Languages, Pastor of the College Church, and Librarian, $551 for this triple threat; Bezaleel Woodward, Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy, and Treasurer, $400; Roswell Shurtleff, Tutor, $234. Four men constituted the entire teaching and administrative staff of the college in Webster's day; five in Choate's time, not including part-time instruction in Chemistry given by a Medical College Lecturer.

The charges to Webster in the "Student Accounts" at Richard Lang's store, supplementing the direct testimony of eyewitnesses, enable us to visualize the eighteen year old boy in his "chamber," with its hanging of "7 yds. chintz ss. 6d.sitting at his desk, his swarthy face thrown into relief by the dim light flickering from "candle stick 3/4" flanked by "snuffers 2/6;" and with ink made by himself from "ink-powder 9dwriting on the many quires of paper and with one of the hundred quill pens bought his Junior year; so absorbed in his work that he pays no heed to the sheets of paper blowing past the waving chintz and out of the window, until he ceases writing and passes from the room to deliver his oration. On Sunday, with his "Salmbook 4/6" under his arm, Black Dan is taken for an Indian by the Deweys as he passes down the aisle of the meeting house. In his Junior year, such items as "best laced clock'd cotton hose 15/ 6" ($2.59) , good broadcloth and expensive gloves give hints of the happy social life in "the charming village" with classmates and their sisters and cousins, and "Mary la bonne," Professor Woodward's daughter, "lovely as Heaven, but harder to obtain."

The store accounts and letters reveal a frank, warm-hearted, sunny, lovable boy, fond of books and friends. They save one from overemphasizing the more serious side portrayed in the later remin iscences. Webster was a wholesome college boy of fifteen to nineteen, a keen student given to rapid and concentrated reading and "close thought," brilliant at both writing and speaking, an acknowledged leader, fond of the best literature, but also keenly interested in newspapers, politics, politicians, good talk and a game of "Nap," and with a zest for "fishing, shooting and riding." The two sides of Webster's college career are suggested in a classmate's testimony to "the generous and delightful spirit he showed among his earliest friends" and his "faculties which left all rivalship far behind him," "whenthe first year was passed."1 The debt to Dartmouth of the shy awkward, sensitive, farmer's boy, is suggested by the steady growth in both intellectual and social powers, amply witnessed by himself and his contemporaries. There is no question of bad habits, nothing to conceal . about Webster. In the matter of liquor, he conformed to the custom of the best people of his day, purchasing in moderation just the average amount bought by other students, astonishingly small as compared to his austere President John Wheelock who bought more in a month than Webster in a year. Even his caustic classmate Loveland found ambition Webster's only fault or weakness in college.

His fellow members who knew him intimately, especially in his debating society, wrote: "The powers of his mind were remarkably displayed by the compass and force of his arguments in extemporaneous debates." "His orations in the society and occasional written exercoses, all showed the marks of great genius and great familiarity with history and politics for one of his years." Half a dozen addresses or orations (one of which received the somewhat unusual distinction of a "vote to reposite in the annals of the United Fraternity an oration delivered by Junior Webster," and another the place of honor as the Commencement oration of his fraternity) show a remarkable progress from his experience at Exeter, where he was never able to rise from his seat to speak the many pieces he committed to memory. Webster was honored with half a dozen offices as "Inspector of Books," "Librarian," "Dialoginian to write a dialogue for exhibition at the next Commencement, "Orator," "Vice-president," and "President."

The records of the weekly debates, in which Webster took active part, reveal undergraduates' views of questions of .their day, "Would it be advisable for students while at college to read Dr. Hopkins System of Divinity. No." Six months later, with undergraduate inconsistency, they returned thanks for a copy of Dr. Hopkins' book—very likely in each case without reading it. "Are great riches conducive to happiness? No." "The spendthrift is more; advantageous to the public than the miser." "Marriage is conducive to happiness." "Which is the more suitable for a wife, a widow or an old maid? The wdo." "Is familiar intercourse between the sexes favorable to virtue ? Ans. Conditional." With equally wise caution they answered to the further query: Ought separate schools, to be provided for the education of different sexes ? Ans. Conditional." As to curriculum and "activities" they reached these sage conelusins. December 5, 1797, they manifested their interest in chemistry (just introduced by Dr. Nathan Smith) by this debate. "Is it beneficial for students to attend chemical lectures while in college. Yes." "It would be as advantageous for students of this institution to study the French language as the Greek." "Scholars should attend as much to ancient as modern writing." "Spending our time in frequent company is not beneficial to student at College." "Gambling is not justifiable." "A college education is conducive to happiness." "Students should not neglect their classical studies for the purpose of reading history," a decision doubly sound because of the evil of neglect, and because of the type of history available when Rollin's Ancient History was the college bestseller. To the question, "Is the study of the Latin language preferable to Greek?" there is, alas, no answer recorded. To the query, "Would it be profitable for students to attend to learning the art of dancing," they cautiously answered, "Conditional." The decisions reflect the spirit of their time in opposition to France, slavery, sumptuary laws; and in support of foreign immigration, capital punishment, and in general of rather a strict view of moral questions. No discussion of drinking has been noted, or of religion save the negative decisions regarding desirability of reading "Dr. Hopkins system of Divinity," or of "discussion of theological questions in the United Fraternity." These wise young Daniels came to one judgment which combined sanity and humor. "Does eloquence tend to the investigation of truth? No."

Membership in the debating societies was so general that the opportunities for training in writing and speaking were open to practically all who desired them. There were the inevitable rivalries between the two societies in their "fishing" for candidates. In Choate's day and thereafter, the whole class was assigned to one or the other society according to odd or even" places of the names as they occurred in the alphabetical list of the class.

Choate, like Webster, was a very active and especially trusted officer in his society. As Librarian and member of the "Committee of Safety," he received a vote of thanks for his timely removal of the Social Friends' library to his own room, and his share in successfully resisting the attempt of the Professors of the rival "Dartmouth University" to seize it, in 1817. Rufus Choate's first recorded appearance in court was not as advocate but as defendant, arrested on charge of "riot," when he was bound over to the Grand Jury which wisely declined to indict either "University" professors or "College" students. There was something challenging about the courage and resourcefulness in President. Brown, the faculty and students of the College during this fight for existence. It is characteristic of the time which bred eighteen college presidents and twenty-eight professors that Choate in this most trying and discouraging year when the state courts decided against the college, wrote home: "The situation I most envy is that of a Professor in a College." Three days later, this scholarly but riotous Sophomore was arrested for "thronging" the professors.

Of Choate as a presiding officer, Chief Justice Perley, then a Freshman, records his admiration and adds, ''Mr. Choate was required as president, by .the rules of the Society, to give his decision upon the question, whether ancient or modern poetry had the superiority." "The decision on the Contemporaneous (sic) question by the President did honor to his station and himself," is the confirmatory record of the Secretary. Choate decided in favor of the ancients. The records of fines, excuses for absences, "thin meetings, " and postponed debates in Choate's day show characteristics of undergraduates of all times. The prize alibi-artists of 1818 gave this excuse for absence from debate: "the Junior Class being very much engaged in eclipsing the sun and moon." The seriousness of the better men is illustrated by Choate's younger brother, Washington, whose unpublished letter speaks of spending three or four days writing "A defense of Systematic Study" for his Society debate.

1. Cited by George Ticknor, "Remarks on the Life and unitings of Daniel Webster," reprinted (with additions) from American Qtmrterly Review, 1831. Published anonymously, not assigned to Ticknor in Dartmouth library catalogue, and apparently (like Professor Felton's article in 1852 Review) not used by Professor Richardson.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1927 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS SUGGESTS FOOTBALL MODIFICATIONS

April 1927 -

Article

ArticleEXCEPTIONS

April 1927 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

April 1927 By Herrick Brown -

Sports

SportsDARTMOUTH QUINTET WINS FIRST LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP

April 1927 -

Article

ArticleElections and More Elections

April 1927