Dean of Freshmen

Once upon a time—-and each alumnus will know how long ago—it was rare enough to be noticeable for a student to be. forced to sever his connections with Dartmouth College on account of his scholastic failures. As Tom Groves would say, "A fellar had to work like the devil to flunk out of College." Moral turpitude was more apt to make a man emigrate than deficient scholarship. Some years ago, however, it was decided that a student failing in nine semester hours would do well to heat up his scholastic ardor from a distance; so for many years students losing nine semester hours by failures or more than nine by failures and overcuts were automatically separated from college. In addition, men on probation for scholastic failures (six semester hours lost) who in the succeeding semester lost six semester hours by failures or more than six by failures and overcuts, were also automatically deleted from our active lists.

Up to 1922 the return of these men to college was about as automatic, and hence wooden, as was their separation. Any one separated was compelled to stay out at least one semester and usually two. He then petitioned the Committee on Administration to be allowed to return. This petition had to be accompanied by testimonials, (these usually resembled Peruna advertisements,) from the man's employers indicating that he was assiduous in his duties, regular in his habits, and good to his father and mother. For the years during which the writer sat on the Committee on Administration he never knew one of these petitions for return to be insufficiently propped up by testimonials and hence to be denied. In other words, return was automatic with out any knowledge on the part of the Committee as to the applicant's chance of success in college which was additional to that at hand at the time he was separated.

At the time applications for admission to the Freshman class became excessive, it seemed to some of us that this granting of a second chance to every man who wanted it with the resultant denial of even one chance to some applicants was unfair and unsound. As a result a statistical study was made of several hundred men who, separated for scholastic failures, had been allowed to return after proving that they had driven so many miles or pumped so much gasoline since leaving college. The scholastic record of these men upon return to college w~as entirely conclusive. Somewhere between 5% and 10% only of the hundreds who returned got their degrees. The remedy for this unfair and unsound policy of the second chance was obvious and simple. Consequently, in October 1921 the Committee on Administration, and eventually the faculty voted : That in view of the fact that the accommodations at Dartmouth are insufficient to grant the privilege of admission to more than a small proportion of the number of young men of marked potentialities who desire the opportunity of entrance, and in view of the fact that the number of such men who can be given admission is restricted still further by the periodical readmission of some number of men who have heretofore failed to qualify in college work, and in consideration of the fact that statistics prove that only a small proportion of those so readmitted to Dartmouth College after failure show later ability to qualify with good standing, therefore, it be declared to be a policy of the college that hereafter men separated for failure to observe scholastic standards shall not be given the privilege of readmission.

The main argument presented by the formulators of the above regulation was that practically all the factors of importance in determining whether a given student who had failed nine semester hours had any chance of doing college work were available at the time of separation. In other words, if there were no exceptional factors in his case at the time of his separation there was no likelihood of his succeeding on his return, even though he had been prompt and sober at the mines since. It was equally obvious, however, when capital punishment was provided by the above regulation that some men failing in at least nine semester hours should be given a second chance before decapitation; namely those men whose individual cases seemed to warrant exceptional treatment, or to give hope of future scholastic success. This paper is designed to analyze statistically the history of such exceptions as have been made since February 1922, when the regulation of non-return first became active.

During Sophomore year, that is in February and June, 1922, eight exceptions were made for men of the class of 1924. Of these eight, three were eventually separated, two withdrew and three secured their degrees. Three exceptions were made for this class in Junior year, all of whom secured their degrees. Two exceptions were made in Senior year, one of whom graduated and the other withdrew. In all, therefore, thirteen exceptions were made in the class of 1924, seven of whom graduated, three were separated, and three withdrew.

For the class of 1925, six exceptions were made in Freshman year. Two of these men were eventually separated, three withdrew, and one graduated. In Sophomore year there were twelve exceptions, six of whom graduated and six withdrew. In Junior year there were five exceptions, yielding one separation, three degrees and one withdrawal. In Senior year came four exceptions, three of whom were separated the following semester, and one graduated. Altogether, twenty-seven exceptions were made for 1925, eleven of whom graduated, ten withdrew from college, and six were separated.

In the class of 1926, six exceptions were voted in the Freshman year, two of these have graduated, three withdrew, and one was separated. In Sophomore year nine exceptions were made, resulting eventually in three separations, two withdrawals, and four men in good standing. In Junior year there were three exceptions, of whom one withdrew and two have graduated. In toto, for this class there were eighteen exceptions, distributed eventually as four separations, six withdrawals, and eight in good standing.

For the class of 1927 there were nine exceptions in Freshman year of whom five are now in good standing and four were separated. In Sophomore year there were six exceptions for this class, three of whom were afterwards separated and three remain in good standing. In Junior year six exceptions were made one of whom was eventually separated and five are in good standing.

For the class of 1928 five exceptions were ordered in Freshman year three of whom eventually lost out, one withdrew, and one has continued in more or less good standing. In Sophomore year ten exceptions were made nine of whom are now in first-class standing and one, the most competent of the group, was separated.

During Freshman year ten exceptions were made for the class of 1929, two of whom have been separated and eight remain in good standing.

The following table gives the complete results since the vote in question wras adopted.

February 1922—February 1927 Exceptions Separations Withdrawals Good 'Standing 104 27 20 57

The writer, believing firmly that there is much joy in Hanover over one sinner that repenteth, feels that the fairly complete salvage of at least fifty-seven out of one hundred and four men is a rather remarkable vindication of the intimate consideration that has been given each case by the class officers, the Freshman Faculty Council and the Committee on Administration. In addition to fifty-seven who have secured salvation, the with drawal group is made up largely of men who withdraw with the privilege of return, in other words while at least officially in good standing. One of these, for example for whom exception was made after he had failed nine semester hours in Freshman year, withdrew at the end of Senior year when he had considerably more than enough points to graduate but lacked a few hours of graduation. On the other hand, it is interesting to note that one exception who eventually got his degree, took ten semesters and three summer schools in which to do it. That reminds me of a vote once proposed to the Committee on Administration by one of the faculty wits. We were discussing how we gracefully could separate a certain individual who led a charmed life throughout his course and had nearly reached Senior year. The wag proposed the following, "Moved, that Peter Poe, never having been off probation, be separated from college."

Further, it is interesting to observe that a goodly number of exceptions were made purely on account of sickness, without any positive opinion on the part of the Committee that the men would eventually make good. In this connection, the writer thought he might tabulate the reasons which in general had led the Committee on Administration to make exceptions, but he found upon study, much to his delight, that the number of reasons was comparable only to the number of cases. In other words, each case was an individual one where much w-as known about the man in question. Perhaps the predominant reasons for making exceptions have been obviously good college records, demonstrated special ability in someone or more subjects, exceptionally bad luck in the semester examinations, unfortunate living conditions, aggravated home conditions, illness, exceptionally good preparatory record, psychopathic cases, sudden and inconsistent falls from grace. If it were not too personal I would tell of some individual causes for exception that would be much more interesting in an article like this than the above generalities.

In conclusion, it is interesting to analyze the; one hundred and four exceptions according to their class ratings. It is of course obvious that the poorest results come from the Freshman exceptions. In spite of the fact that such exceptions are recommended by the Freshman Faculty Council, a group of men who know the students concerned intimately, nevertheless one or two semesters in college is an insufficient basis for making any big gamble. However, it decidedly should be the policy to give Freshmen the benefit of every doubt. Many colleges give Freshmen a full year before making any separations. Exceptions made in Sophomore and Junior years should turn out pretty well. Nearly all such are made for men who have proved their scholastic ability to do our work. As a matter of fact about two- thirds have done this very thing. It is simply a question of estimating the grip love or the devil has on the man. Senior exceptions should turn out badly. When a Senior fails nine hours he has dropped his check rein, broken his martingale and is almost bound to keep on stumbling.

Excep- Separa- With- Good tions tions drawals Standing Freshman 36 12 7 17 Sophomore 45 10 10 25 Junior 17 2 2 13 Senior 6 3 12 Totals 104 27 20 57

It may be of interest to observe that during the five-year period in which these one hundred and four exceptions were made a total of four hundred and fifty-five men were separated from the college for scholastic failure, made up of nine Seniors, thirty-one Juniors, one hundred and eighty-two Sophomores and two hundred and thirty-three Freshmen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

April 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1927 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS SUGGESTS FOOTBALL MODIFICATIONS

April 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

April 1927 By Herrick Brown -

Sports

SportsDARTMOUTH QUINTET WINS FIRST LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP

April 1927 -

Article

ArticleElections and More Elections

April 1927

E. Gordon Bill

-

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1931

NOVEMBER 1927 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

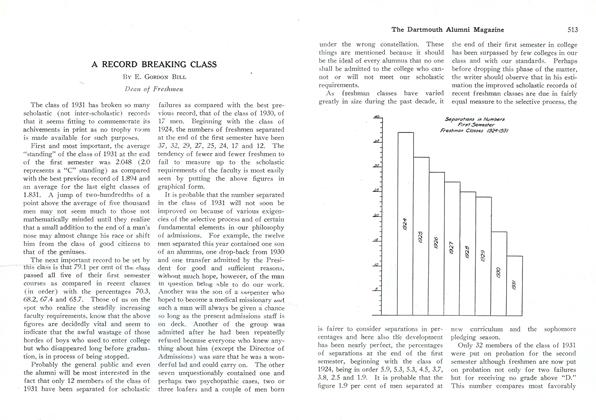

ArticleA RECORD BREAKING CLASS

APRIL 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

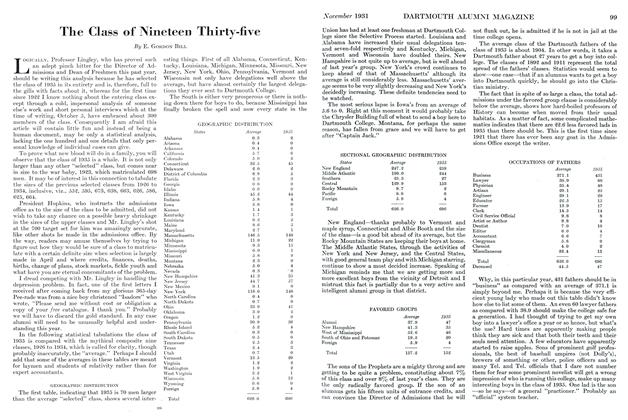

ArticleThe Class of Nineteen Thirty-five

NOVEMBER 1931 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

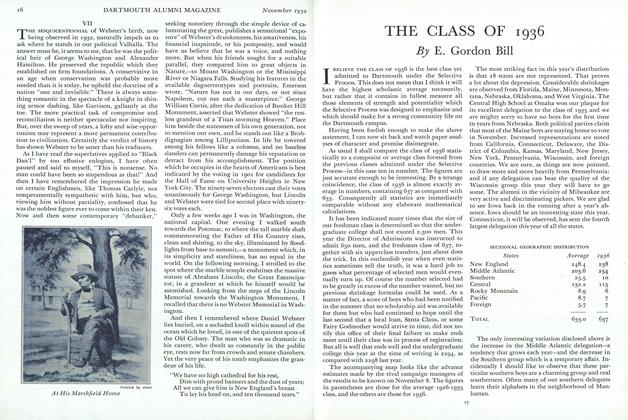

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1936

November 1932 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

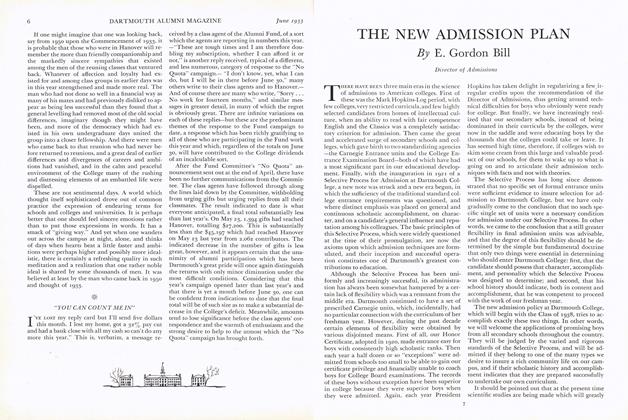

ArticleTHE NEW ADMISSION PLAN

June 1933 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

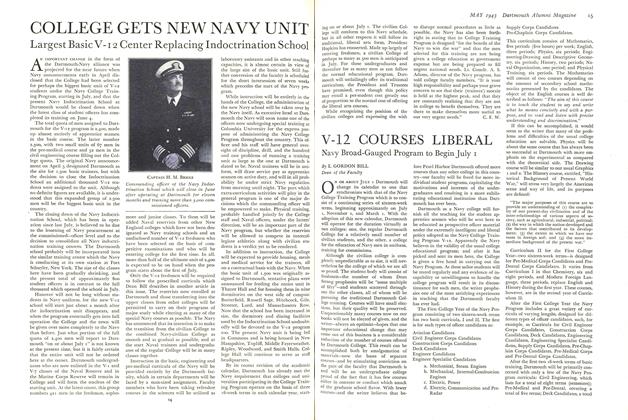

ArticleV-12 COURSES LIBERAL

May 1943 By E. GORDON BILL