Moral education faces its own thorny issues.

Students today are growing up in a morally complex environment. They can look to such moral exemplars as Mother Theresa, Bishop Tutu, local volunteers who feed the hungry, and social workers who offer shelter to the homeless. But they are also confronted with the moral failings of prominent figures in government, the church, and business. What are they to make of a military hero who lies to Congress in the name of a self-determined higher good? Or of religious leaders who threaten damnation to the sinful, yet indulge in the very acts they claim to despise? Or of business people who value shareholder profit over public safety?

Perhaps it is not surprising that many of our youth are in crisis. Adolescent drug abuse, pregnancy, and suicide are on the rise. While there is much hand-wringing about our youth, there is no consensus about how to guide them through moral straits. Whose values, whose morality, should our youth learn? Who should be the primary moral educators: religious organizations, schools, families? Indeed, in a pluralistic society, can there be agreement on moral education?

in the autonomy and privacy it allows students, or in its use of shaming, the school is a moral arena.

Schools can take several approaches toward moral education, including values clarification, character education, developmental moral educaction, and the new field of morality as care. Of these, two are dominant: character education, which focuses on teaching what is right and what is wrong, and developmental education, which focuses on how to decide what is right and wrong. Character education, grounded in the ideas of the French sociologist Emile Durkheim, views morality as the result of the inculcation of society's values on the individual. Developmental education, based on the theory of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, holds that the acquisition of morality is a developmental process—and that people's capacities for moral reasoning change as they grow.

The leading American scholar in moral psychology and moral education for the last 2 0 years has been Lawrence Kohlberg. Building on Piaget's theory, Kohlberg delineated six stages in the process of developing a sense of moral judgment. He contends that age, education, and experience influence a person's sense of justice. Developmental moral educators use these stages as a guide to understanding children's growth and their capacity for moral reasoning.

Kohlberg found that if people are asked to evaluate what is just in a certain situation, the range of answers tend to fall into predictable patterns. Here's an example. Heinz is an elderly man whose wife is seriously ill. Medicine that could save her is available from a man who is demanding an inflated price that Heinz cannot pay. He considers stealing the medicine. What should Heinz do?

Kohlberg found that young children tended to say that Heinz shouldn't steal the medicine because he would get in trouble. This is what Kohlberg calls a Stage One punishment-and-obedience orientation. Older children, such as sixth-graders, tend to give answers within the Stage Two instrumental-relativist orientation—saying either that Heinz shouldn't steal the medicine, because what did his wife ever do for him; or yes, Heinz should steal it because he needs his wife to cook for him. A Stage Three "good boy-nice girl" answer would be: "Of course he should steal the medicine, because he is a good, loving husband." As an orientation sensitive to peer pressure, Stage Three is the category into which much of adolescent thinking falls. Stage Four's law-and-order thinking is: "No, Heinz shouldn't steal, because people can't just do what they want; they have to follow rules." The next two postconventional stages do not provide quick answers to Heinz's dilemma. At Stage Five people understand that values are relative to their group but should usually be upheld because they are the social contract. At Stage Six moral reasoning follows abstract universal ethical principles.

Kohlberg's theory has been criticized recently by scholars who contend that his research—which was originally carried out on men only represents a male perspective. Carol Gilligan claims that when women make moral judgments they are more likely to take into consideration such questions as the effect the action will have on other people. Thus, a woman asked to judge Heinz's quandary would likely want to know more about the situation and try to assess all possible personal and social ramifications before making her judgment. Gilligan's research greatly widens our perspective on moral development—and presents profound challenges to all those involved in moral education.

For further reading, I recommend the books below.

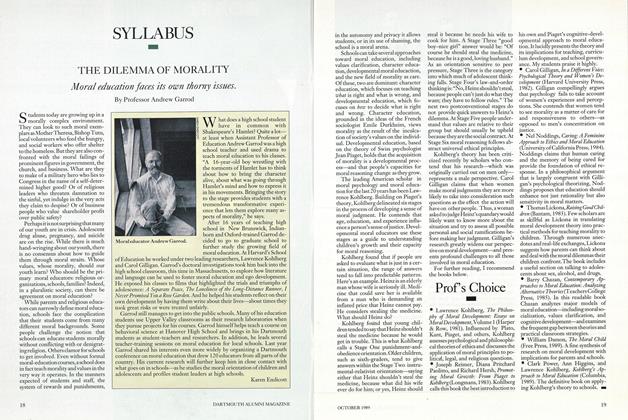

Moral educator Andrew Garrod

What does a high school student have in common with Shakespeare's Hamlet? Quite a lot at least when Assistant Professor of Education Andrew Garrod was a high school teacher and used drama to teach moral education to his classes. "A 16-year-old boy wrestling with the torments of Hamlet has to think about how to bring the character alive, about what was going through Hamlet's mind and how to express it in his movements. Bringing the story to the stage provides students with a tremendous transformative experience that lets them explore many aspects of morality," he says. After 16 years of teaching high school in New Brunswick, Indianborn and Oxford-trained Garrod decided to go to graduate school to further study the growing field of moral education. At Harvard's School of Education he worked under two leading researchers, Lawrence Kohlberg and Carol Gilligan. Garrod's doctoral investigations took him back into the high school classroom, this time in Massachusetts, to explore how literature and language can be used to foster moral education and ego development. He exposed his classes to films that highlighted the trials and triumphs of adolescence: A Separate Peace, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, INever Promised You a Rose Garden. And he helped his students reflect on their own development by having them write about their lives—about times they took great risks or were treated unfairly. Garrod still manages to get into the public schools. Many of his education students use Upper Valley classrooms as their research laboratories when they pursue projects for his courses. Garrod himself helps teach a course on behavioral science at Hanover High School and brings in his Dartmouth students as student-teachers and researchers. In addition, he leads several teacher-training sessions on moral education for local schools. Last year Garrod shared his interests even more widely by organizing a Dartmouth conference on moral education that drew 120 educators from all parts of the country. His current research will farther keep him in close contact with what goes on in schools—as he studies the moral orientation of children and adolescents and profiles student leaders at high schools. Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBoredom's Uses

October 1989 By Joseph Brodsky -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDon't Call It "The D"

October 1989 By Michael T. Reynolds '90 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the Massacre

October 1989 By Jessica Smith '89 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureBUBBLE AND PEAK

October 1989 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1989

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresident Goes Abroad

May 1929 -

Article

ArticleA. Tribute from President Hopkins

December 1951 -

Article

ArticleProject to Help the Poor.

MARCH 1966 -

Article

ArticleBowled Over

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 -

Article

ArticleNoted Townies of the Past and Present

February 1935 By "Old Timer" -

Article

ArticleSculptor to the Great

NOVEMBER 1992 By Heather Killebrew '89