(Being the Musings of Maddox, Umpty-Ump, on That Occasion)

Maddox lay on his bed in the top story of College Hall, courting repose which somehow delayed to come. Small wonder that; for, although the college clock had just relayed the news that it was already the second hour ayant the twal, a small but determined band of vocalists below persisted in the tuneful information that they had been laboring assiduously all day on the railroad.

Maddox's room contained a practicable couch and a practicable chiffoniere containing his chiffon. At its far end was a jumble of furniture, abandoned for the ensuing few months by its undergraduate owner and duly ticketed for autumnal transfer to Russell Sage. Maddox had inspected it with interest. It included, among other articles of bigotry and vertu, the windshield of a Ford car, two pair of skis, a hard-bitten desk, a Morris chair and some crates of indeterminate contents.

It had been a full week-end, he reflected. He had come to Hanover on Friday in a conveyance not so much as dreamed of when, some 35 years before, he had first approached that fount of learning—to wit, in his faithful car which answered somewhat uncertainly to the endearing name of Maud. Maud was now parked under an elm beside the campus. At least Maddox hoped it was still there, although dubious lest some nocturnal party of revellers might decide they wanted a cruise in the waning moonlight. Meantime the sounds of such as protracted day far into night continued to steal upward from the porch beneath declaring that "the cup was at the lip in the pledge of fellowship." Maddox rather fancied that it had been.

Somehow, he ruminated, the town hadn't seemed so full of people as sometimes.. Of course there must be about the usual number, but the advent of the agile motor had produced its effect. Scores spent the day at Lake Morey or Lake Tarleton who used to stay in town. People came and went more flexibly than they used to do when all access to and egress from Hanover had been afforded by the portals of "the June" and the accommodating trains of the Boston & Maine. The June, while maintaining its ancient sounds and smoke, had revealed itself recently to Maddox as shorn of its old brick station. In its place were some detached and dingy buildings of wood, replacing the structure destroyed a decade ago by fire, and to be reached only by a perilous passage across half a dozen tracks, on which persistent shifting engines caused long strings of cars to parade up and down. It seemed that Norwich station was all but totally ignored by those for Hanover bound. One no longer waited interminably for the upriver train, beguiling the interval with chicken pie and other Comestibles, the identity of which was artfully concealed by little disguises of flyscreen. He wondered what had become of old "Plenty- of-Time." Gathered to his fathers no doubt, with plenty of time to while away before Gabriel should sound his last trump, or his celestial counterpart of that famous dinner-bell with which every arrival at the June used to be greeted. No one went to Norwich now. One alighted, so they told him, at the Junction and was wafted in a bedizened motor-bus to Hanover before the up-river train had even changed engines. Maddox wondered what the agent at Norwich did with his idle time-—he must have a lot. Things had got back to the stagecoach era; only, instead of four horses hauling a Concord coach laboriously over the hills, a thousand individual stages, each hauled by the equivalent of 27.3 horses, at the very least, brought the multitude quite as quickly as ever they came by train in Maddox's own time.

His mind ran back over the past three or four days. Friday hadn't been especially exciting. The Alumni Council had convened at 4 p. m., and Maddox had taken his accustomed place at that round table in Wentworth Hall—a table with a hole in the middle, which made it look rather like a huge doughnut—and heard reports. The Alumni Fund, it seemed, might obtain the established quota or might not. George Morris hoped it would, but every one had the customary tremors for fear the close of the campaign would show the goal still out of reach by only a beggarly hundred or two. Maddox had been through that oft before—and hoped for the best. Wonderful how those alumni played up, year after year! Was there another bunch like them in the world? Maddox didn't believe there was—nor another president like Hop. Hop had come to the dinner that night and, while he said he wouldn't make a speech, the Council had bombarded him with questions sufficiently pertinent to bring out the equivalent of two or three speeches—all of them corkers ; for Maddox never heard Hop without renewing his conviction that in him Dartmouth had been put into uncommonly safe, sane and sensible hands.

What a privilege to be alive at this best of all possible times, in this best of all possible colleges ! Maddox hoped it would go on being the best. No reason why not—if they didn't get too enthusiastic and over-extend. Maddox somehow felt that 2000 students should be quite enough. Even those put a serious strain on the old traditions, especially in an age when old traditions frequently produced an undergraduate snort which Maddox hoped came from the inconsiderable few. But 2000 students—that was five times the number in Maddox's time, including the raucus Medics, who were described as being "a little lower than the angels." Let Dartmouth be content with that! That lifted her out of the "little college" category, over which deep-browed Dan'l had wept those timely tears. Maddox fell to wondering whether, in less than half a century, such sentiments as these would seem over-cautious and hampering—but felt willing to chance it. He was proud of the bigger Dartmouth; but somehow he felt he didn't want to see it too darned big.

Those seniors—stretching all the way from one end of the campus to the other, in double files, and then well around the corner! Why, that one class, with its nearly 400 survivors, about to get their coveted parchments, would have made a whole college, and a whole Medical school thrown in, a generation ago; and the recent losses by the wayside had been so few this year that they said there would be room for not over 550 freshmen in the fall. Good—for that showed the selective process was working out admirably. "They" told him something about the requirements, now, and Maddox wondered if he could ever have won an A.8., if things had been as strict when Umpty-Ump was on the scene. He doubted it—and yet, somehow or other, the graduates of today didn't seem to his casual eye to be so much more erudite after they got out. But they had to work harder while they were there, and the wonder was that with all that intensive labor they had time to do so many other things and do them superlatively well. That band, for instance. That orchestra. Those dramatic fellows with their original plays.

Class day, the next afternoon, had been about the usual thing. Being sure that it would be, Maddox had omitted listening to the wise cracks at the Bema, where he supposed the usual chaffing would be appreciated most by the members of the class who would understand all the allusions, and took up a strong position by the stump of the old pine to hear the talk there and see the churchwardens smashed after the class smoker.

There was the usual oration there—it had about it a faint tang of militant pacifism and of youthful confidence that the errors of an incompetent generation were about to be redressed by a hopeful band which at least had learned how to think freely. "We shall make our mistakes," the speaker had charitably admitted, "but they will not be the old mistakes." M'addox wondered if that novelty would redeem them in the eyes of a generation yet unborn, and fell to speculating whether or not the world was really so different since the war. People had been told so, and told so often that it seemed they believed it. Maddox was just wondering if it was true. But the pipes were being tossed through the air now, and smashed into fragments against the decaying stump. The band was playing the crowd down the hill past the Observatory. Class day was over—and the showers hadn't come after all! In fact there was ideal weather all through —mostly bright, but not hot.

Then had come the inspection of "Dick's House"—that amazing memorial, combining utility and beauty, which perpetuates for all time in the college history the memory of a bright young life, cut short by an inscrutable Providence when it seemed fullest of promise. Dick Hall—worthy son of most loyal sire! Had there ever been such a labor of love as that which Dick's parents had performed when they planned and built this refuge for other ailing boys ? Was there in any country on earth such a glorious combination of home and hospital—such an infirmary in excelsis? It had been open daily, and all the world had come to see it. Maddox had gone back there again and again —each time to find something new and each time to wonder what word he could find to describe it. Certainly not "hospital," and certainly not "infirmary"— those words of ill omen and repellent connotation. Best of all, surely, to call it Dick's House, as they do. No one could give an idea of its completeness, its beauty, its comforts. One must see it.

There had been the reception at the president's new house—happily the fine weather had permitted a general inspection of its grounds as well, and music came trickling pleasantly from a pergola at the farther end. It was a genuine pleasure to see the president and his family so worthily housed, and to wander about the grounds, finding here and there familiar faces—collegiate and community faces. Hanover was rather more than a country village now, he reflected ; but there was a well remembered time when it was little, and intimate; and there were still some of the girls one used to take to parties—now grown into mature women, to be sure—but the past at least was secure!

Maddox hadn't been particularly thrilled by the theatrical performance of Saturday evening, although it was infinitely better than anything that could have been done in his own day in the line of what is now called a "Revue." Parts of it were excellent—like that famous curate's egg—but to ring in a finale with a lot of girls (real ones) in it, seemed to lift it out of the purely college category and make it rather like the commonplace effort of amateurs anywhere else.

It had rained a little, now and then, on Sunday—but not enough to do any harm to the course of events. Maddox looked back with more than the usual satisfaction on the Baccalaureate sermon—it had been delivered by young Mr. Aid rich of the class of 1917, now rector of a NewYork church which was once made more or less famous by a rather radical predecessor. The sermon was excellent, just the sort of thing for questioning young men, who, according to report, seemed inclined to challenge pretty nearly everything that the elders had regarded as truth. The preacher didn't ask them to accept any ancient dogmas. He only wanted them to think of God and his messengers with as much consideration as one would think of one's best friend, and to consider also the validity of the Christian teachings as the surest guide of life.

Maddox fell to thinking about this rising generation and its attitude toward Truth. Sometimes youth appeared to believe that the Truth—with a big, big T—must necessarily be highly unpalatable, and necessarily also at variance with anything the ages had ever experienced before. "Face the facts," he had heard class orators urge the assembled world—and the implication always was that no one ever willingly faced any facts; that by facts one meant something which no one wanted to face because facts are always and invariably unpleasant. Maddox wondered if a just God had never by any chance permitted a thoroughly agreeable fact to stray into the world?

Something especially ambitious had been attempted in the evening—nothing less than a performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony by the combined College and Community orchestra and chorus. The list of performers had revealed a composite talent, varying from the students and professors to the purveyors of local groceries and local ice, who sat behind the several instruments. Led by the energetic Mr. Longhurst, orchestra and chorus gave a vigorous interpretation of Beethoven's celebrated composition. It had never been one of Maddox's prime favorites, mainly because he found all but the two middle movements far too long and too repetitious—but that was no doubt his fault. It seemed to be regarded now as a confession of imperfect perceptions to prefer the Fifth symphony—but, being alone and intellectually honest at the moment, Maddox felt he did prefer it. That Hymn to Joy at the end of the Ninth, sung by a breathless chorus and by almost as breathless soloists hired in for supplement, was bound to leave one a little cold toward the Brotherhood of Man. None the less the performance was an amazing success—ragged in one or two spots, maybe, but the wonder was that it was done so superlatively well by amateurs, since such a titanic work must always tax the best professional's fully developed powers.

All through there had been the pleasant association of "reuning" classes—• Maddox loathed the word, but what else could one call them, conveniently? It was particularly good to see the '92 men, once more—they had been juniors when Maddox came to college—and the '97 men, who had been freshmen. Surely one did well to come back out of one's regular order, so that one might see the classes one would otherwise never see at all. That was not always possible, of course—and rather fortunately so, because if every one started coming back to Hanover out of his proper turn it might cramp the style of the entertainment committee. Maddox had heard the "annual reuner" mentioned as among the prize pests and blushed in the dark because much given to the pastime himself.

So it had been good to see the '92 fellows, quartered in South Fayerweather; and the '97s in North Mass. He wondered whether it was now an established custom to house the 50-year class at the Inn—for that was where they had parked '77, and a bully good place for them, too. Those '77 men looked younger now than they did (according to their published photograph) when they were back for their 35th, and they had made a particularly pleasant showing when on Monday afternoon they had gathered in the campus tent to answer to the roll call and maybe make little speeches to the multitude. Maddox was glad he went to that traditional reception—he always was glad, every year. Getting on himself, now, toward the point where the 50th reunion was distressingly visible! Must be gunning up a few well chosen words! He thought if he began soon he might be able to memorize them by 1944.

There had been comparatively few of 'B2 back for their 45th, and North Fayerweather sufficed to hold them without crowding. It had been 'B7 that took the cake as always—for '*B7 had won the Class of '94's reunion cup every time it had had the chance, and now had repeated the feat once again. Maddox was glad of it, for he had always liked 'B7. It seemed to him one of the most notably loyal classes he had ever seen. The headquarters had been in South Massachusetts—and easily the most picturesque figure throughout the week-end was Dr. Charles A. Eastman, genuine, honest-to- goodness Sioux Indian, with the most gorgeous of war-bonnets trailing like clouds of glory as he walked—or rode, for the doctor bestrode a wicked mustang now and then.

There had been less interest for Maddox in the other "reunioners," to accept the Daily Dartmouth's cumbrous name for them. There was Oughty-Two in Middle Mass., 1907 in Wheeler, 1912 in Hitchcock, 1917 in Topliff, 1922 in Middle Fayerweather, and 1924—a few out of so many—in Reed. Maddox could tell you where Reed Hall was, but he would have flunked miserably if asked to locate Hitchcock or Topliff. Oldtimers need guides in Hanover these days.

As ever, Commencement had struck its real stride in the last two days. Monday, sacred to ball games, alumni meetings and such, was one of the finest days Maddox remembered from the standpoint of weather. To be sure, the projected ball game missed fire the first time because the Vanderbilt team had missed connections somewhere up-country and didn't come into town until afternoon; but there were three innings of scrub playing in the forenoon, in which Jeff Tesreau showed what he could and couldn't do at first-base. Maddox wondered if this imperilled any one's amateur status, but guessed not.

Then in the time of lengthening shadows came the real game, closing a baseball season not too successful with a belated victory in which it was asserted errors by the enemy played the predomi- nant part. This sport sufficed to draw away some attention from those pro- foundly contemplative gatherings, the Alumni "Association and the Phi Beta Kappa, which had met at 2 and 4 o'clock respectively; but each managed to trans- act its appointed business with mingled despatch and good humor. Maddox blushed again as he thought of his gold key—won without half trying in a day when Phi Betes were rather automatically made, but carrying just as much of "honors, privileges and signal obligations" as if it had to be worked for as those keys have to be now.

Monday had drawn to its close with fraternity reunions—were these still an unmitigated bore to the active chapter? Maddox suspected they were, well remembering the remote past, but admitted their pleasures to the doddering oldsters who wandered in, renewed acquaintances with each other, and sipped innocuous punch. Then an evening of music by the College organizations, including both the Glee Club and that indefatigable band, which had performed so willingly throughout and which so ably supplied the place once filled by the melancholy Mr. Nevers and his hired players of the elder years.

And now it was the night of a crowded Commencement day. It was all over. The tumult and the shouting had died— or nearly so—with the Alumni dinner. Only those belated revellers down below were still announcing to the stars that, seated by a metaphorical fire, they defied frost and storm. Maddox wondered if they ever slept, or let anyone else sleep? The 158 th Commencement of Dartmouth College! There had been men present who had seen surely 60 of that series— perhaps more than that, for men live to be well over 90, and Maddox had by no means forgotten dear old Judge Cross.

Looking back on the more recent hours, in which something like 344 black- gowned seniors had received their degrees amidst applause, Maddox found little incidents standing out with more prominence. He wondered if he had really liked the President's academic Tam-o'-Shanter as well as -the old-fash- ioned mortar board. It was different, anyhow, and it had an Old World tang that was intriguing. Did one really rel- ish that line in Hovey's Dartmouth Song —now officially the anthem of the Col- lege—which attributes the extraordinary phenomenon of hill winds in the veins to the sturdy sons of the Alma Mater? Might it not be changed somehow, keep- ing the general idea but conforming to the canons of anatomy? He hoped so.

The great figure among the honorary degree men had been, of course, the ven- erable George F. Baker, notable giver to the cause of education everywhere, but held in especial honor by Dartmouth because of the new Library already rising in the rear of Butterfield and the Col- lege Church. Mr. Baker received the plaudits of a heartily enthusiastic audi- ence, both at the Commencement and at the alumni dinner which followed. Fine that a man of his years and his great possessions should be moved to such worthy bestowals as have marked the very recent times both at Hanover and at Cambridge—to mention no more.

One might perhaps wish that the for- mulae for bestowing these academic guer- dons could be shortened just a trifle— made no less pithy, but concentrated a bit—with an eye single always to the stateliness and dignity of a great aca- demic festival. The ideal introduction of a candidate for degrees bestowed honoriscausa had always seemed to Maddox to call for a past-master of epigraphy. Hoppy—for one always though of him as Hoppy—did it well; most extraordi- narily well. None the less there might be even more effectiveness with a strong- er insistence on compression.

As for the men selected for the honors of that sort, they had seemed unusually well chosen, doubtless out of a great field of possibilities every candidate in which had. strenuous backers. The honorary degree, being America's nearest approach to a patent of nobility, Maddox had heard was being eagerly sought on behalf of hundreds more than all the American colleges could honor in that way. Well enough to keep the numbers down, to the end that such degrees retain their prestige!

Drowsily, for sleep was drawing near at last, Maddox ran over in mind the list of distinguished personages over whose heads the waiting academicians had passed those parti-colored hoods— rather as if lassooing them. A fine body of men—fine body of seniors—fine old college—158 th

Maddox slept.

The Forty-Year Class (Winners of the Cup for the fourth time)

The Twenty-Year Class

Features of the '87 Reunion Stanley E. Johnson and Charles E. Eastman in regalia

The Ten-Year Class

The Trustees and Guests of the College

The Seniors in line for the Commencement procession

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICIAL FITNESS V.

August 1927 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D., -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1927 By J. R. Chandler '98, Clarence G. McDavitt '00 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES HOLD MEETING IN HANOVER

August 1927 By Hanover, N. H.,, E. K. Hall -

Sports

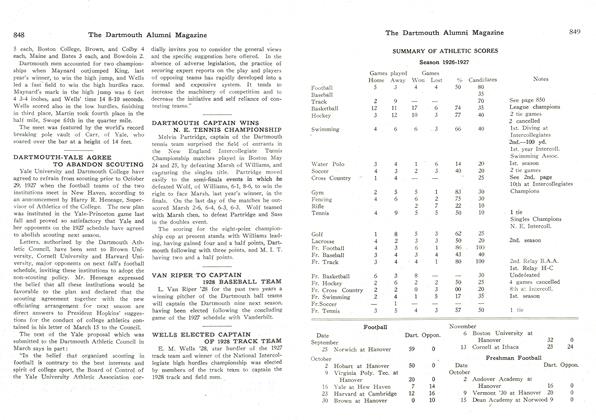

SportsSUMMARY OF ATHLETIC SCORES

August 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

August 1927 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

August 1927 By Herrick Brown

Article

-

Article

ArticleMORNING SESSION

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

February, 1924 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH GRADUATES FORM FLORIDA ALUMNI ASSOCIATION

May, 1926 -

Article

ArticleDEAN W. R. GRAY '04 ELECTED LIFE TRUSTEE

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

ArticleGlee Club Trip

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleThe Plan: To Plan More Plans

FEBRUARY 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92