1. Athletes2. Class Work, 1926-7—First Semester

Medical Consultant in Nutrition and Physical Fitness, Dartmouth College

This is the fifth in a series of reports on physical fitness work at Dartmouth College. The earlier articles can be found in the Dartmouth ALUMNI MAGAZINE for February, May and November, 1925 and December, 1926.

1. ATHLETES

In the fall of 1924, I was consulted by Coach Hawley in regard to the physical condition of the Dartmouth football team. He remarked, "If you can possibly help prevent the team's going 'stale' it will solve our chief difficulty because no matter how well the team is trained or how much football they know, if the men go 'stale' the game is lost. This problem of staleness is my great worry, especially as we have a hard schedule of major games this year, including Yale one week and Harvard the next, and ending up with a long trip to play the University of Chicago.''

I replied that I would watch the team for a time and make such suggestions as would be likely to help keep the men in an optimum physical condition and possibly I might be able to find the cause or causes of their going "stale". Accordingly, I checked up the daily program of these athletes, their food and health habits and found their "health intelligence quotient" to be 75%, a higher average than that obtained from any other group yet tested.*

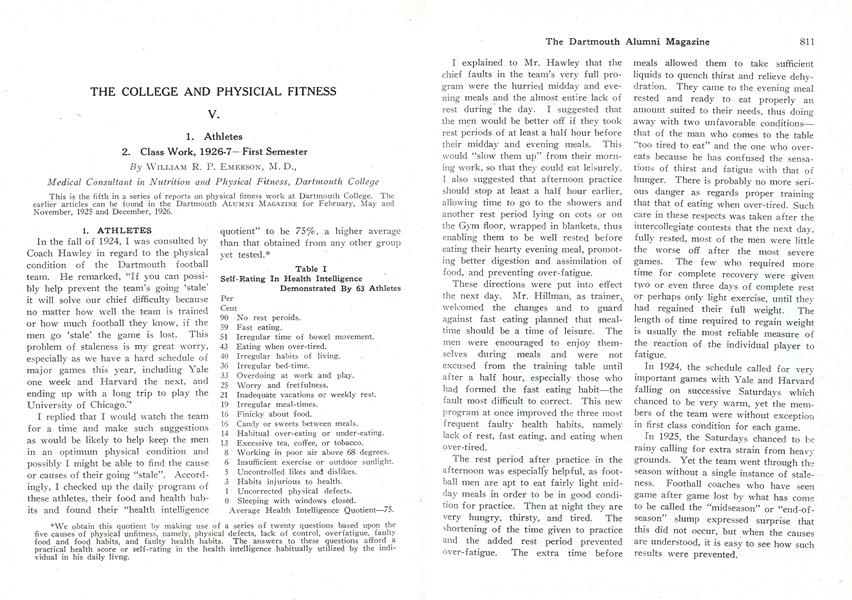

Table ISelf-Rating In Health IntelligenceDemonstrated By 63 Athletes Per Cent 90 No rest peroids. 59 Fast eating. 51 Irregular time of bowel movement. 43 Eating when over-tired. 40 Irregular habits of living. 36 Irregular bed-time. 33 Overdoing at work and play. 25 Worry and fretfulness. 21 Inadequate vacations or weekly rest. 19 Irregular meal-times. 16 Finicky about food. 16 Candy or sweets between meals. 14 Habitual over-eating or under-eating. 13 Excessive tea, coffee, or tobacco. 8 Working in poor air above 68 degrees. 6 Insufficient exercise or outdoor sunlight. 5 Uncontrolled likes and dislikes. 3 Habits injurious to health. 1 Uncorrected physical defects. 0 Sleeping with windows closed. Average Health Intelligence Quotient—75.

I explained, to Mr. Hawley that the chief faults in the team's very full program were the hurried midday and evening meals and the almost entire lack of rest during the day. I suggested that the men would be better off if they took rest periods of at least a half hour before their midday and evening meals. This would "slow them up" from their morning work, so that they could eat leisurely. I also suggested that afternoon practice should stop at least a half hour earlier, allowing time to go to the showers and another rest period lying on cots or on the Gym floor, wrapped in blankets, thus enabling them to be well rested before eating their hearty evening meal, promoting better digestion and assimilation of food, and preventing over-fatigue.

These directions were put into effect the next day. Mr. Hillman, as trainer, welcomed the changes and to guard against fast eating planned that mealtime should be a time of leisure. The men were encouraged to enjoy themselves during meals and were not excused from the training table until after a half hour, especially those who had formed the fast eating habit—the fault most difficult to correct. This new program at once improved the three most frequent faulty health habits, namely ■ lack of rest, fast eating, and eating when over-tired.

The rest period after practice in the afternoon was especially helpful, as football men are apt to eat fairly light midday meals in order to be in good condition for practice. Then at night they are very hungry, thirsty, and tired. The shortening of the time given to practice and the added rest period prevented over-fatigue. The extra time before meals allowed them to take sufficient liquids to quench thirst and relieve dehydration. They came to the evening meal rested and ready to eat properly an amount suited to their needs, thus doing away with two unfavorable conditions that of the man who comes to the table too tired to eat' and the one who overeats because he has confused the sensations of thirst and fatigue with that of hunger. There is probably no more serious danger as regards proper training that that of eating when over-tired. Such care in these respects was taken after the intercollegiate contests that the next day, fully rested, most of the men were little the worse off after the most severe games. The few who required more time for complete recovery were given two or even three days of complete rest or perhaps only light exercise, until they had regained their full weight. The length of time required to regain weight is usually the most reliable measure of the reaction of the individual player to fatigue.

In 1924, the schedule called for very important games with Yale and Harvard falling on successive Saturdays which chanced to be very warm, yet the members of the team were without exception in first class condition for each game.

Tn 1925, the Saturdays chanced to be rainy calling for extra strain from heavy grounds. Yet the team went through the season without a single instance of stateness. Football coaches who have seen game after game lost by what has come to be called the "midseason" or "end-of- season" slump expressed surprise that this did not occur, but when the causes are understood, it is easy to see how such results were prevented.

Among these 63 athletes whose health was checked up before the season was well under way were ten members of the football team who were again checked up at the cldse of the season. The exact self-rating of these men before and after receiving instructions was as follows:

Comparing faulty health habits before the training season (Table II) and after (Table III), it will be noticed that at the end of the season there was a perfect score on thirteen of the most serious health habits. Some of the faulty habits could not be corrected as it was in some instances impossible for the player to do so because of circumstances not under his control. During the period of examinations late hours seemed necessary to some men. Other men were working as waiters and fast eating and over-fatigue were especially difficult to correct.

The result of the correction of faulty health habits together with the good judgment of Mr. Hawley and Mr. Hillman was that not a single man went"stale" during three whole seasons and at the end of each season the men were in such condition that they were quite ready to enter other major sports, five doing so without evidence of over-strain, which demonstrates that it is not the sport itself that causes staleness but faulty training. That these men were able to keep in such fine condition is the more remarkable in that a considerable proportion of them were not only leaders in college life but also stood high in scholarship. From the first, second and third teams a single team could have been made up with every position covered by men with Phi Beta Kappa standing. Therefore, this was a demonstration that football of itself should not interfere with a man's doing good work in his studies if he trains properly. A student can enter any sport without harm if he knows when he is over-training and will keep within safe bounds-. The younger the individual the greater the care that should be exercised.

Another important point is that men in the best condition are less liable to receive injuries because they are more alert mentally and their bodies respond more quickly to each demand. A fraction of a second's time may make the difference between an accurate play and a fumble or missing a tackle.

It is interesting to note that the zeal of these football men to excel had led them at first to make errors as regards over-fatigue (over-doing and eating when over-tired), thus reducing their average to 67 as compared with the 75 of the larger group, but this same zeal led them to improve their score to 92. That is, they increased their health intelligence quotient 25 points.

The principles of training for adequate physical fitness are the same whether the person in training is underweight and needs to be brought up to meet the requirements of an ordinary day's living or an athlete who will be called upon to deal with extraordinary conditions in football or some other sport. In either case it is necessary to see to it that one's supply of energy and strength shall be more than equal to the demands made upon it and that there shall be a balance on hand and quick recuperation following any special expenditure of energy and not a constantly increasing deficit of physical resources. In either case the problem is individual but the general lines of training are the same. Thus, in the case of one who is underweight, the first requirement is to find the causes and see to it that they are removed. Even when physical defects have been attended to, faulty health habits may lead to disastrous consequences. Thus, a person who gets up late in the morning with- out allowing sufficient time to start the day right, rushes through an inadequate breakfast, has no time to attend to nature's demand for a bowel movement, hurries to „ classes or work, bolts his lunch at one hour one day and at another the next, finds it impossible to get down to work in the afternoon without great effort, eats too little or too much at the evening meal, feels restless in the evening and seeks diversion in a badly ventilated hall or theatre and goes to bed at an irregular hour, should not expect to be in the best physical condition nor should he expect to be able to do his best mental or physical work. Yet, how many are following daily almost exactly this program, and are wondering why it is so difficult for them to study and why they are not successful athletes.

2. CLASS WORK 1926-7First Semester

Candidates for admission to Dartmouth last fall were given instructions in the Spring with reference to training to be carried out during the Summer in order to begin college work in September physically fit. The reports this year were somewhat more detailed than those made for members of the Class of 1929 and it was found that the best progress was accomplished by the men during the period before the close of school in June. It is very evident that it is more difficult for them to make progress or even to hold weight during the Summer, especially when they are actively engaged in some occupation and are at the same time concerned in meeting the demands of social life. Under ordinary conditions, students who are free from physical defects can make progress on the basis of our program but the special emergencies of Summer call for definite training in health habits. The success of what Dartmouth has undertaken in these lines is remarkable but there is great need that ths same standards and program should be introduced into preparatory schools so that an earlier start may be made.

The results of a "health intelligence test" given to 352 Freshmen in 1925, are shown in Table IV.

Fast eating, lack of rest periods and eating when over-tired are the most common of their faulty health habits. When the men realized the prevalence and significance of these defects many responded at once and gave evidence of improvement. The college administration had already undertaken to prevent fast eating in the Commons by regulating the service of meals and by providing music at meal time. A check up made in 1924, showed for eighty men an average time for breakfast of 12.4 minutes, for dinner 15.4 minutes and for supper 16 minutes. The range of time for the eighty sudents was from seven to twenty-four minutes. One of the supervisors who has been on duty for seven years remarked, "We have a different lot of men this year. We can't get them to hurry."

An inspection of the items in the table shows that 11%—39 men, had the candy or sweets habit; 5%—18 men, had entered college with known physical defects uncorrected; and 2% were still sleeping with windows shut. Yet this low score compares favorably with those found in other situations, as, for example, we found 8% of the members of a senior class in a medical school sleeping with closed windows. From the studies we have made it would seem that the more years spent by students in school, college and professional schools the lower are their scores in health intelligence!

When we turn to the actual work with the students it is most gratifying to find that this third year of our work at Dartmouth has shown even a greater demand for health diagnosis on the part of the students and a larger number have attended classes than in previous years; Nearly four hundred men, about 20% of the whole college, have come in for consultation and advice and 171 have followed regularly the physical fitness program. When the results on the weight charts are totalled and averaged—including alike those who have trained w'tb the greatest care and others who have neglected many important rules—it is found that from the opening of college to the end of the first semester the men have averaged four and three quarters pounds gain. When attention is turned to the more successful we find that the fifty "best" men averaged twelve pounds during that period. There were ten who ran their average up to more than six- teen pounds in seventeen weeks—five of them ran over eighteen and one man cleared twenty-nine pounds—almost a pound and three quarters each week that he had been in training!

This leader in gaining weight is a senior who said, "For three years I tried to gain but did not know how." He found as a result of a health diagnosis that he was physically "free to gain" and that the health habits to which he needed to give immediate attention were (1) omitted and inadequate breakfasts, (2)- late hours of study, irregular bedtime, and lack of rest, (3) excessive use of tobacco. Correction of these defects led to prompt improvement and an excellent state of physical and mental fitness.

The results during the first two months of the year are very satisfactory for most of the students in our classes. There are .a number who have uncorrected physical defects and cannot be expected to gain until their parents, family physicians and themselves have got to the point of health intelligence necessary to carry out the needed surgical and medical treatment. The real test of character appears for the greater number, however, in connection with the problems discussed more fully in previous numbers of this report—examinations, "big games," vacations, carnivals, competitions for fraternities and other extracurricular activities. As the year goes on a line of cleavage appears with much distinctness between those with marked development of "control", on the one hand, and the less stable group who become victims of the various demands of college life, on the other. This latter type shows sagging weight lines when these occasions of special stress arise. Thus, seventy-three men in the freshman class for the first two months gained at a rate of what would amount to more than forty pounds a year but a considerable group fell to only a fraction of this achievement as soon as real difficulties appeared.

Nearly half of the men lost weight during the Christmas vacation. A tenth of them lost on an average more than three pounds in this time. There seems to be an indication that more of the holiday loss this year was due to work for the purpose of earning money than has been the case in past years. Last summer an unusual number of students failed to hold their earlier gains because of failure to keep up training when at work.

We. have been pleased to have so many sophomores insist upon reporting for checking up on the training program. They have held their own as the difficulties of the college year increased better than have the freshmen but have averaged two pounds less during the semester than the representatives of the first year class.

It is a satisfaction to observe in the Carnival and other contests that men who have insisted upon holding themselves to optimum standards ■ carry off the highest honors. At a meet held recently, one of the victors remarked, "It was the extra pounds that did it!" Mention has been made of the) athletes who learned to come through strenuous games and seasons in optimum condition. One of them, a star player and captain of the second sport he had taken up following the close of the football season, remarked, "I wish I had gone out for baseball also for I can do so much better in college work when I have the exercise and regularity that goes with training."

While credit is given for our physical fitness work in place of required recreation. it is, however, entirely voluntary. Men come of their own will for conference and health diagnosis and are at liberty to change back to recreation if they choose to do so. Yet only an occasional man has given up our program once he has undertaken it and then because he had been carried away by a cles're to get into some athletic contest regardless of whether he was in "fit"' condition or not.

In carrying on the work with both freshmen and sophomores in physical fitness classes we have utilized to great advantage as instructors, juniors and seniors who have excelled both in athletics and in college studies. Thus, the college teaches itself.

During our work here at Dartmouth for the past three years, an increasing number of men have remarked, "I think that I can increase my health intelligence sufficiently to accomplish"—this or that undertaking. These men realize that health is not a matter of fate or of accident but one of cause and effect. The higher the health intelligence the better the health and, conversely, the lower the health intelligence the poorer the health. Thus, a man's score becomes his challenge and he appreciates the fact that it is "a man's job" to become and continue physically and mentally fit.

*We obtain this quotient by making use of a series of twenty questions based upon the five causes of physical unfitness, namely, physical defects, lack of control, overfatigue faulty food and food habits, and faulty health habits. The answers to these questions afford a practical health score or self-rating in the health intelligence habitually utilized by the individual in his daily livng.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S 158TH COMMENCEMENT

August 1927 -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1927 By J. R. Chandler '98, Clarence G. McDavitt '00 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES HOLD MEETING IN HANOVER

August 1927 By Hanover, N. H.,, E. K. Hall -

Sports

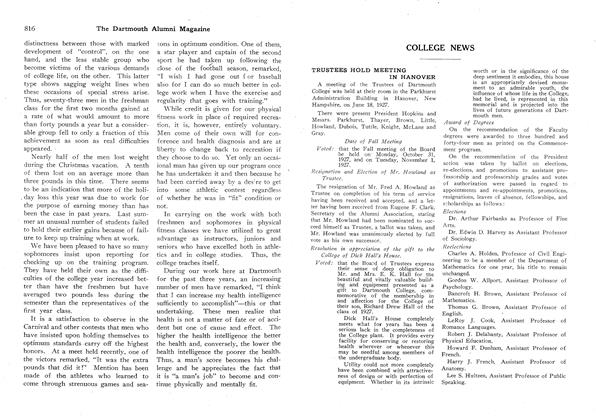

SportsSUMMARY OF ATHLETIC SCORES

August 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

August 1927 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

August 1927 By Herrick Brown