"The Poet-Saints of Maharashtra, #3 Bhikshegita the Mendicants Song. (The story of a Converted Miser) a translation of the 23rd Chapter of the Eknaphi Bhagavata," by Justin E. Abbott '76, has recently been published by the Scottish Mission Industries Company, Poona, India. Copies of the book may be obtained from Dr. Abbott at his home in Summit, New Jersey.

"Tolstoy," a play in seven scenes by Henry Bailey Stevens '12, which ran serially in Unity, has been published in book form by T. Y. Crowell Company.

"Ruskin's Process of Education," by Jason Almus Russell '20, appears in the September and October issues of the Progressive Teacher (Morristown, Tennessee).

A poem, "The Lecturer at the Club," by Marshall Schacht '27, was printed in the Boston Daily Herald, May 28, 1928.

The Red Boole for October, 1928, contains a story, "Business is Pleasure," by Elsie Janis and Gene Markey '18. Mr. Markey, in collaboration with Charles Collins, is the author of a novel, "Dark Island," published by Doubleday, Doran.

An article, "Rollins Conference Plan in Action," by Professor E. O. Grover '94, appeared in Progressive Education Magazine for July. This article is based on an address given by Professor Grover at the Progressive Educational annual convention last March in New York City.

Charles F. Eichenauer '05 fs the author of an article in the August issue of the NationalPrinter-Journalist, entitled "Four Slickers Eye 1-Newspaper Towns."

The September issue of Plain Talk contains an article by Dr. W. Beran Wolfe '21 entitled "Anyone Can Have a Complex."

The August issue of the North AmericanReview contains an article, "Newspaper Paralysis," by George Spargo, ex '24.

The H. W. Gray Company, New York publishers, have recently issued the following numbers, the musical composition by Hugh A. Mackinnon 'l4: "Ballad of Saint Stephen," Carol for Voices; "I Sing of a Maiden," Carol for Voices; "I Saw Three Ships," Carol for Voices; "This Endes I Saw a Sight " Carol for Voices.

Russell Rhodes, '18, former American Vice Consul at London, England, is the author of an article entitled, "How British Banking Differs From Our Own," published in the July issue of The Financial Digest in which he discusses the history and development of famous old London banks, such as the Bank of England, Barclay's, Child's, Coutts', Lloyd's and others.

In the September issue of The FinancialDigest appears another article by Mr. Rhodes on "The Story of Lloyd's in London," dealing with the marine insurance activities of the world-famous firm of underwriters.

Equity, the magazine published for members of The Actors' Equity Association, contains in its August issue an article by Mr. Rhodes on the late Dame Ellen Terry.

Mr. Rhodes is also a frequent contributor of feature articles to The Hartford Courant,The Boston Globe, and The Springfield Republican and has written several book reviews for The New York Sun and The HartfordTimes.

BACK OF WAR. By Henry Kittredge Norton, 1905. New York: Doubleday,

Doran Company, 1928.

The high excellence shown by this author in his previous books brought the present reviewer to Bach of War with keen anticipations. Nor were these expectations disappointed. Mr. Norton again displays a wealth of concrete facts with which to substantiate the discussion of many intricate problems which have an international range and are inherent in a work dealing with the conflicts of a world whose integral parts are shown at length to be wholly interdependent. As has been said, "He gets at the roots of international disputes in a way that makes them understandable, dissects war and lays bare the forces which must be overcome before lasting peace is to be established."

Perusal of the book reveals discussion by a mind familiar with the comparative method of study and that of historical sequence. This gives one confidence in the author's conclusions. Those who look for panaceas that will heal all human woes will, however, be disappointed. The forces at work causing or preventing wars are too vast to be resolvable by simple formulas. Mr. Norton evidently has no brief for pacifism or militarism as such, hence his book is calculated to offend the dogmatists in either camp. Yet they should read it. To those men who bear the burdens of citizenship and of life cheerfully and ungrudgingly, to those men of goodwill and of greater good sense, who take the world nearly but not quite, as they find it, the author offers much challenging thought.

The causes of war among primitive men are dealt with under the headings of plunder, land-necessities, conquest, honor and revenge. Salient among ancient and medieval stimuli to conflict have been dynastic ambition, racial rivalries, religious intolerance, patriotism, and more recently national self- determinism. The economic spurs to antagonisms have arisen from the necessities of the food supply, from intermittent pressure arising here and there out of an unregulated increase in population, from national jealousies and chicaneries connected with shipping and tariffs, and from restricted output of raw materials for which there is more than a national demand. The impulses of national vanity for colonial dominion also incite to international unrest but are sanely shown to be indissolubly linked with the necessities of a never-ending supply of raw materials reaching the industrialized nations of the West. No group of statesmen could continue in office whose measures and dealings with other nations concerning this supply should be inept. Hence, the provocation to misunderstanding and war; hence, the frequent brow- beatings of weaker nations by the strong. This is nationalism whose strong and weak points are nicely evaluated. But nationalism easily led to imperialism which, according to the author, exhibited predatory, strategic, administrative and financial phases. He exactly appraises this imperialism; knows its services and disservices and its dangers to the common life of humanity. He sets forth his analysis with a plethora of illustration and incisive comment. For example, he shows how in China a much-needed, foreign-imposed, administrative imperialism is vitiated and nullified by an inexcusable and antecedent predatory one.

Not the least informative portion of the book is that in which problems of every national group without exception are grappled with. Thus the tasks confronting the people of the United States, of the British Commonwealth of Nations, of France, Italy, Germany, Russia, and Japan, are trenchantly discussed; while under the caption of "Regional Problems" those of the Balkans; of Northern, Central and Eastern Europe; the Mediterannean region; the Near and Far East; South America; Mexico and the Caribbean are no less competently handled.

The two preceding paragraphs are nothing but a slightly expanded table of contents. Beyond suggesting the reach of the author's mind they do little to set forth the acuteness of his insight, the closeness of his reasoning, and the balance of his judgment. Insight and balanced judgment are among the rare and valuable mental gifts. Sound reasoning comes only from severity of mental discipline. We will let the author's own words illustrate these qualities.

Concerning the mind and temper of the American people, a mind frequently marked by high idealism, Mr. Norton speaks of its dual quality of pacificism and warlikeness. He says, "the desire for peace is the outstanding characteristic of the American people ... it by no means follows that Americans as a people are pacifists, if by pacifist we mean a believer in peace at any price. The fact that the nation has been aroused to make war on an enormous scale four times in the last century demonstrates that there are issues for which the American people will fight. After each of these struggles there has been a surge of pacifist sentiment which has made itself effective to the extent of diminishing the military establishment and leaving the country in a state of unpreparedness for the next war."

When he considers the same qualities in the larger human group, the same soundness is shown. He writes, "The vast majority of mankind, even among the so-called warlike nations, probably do not fight for the love of fighting; they fight to gain an end, to secure their needs, or to satisfy their desires." Here he shows awareness of the fact that men must live, that it is difficult to do so, and that the first duty of an in-group is to itself alone. But this as hinted above leads to nationalism. Concerning this derivative he has much to say; "There seems to be a strange fatality about nationalism which, the moment it is successful makes it a fruitful source of further international dispute." Yet, "if we attempt to analyze patriotism (we find) that the unwavering cooperation of the group has been a necessity for its preservation and development. In a world where a group was theenemy of all its neighbours, a group in whicha substantial number of the people began tophilosophize about permanent peace and international justice and thus bred and turned them-selves into 'conscientious objectors' wouldsoon have been eliminated So long as the normal state of the world was war, and to the extent that the same war psychology prevails to-day, group cooperation is essential to group preservation. Any nation, even in our own time, that chooses to ignore the realities of the world in which we live and, resolving that war is evil, should refuse to resort to war, under no matter what circum- stances, would simply invite conquest andelimination and thus assume a large measureof responsibility for allowing civilization toslip back to where war was the normal condition." (Italics are reviewer's.)

But the by no means indicates that the author has one-sidedly fallen into the "trap" of militarism. For he also shows how the peace group has widened by our times; how democracy and its fundamental driving forces have done away with much of the capricious and irresponsible handling of war by individuals and cliques. In advanced states, "the leader must defer to the people and there the military elements have been subordinated to the civil." "In primitive society but slight incentive was necessary to provoke bloody reprisals while in modern times war psychology is not necessarily the result of deliberate attempt on the part of any person, but rather a spontaneous growth having its roots in innumerable persons, interests and events." Those who recall the course of events in the United States during the years from 1914 to 1917 will sense the cogency of this reasoning. Only after repeated provocation, large losses and threatened larger ones, and after the exercise of great patience was the mind of the people of the United States transmuted into an awakening, a determi- nation resolutely to safeguard its interests and to defend that social stability of American civil life, without which the life of man any- where tends to run down into the miseries of uncivilization.

Such then is a sampling of illuminative discussion to which the attention of the reading public is called. It seems ungracious to ask that the book should be equipped with an index and a bibliography. Yet the number of suggestive interpretations and pithy sayings scattered through its pages is large and makes one wish for their help. One desires especially to share more fully the sources, the richness of which becomes apparent in the reading of the book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThis New Library

November 1928 By Henry B. Thayer, '79 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate and His College

November 1928 By President Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1914

November 1928 By John R. Burleigh -

Article

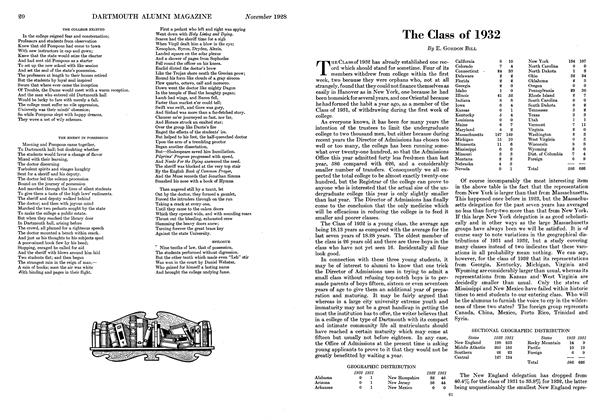

ArticleThe Class of 1932

November 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Lettter from the Editor

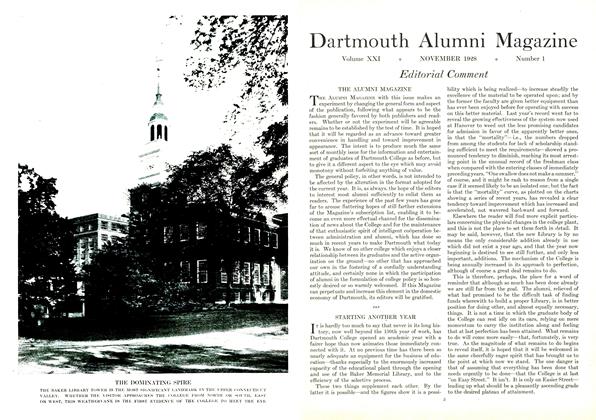

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

November 1928 By Charles D. Webster, Air Reduction

Books

-

Books

BooksProfessor James Mackaye is the author of "The Dynamic Universe" published

February, 1931 -

Books

BooksSOCIETY AND CULTURE.

JULY 1965 -

Books

BooksTHE LITERARY ART OF EDWARD GIBBON.

June 1960 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHE RECOVERY OF GERMANY

MARCH 1930 By G. R. Crosby -

Books

BooksENGINEERING: ITS ROLE AND FUNCTION IN HUMAN SOCIETY.

JUNE 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS.

NOVEMBER 1967 By MAJOR ERIC H. WIELER, USMC