Francois Denoeu. Visiting lecturer in French. (Storrs' Bookstore, Hanover.)

"The fire-eyed maid of smoky war," the goddess of Hotspur, is stripped of her divinity and of her virtue by Professor Denoeu in this dramatic story which everyone who wants to feel trench life in the World War will do well to read and ponder deeply. Here is no survey of disquiet on a 300 kilometre front, no attempt to bid a commercially successful farewell to arms, no fraudulent use of cinema-horrors as a curtain behind which to lay down a barrage of appetizing amorous adventures. No one soldier knew the entire front. What each did know was his own platoon, a few officers, a score of quiet sectors, half-a-score of corners of major battlefields. This book is the story of the platoon in which Professor Denoeu was a lieutenant, eloquent because it is so obviously true, because it holds tenaciously to the terrain his body touched, because it was written during the occupation of the Rhinel'and before 1920, while the pulse of conflict was still throbbing painfully in his brain and throughout his nerves. We cannot have too many of these documents of real experience; they alone will tell the story our children must know, the story some of us will not tell, or cannot tell as M. Denoeu has told it.

Nor is it the story of just his platoon. The very concentration of the focus makes the record burn like a sun glass into the memories of all who were there. For Americans there is the added interest that the author's service exactly spans the history of the A.E.F., as he was called to the colors in 1918. All who were in the Second Division, A.E.F., will recognize "Tinoubliable nuit du 17 juillet 1918," and the terrain, on which the story opens. From the first, one finds American soldiers- and poilus, not as knights in maiden mail, not as cowards and perverts, not as in the lying pages of Dos Passos or Barbusse, but as they were: profane, insouciant, disillusioned, but carrying on.

"La guerre, on ne la comprend bien qu'avec sa chair." For the mind there was no perspective in the labyrinth of the trenches. M. Denoeu recreates the experiences of the senses: fatigue on march, harsh commands grating on the ear, smells of gas, powder, and sewage. Gone from the uniforms are the croix de guerre, replaced by the more familiar wooden crosses driven deep into fresh mounds. Moans of the dyi ng, and voices of the dead. We are always at the front, or near it. No Rose of No Man's Land threads her way gracefully among the corpses with lilacs in her pretty hand. Relief for the reader comes only as it came for the soldiers: a billet a few miles back with drink and sleep for all, a nauseating debauch for some. Death is forgotten for a moment as one writes a poem for himself to read, or a letter full of comforting white lies for the anxious folk at home. Sentiment is choked with a volley of poilu ribaldry (omitted from dictionaries, but euphemistically translated in a special glossary for English readers).

With the objective sound-picture goes a fascinating close-up of human nature, principally in the person of Hubert: a youth in love with life as well as his country, distrustful of the formal functions of church and state and general staff, trying to wage war and be humane at the same time! This ghastly paradox is depicted with stark candor over and over, as in the case (pp. 301-4) of the ambushed German whom Hubert can and should (?) kill out of hand, whom he nevertheless spares at the risk of death to self and his own comrades. The alternatives provided no academic question in 1918, nor was there usually time to debate the pros and cotis.

The conclusion is that war is futile and brutal, but not, dear reader, that it is necessarily brutalizing (except to the civilian profiteer). Hubert is killed off and cited for heroism, and cannot testify. But the author is alive and here for us to inspect. Perhaps his perennial gaiety on the, Dartmouth campus is greater because he has seen life where gaiety was exiled. The face of death does not sour one on life, in spite of what some novelists would have us believe; it makes us love life on both sides of the Rhine, and hate war. To keep faith with those who sleep in Flanders' fields, M. Denoeu has written this "histoire trop vraie," dedicated "A mon pere qui a vingt ans fit 70; comme a vingt ans j'ai fait 1918; a mes enfants, dans I'espoir de faire mentir le 'Jamais deux sans trois.' "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

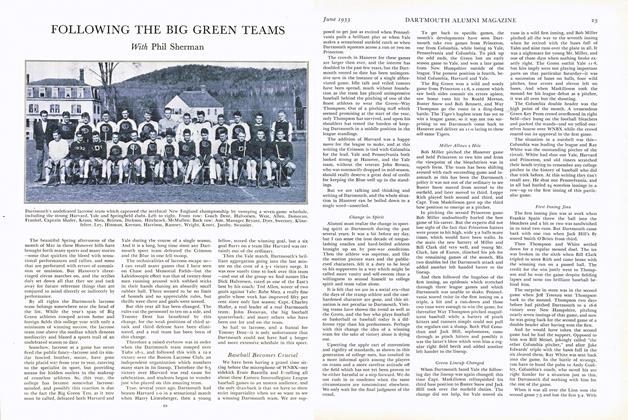

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

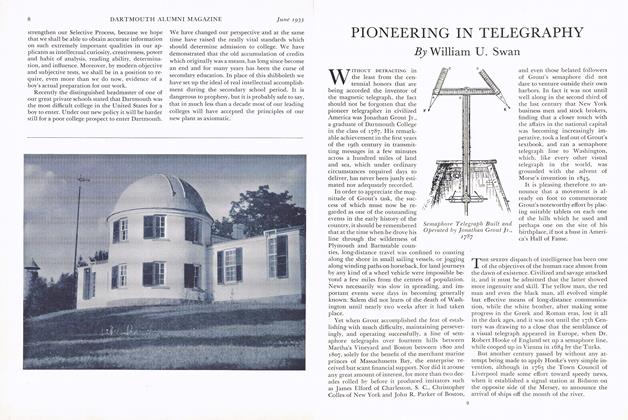

ArticlePIONEERING IN TELEGRAPHY

June 1933 By William U. Swan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of IQ9 1

June 1933 By Jack R. Warwick -

Article

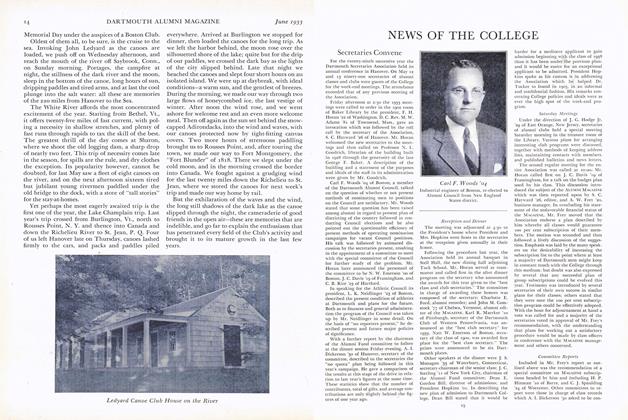

ArticleSecretaries Convene

June 1933

William A. Eddy

Books

-

Books

BooksUNDERCLIFF. Poems 1946-1953.

May 1954 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksBEAU-POIL AU MAROC

June 1940 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksTHE SUPREME COURT AND JUDICIAL REVIEW,

April 1942 By James P. Richardson '99 -

Books

BooksEIGHTEENTH CENTURY STUDIES PRESENTED TO ARTHUR M. WILSON.

NOVEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE MYTH OF ROME'S FALL.

JUNE 1959 By NORMAN A. DOENGES -

Books

BooksCROKER THE TSAR MASTER OF MANHATTAN

June 1931 By W. A. Robinson