THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE with this issue makes an experiment by changing the general form and aspect of the publication, following what appears to be the fashion generally favored by both publishers and readers. Whether or not the experiment will be agreeable remains to be established by the test of time. It is hoped that it will be regarded as an advance toward greater convenience in handling and toward improvement in appearance. The intent is to produce much the same sort of monthly issue for the information and entertainment of graduates of Dartmouth College as before, but to give it a different aspect to the eye which may avoid monotony without forfeiting anything of value.

The general policy, in other words, is not intended to be affected by the alteration in the format adopted for the current year. It is, as always, the hope of the editors to interest most alumni sufficiently to enlist them as readers. The experience of the past few years has gone far to arouse flattering hopes of still farther extensions of the Magazine's subscription list, enabling it to become an even more effectual channel for the dissemination of news about the College and for the maintenance of that enthusiastic spirit of intelligent cooperation between administration and alumni, which has done so much in recent years to make Dartmouth what today it is. We know of no other college which enjoys a closer relationship between its graduates and the active organization on the ground—no other that has approached our own in the fostering of a cordially understanding attitude, and certainly none in which the participation of alumni in the formulation of college policy is so honestly desired or so warmly welcomed. If this Magazine can perpetuate and increase this element in the domestic economy of Dartmouth, its editors will be gratified.

STARTING ANOTHER YEAR

IT is hardly too much to say that never in its long history, now well beyond the 150th year of work, has Dartmouth College opened an academic year with a fairer hope than now animates those immediately connected with it. At no previous time has there been so nearly adequate an equipment for the business of education—thanks especially to the enormously increased capacity of the educational plant through the opening and use of the Baker Memorial Library, and to the efficiency of the selective process.

These two things supplement each other. By the latter it is possible—and the figures show it is a possi- bility which is being realized—to increase steadily the excellence of the material to be operated upon; and by the former the faculty are given better equipment than has ever been enjoyed before for operating with success on this better material. Last year's record went far to reveal the growing effectiveness of the system now used at Hanover to weed out the less promising candidates for admission in favor of the apparently better ones, in that the "mortality"—i.e., the numbers dropped from among the students for lack of scholarship standing sufficient to meet the requirements—showed a pronounced tendency to diminish, reaching its most arresting point in the unusual record of the freshman class when compared with the entering classes of immediately preceding years. "One swallow does not make a summer," of course, and it might be rash to reason from a single case if it seemed likely to be an isolated one; but the fact is that the "mortality" curve, as plotted on the charts showing a series of recent years, has revealed a clear tendency toward improvement which has increased and accelerated, not wavered backward and forward.

Elsewhere the reader will find more explicit particulars concerning the physical changes in the college plant, and this is not the place to set them forth in detail. It may be said, however, that the new Library is by no means the only considerable addition already in use which did not exist a year ago, and that the year now beginning is destined to see still further, and only less important, additions. The mechanism of the College is being annually increased in its approach to perfection, although of course a great deal remains to do.

This is therefore, perhaps, the place for a word of reminder that although so much has been done already we are still far from the goal. The alumni, relieved of what had promised to be the difficult task of finding funds wherewith to build a proper Library, is in better position for doing other, and almost equally necessary, things. It is not a time in which the graduate body of the College can rest idly on its oars, relying on mere momentum to carry the institution along and feeling that at last perfection has been attained. What remains to do will come more easily—that, fortunately, is very true. As the magnitude of what remains to do begins to reveal itself, it is hoped that it will be welcomed in the same cheerfully eager spirit that has brought us to the point at which now we stand. The one danger is that of assuming that everything has been done that needs urgently to be done—that the College is at last "on Easy Street." It isn't. It is only on Easier Street— leading up what should be a pleasantly ascending grade to the desired plateau of attainment.

IS THERE ANY DIFFERENCE?

AT YALE, one reads, the opening year will be marked, so far as concerns at least the three upper classes, by an abandonment of the so-called "honor system of conducting examinations—this change being due primarily to the students' own request. Examinations will be supervised in the old-fashioned way, by faculty proctors.

In the view of the students, who are generally their own sternest critics, the honor system was working badly and merited relegation to the limbo of discarded things. Honor could not be implicitly relied on to prevent cribbing, nor to prevent those who had cribbed from signing mendacious statements that they had "received no help in the examination from any outside source." On the other hand, student conceptions of honor did effectually prevent tale-telling in case cheating were detected by other students—perhaps the most natural, and in one aspect most vital, incident to this whole'experiment. Young men always revolt from giving information against one another. Espionage of a self-starting nature is even more abhorrent than the official espionage involved in the watchfulness of a faculty examiner. Hence the demand for a return to the latter form.

But does it make any real difference? Those who were strictly honorable under the honor system will probably be no less so under the system of faculty supervision-respite the theory of some that the presence of a professor, or proctor, in the examination room is a sort of invitation to cheat him if one can, and therefore makes cribbing a less heinous offence than it would be if one's honor alone were trusted to curb the natural desire to get a good mark by subterfuge. The contention that cribbing would be less flagrantly resorted to if the students were put on their honor seems not to have been sustained.

As presently understood, the Yale experiment retains the honor system for freshmen and for the Sheffield Scientific School. Possibly this will enable comparisons. It may be added, however, that young men with the definite purpose supposed to inhere in one pursuing technical courses destined to fit him for actual professional work are likely to appreciate more keenly than general students usually do the fact that when one cheats in an examination one cheats oneself as well as the professor in charge, and in that measure defeats one's own objects in the search for practical wisdom. What students really want is to know—not merely to pretend to know for the purposes of the moment. That is more easily lost to sight when one isn t studying something designed to fit the student for direct use- fulness in some gainful activity. The honor system would probably work best of all in graduate schools.

If you like the Alumni Magazine in its new dress, show it to your non-subscribing Dartmouth friends. If you have any suggestions, write to the Editor

COLLEGE AFTER COLLEGE

THE commendable custom of mailing to alumni lists of contemporary books which the English department of the faculty regards as especially worth while has been pursued again this summer. It is a species of university extension, useful to many who welcome guidance in the matter of their reading. So many thousand books are now poured out by the presses of the English-speaking part of the world that one desirous of keeping abreast of current thought and current fiction might well despair, in the absence of some efficient clear- ing house to evaluate the worth of books; and while the tastes of readers must often vary from those of English professors in matters of detail, it seems that the recurrent offer of a selected list of the more worth-while recent books should fill what the newspapers usually describe as a long-felt want.

Book-a-Month Clubs are getting to be fairly common in this embarrassed country, where everybody reads and where the meagre time for reading is. absurdly out of proportion to the vast number of volumes available to be read. It should therefore be a serviceable function of the College to extend its ministrations by way of literary suggestion to the scattered graduates, forming what is sometimes called a "College after College" and giving to the alumni one more point of contact with the institution at Hanover.

FREER AND EASIER

ONE feature of the new Library which smacks of a real innovation is found in the series of small reading rooms available for class conferences, at which a less formal attitude than that of a large classroom is made possible to both students and professors. This tends somewhat to gild the pill of education in a way agreeable to both the administrator and the recipient thereof; for in these rooms small groups of men may meet with their teachers, talk freely and easily of the topic they are considering—and smoke, as well. It has been stated further that in the proposed building of the English department, made possible by the generosity of the late Edwin Sanborn, it is intended to maintain a steward, who will, on request, purvey light refreshment when evening classes gather for such seminars. Many of us will experience a pang of regret based on the knowledge that we went to college altogether too long ago. It isn't like anything known in the gay Nineties, surely, when the professor was an awesome personage, inhabiting a remote and cloudy Ida, and with whom few, save only the greasiest grinds, were on anything resembling intimate terms—and those very far from camaraderie.

One perceives in all this a tendency to promote a helpful spirit which will recognize a common interest between teacher and taught, and assist each to a better understanding of the other. It could naturally be overdone—what good thing cannot be? It will be serviceable so long as it really serves the end in view; and the belief is that it may go a long way toward awakening the undergraduate to the comprehension that he is being offered something better than a series of daily chores, on the reluctant performance he depends for his continuance in residence. Chores must still be done—but their aspect may be less repellent if the student can be made to feel that there is a human element underlying them, that the teacher is moved in all parts like himself, and that tasks have some bearing beyond the immediate recitation and the next impending quizz.

FOOTBALL ONCE MORE

Now comes the open season in which football is fair game for all critics. It happens to be a game in which Dartmouth usually excels; and at Hanover it has always been regarded as a sport to cherish for its manifold good qualities, rather than condemn for its incidental defects. Stress has been laid mainly on the danger of overdoing it as a public spectacle—but chiefly because it has been felt that such over-emphasis might threaten the ultimate abandonment of a game which the College, officially, has no wish to see abandoned. That it has been a grand good thing for Dartmouth we believe no one will deny. That it is still a good thing for Dartmouth most alumni will enthusiastically admit. And that it is a feature of the College life which should be safeguarded against abolition seems to us a postulate of President Hopkins's making in which there will be practically universal concurrence. Whether or not the present situation involves over- emphasis of the really menacing kind is open to doubt. This Magazine has inclined to believe that it does not— but isn't far from the point where it would. It is at least clear that alumni sentiment everywhere, in practically every college, would react strongly against any plan to abandon it as an intercollegiate sport; and it is further doubtful that any real majority of professional educators, many of whom are but little sympathetic toward sports in general, would go the length of advocating such a course. The upset of proper college work is admittedly considerable in extent during half a dozen autumn weeks, and some of the more important games are notoriously public shows distracting the mind of both public and the colleges from the true business of education. But—confound it!—we all like it so, and it is sheer folly to talk as if we didn't. The ancients who demanded "panem at circenses" were not unique; they were voicing a durable passion of humanity to have some joy along with the essential.

It is doubtful that anything really needs to be done about it, so long as things go along about as they are going. The obstacles in the way of doing anything are numerous. The alumni, on whose interest every college depends, certainly want nothing done to deprive them of an annual thrill, translatable into revived zeal for the alma mater—whatever one may think of this as a praiseworthy base. Football games of the major grade notoriously finance the whole athletic structure and must be reckoned with (whether we like it, or not) from that angle also. The deficiencies of football may be what you choose, but it is submitted that the benefits far out- weigh them—at least from the Dartmouth standpoint.

THREE PESSIMISTS-HENEAGE, HOPKINS, HAWLEY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThis New Library

November 1928 By Henry B. Thayer, '79 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate and His College

November 1928 By President Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1914

November 1928 By John R. Burleigh -

Article

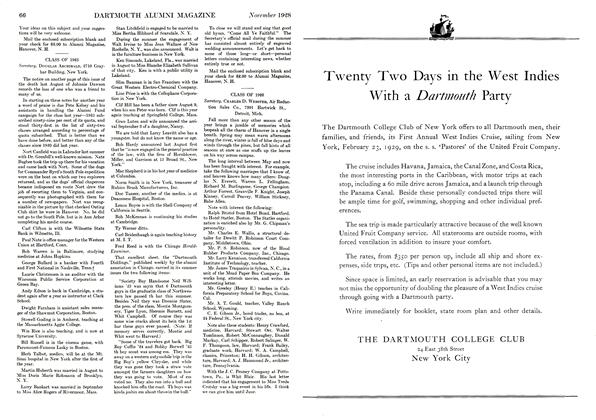

ArticleThe Class of 1932

November 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

November 1928 By Charles D. Webster, Air Reduction -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

November 1928 By Edwin D. Harvey

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMENCEMENT 1924

August 1924 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MAY 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorResponse: The Real Women's Issues

MAY • 1988 By Mary G. Turco