EVER since the first disquieting reports of the condition of Dr. Tucker crept into the public press, the thoughts of Dartmouth men have been insistently directed toward him. The venerable president-emeritus has held the love and esteem of us all to a degree amounting to a wholesome form of hero-worship throughout the years of his retirement from active college management. His status had become almost legendary for those who never saw him but who knew of him as still abiding in the very shadow of the college walls. As a matter of fact, in the recent years, comparatively few, even of those constantly in Hanover. came into personal contact with him; yet his influence was pervasive and his hold upon the sentiment of Dartmouth men was secure. To think of him as gone from us is difficult. He had been so long away. He was gone—and yet not gone.

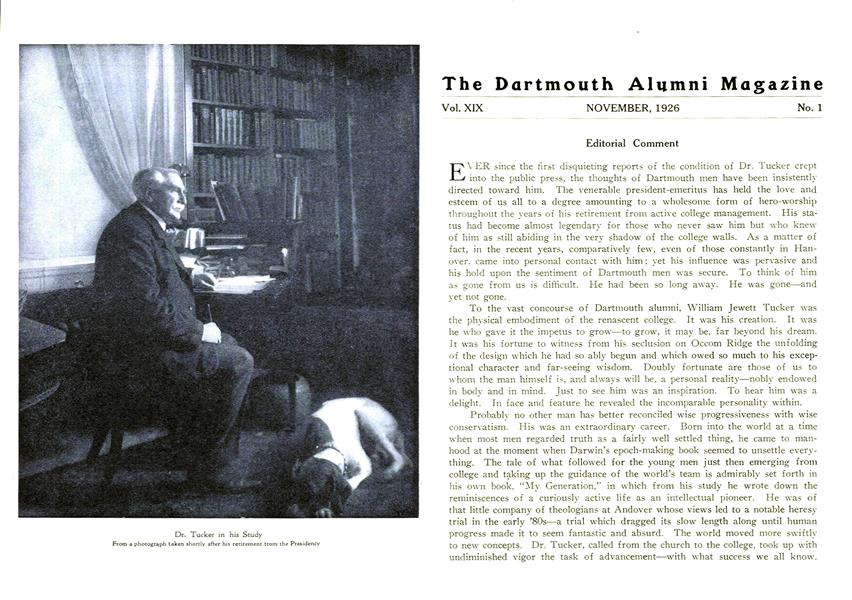

To the vast concourse of Dartmouth alumni, William Jewett Tucker was the physical embodiment of the renascent college. It was his creation. It was he who gave it the impetus to grow—to grow, it may be, far beyond his dream. It was his fortune to witness from his seclusion on Occom Ridge the unfolding of the design which he had so ably begun and which owed so much to his exceptional character and far-seeing wisdom. Doubly fortunate are those of us to whom the man himself is, and always will be, a personal reality—nobly endowed in body" and in mind. Just to see him was an inspiration. To hear him was a delight. In face and feature he revealed the incomparable personality within.

Probably no other man has better reconciled wise progressiveness with wise conservatism. His was an extraordinary career. Born into the world at a time when most men regarded truth as a fairly well settled thing, he came to manhood at the moment when Darwin's epoch-making book seemed to unsettle everything. The tale of what followed for the young men just then emerging from college and taking up the guidance of the world's team is admirably set forth in his own book, "My Generation," in which from his study he wrote down the reminiscences of a curiously active life as an intellectual pioneer. He was of that little company of theologians at Andover whose views led to a notable heresy trial in the early 'Bos—a trial which dragged its slow length along until human progress made it to seem fantastic and absurd. The world moved more swiftly to new concepts. Dr. Tucker, called from the church to the college, took up with undiminished vigor the task of advancement—with what success we all know.

His epitaph might not inappropriately be identical in terms with that of Sir Christopher Wren's. In the New Dartmouth he erected a monument more enduring than bronze.

The young men now coming to Dartmouth are of a generation born into the world since Dr. Tucker laid aside the active tasks of education. For them there is lacking that vivid personal remembrance which is the priceless possession of those who knew the college a score of years ago. Yet these cannot escape the compelling magnetism of his character, which lives in the curious thing, at once intangible and very real, which we call the Dartmouth Spirit. He refounded Dartmouth as surely as Wheelock had initiated it in the wilderness a century and a half before. Because he lived, Dartmouth College is what it is today, and under God ever shall be!

One feels the distressing poverty of common speech to express the uncommon feeling which the passing of such a man inspires. The fitting word is in the heart, but comes haltingly to the mouth and to the pen. Fortunately the word is not needed since it is in the heart of us all. We know what we feelan inexpressible compound of love, loyalty, inspiration and gratitude to a noble Christian gentleman, whose high privilege it was to write himself indelibly into the time in which he lived, and into the future for which he builded perhaps even better than he knew.

ANOTHER YEAR is opening for Dartmouth, with its temptations to say of it the usual commonplaces. The College, we may take for granted, starts its work with all the well known elements which make for satisfaction. It used to be the expected presidental joke, when greeting the Freshman class, that if one might judge by the recommendations which these young men had brought with them there never had been such an assemblage of character and talent before. Presumably with the methods now in vogue for winnowing the more promising wheat from the more unpromising chaff, there is somewhat more of truth spoken in this jest today than was the case some forty years ago.

But this is a magazine for alumni, and it is with the relationship of the graduates to the College that we must feel the most concern. There have been published many caustic comments on alumni interest of late, chiefly to the effect that alumni are likely to be a barely tolerable nuisance. with enthusiasms which would shame an undergraduate in the direction of athletics, but endured by the average President and Fellows because of the money which they bring in. One of the great and growing satisfactions in Dartmouth's present situation lies in the fact that admittedly this criticism does not apply to her. There may be other Colleges where the relationship of the graduate body to the official organization is as cordial, but there is certainly none where it is more so.

Without our fully realizing it, we Dartmouth alumni have been educated into an amazing homogeneous mass, capable of bearing a hand intelligently and helpfully in the work which the President, faculty and trustees are striving to do and what is more, willing and anxious to do it. The great aim and object of this Magazine is to further and to increase both that capacity and that willingness, by bringing nine times a year to the attention of its readers the various problems which arise, and suggestions for meeting them in whatever ways it may seem appropriate for alumni to adopt. In short the doctrine is that Dartmouth is as much "our" college now as ever it was when we were still under its tutelage and its discipline, and that its rising 7000 alumni are actually an integral part of the organization, with a part to play therein, which the administration not only recognizes, but also welcomes.

Nothing succeeds like success, as we all know, and the enthusiasm of Dartmouth men for Dartmouth is the easier to arouse and keep aroused since the progress of the College has been so notable, because in our case there has not to be whipped up that factitious zeal which at its best has a rather hollow ring.

It is not the present purpose to renew protestations against the over-exaltation of superficial and trivial things—such as interest only in the success of the College in terms of the sporting pages in the daily press. All that has been gone over in the past, and the need for it, we like to feel, has very nearly disappeared. There seem to be genuine indications of a pride in Dartmouth as an institution of learning, as distinguished from a place where learning is but incidental to a set of fascinating activities having little or nothing to do with the curriculum. One hopes to keep it so, for it is what suffices to lift Dartmouth alumni out of the ruck at which these irritated commentators are so ready to point the finger of scorn in editorials and articles in the magazines.

The things which are certain to concern us this year in the general line of improving the collegiate equipment will relate almost entirely to the intellectual needs of the College. It may be sadly characteristic of the current epoch that we have supplied ourselves abundantly and first of all with facilities which minister to the corpus sanum; but the fact is we have put behind us the costly business of the gymnasium and athletic field and may therefore turn an undivided attention to various imperative matters which concern the mens sana. The Library, as we all know, is at last on the way to actuality through the generosity of some benefactor as yet unidentified, but possessed of real money and an open hand. At the request of the Trustees, the Alumni Council has authorized and prepared for publication a brief but comprehensive statement of the other necessities, as yet unsatisfied, which we really must take up within the next few years if we are to make our material equipment square with the work to be done and with the numbers we are now striving to serve. The modern Dartmouth must be made a well rounded whole, both in material plant and in an adequately manned staff of instruction, properly paid, properly housed, and capable of being retained.

That last element is important; for in recent years Dartmouth has served to a large extent as a training school for professors who, as soon as they had reached the maturity which would make them valuable, were eagerly snapped up by other institutions in better position to offer salary inducements. It is well enough for Dartmouth to be able to attract promising recruits for the teaching field; but it is also well to be able to keep the recruits whom one has developed into high-grade teaching material. This at present we are not doing.

Comment on that hardy annual, the Alumni Fund, may well be reserved in detail for the period of real activity next spring. It may be proper at this time, however, to note that the autumnal meeting of the Council in Boston took the usual preliminary steps in laying out the work, which for the next year or two will be under the active management of George M. Morris 'll. Early as it is, the engineering work for the campaign is already under way.

For the success of this undertaking there is always required that solidarity on the part of the graduates of the College which lias thus far never failed—and which, we are glad to believe, has become a fixed habit. By it, one tests the reality of our zeal, as something not expressed in sentimental bombast at reunions or at banquets, but in a thoroughly tangible form which really helps. It is the price we pay for the high privilege of counting ourselves Dartmouth men and for seeing the College go from one step of progress to another. More than that, it is the price which we gladly pay, because it is richly worth what it costs us.

In this connection it may not be amiss to renew a suggestion made at various times in recent years that graduates of Dartmouth, even when rather remote, make it a part of their plans to visit Hanover whenever the chance offers. It will be illuminating especially to those whose opportunities for such a pilgrimage have been few and who, while vaguely conscious that the College has grown amazingly, have never actually seen it in its present form. The infrequent visitor cannot possibly appreciate what has been done already, or visualize what remains to do. Besides, there are few pilgrimages which one may make which yield a greater reward. To come back to Hanover whenever one can is to make one a better Dartmouth man, if possible, than one was before. For us in New England such revisitation is easy—sometimes indeed so deplorably easy that we do not come, much as it is true that Charlestown people never visit Bunker Hill monument. For those who live farther away, however, there are occasional business trips, or vacation journeys to the East or to the North, which we believe may with pleasure and profit be planned to include at least a flying visit to Hanover—a town of great beauty at any season, and now admirably equipped to offer a comfortable hospitality.

It is all very well to come at Commencement, but best of all is it to come when the College is in full swing and going about its daily tasks, rather than after its tasks for the year are done and when it is on a sort of a formal dress parade.

Among recent comments in the daily press has been noted a sage suggestion that the colleges of the United States will not really get down to what should be their proper business until the search for higher education recovers from its current state of a popular fad. That is to say, the colleges will be so swamped by the inundation of young people of both sexes, who attend more because it is the fashionable thing to do than because of the slightest interest in "culture," that the pace will be set by such, to the detriment of real scholarship.

It is an old argument and a plausible. Nevertheless we would add a suggestion to the general effect that possibly what the United States requires in its present stage of development is not so much a small body of ripe scholars as a very large body of people who have at least a bowing acquaintance with the things of the mind. It may be prostituting the higher learning to base uses, but we are by no means convinced that it is so. Meantime it is true that with all the world flocking to the colleges there is little or no chance for the exaltation of "culture" as understood by the few and rare minds among every million. It comes to the highly practical question of serving the needs of the moment. If what this country needs is culture—i.e., an intellectual cultivation such as comparatively few among our vast population are capable of attaining—the thronged colleges of the present are not serving, and cannot serve, that need. .We doubt that this is altogether amiss, however, because we suspect the land needs something else very much more, and that the colleges must bend to the service of that need, even if the caustic comment is heard that their graduates seem to bring away comparatively little that stamps them as above the common run in intellectual attainment.

Dartmouth's effort to assess the zeal of the applicant in advance of his admission goes farther than most such efforts in other colleges go in trying to discover how much of a thirst for knowledge such young people really have. It is difficult to measure—perhaps impossible. All that is likely to result is an avoidance of the more obvious misfits, but that is a great deal. We may dismiss as wholly delusive any idea that a college of Dartmouth's size, no matter where it is or what it attempts, can guarantee that a freshman class of 600 young fellows will mean 600 who burn with a holy zeal to become exceptional scholars. If it is the function of an American college to produce such exceptional scholars, it will certainly not be done in prevailing conditions.

But does any one really care ? Do many of us, in other words, seriously wish to go back to the day when only a selected few went to college and enabled by their meagre numbers a nearer approach to the cultural ideal? Very probably there are some who do wish precisely that, or who at least think they do; but it is more probable still that such would be heavily outvoted by those who feel that the present situation, with all its defects, fits better into the American picture in America's immediate situation. One may as well admit that mere numbers do impose a handicap on the ideal of the cultural college and that this handicap will remain until the numbers dwindle. But that need not mean that one should wax hopeless about it, since there are probably compensations.

During the summer there appeared in Scribrters Magazine an article on the comic press as maintained in the American colleges, from the pen of a Cleveland (N. Y.) editor who had been at some-pains to analyze the jests, pictorial and otherwise, which current undergraduate publications of that nature affect. He appears to have been struck by a curious incongruity involved in the conflicting attitudes of mind of the editors engaged in producing the daily newspaper of the student body, and those engaged in pandering to their demand for up-to-date fun. At the risk of misquotation we recall his summary as implying that while the editor of the college daily usually affects to be a sort of high-minded Sir Galahad, the editor of the college Comic gladly poses as one "who would make a sensation even in the profligate court of Charles the Second."

There is more or less truth in this. Whether or not the general run of college boys today reveals a more deplorable liking for the Rabelaisian brands of humor than was to be found among their sires may be doubtful; but there is no doubt that at least the modern taste is more given to flaunting itself without a blush in public. The present generation is prone to do openly what preceding generations did in seclusion—all the way from "petting" at the steering-wheel of the family Ford to printing jests and pictures which even a decade ago would have been regarded as much too daring to venture. The present day scorns to soften its printed profanity with blanks and dashes, although it is doubtless no more given to profanity than was the day that is dead. Morally, one suspects, the student of 1926 is different in no very important particular from the student of 1876—but he takes a different and distinctly more brazen way of revealing his less commendable predilections.

Still, the world has passed through this spasm before. Polite society tolerates much today that would have been a cause for blushes in the Gay Ninetiesbut it is apparently still at some distance from the ribald latitudes permitted without apology or shame in the spacious days of Great Elizabeth. We may have much further yet to go in the extremes of both dress and deportment before we reach the nadir and react. Just now the college Comics seem to delight in being ''off-color" to a degree which not long ago would have been unthinkable—and the daily press of the student body at the same time shows an austerity of idealistic demeanor surpassing what we recall as prevailing in the day of smaller sophistication. Perhaps they offset each other and strike a balance. More probably the joyous and daring abandon now so revelled in by the editors of professedly humorous student papers represents only differences of manifestation between then and now. One recalls the day when off-color literature was furtively bootlegged—and speculates whether or not it was a better day than this in which the same thing is candidly displayed in the market-place and discussed in mixed company.

All of which, let us hasten to say, is not by any means to defend any perverted sense of humor. It is merely to warn those who may not be without sin against casting the first stone. There is much about the college Comics which, without pretending to be unduly prudish, many of us could wish were avoided. It takes a certain amount of genuine wit to elevate what is otherwise mere offensive vulgarity to a more tolerable plane. Not every apostle of the Rabelaisian is a Rabelais; and not every sophomoric emulator of the broad humors of the Decameron is a Boccaccio. Possibly the vogue for excessive daring in this respect rests in some part on the hope that someone is going to be shocked. That does happen.

Dr. Tucker in his Study From a photograph taken shortly after hi. retirement trom the Presidency

The New Cabin at Glencliff

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

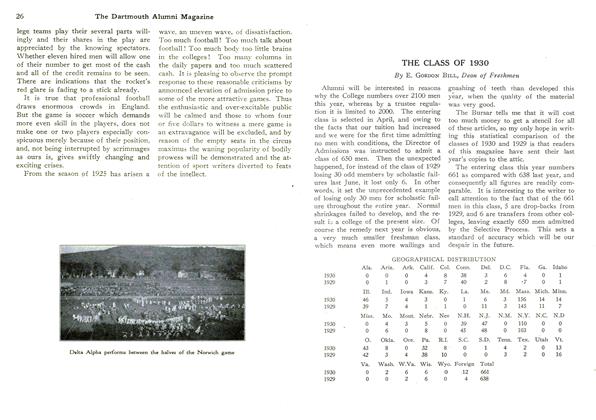

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

November 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1926 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1926 By Prof. Nathaniel G. -

Article

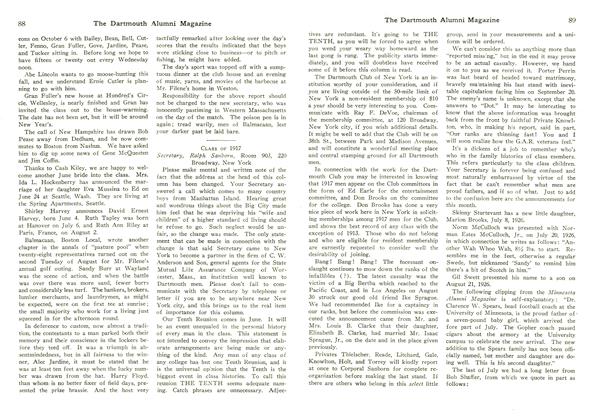

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1930

November 1926 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1926 By Ralph Sanborn -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1915

November 1926 By W. Dale Barker

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEDITORIALS COMMENT ON THE PRESIDENT'S OPENING ADDRESS

November, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLiberian Correspondent

June 1939 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Tom Braden '40

October 1942 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPress

December 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editorthe magazine has received a great many calls from alumni asking for an interpretation of the Cole affair.

APRIL 1988