By Luis Zalamea '42. Bogota-Mexico: Impresos Modernos, 1960.

Just four years ago we read Luis Zalamea's first volume of poetry, Requiem neoyorquino y otros poemas. In contrast to that cosmopolitan collection, his second volume is a single poem which focuses exclusively upon his native country, Colombia. Written in declamatory free verse, it invites one to penetrate the geographically various soul of an exotic land. The first of the five cantos, "Invocación," is precisely such an invitation, addressed to its readers imperatively in the second person plural. The next canto, "Cómo explicarte?," in the second person singular, is addressed to Colombia herself, interrogatively: How can I explain thee to those who know thee not?

The first two brief cantos thus form an introduction to the long central canto entitled "Trip without itinerary, from Cartagena to Gorgona." Cartagena is the Caribbean port, to the north; Gorgona is an island oil the Pacific coast of southern Colombia. In between we visit the Sinu River and Antioquia Province; we go up the savannahs over the frigid heights to Santa Fe, the colonial name for Bogota, the poet's birthplace, imagined as a port on the edge of a submarine landscape: nostalgia and renewal of childhood innocence. Then towns with Indian names, the Magdalena River, the plains and the jungle of La vorágine. The poet emphasizes the difficulty of communicating to us not only the strange landscape itself, but even more its subjective significance to him as an individual. The breathtaking heights of the Andes, the valley of the Cauca River, Cali, and Popayan lead us finally to the Pacific and the misty island which rises symbolically on the horizon. The long canto of this journey is certainly the heart of the poem; yet, as the poet realizes, even an atlas and a glossary are not enough help for the reader, who cannot really see and feel the strange places and animals and plants and foods unless he has already known them as a specifically Colombian Erlebnis. (Zalamea has demonstrated once again the geographically entrenched provincialism which so poignantly besets the isolated criollo cultures of Spanish America, which are almost as cut off from one another as they are from Europe and the United States.)

The two brief final cantos constitute a dual envoi. One is Zalamea's messianic appeal to his fellow Colombians, an optimistic annunciation of national rebirth and of the social realization of a poetic vision symbolized by the misty Pacific island. The other, "La presencia permanente," declares vindicated the poet's own spiritual fidelity, in all parts of the world and throughout his life, to childhood memories of Colombia. The poem as a whole is a resounding reaffirmation of faith, a faith rooted in a nostalgically remembered past and reaching out hopefully toward a Utopian future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

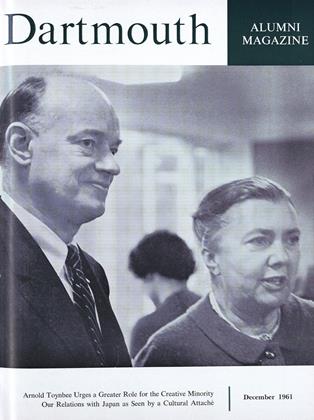

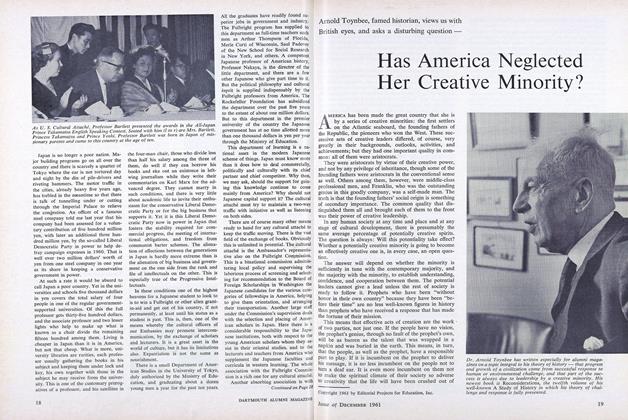

FeatureCULTURAL CATALYSIS

December 1961 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Feature

FeatureHas America Neglected Her Creative Minority?

December 1961 -

Feature

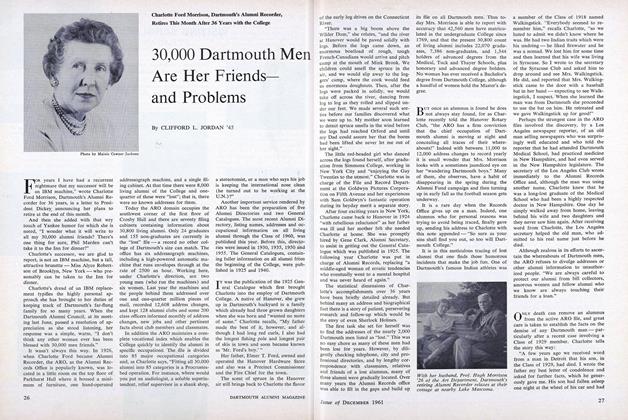

Feature30,000 Dartmouth Men Are Her Friendsand Problems

December 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

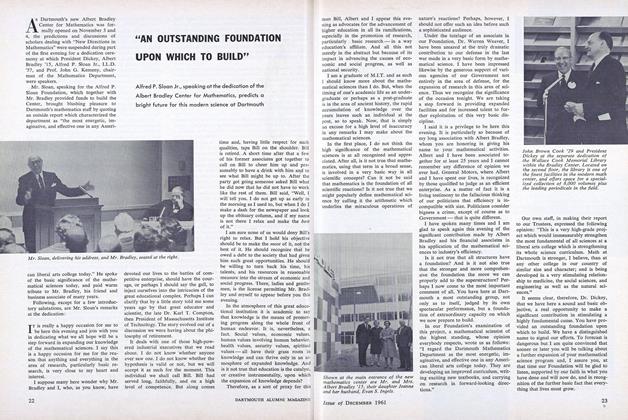

Feature"AN OUTSTANDING FOUNDATION UPON WHICH TO BUILD"

December 1961 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

December 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, JAMES L. FLYNN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1961 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HENRY S. EMBREE, JOHN F. RICH

ELIAS L. RIVERS

Books

-

Books

BooksGhost of Quixote

April 1980 By Frank F. Janney -

Books

BooksHUDSON BAY EXPRESS,

January 1943 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTOMORROW'S BUSINESS.

March 1945 By Malcolm Keir. -

Books

BooksTHE ILIAD OF HOMER

March 1952 By Philip Wheelright -

Books

BooksTHE COURT OF VIRTUE.

April 1962 By ROBERT G. HUNTER -

Books

BooksTHREE MASTERS

JUNE 1930 By Sidney Cox