On November Third Dartmouth College through E. K.Hall paid her tribute to Walter Camp of Yale. On thatday, the day of the Dartmouth-Yale game, there came toNew Haven the representatives of the leading colleges ofAmerica, all bearing some token of esteem for the man whoin life stood for the best and cleanest ideals in sport. Itwas more than 150 years ago that Yale sent out one of hersons to found a college in the wilderness and with that sonfour men who became the first graduates of DartmouthCollege. Therefore in this return of respect to Dartmouth'sAlma Mater and in this paying of a tribute to one of Yale'smost loved sons, it is more than fitting that the Dartmouthsentiment should be expressed by Mr. Hall, who was afriend and co-worker of Mr. Camp's in the field of sports,and occupies the same honored place in Dartmouth's lifethat Walter Camp occupied at Yale. The memorial gate-way to Walter Camp Field at Yale is not only a memorialgateway of interest to Yale men but to all college men inAmerica who love clean sport, and especially to those col-lege men who lent their aid in the building of the span.

THIS is an occasion entirely unique in the annals of college history. A great American university has named her playgrounds in honor of one of her distinguished sons. A noble memorial in the form of a massive gateway has been erected at the entrance to these grounds, carrying this man's name carved in great blocks of stone. The university has set this hour as the time for the dedication of this impressive struc- ture.

We expect to find here on such an occasion the life- long friends of Walter Camp—and they are here.

We expect to find here Yale men in great numbers— for this is Yale ground and Walter Camp was one of the Yale family—and the Yale family ties are strong.

But we also find here, in person and by proxy, repre- sentatives of schools and colleges from every part of this great country who have come to join with the men of Yale in the dedication of this memorial—so majestic in form and so unique in origin.

It must mean something when the colleges of Amer- ica request the privilege of participating with Yale men in erecting to the memory of a Yale man a monument on Yale soil.

It must mean something when Yale men cordially share their own exclusive right with the men of other colleges who also wish to honor the memory of this son of Yale.

It must mean something when 224 other colleges and universities and 279 preparatory and high schools, rep- resenting 45 states and including the far-off territory of Hawaii, together with the leading associations of football officials and of track coaches of the country, eagerly accept the opportunity thus graciously extended to them by Yale.

And what does it mean? I would like to answer that question and I undertake the answer with entire confidence.

All this did not happen merely because Walter Camp was in his generation the outstanding champion of athletic sports, nor because he was for 50 years the central figure in the greatest of all academic games—a game which he more than any other man developed and gave to the schools and colleges of the country.

Walter Camp gloried in the health, the strength, the speed, the skill, and the physical prowess that athletic sports develop; his heart sang with joy in the spirited clash of physical contest and combat; and the physical values which athletic sports produce so lavishly had no more eloquent and no more ardent advocate then he.

But it was not merely because of their physical values that Walter Camp devoted so much of his life to the development and advancement of athletic sports. He realized that these values pale almost into insignif- icance when compared with those greater values which come from athletic sports at their best—values not only of higher significance to the individual than physi- cal prowess or a healthy body but values which mould the character and determine the strength of our national civilization self-control self-reliance perspective —persistence—ability to co-operate—courage—forti- tude—honor.

He understood as few men have, the American boy. His ruling passion was to see him develop into a man's man. He realized long before most of us, and while many were still carping at them, that in the play- grounds and athletic fields of America lies the surest hope for conserving and perpetuating the virility of this virile race—increasingly surrounded and menaced by the seductive allurements of luxury and softness.

He saw the athletic field as a crucible where the youth of the land is tested and tempered under the in- tense heat of fierce competition and physical conflict. A crucible where the poisonous elements are driven off, and where other elements are changed into pure gold, and where entirely new values are fused into the boy's character—provided always that in the crucible there is present in abundant quantity the purifying re-agent of sportsmanship.

No man has done more for American sport than Walter Camp but his greatest contribution to sport is to the standards of sportsmanship. No man has done more to build up the Code which, if we preserve, will keep our sports clean and wholesome for all time and maintain these sports as one of the powerful sources of our nation's strength and our national character.

That is why this monument is here. That is why the schools and colleges of the country rejoice today in having shared the privilege of building this memorial.

You have some priceless traditions here at Yale—A true Yale man never quits. He never boasts in victory. He never whimpers in defeat. He plays the game to win. He gives it all he has but he plays it fairly. You are proud of those traditions and you have the right to be proud. What part Walter Camp had in building up those traditions you of Yale can answer better than I. But this I know—that no man has done more to im- plant, both by precept and by example, those same traditions in the schools and the other colleges of Amer- ica than the man whose name spans the gateway leading to Yale's athletic fields.

And that is the reason, Walter Camp, that I am here today. I come not primarily as your old friend to tell you what our life-long friendship means to me, but I come, fortified as you may see with eloquent creden- tials carved in stone, representing the boys of the schools and colleges of America, publicly to express for them their affection and their gratitude.

You dedicated your life to the American boy. The boys of America today join in dedicating this monu- ment to your memory in recognition of your service to them. You put romance, chivalry and idealism into their sports. As long as boys shall gather to play their games on lot, on playground or athletic field, may that idealism endure in all its beauty, its vigor and its virility.

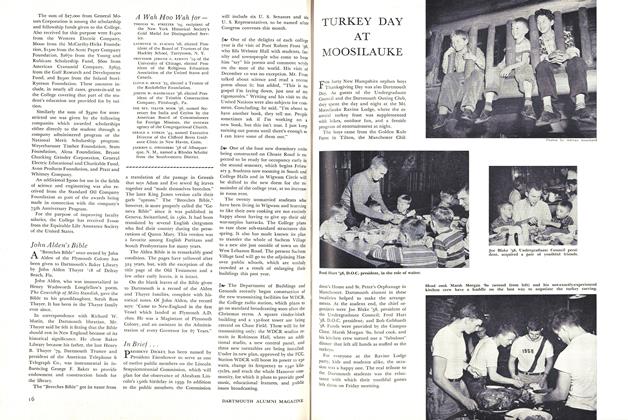

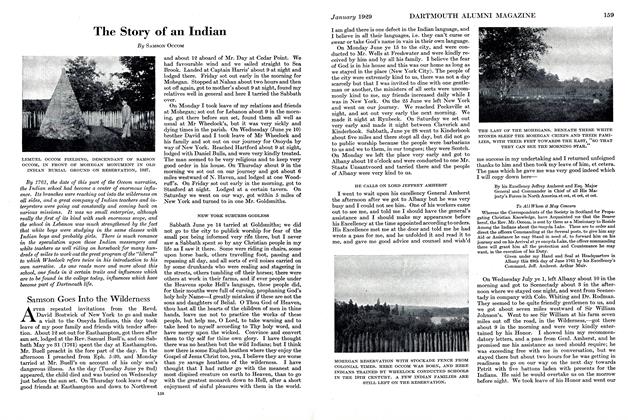

A SCENE FROM MOUNT MOOSILAUKE Looking east from the Beaver Brook Trail just below the Dartmouth Outing Club winter cabin on Moosilauke. The small trees—a few feet below timber-line—are encrusted with snow and frost-feathers, while about a foot of snow covers the foreground. The Franconia, Twin, and Presidential Ranges pile up in the distance. Mount Washington may be distinguished as the highest peak in the farthest range of mountains. (Picture taken Armistice Day, Nov. 11, 1928, by H. H. Leich '29)

*Address at the dedication of the Walter Camp Memorial, Yale University, Nov. 3, 1928.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

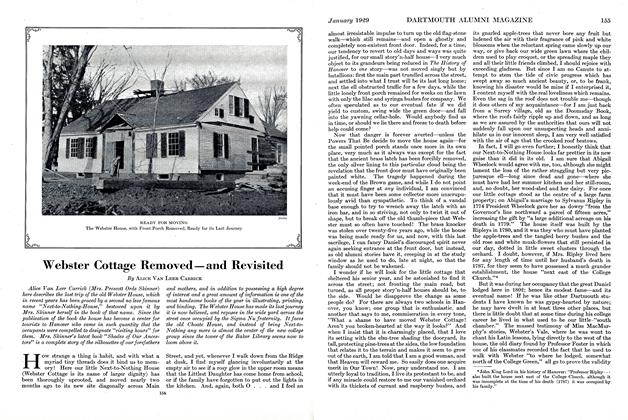

ArticleWebster Cottage Removed—and Revisited

January 1929 By Alice Van Leer Carrick -

Article

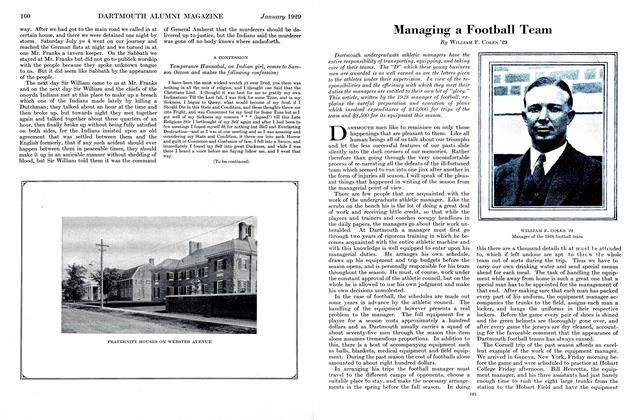

ArticleManaging a Football Team

January 1929 By William F. Coles '29 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

January 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1923

January 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1911

January 1929 By N. G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

January 1929 By Samson Occom