By William Kelley Wright, The Maemillan Company, New York, 1929.

Although written as a text for elementary courses, Professor Wright's latest work should appeal particularly to those whose good fortune it has been .to begin the study of Ethics under his direction. It is to them that the volume is dedicated, and they will find pleasantly familiar the breadth of interest and restraint of tone which characterize the work as a whole. Your reviewer is unqualified to hazard an opinion as to how well other texts have stood the test of class-room use. But, since this book succeeds admirably in its avowed purpose of presenting "a comprehensive view of the different fields of Ethics of most importance for the understanding of the moral outlook and problems of our time," we may safely suppose that it will enjoy wide use.

The introduction reminds the student of the importance of moral judgments and uses numerous current public issues as illustrations. Ethics is defined as "the scientific study of moral judgments." It is, however, immediately made clear that, although Ethics may be studied in an orderly fashion, the impossible is not to be attempted—moral values are not to be weighed and measured ac- cording to a technique pretending to mathematical accuracy. Ethics is shown to be dependent upon other branches of social study, such as Psychology, Economics, and Political Science, for conclusions as to the results of forces and institutions operating within their special purview. Moral judgments may then be formed concerning the worth of these results. Religion, however, should provide sanctions for those values which Ethics endorses.

Part I is devoted to Comparative Ethics. A sketch of the evolution of social organization, culminating in the free state whose citizens live together in the Relation of Citizenship, furnishes background for a description of the related evolution of moral judgments through the stages of Group and Custom .Morality to the rational search for valid judgments applicable to new situations—Reflective Morality. The moral development of the Ancient Hebrews, Ancient Greece and Rome, and Christianity is outlined in successive chapters, and the section concludes with a discussion of Modern Moral Development. Although these chapters are necessarily abbreviated, the treatment is generally sympathetic and is well calculated to arouse in the student a desire to become better acquainted with the ideas of the great leaders of moral philosophy. Because of their illustration of the inter-relation of social and moral evolution and because of their continuing influence, ancient Hebrew morals have been treated in some detail. To some the account may appear unduly expanded, while the inclusion of a multitude of parenthetical Old Testament citations supporting the statements of moral tradition constitutes a departure from the ruling practice of the book and seems of dubious value in an introductory text. The sections dealing with the influence of general social changes upon Greek moral thought and upon Christianity are especially vivid.

Part 11, Psychology and Ethics, opens with an examination of the primary impulses and their organization into sentiments. As society comes to regard some sentiments as praiseworthy and others as undesirable, virtues and vices are recognized. The cultivation of virtuous sentiments brings one "into harmonious and cooperative relationship with society." Courage, honor, temperance, justice, love, loyalty, economy, widsom, respect, and reverence are shown to be virtues in this sense. The "empirical me"—the concrete, composite self of every-day experience —is largely a product of the social environment and is influenced powerfully by sympathy and the desire to share the emotions of the particular groups to which the individual belongs. Desire for "pleasant feelings" constitutes an inadequate explanation of human conduct. Self Realization—the expression of one's entire personality—necessarily promotes social well-being and is a proper objective for individuals, who are seen to be psychologically free to mould their own selves and actions and who are, therefore, morally responsible.

Systematic Ethics is the subject of Part 111. Intuitionism is of limited usefulness; although the worth of certain human actions and motives may be determined by common sense or by conscience, simple moral axioms are not helpful in complicated situations. The treatment of Formalism, as represented by Kant, is particularly stimulating. The weaknesses of Formalism are viewed as its intuitive basis and its emphasis upon consistency with principle regardless of the consequences of the moral decision in question. Utilitarianism affords a fairly good guide to moral judgments and its contribution to moral progress has been great, but its psychological basis is not wholly satisfactory nor is it sufficiently concerned with the motives underlying men's actions. Eudaemonism, or Self Realization, affords standards which are necessarily somewhat indefinite. But it is accepted by Professor Wright because it recognizes the changing character of values and their corresponding virtues, takes into account consequences as well as motives, and concedes that the worth of values must finally be decided intuitively.

Part IV, Political and Social Ethics, includes chapters on The State, Distributive Justice, The Professions and Business, and The Family and the Position of Women. In the first of these chapters nationalism is seen to be capable of producing a useful patriotism; the possibility of its development into internationalism is viewed hopefully. Real freedom requires the enforcement of duties to the state and the performance of various public functions designed to reduce economic inequality. The strength and weaknesses of our legal institutions are thrown into sharp relief. The chief ethical basis for the punishment of crime is that it may promote general condemnation of the offense, but deterrence, prevention, and reformation are also important. War has promoted some desirable ends but at tremendous cost.

Distributive Justice necessitates the distribution of the national income in such a way as to afford individuals the maximum opportunity of achieving self-realization and to stimulate productive efficiency so that the national income may be as large as possible. Absolute equality in distribution is not advocated but, rather, a sharing of the product which will "enable and induce" individuals "to render the service which society has a right to expect of them." The possibility of conflict between distribution favorable to self-realization and conditions tending to promote productive efficiency might be more specifically developed. Capitalism (Competition) and various types of Collectivism are compared with reference to these standards and with conclusions generally favorable to existing economic arrangements, although the author discriminates carefully between competition as an ideal and the actual operation of the Competitive Process. He recognizes also the necessity of public intervention when competition is imperfect and points to the very considerable degree to which our present economic organization includes collectivistic elements.

The chapter on The Professions and Business indicates the nature of codes of professional ethics and the need for more specific commitments if they are to be of much value. In recent years there has been a marked improvement in business ethics, but one agrees easily with Professor Wright that there is still much to accomplish. In choosing vocations the students are admonished to serve society but to be sure of their fitness for the particular calling.

The study of the Family is approached through the history of marriage and the improved position of women. Monogamous marriage yields the richest of human satisfactions, although out of the relationship arise various responsibilities and problems. Continence is called for in preparation for marriage; trial marriages and divorce by mutual consent are regarded as destructive of a sense of responsibility. Divorce for cause, however, is defended and the increase in divorce in the United States is not as alarming as some would have it. A woman may choose to devote herself to the home or to an outside career, but there is no excuse for her lacking interests which will lead to self-realization.

Part V consists of a single chapter concerned with Metaphysics and Religion. The ethical postulates of basic intuitional judgment, the continuity of the ethical self, moral responsibility, denial of extreme optimism or pessimism, and the possibility of moral progress are briefly reviewed and related to the prominent schools of Metaphysics. The volume concludes with a summary of the relationship of Ethics to Religion. Religious ex- perience is regarded as an important moral force and the facts of terrestial evolution are seen as favorable to the concept of a personal God. The case for human immortality may seem less convincing.

Certainly a reading of the book as a whole cannot fail to impress upon one the fact that the liberal college, if it chose to require of all its students a study of Ethics as a conclusion to their formal education, might assist them to coordinate and interpret in terms of social welfare their departmentalized knowledge.

A list of carefully selected supplementary readings is appended to each chapter, those best suited to the beginning student being indicated. Some will approve the elimination of footnotes and the grouping of all the notes at the end of the book. Others, like the reviewer, may regret the fact that these notes, which are often genuinely illuminating in themselves and which usually refer to useful sources, are difficult to find. Searching them out is inconvenient and seems more damaging to continuity of thought than would be a glance toward the bottom of the page. With but a single exception, the publisher of books referred to in the notes is given only when it is The Macmillan Company, the publisher of the present volume. But it would be unfair to charge against the author the unfavorable impression of ethics in the publishing business which this practice creates.

OUR HARVARD FRIENDS ADVISE US Professors Murdock, Hillyer and Whitney of Harvard are compiling for the Harvard Cooperative Society each month books that they think will interest Harvard alumni. As the statement reads: "The committee will not attempt to pick out 'best sellers' or the 'best books of the month,' but will try to indicate some recent works which for one reason or another are likely to prove worth reading for customers of the Society. In the annual flood of new publications it is very easy for important works of non-fiction to escape attention; it is the hope of the Society to bring a few such works to the notice of Harvard alumni and undergraduates by presenting periodically .the titles chosen by Professors Murdock, Hillyer, and Whitney." The List: F. Ayscough Tu Fu, The Autobiography of a Chinese Poet. (Houghton Mifflin Cos.) P. Eipper, Animals Looking at You. (The Viking Press.) John L. Lowes, Of Reading Books. (Houghton Mifflin Cos.) Gilbert Murray, The Ordeal of this Generation. (Harper and Brothers.) L. W. Reese, A Victorian Village. (Farrar and Rinehart, Inc.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

December 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

December 1929 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meets in New York

December 1929 -

Article

ArticleCarnegie Report

December 1929 -

Article

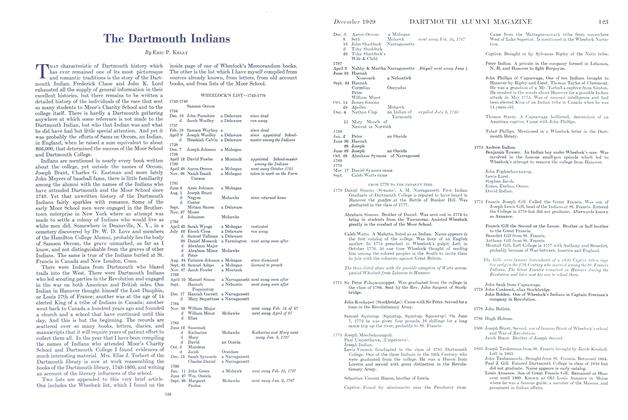

ArticleThe Dartmouth Indians

December 1929 By Eric P. Kelly -

Sports

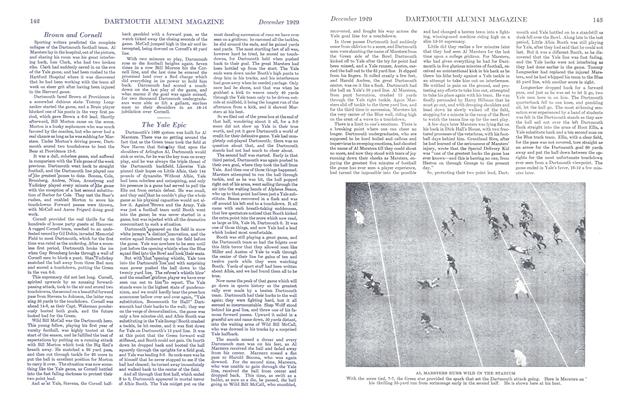

SportsThe Yale Epic

December 1929 By Phil Sherman

Nelson Lee Smith

Books

-

Books

BooksMemories and Anecdotes

January 1916 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

January 1953 -

BOOKS

BOOKSSomething Fishy

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 -

Books

BooksRights and Wrongs

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Charles M. Culver, M.D. -

Books

BooksFrom the Ground Up

APRIL • 1985 By Courtney C. Brown '26 -

Books

BooksMOUNTAIN CLIMBING GUIDE TO THE GRAND TETONS,

November 1947 By Henry Coulter '43, NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH