Dr. H. Meltzer and Professor E. M. Bailor are the joint authors of an article entitled "Sex Differences in Knowledge of Psychology Before and After the First Course," reprinted from the Journal of Applied Psychology for April, 1930.

THE PUBLIC CONTROL OF BUSINESS. By Dexter Merriam Keezer and Stacy May. Harper and Brothers, New York, $2.25.

The authors of "The Public Control of Business" have set for themselves a most important and an exceedingly difficult task. They view "antitrust law enforcement, commission regulation of enterprises affected with a public interest, and government participation in business 'as' three methods which seek to attain the same general end by different means." They propose "to put these three procedures in perspective and to find out in general terms where each stands as a part of a common program of control." Present tendencies toward an expansion of the field of public control emphasize the significance of such a study; the mere diversity of the methods utilized by public authority indicates the difficulty of satisfactory synthesis.

Messrs. Keezer and May further describe their book as "no substitute for . . . specialized studies" of various types, so one should not look for a closely detailed treatment of the problems of control in the different fields. Rather should one expect emphasis upon a coordination of the various controls presumably relating chiefly to their purposes , in spite of the denial of an attempt "to present such a broad, philosophical view of the relation of government to business as is embodied in Clark's 'Social Control of Business.' "

Following an introductory section, three chapters are devoted to the antitrust policy of the United States. Under the heading, "The Legislative Logic of Antitrust Law Enforcement," are described the provisions of, chiefly, the Sherman, Clayton, and Federal Trade Commission Acts. There follows a discussion of some of the more important judicial decisions interpreting these laws and defining the powers of the Federal Trade Commission, the Commission's difficulties in gathering information being particularly well handled.

The regulation of "public interest enterprises" (public utilities, banks, and insurance companies) is likewise treated in three chapters—the courts' views of their nature, the development of their regulation, and certain leading problems, including that of physical valuation. The chapter entitled "The Strange Case of Government Ownership and Operation" deals only with judicial decisions involving the well-established constitutionality of public participation in business enterprise; there is no discussion of the more controversial subject of its economic desirability. Conflicting federal and state regulatory jurisdiction is covered in the next chapter and we are reminded of the gaps which this conflict has created in the regulation of such important utilities as electric power companies and motor vehicle common carriers.

The conclusion stresses three general and continuing problems of regulatira, whatever its forms or methods: the collection of information, adequate jurisdiction, and competent administrative personnel. Present weaknesses along these lines are clearly shown. But there may be readers who, as they have progressed through the book, will have come to regard as a still more fundamental defect of the present situation our failure to define more sharply the aims and purposes of regulation and to harmonize more closely public control in a few fields with the outlines of the social order as a whole. Unless we turn our attention to this underlying question it may well be said, as Messrs. Keezer and May remark in another connection, that "the cart of regulation. . . .has been placed before the horse of adequate knowledge upon which regulation must be based if it is to be enlightened."

Although the descriptive sketches of the development of antitrust control and public interest regulation are useful, it seems to your reviewer that the promised synthesis is not provided in an altogether adequate fashion. Since the various types of public control involve so largely attempts to maintain competition or to provide regulation as a substitute for competition in more or less monopolistic fields, their composition might be facilitated through the use of some such coordinating agency as a brief contrast between the economic consequences of competition and the effects of unrestrained monopoly. This bit of background would be useful as a basis for agreement as to just what the public should attempt to accomplish through its control; in the absence of conclusions as to the objectives of public control mere activity in regulation might appear to be esteemed for its own sake. While our authors "disclaim a presumption of any mystical unity in the relation of these legal principles" (governing regulatory procedure), a concise statement of their economic philosophy would assist the reader in his solution of the complicated problems presented by unfair competition and public utility valuation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMy Love for Languages

August 1930 By Dr. James A.Spalding '66 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

August 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

August 1930 -

Article

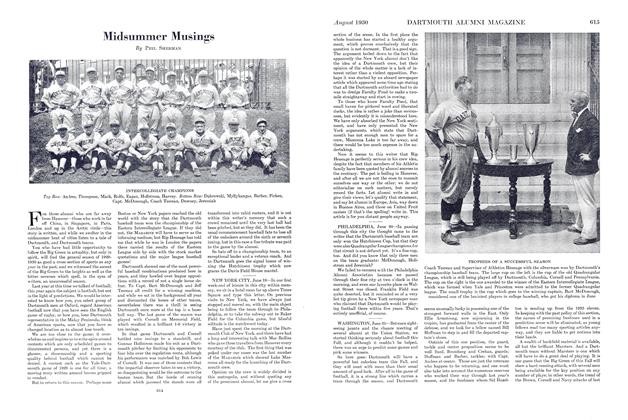

ArticleMidsummer Musings

August 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Article

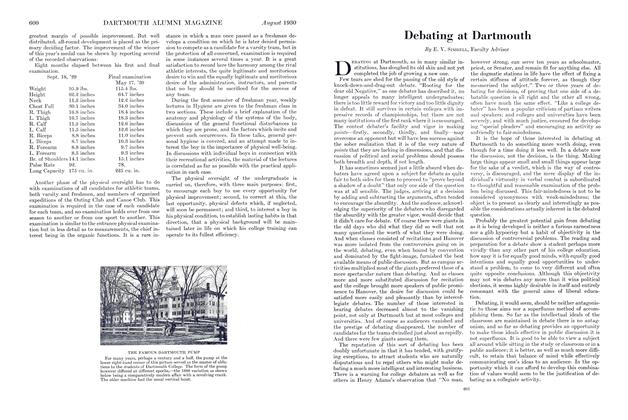

ArticleDebating at Dartmouth

August 1930 By E. V. Simrell, Faculty Advisor -

Article

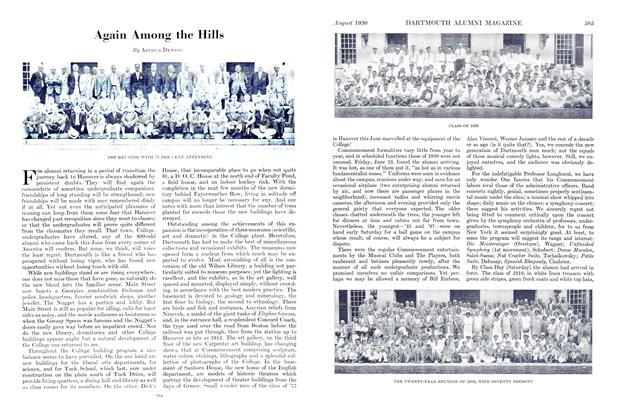

ArticleAgain Among the Hills

August 1930 By Arthur Dewing

Nelson Lee Smith

Books

-

Books

BooksRECENT RELIGIOUS LITERATURE

January, 1930 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Jan/Feb 2009 -

Books

BooksRAYMOND OF THE TIMES

October 1951 By Arthur M. Wilson -

Books

BooksWhen Life Begins

June 1962 By HE MILFORD (N. H.) CABINET -

Books

BooksSAMSON OCCOM

June 1936 By James Dow McCallum -

Books

BooksBANKERS' HANDBOOK OF BOND INVESTMENT

June 1939 By John W. Harriman.